HOMEPAGE

| CONTENTS

ISSUE 16 HOMEPAGE |

|

FIT TO BE TIED by Graham Andrews |

|

CLOSE-UP ON:GIDEON'S DAY/GIDEON OF SCOTLAND YARD, by J.J. Marric (John Creasey) |

|

|

These days, the reprint tie-in tends to be a perfunctory affair: stills/credits on front and back covers, with little evidence of input from the publisher's design team (if any). But there was a time . . . The ten-year period 1955 - 65 was particularly rich in imaginative tie-in cover artwork. Gold Medal (USA) and Panther (UK) brought out many volumes that transcended the lazy film-poster look. For the purposes of this article, however, I'd like to discuss the British and American promo editions of Gideon’s Day, by J.J. Marric (aka John Creasey). And several related matters. Gideon’s Day was first published by Hodder & Stoughton, London, and Harper, New York, in 1955. J.J. Marric was derived from (a) Creasey's own initial (b) the middle initial of his second wife, Evelyn Jean) and (c) the forenames of his sons Martin and Richard. I can only hint, here, at the fantastic career of John Creasey (1908 - 73): 500+ novels under 20+ pseudonyms, and over 60 million copies of his books have been sold worldwide. He created several long-running series, notably the Toff (58 titles), Inspector West (43 titles), Dr. Palfrey (31 titles), and - as Anthony Morton - the Baron (49 titles). Read all about it in John Creasey - Fact or Fiction? A Candid Commentary in Third Person, With a Bibliography by John Creasey and Robert E. Briney (Armchair Detective Press, White Bear Lake/Minnesota, 1968: revised edition, 1969). But it was Gideon (21 titles) that gave Creasey such a large measure of critical acclaim. He pioneered the British police procedural novel as we know it today (Wexford, Morse, Resnick, etc.), the year before Ed McBain's 87th Precinct did the same thing for American crime fiction. The late Julian Symons recognised this achievement in Bloody Murder/Mortal Consequences (1972, revised 1985): The portrait of Gideon is an attempt to show a fully rounded character, excellent up to a point but marred in the end by excessive hero-worship, and lack of humour. Apart from Gideon the strengths of the books are those of other Creasey work, an apparently inexhaustible flow of ideas and the ability to generate excitement in describing action (1974 Penquin edition, p. 210). Surprisingly enough, Creasey's work didn't hold much appeal for film-makers. The Honourable Richard Rollison appeared in two mediocre second features: Salute the Toff (1951, starring Tony Britton) and Hammer the Toff (1952, starring John Bentley). But Gideon’s Day was financed by a minor-major/major-minor Hollywood studio, Columbia, and directed by The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance - John Ford. From 1917, John Ford (1894* - 1973) directed some 50 features and umpteen short films. His best work includes: The Informer (1935), Stagecoach (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence (1962). “(Ford) developed his craft in the twenties, achieved dramatic force in the thirties, epic sweep in the forties, and symbolic evocation in the fifties" (Andrew Sarris, 1968). Recommended reading: John Baxter's The Cinema of John Ford (1971) and Tag Gallagher's John Ford: The Man and His Films (1986). By the mid-1950s, Ford's career was faltering because of illness and/or chronic alcoholism. He got fired from Mister Roberts (1955: completed by Mervyn LeRoy) for 'health reasons' - a ruptured gall bladder. But his punching out of the film's star, Henry Fonda, probably had something to do with it. For whatever reason, the three films he made after The Searchers hardly set the cinematic world on fire: The Wings of Eagles, The Rising of the Moon (both 1957), and The Last Hurrah (1958: the best of the bunch, from Edwin O'Connor's feisty political novel). Ford, however, was a maverick director who craved independence and didn't mind the occasional crying-into-his-Bushmills failure. Although commanding over 9250,000 per film, he made many 'home movies' for damn-all. For example: The Rising of the Moon, which got lost in its own Celtic twilight. But even mavericks are sometimes forced to come in from the cold. *Or 1895 (sources vary).

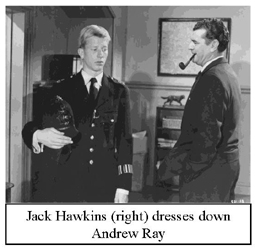

And yet Gideon’s Day wasn't just a 'quota quickie' (by Act of Parliament, renters/exhibitors are obliged to sell/show an acceptable proportion of British-made films). The production values belie the low negative cost ($543,000) and Ford did much more than point the camera. Thirty episodes and fifty speaking parts have been crammed into ninety-one minutes, without that if-it's-Tuesday-it-must-be Belgium look. The cast list reads like a veritable Who's Who of British/Irish character actors, headed by the stalwart Jack Hawkins (1910 - 73). Ford once described Hawkins as "the finest dramatic actor with whom I have worked." Take that, Henry Fonda. Again. Jack Hawkins made his first movie, Birds of Prey (American title: The Perfect Alibi), in 1930. Then came Hitchcock's 1932 remake of The Lodger, The Good Companions (1933), etc., etc. After Hitlerian War service, he perfected his stiff-upper-lippery in The Fallen Idol (1948), No Highway (1951), and, especially, The Cruel Sea (1955). Also the pukka Egyptian monarch in Land of the Pharoahs.

Hawkins might have been born to play George Gideon (nicknamed 'G.G.'). Physically, at any rate: In his big way, Gideon was distinguished-looking, with his iron-grey hair, that (hooked) nose, arched lips, a big, square chin. His looks would have been an asset in almost any profession from the law to politics, and especially in the Church; they occasionally helped to impress a jury, especially when there were several women on it" (Pan edition, p. 7). The film employs a limited voice-over narration. It opens with Gideon in full, irascible flow. Again, these scenes could have been lifted verbatim from Creasey's original prose: The wrath of Gideon was remarkable to see and a majestic thing to hear . . . as Gideon was a superintendent (later commander) at New Scotland Yard . . . it made many people uneasy . . . All the sins of omission and commission noticed by Gideon but not used in evidence against his subordinates, became vivid in the recollection of the offenders; on any one of these, Gideon might descend (ibid., P. 5). This time, the wrath of Gideon is being visited upon a corrupt detective-sergeant named Eric Foster -- changed to (Rip-Off?) Kirby for the film version. Foster/Kirby was played by Derek Bond (1919British leading man whose career never matched the chequered suit he wore in Nicholas Nickleby (1947). Forget P.C. 49 (American readers think T.J. Hooker): . . . you're a living disgrace to the C.I.D. and the Metropolitan Police generally. In all my years on the Force I've met some fools and a few knaves and here and there a rat, and you're one of the big rats . . . We make mistakes here at the Yard, and occasionally let a rogue in, but you're the first of your kind I've come across, and I'd like to break your neck" (ibid. P. 10). Inwardly, however, Gideon was "worried in case he had been swayed too much by his fury when handling Foster. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred he would have waited to cool off before tackling the man; this time he hadn't been able to. Every now and again he erupted as he had this morning into a rage which perhaps only he knew was virtually uncontrollable" (ibid., p. 17). In the film version, Gideon is decidedly more Dr. Jekyll than Mr. Hyde. T. E. B. Clarke (1907- ), the veteran scenarist (Passport to Pimlico, The Lavender Hill Mob, etc.) hews close to the plot/sub-plots. But he adds liberal doses of his own quirky humour. Gideon buys the wrong fish for his wife (aged haddock instead of fresh salmon), gets a parking ticket (which he won't fix, on general principle), rips his coat, is interrupted at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. When a sergeant snaps to attention, he remarks that the (Second World) War has been over for years. Ford set great store by family values - Walton, not Addams. He placed more emphasis upon Gideon's home life than Creasey ever did. As Kate Gideon, Anna Lee displays all the quiet heroism of a U.S. Cavalry wife at Fort Apache. Gideon is beaten to the bathroom by his flighty-but-respectful daughter, Sally (Pru, in the novel). She was played by Anna (daughter of Raymond, sister of Daniel) Massey, making her film debut. Ronnie and Jane Gideon were, in real life, Malcolm and Mavis Ranson. The nearest thing to a leading lady is Dianne Foster (Joanna Delafield). Other key roles were enacted by Cyril Cusack (Herbert 'Birdie' Sparrow), Ronald (son of Leslie) Howard (Paul Delafield), Laurence Naismith (Arthur Sayer), Jack Watling (Rev. Julian Small), and Donal Donnelly (Feeney*). *Murphy, in the novel. Feeney was Ford's birth surname (though sources vary …) Gideon knew that he loved London and after a fashion, loved Londoners. It wasn't just sentiment; he belonged to the hard pavements, the smell of petrol and oil, the rumble and the grow] of traffic and unending sound of footsteps, as some men belonged to the country . . . The country hadn't the same feel; he felt that it could cheat him, without him knowing it, whereas here in London the odds were always even (ibid., p. 19). Ditto the film version. Although Ford doesn't miss the usual touristy spots, he also hints at the London Town few Americans know. Tag Gallagher has claimed that: . . . Gideon’s Day is about London, the British, and 1957, about the claustrophobia, craziness, and complacent despair of modern life ("London Bridge is falling down . . ." mocks the theme tune) -- and it is surely not unintentional when we glimpse a headline about the H-Bomb (p. 359). For me, the only sour note is when an escaped convict from Up North is caught because some P.C. Plod spots him reading that day's Manchester Guardian (a national newspaper, even then). Gideon’s Day was filmed during the spring of 1957; released in March 1958 (U.K.) and february 1959 (USA.) Columbia titled it Gideon of Scotland Yard for the American market: (a) 'Scotland Yard' pushes certain commercial buttons and (b) audiences might have expect yet another Biblical epic. Jack Hawkins as the original Gideon? Hmm . . . The Pan (G-109) and Berkley (G-122) tie-in editions both came out in mid-1958, even though the Berkley (dated May) was off to a false start. Despite its scarlet backdrop, there is an air of solidity - even stolidity - about the Pan front cover. Artist S. R. Boldero was a Pan regular, with Eric Ambler's The Night-Comers (also 1958) and many other memorable paintings to his credit. "Behind the scenes at Scotland Yard" blares the blurb. Hawkins/Gideon stands off to stage right, gazing narrow-eyed at some unseen naughtiness. In the wider part of the cover, two unarmed Bobbies are approaching two shifty characters (with their hands obligingly up) outside what might be a gambling den. Pan Books were registered as a limited company in 1944 by co-owners Alan Bott and the Book Society. Post-war paper shortages led to only three titles being published during the next two years/Tales of the Supernatural (an uncredited anthology), A Sentimental Journey (Laurence Sterne), and The Suicide Club (Robert Louis Stevenson). But 1947 was a red-letter year, thanks to foreign printing facilities. The first three 'official' Pan titles were Ten Stories (Rudyard Kipling), Lost Horizon (James Hilton), and The Nutmeg Tree (Margery Sharp) - along with seven companion volumes. They soon built up an impressively varied list of authors, including P.G. Wodehouse, John Dickson Carr/Carter Dickson, Zane Grey, and Maza de la Roche. Unlike the then-staid Penquin Books (founded in 1935), Pan featured eye-catching pictorial covers. Many film tie-ins appeared in the 1950s, e.g. The Third Man & The Fallen Idol (a belated 1955) and The Sun Also Rises (1957).

One man's day at Scotland Yard!DOPE PEDDLING MAIL-VAN ROBBERY MURDER BURGLARY GANG VIOLENCE ARMED ROBBERY This is a new kind of thriller - a police 'documentary' based on real-life happenings. For sheer excitement it's top-class, and that's not surprising when you learn that 'J.J. Marric' is JOHN CREASEY, world-famous crime-writer. A line-drawing woodentop (slang for bell-helmeted constable) is shown doing sentry-go outside an equally indistinct Scotland Yard entry gate. And, in case somebody didn't pay close attention to the front cover: Now filmed as a/COLUMBIA BRITISH PRODUCTION/Directed by John Ford. Berkley goes to the opposite extreme with Gideon of Scotland Yard.Their front cover highlights these basic human psychological drives; violence, greed, and sex. Jack Hawkins hefts a Webley service revolver that might have seen action at the Siege of Sidney Street (1910). Greed is represented by an attaché case (banknotes? jewellery? letters of transit?) held by clinging brunette Dianne Foster. Big Ben (the clock-tower, not Cartwright senior) stands at phallic attention in the minimalist background. I'd like to credit the cover artist, but I can't make out the squiggly signature. Kennedy? Knight? Kinnock? Never mind. Well done, Squiggles. Berkley Books, Inc. had been founded in 1955 by Charles Byrne and Frederick Klein, formerly of Avon Books. The first volume was The Pleasures of the Jazz Age (edited by William Hodapp). George Simenon's Danger at Sea was another early title. They also reprinted mysteries, Westerns, 'historical' bodice rippers, and many sciencefiction anthologies by Groff Conklin and August Derleth. Gideon of Scotland Yard was one of the few film tie-ins published by Berkley, up to that time. Examples: Seven Men from Now (Burt Kennedy), 1956; Legend of the Lost (Bonnie Golightly), 1957; Escape from Colditz (P. R. Reid), 1958. Their back-cover blurb is much more robust than its True Brit counterpart, headed by a Dragnet-style timetable: CRIME AROUND THE CLOCK10: 30 a.m. Mail robbery . . . 12: 55 p.m. A rape murder . . . 2: 00 p.m. Store-keeper killed . . . 6: 00 p.m. Jewel robbery . . . 12: 01 a.m. Gunfight with bank robber . . . Here is one day in the exciting life of a Scotland Yard Inspector (sic). In the dramatic space of fifteen hours, he matches wits with hoodlums, dope pushers, rapists and murderers. You'll follow him through the twisted side-streets and alleys of London's crime-infested underworld. Phew! I’d hate to be Gideon on a bad day. A pink-tinted photograph shows Hawkins/Gideon grappling with an armed tea-leaf (Cockney rhyming slang for thief). And underneath that . . . you guessed it: The John Ford Production, starring Jack Hawkins and Dianne Foster, GIDEON OF SCOTLAND YARD, is a Columbia Pictures Release.

It must be said, however, that mid-1950s Berkley books are generally in the opposite condition to their Pan counterparts. Gideon of Scotland Yard is no exception, although it does have a certain scarcity value. Moe Wardle's 92.50 price tag, in The Movie Tie-In Book (Coralsville, Iowa, 1994), lies at least five times wide of the mark. But it must also be said that later Berkleys have proven to be much more sturdy. My favourite example: John Dickson Carr's Castle Skull (both April 1960 and August 1964 editions). Gideon’s Day: The Movie was a minor financial and critical success in the British home and Commonwealth markets. French cineastes also took the picture to their usually Anglophobic hearts: "The lightest, most direct, least fabricated film ever to emerge from one of Her Majesty's studios" (Cahiers du Cinéma). And it fared even better in mystery-mad West Germany. In the USA, however, Gideon of Scotland Yard was not so much released by Columbia as half-killed trying to escape. They consigned it to the 'arty' cinemas showing dangerously 'foreign' films that could then be found in places like Greenwich Village (and probably still can). Much later (1983), Disney gave a similar brush-off to their under-rated version of Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes. Gideon of Scotland Yard suffered a 950,000 loss in first-year domestic gross. Self-fulfilling prophecy, huh? But its popular and critical reputations have grown over the passing time. Steven H. Scheuer's Movies on TV and Videocassette awards it three stars (Good) out of a possible four (Excellent). Not so with Leonard Maltin: ("91m. *½ . . . Hawkins is likeable but the film is unbelievably dull . . . British version, titled GIDEON’S DAY, runs 118m. Originally released in the U.S. in black and white" (Movie & Video Guide). You pays your money . . . There was no call for a sequel. The vital box-office numbers just didn't add up. John Ford's directorial career became ever more scrappy after Liberty Valence and the rumbustious Donovan's Reef (1963). He made Cheyenne Autumn (1964), which featured those hitherto closet Native Americans Sal Mineo, Ricardo Montalban, Gilbert Roland, and Victor Jory. Young Cassidy (1965) was a perceptive biopic of Irish playwright Sean O'Casey, but it was almost wholly directed by Jack Cardiff Jack Hawkins consolidated his international stardom with Ben-Hur (1959), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and Zulu (1963). He headed up the Four Just Men (1959), a British TV series co-starring Richard Conte, Dan Dailey, and Vittorio de Sica. But, in 1966, throat cancer led to the removal of his vocal chords. Subsequent films (Shalako, Young Winston, etc.) were dubbed by either Charles Gray or Robert Rietty. With real heroism, Hawkins finished the autobiographical Anything

for a Quiet Life (Elm Tree Books/Hamish Hamilton, London, 1973)

just weeks before his death. Even the title had a beat-the-Devil ring

to it. He “(Ford) was a perfect actor's director. He refused to work if any of the management were present. This was a cunning ploy, because when a film is halted the delay costs a great deal of money, and this fact acted as a deterrent to uninvited visitors. At first meeting, Ford's appearance could be a trifle alarming. He wore a black patch over one eye and a greasy, battered trilby. I was told that the patch and the hat had been with him for at least fifty years. There were also odd little bursts of inexplicable eccentricity that one had to accept . . . Although, in the past, Ford had the reputation of being a fairly heavy drinker, at the time of making this film he was on the wagon, and fairly virulent about people who did drink . . . "I shan't want you until this afternoon," he announced. "Go and have some lunch." I said: "Thank you," and was just about to leave the set when he asked: "Where are you going?" There was a silence when I replied: "To a pub across the road." "Are you going to drink?" "Yes. " "What are you going to have?" "A gin and tonic, I should think." "In that case," he said, "have one for me." When I got back, John was sitting in his director's chair. "How was lunch?" he asked. "Fine," I said. "Fine.” "And how was the drink?" "Very nice." "You put too much tonic in mine." This patter became a kind of daily running gag. Sometimes he would slightly vary it by saying: "I think I feel like a couple, today." I liked working with him, and he knew his business backwards. When John Ford said a take was good, you knew it was.” Meanwhile, John Creasey just kept churning out novel after far too many novels. I recently bought a 1962 Corgi edition of The Black Spiders (a Department Z story, first published in 1957). It was clean, had a pleasant cover, and cost me fifteen Belgian francs, i.e. next to nothing. Pity about the words on pages 7-158. If only he'd written less Toff/Department Z novels and spent more time on Gideon/Inspector West. Julian Symons, continued: The weaknesses (of Gideon) are again characteristic, lack of the imagination necessary to vary a formula once it has been established . . . and a level of writing that at its best is no more than flatly realistic. The first Gideon books were pioneering works in the form of the police novel, and they promised more than Marric was able to perform (ibid.) The Gideon books might seem to be tame stuff today: "We are not living in the age of Dixon of Dock Green,* where a villain immediately says when faced with a police officer, "It's a fair cop, guv" (Lord *British TV series (1953 - 76), starring Jack Warner as the eponymous East End copper, who had been summarily killed off by 'young tearaway' Dirk Bogarde in The Blue Lamp (1950). Richard Widmark's Madigan is, I suppose, the nearest American equivalent. Annan: quoted in The Observer, 14th February 1993). But they can still evoke those simpler years of pure Manichean struggle between capital-lettered Good and Evil. The Sunday Times was in no apparent ethical dilemma about Gideon's Month (1958): "Authentic, well told and exciting." Gideon's River (1968) - Old Father Thames, of course - is arguably the best late entry. Marric then served a Wimbledon ace in Gideon's Sport (1970). Creasey adapted Gideon's Week (1956) for the stage, as Gideon's Fear (produced in Salisbury, 1960: published by Evans, London, 1967). He also wrote several Gideon short stories, e.g. 'Gideon and the Pigeon' (Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, February 1971). After Creasey's death, William Vivian Butler wrote two further novels: Gideon's Force (1978) and Gideon's Law (1981). Gideon's Way came to British TV screens in 1964 (26 x 50m black and white episodes). American viewers knew it as Gideon, C.I.D. Jack Hawkins being unavailable, Gideon was played by the tough-but-cuddly John Gregson (1919 - 75). "Standard cop show, efficient in all departments" (Halliwell's Television Companion). Hodder Books (H & S' paperback imprint) brought out some tasteful tie-in editions, with a passport' photograph of Gregson on each front cover. Ditto The Baron, in 1965 (30 x 50m colour episodes), personified by the wooden Steve Forrest (1924 - ). "Routinely glossy adventures, pleasingly implausible plots, mid-Atlantic atmosphere, vaguely based on the John Creasey character" (ibid.) No illustrated tie-ins, to my uncertain knowledge. Apart from Gideon's Way, John Gregson - of Whisky Galore and Genevieve movie fame - had a spotty TV career. He ended up playing Shirley Maclaine's photo-editor boss in Shirley's World (1971). "Unpleasing comedy drama series with a star ill-at-ease" (ibid.) Ditto the co-star. Berkley continued to paperback Gideon novels in the USA., late joined by Pyramid and Popular Library. But they never went mad on film/TV tie-ins, except for The Avengers (1967 - 68): The Afrit Affair, The Drowned Queen, The Gold Bomb (Keith Laumer); The Magnetic Man, Moon Express (Norman Daniels); The Floating Game, The Laugh Was On Lazarus, The Passing of Gloria Munday, Heil Harris! (John Garforth). In the UK, Pan reprinted the early Gideons until H & S got their paper-backing act together. But they soon rode the lucrative James Bond film wave, from Dr. No (1963) to The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). The indefatigable John Burke (1922 - ) has written many original Pan novelisations, e.g. Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965) and a rewrite of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). The New York Times and the London Sunday Times ably summed up Gideon in general; Gideon’s Day in particular: (a) "The finest of all Scotland Yard series"; (b) ". . . factual and unpretentious, this obviously knowledgeable account holds the reader more securely than any stereotyped thriller." They might just as well have been writing about John Ford's too-long neglected film version - or even the TV series. But the last line must come from Creasey/Marric/Gideon. From Gideon’s Day (or any other book in the series, really): "The hell of it was that this was just another day." J.J. MARRIC BIBLIOGRAPHYU.K. publishers: Hodder and Stoughton. U.S. publishers: Harper. Gideon's Day (1955). As Gideon of Scotland Yard, Berkley, 1958. Gideon's Week (1956). As Seven Days to Death, Pyramid, 1958). Stage version: Gideon's Fear, Evans, 1967. Gideon's Night (1957). Gideon's Month (1958). Gideon's Staff (1959). Gideon's Risk (1960). Gideon's Fire (1961). Gideon's March (1962). Gideon's Ride (1963). Gideon's Vote (1964). Gideon's Lot (1964). First edition: Harper. H & S: 1965. Gideon's Badge (1966). Gideon's Wrath (1967). Gideon's River (1968). Gideon's Power (1969). Gideon's Sport (1970). Gideon's Art (1971). Gideon's Men (1972). Gideon's Press (1973). Gideon's Fog (1974). First edition: Harper. H & S: 1975. Gideon's Drive (1975). By William Vivian Butler: Gideon's Force (1978); Gideon's Law (1981). |