The

thing that stands out about Jack

O'Connell is his sheer enthusiasm for the art and craft of writing. He

was in London

for a

brief visit, and an on-stage interview with Maxim Jakubowski, in

between

festivals in France,

where his books are popular, and Dublin,

which, as an Irish-American, he was thrilled to be visiting for the

first time.

As we reduced the world's stock of Guinness, and a bitter named The

Fall, with

impressive Biblical overtones, in an Irish pub nestled in a West

End

alley, O'Connell spun

out the pleasures of reading which, for him, grew into the pleasures of

writing. That we appeared to share the same tastes, indeed many of the

same

experiences with the same editions of the same paperbacks of our

younger days

meant the two hours became an exercise of head-shaking agreement, each

punctuated by another drink.

O'Connell

was born, educated, and

has spent his whole life in Worcester, Massachusetts ('within a

three-mile

radius, really'), which provides the geographical basis of his

fictional Quinsigamond,

but it is his reading that has provided Quinsigamond with its unique

mix of

rust-belt America, Weimar Germany, and futuristic LA. Although it's

easy to see

the influence of any number of modern cult-favourite writers in

O'Connell's

work, it is sui generis, never derivative, and at least two of his five

novels,

his first Box Nine, and his latest, The

Resurrectionist, deserve to stand alongside names like

Pynchon, DeLillo,

Disch, Dick, or and Burroughs.

Like

many cult writers, though,

none of O'Connell's books has found commercial success to match their

critical

acclaim. His problems may have started when Box

Nine, won the Mysterious Press first novel award. Prestigious

as the prize

was (and appreciated as the $50,000 prize was as well), it saw him

labeled as a

'crime writer', and although it fit into that category, it also

resisted it.

Genre labels don't quite work for O'Connell; there are significant

elements of

sf, and stylistic experiment which put much 'serious' fiction to shame,

which

makes it difficult for them to appeal to the 'hard core' crime reader,

while at

the same time making it almost impossible to reach beyond the genre

boundaries

created by the 'mystery' section of bookstore shelving.

Along

those lines, I noticed Jack

was carrying the new US

paperback edition of The

Resurrectionist, and I commented that the covers of that book

reflected his

dilemma of classification. Constant nodding in agreement and digressing

into

tangential concerns that seemed to be mutually apparent immediately....

JOC:

I loved that first cover (the US

cloth

edition), but the publisher thought it was not quite right.

MC:

It emphasized the circus/freak

show sub-plot; it reminded me of Glenn David Gold, or maybe a book like

The Prestige or The

Illusionist.

JOC:

And this cover (which features

cards) is along the same lines, but less mysterious. I think it

reflects part

of the problem with my books. I was doing a tour recently, and in Denver

I was

in the general fiction section, in Phoenix

I was

in crime, and in San

Francisco

I was in horror/sf...

MC:

Which might tell you more about San

Francisco

than

your books! But the British edition really looks great, like a

mainstream

novel, perhaps historical, that John Banville or someone might have

written.

Maybe we should call it 'slipstream'...

JOC:

No Exit have done a great job with

my covers...

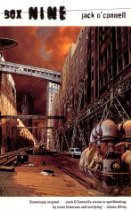

MC:...and

they've always GOT

the book; the Box Nine cover is

much more sf than

anything else! I saw you mentioned Harlan Ellison as an early

influence. I

didn't see Ellison the writer as much as Ellison the editor, because

everything

you've written would fit nicely into Dangerous Visions.....

JOC:

Oh yeah. I loved those books,

Disch, Delany, Aldiss. I sort of stumbled into sf as a kid, but then

this stuff

seemed so radical, and those writers led me, naturally, to finding Gravity's Rainbow, and wow! There's an

anthology of stories out now, called The

Secret History of Science Fiction, and it's based on a piece

Jonathan

Lethem wrote about ten years ago, speculating on what would have

happened if

the Science Fiction Writers had voted the Nebula to Gravity's

Rainbow in 1973, when it was nominated, instead of Arthur

Clarke's Rendezvous With Rama. From Pynchon to Delany's Dhalgren was a

natural

step.

MC:

And where does the crime fiction

fit in?

JOC:

As a kid I loved Hammett and Chandler,

and

the next generation of pulp writers, the Jim Thompsons and David

Goodises. But

my first fictions were two Pynchon-type novels, long and dense, and

they never

sold. Then I did Box Nine, which is

at heart a dark city noir, and has a female detective, and after it

sold the

first question was, can you make it a series? Is the main character

coming

back? And I said 'sure', because in my mind the main character was the

city,

Quinsigamond, not the woman! Both my agent and the editors were

disappointed,

but I said, did you see where Leonore winds up at the end of the book?

And they

said, well, send her to rehab! From a strictly commercial point of view

they

were, as usual, righter than I was. I think the problem is that I'm

generally a

little too dense for the dedicated crime reader, and there's no way to

make the

jump to 'literary'. There have been some relatively brief windows into

what

they call the 'slipstream', the cultish books just off the mainstream,

but now my

attitude is I've written five books, I'm turning 50, and I'm just gonna

write

what I write. You never know what's going to come out...

MC:

The Resurrectionist is your first

book in nearly a decade. Was it

very carefully planned?

JOC

(laughing): Just the opposite!

Partly, I was working days, editing the alumni magazine at Holy Cross,

and I'd

get up at four

am

to write. But the first draft did not contain Limbo

((the comic book story which Sweeney reads to his comatose son)) and I

wrote it

in a white heat, in about 8 months, which all began after a cafe crawl

around

Poitiers, at a festival with Francois Guerif, or Rivage, my French

publisher.

It was inspired by the Gold Medal guys I love, particularly Gil Brewer,

and it

was the story of Sweeney and his son and the gang of bikers. I'd

written maybe

90% of it, and I was really excited and I sat down to write a simple

scene,

where Sweeney reads a comic to his son, and the questions started. I

took a

left turn. Six months later, the wife says 'how did it go?' and I say

'we're

going to have to get rid of Sweeney,' and she looks at me and says

'Let's not

do that, alright?'. But the Limbo story just grew and grew, and in the

end it

was double the length it is now in the book, as I had to select just

the best

bits.

MC:

How direct is the Gil Brewer

influence?

JOC:

It's partly conscious and partly

organic evolution. I knew from the beginning that the only thing I

wanted to do

was write, but I had this terror because it didn't seem a career option

to a

kid growing up in Worcester!

But it was the verve of those guys, the Brewers, and Ellisons,

and also Richard Matheson, which I wanted to emulate. Eventually, I was

able to

marry it to more metaphysical themes, and more epic scope, but it took

lots of

experimentation, false starts, and frustration; not least those two

novels

which are up in the attic somewhere. Box

Nine finally started to do it, I think by leaning more toward

the genre

electricity side of things.

MC:

The crime element of The Resurrectionist

is mainly one of character;

Sweeney is a real noir hero, he's disturbed, he's needy, and above all

he's

vulnerable, with a weak spot that the ruthless can take advantage of,

and

there's a black widow femme fatal, in Nadia, a seemingly virginal

blonde in

Alice and a creepy shrink, a Dr. Ampthor type, in her father...

JOC:

That's exactly on the money -- in

fact, when I was in Dunkerque, on my French tour, I gave a little Cliff

Notes

version of the difference between the hardboiled first generation

writers like

Hammett and Chandler and the noir second generation of Thompson and

Goodis and

as I described the shattered protagonist ripe for total destabilization

by the

object of desire, my mind flashed on Sweeney.

MC:

The book cries out for adaptation

too. The Limbo Comics, I'm amazed someone doesn't jump at adapting them

as

comics, it's very much like Alan Moore..

JOC:

And how great would that be!? Comics, and then the movies!

MC: I'll drink to that.

|