|

|

|

|

|

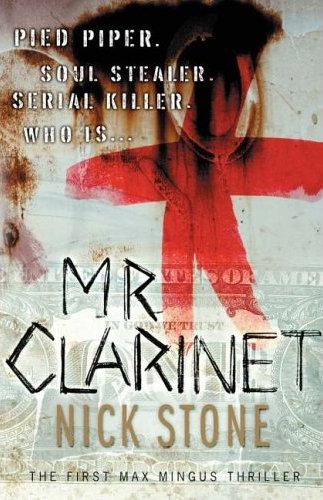

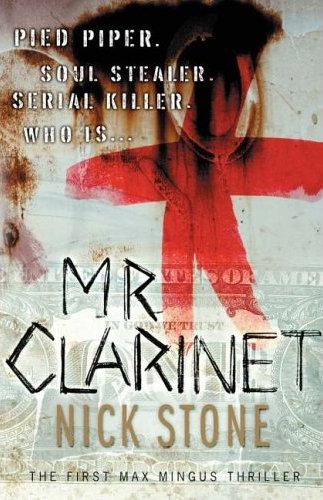

I had a real treat this January because my dear friend, the award winning writer Ken Bruen [www.kenbruen.com], tipped me off about a debut novel that blew his socks off.

It was at the launch of his latest Jack Taylor thriller Priest:- http://archive.shotsmag.co.uk/photoshoots_2006/ken_bruen/ken_bruen.html Ken and I got talking about Mr Clarinet by the enigmatic Nick Stone - a book that at the time was new to me. I got the book the following day; read it in one sitting and suffered nightmares for weeks after. I had to put my thoughts down on paper about this terrifying novel both for the American January Magazine as well as for Shots eZine:- http://www.januarymagazine.com/crfiction/mrclarinet.html. I interviewed Nick for Shots to learn more about him:- http://archive.shotsmag.co.uk/interviews2006/n_stone/n_stone.html In July I was in the US with Stav [The Devil’s Playground] Sherez when we heard that Nick Stone’s debut had won the CWA Ian Fleming Steel Dagger Award – that was a good excuse to buy a great bottle of wine to toast his success. So with Mr Clarinet out now in paperback in the UK, and out in the USA in hardback in May in 2007 – I thought I’d ask Nick Stone to tell us how he came to write this remarkable novel. Oh, if you haven’t read this amazing debut thriller, grab a copy fast and find out what all the fuss is about. But be afraid, be very afraid.

I Y Smith & Wesson Nick Stone

The plot for my debut novel, Mr Clarinet didn’t come to me all at once. I got it in two instalments. The first came to me in Haiti in December 1995, where I was visiting my family for the holidays. At the time, I hadn’t seen most of them nor set foot in the country for thirteen years.

I remember the moment lightning struck. It was midday – bright and baking. I was pacing around the courtyard with my late grandfather’s Model 10 Smith & Wesson revolver. I was having a nostalgic moment.

We went back, the gun, the courtyard and me. My first memory – age three – is of playing in the courtyard; my second is of the dog that approached me moments later. It was a stray black German Shepherd. It didn’t snarl or growl or even bark. It didn’t run up to me and pounce. It simply strolled into my life and – my third memory - clamped its jaws around my forearm and pulled me off my feet.

What happened next is a blank, although I’ve long since had the empty spaces filled in for me by people who weren’t there. My grandfather was sitting nearby in the shade, watching over me. This was something he liked to do while he still could. He was dying of cancer and knew he didn’t have long to go.

He shot the dog with the pistol he always kept at his side in case of thieves. Two weeks later he died in his sleep.

My uncle Jean inherited the pistol. He mounted it in a glass case and used to pass it around at dinner parties, whenever the conversation went stale. I found the gun quite by accident, still sitting in its display case, on top of a cupboard in the house I was staying in.

Jean told me the weapon’s history and then took it out of the case and handed it to me. It had a dull grey finish and a wooden grip which had turned almost black with time. It was heavier and sturdier than it looked.

The day I took the pistol for a walk in the courtyard – all the while mentally recreating the scene where my grandfather had saved my life – I noticed something about it I hadn’t initially seen, something only the intense sunlight revealed. On one side of the grip, close to the end, three thin straight lines, each about a centimetre long, had been crudely scored into the wood. I guessed what they stood for.

I wondered how my grandfather had felt, being God three times over, for a split second each. I wondered how he’d lived with himself afterwards. And that was how and when I got the first idea for my novel.

Simple, really: I’d create a character who’d killed three people. I’d give him bad dreams and a mounting sense of remorse. I’d make him sorry.

*

Haiti, in case you don’t know, is a Caribbean island, situated roughly between Cuba and Jamaica. It shares a border with the Dominican Republic. You can’t miss it when you fly over it. It’s the colour of rust on rust. Its neighbours are all lush and green, healthy and abundant. Haiti looks like it doesn’t belong there, like it’s floated in from another, sorrier part of the world, a place where it barely rains and nothing ever grows or lasts.

Haiti is apart, unique and alone, as are its people. They’re also exceptionally funny: two hundred plus years of living with almost constant natural and man-made disasters means there’s gallows humour in the DNA.

I returned to live and work there in September 1996. I’d got a marketing job in a now defunct local bank, based in the capital, Port-Au-Prince. I stayed until December 1997.

The place was a disaster zone. Think of some war/famine/drought ravaged African landscape teeming with extreme poverty and disease and you’ll get a picture of what it was like.

You couldn’t – and still can’t – drink the tap water in Haiti. It’s so filthy you’re urged to keep your mouth shut when you’re having a shower. The electricity supply is temperamental. Power cuts can last for days. Everyone who can afford one has a generator. Everyone else lives by candlelight or in complete darkness. There are precious few streetlights in Haiti. It’s not only the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, it’s also the darkest.

A little publicized consequence of the 1994 US military invasion of Haiti was the repatriation of most Haitian criminals from American prisons – hundreds of murderers, rapists, gang members, and drug dealers were flown back to the island and handed over to the country’s authorities. There was a slight problem with this – actually, make that a rather large problem: at that moment in time, Haiti was quite literally a lawless land. Not only was the country without a police force or army (both having been disbanded by order of the UN), all of its prisons had been emptied of convicts and turned into squats, the judiciary had been suspended and all laws annulled pending the drafting of a new constitution. The Haitian “authorities” who took possession of the homecoming convicts were actually nervous airport security staff. They escorted the criminals off the runway and released them. The criminals found their way to Port-Au-Prince and its neighbouring slum, a vast congealed cesspool and home to half a million people, called Cité Soleil. Within months they were running both.

The crime rate rocketed on the island: murders, home invasions, car-jackings, rapes, drug trafficking and, very disturbingly, a whole new dark phenomenon – child kidnapping.

Children had always gone missing in Haiti. Most of them had disappeared for good, never to be seen nor heard from again. There were rumours of adoption rackets, black magic ceremonies, child labour and other things I won’t go into here, but kidnapping was a whole new ball game. And for once it wasn’t the poor who were suffering the worst, but the rich. After all, only they could afford to pay the ransoms.

When I heard about this I got the rest of the idea for my book. I’d send my triple murderer to Haiti to look for a missing child. I’d make him a private detective. He’d be haunted by his past - the life he’d lived, the lives he’d taken and the consequences he’d reaped. His name would be Max Mingus, after an old school friend who’d got me reading Kafka, and one of my heroes, the very great Charles Mingus: jazz bassist extraordinaire, band leader, composer, bully, brawler, genius and author of Under the Underdog – the quintessential jazz autobiography, written as lopsided noir.

Now you know.

© 2007 Nick Stone |

| Webmaster: Tony 'Grog' Roberts [Contact] |