|

|

|

|

|

|

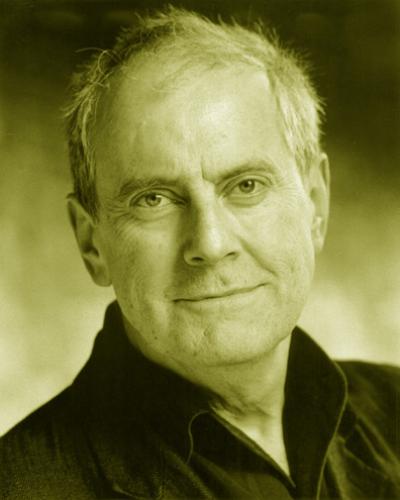

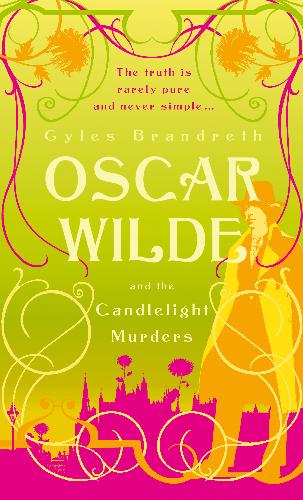

W riter, broadcaster, former MP and government whip, Gyles Brandreth , makes his first foray into detective fiction with OSCAR WILDE AND THE CANDLELIGHT MURDERS , published by John Murray on 10 May 2007. The novel is the first in a series of Victorian murder mysteries by Brandreth , each of them featuring Oscar Wilde as the detective.

How did it come about? Gyles Brandreth explains:

How did it come about? It’s a long story, so I will try to keep it short.

Since I was a boy, I have been an avid admirer of both the works of Oscar Wilde and the adventures of Sherlock Holmes. (At school, my best friend was the actor, Simon Cadell. He starred in my school production of A Study in Sherlock. Jeremy Brett was brilliant as Holmes, I grant you. But for me, Simon, aged twelve, was definitive!)

Anyway . . . about ten years ago, in the late 1990s, by chance, I picked up a copy of Memories and Adventures, the autobiography of Arthur Conan Doyle, published by John Murray in 1924, and discovered, on page 94, that Arthur Conan Doyle and Oscar Wilde were friends. I was amazed. It would be hard to imagine an odder couple.

They met in 1889, at the newly-built Langham Hotel in Portland Place. They were brought together by an American publisher, J M Stoddart, who happened to be in London commissioning material for Lippincott’s Magazine. Evidently, Oscar, then 35, was on song that night and Conan Doyle, 30, was impressed – and charmed. The upshot of the evening was that Mr Stoddart got to publish both Arthur Conan Doyle’s second Sherlock Holmes story, The Sign of Four, and Oscar Wilde’s novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and I was inspired to write the first of ‘The Oscar Wilde Murder Mysteries’.

My story begins on the afternoon of the day of Wilde and Conan Doyle’s first encounter. Oscar calls on a house in Cowley Street, Westminster, expecting to meet up with a friend – a female friend, as it happens, a young actress . . . Instead, in a darkened upstairs room, fragrant with incense, he discovers the naked body of a boy of sixteen, his throat cut from ear to ear.

Wilde, established poet and wit, ‘the champion of aestheticism’, (and happily married to Constance and living in Tite Street, Chelsea, with their two sons), turns to Conan Doyle, doctor and writer of detective fiction, ‘the coming man’ (still practising as a general practitioner in Southsea), for help - but Conan Doyle quickly discovers that when it comes to the art and craft of amateur sleuthing Oscar Wilde has very little to learn from Sherlock Holmes. Wilde is overweight and apparently indolent (more Mycroft than Sherlock Holmes), but his mind is amazing: his intellect is as sharp as his wit. Oscar Wilde, in his own way, is as brilliant as Sherlock Holmes - and just as Holmes had his weakness for cocaine, Wilde has his weaknesses, too.

Famously, Wilde was a brilliant conversationalist. He was, also, by every account, a careful listener and an acute observer. And he had a poet’s eye. He observed: he listened: he reflected: and then – with his extraordinary gifts of imagination and intellect – he saw the truth . . . What makes Wilde particularly attractive as a character to write about is that he was such a fascinating and engaging human being. What makes him particularly useful – and credible – as a Victorian detective is that he had extraordinary access to all types and conditions of men and women, from the most celebrated to society’s outcasts, from the Prince of Wales to common prostitutes.

Dr Arthur Conan Doyle is central to Oscar Wilde and the Candlelight Murders – as he will be to the sequels in the series – but, in my book, he is not Wilde’s Dr Watson. That role falls to one Robert Sherard, a journalist, poet, ladies’ man, and Wilde’s first, most frequent and most loyal biographer. Sherard first met Wilde in 1882 in Paris and, throughout their friendship, which lasted until Wilde’s death in 1900, kept a detailed journal of their time together.

Oscar Wilde – dandy, detective, playwright, and, eventually, convicted corrupter of young men - died at about 1.45 pm on 30 November 1900 in a small, dingy first floor room at L’Hotel d’Alsace, 13 rue des Beaux-Arts, Paris. He was just 46. Exactly one hundred years later, in the same hotel, in the same bedroom (now expensively refurbished), a band of devotees - twenty or so of us: English, Irish, French, American - gathered to honour the man whose greatest play, according to Frank Harris, was his own life: ‘a five act tragedy with Greek implications, and he was its most ardent spectator.’

It was at 1.45 pm on that Thursday afternoon in Paris that I decided I wanted to write ‘The Oscar Wilde Murder Mysteries’. It was a memorable occasion. An Anglo-Catholic clergyman - a Canon of Christ Church, Oxford: he was tall and blond, called Beau and came from Cincinatti: Oscar would have approved - lit a candle and led us in prayer. There was a minute’s silence and some tears and, later, as we toasted the shade of the great man in champagne (absinthe is now outlawed in France), much laughter. We gazed in wonder at the huge turquoise peacocks decorating the wall above the bed and recalled Oscar’s last recorded quip: ‘My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has to go.’

Oscar Wilde has been a figure of fascination to me for as long as I can remember. I was born in 1948 in Germany, where, in the aftermath of the Second World War, my father was serving as a legal officer with the Allied Control Commission. He counted among his colleagues, H Montgomery Hyde, who, in 1948, published the first full account of the trials of Oscar Wilde. It was the first non-fiction book I ever read! (In 1974, at the Oxford Theatre Festival, I produced the first stage version of The Trials of Oscar Wilde, with Tom Baker as Wilde, and, in 2000, I edited the transcripts of the trials for an audio production starring Martin Jarvis.) In 1961, when I was thirteen, I was given the Complete Works of Oscar Wilde and read them from cover to cover - yes, all 1,118 pages. I can’t have understood much, but I relished the language and learnt by heart his Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young – eg: ‘Wickedness is a myth invented by good people to account for the curious attractiveness of others.’

As a child I felt close to Oscar for another reason. I was a pupil at Bedales School, where, in 1895, Cyril, the older of the Wildes’ two sons, had been at school. The founder of Bedales, John Badley, was a friend of Wilde’s, and was still alive and living in the school grounds when I was a boy. Mr Badley told me (in 1965, at around the time of his hundredth birthday) that he believed much of Oscar’s wit was ‘studied’. He recalled staying at a house party in Cambridge with Oscar and travelling back with him to London by train. Assorted fellow guests came to the station to see them on their way. At the moment the train was due to pull out, Wilde delivered a valedictory quip, then the guard blew the whistle and waved his green flag, the admirers on the platform cheered, Wilde sank back into his seat and the train moved off. Unfortunately, it only moved a yard or two before juddering to a halt. The group on the platform gathered again outside the compartment occupied by Wilde and Badley. Oscar hid behind his newspaper and hissed at his companion, ‘They’ve had my parting shot. I only prepared one.’

When I told this story to the actor, Sir Donald Sinden, he volunteered that, in the 1940s, when he knew him, Lord Alfred Douglas had told him, too, that much of Oscar Wilde’s spontaneous wit was carefully worked out in advance. Never mind how he did it - he did it. Bernard Shaw said, ‘He was incomparably the greatest talker of his time - perhaps of all time.’

John Badley told me, ‘Oscar Wilde could listen as well as talk. He put himself out to be entertaining. You know, he said, “Murder is always a mistake. One should never do anything that one cannot talk about after dinner.” He was a delightful person, charming and brilliant, with the most perfect manners of any man I ever met. Because of his imprisonment and disgrace he is seen nowadays as a tragic figure. That should not be his lasting memorial. I knew him quite well. He was such fun.’

One hundred and seven years after his death, I am still having fun in his company and if you read Oscar Wilde and the Candlelight Murders I hope you will, too. As Oscar once said, ‘There is nothing quite like an unexpected death for lifting the spirits.’

You can learn more on Gyles at www.gylesbrandreth.com

|

|