|

|

|

Crime and Punishment is one of those books. It has a unique power. The idea of it compels you even before you’ve read it. The stature of it too: it’s a masterpiece of world literature, a towering work that casts a long shadow. I remember how, as a precocious teenager who wanted to be a writer, I was drawn to it and scared of it at the same time. Dare I read it? Would I understand it? Would it disappoint me? Or – more likely - would it be so mind-blowingly brilliant that I would abandon all my own literary ambitions, realising that there was nothing more to be said, and no way left to say it? I should point out this was in the seventies. And one of the reasons I was so drawn to the book was that I’d heard that Columbo was based in some way on Porfiry Petrovich, the detective from Crime and Punishment. I was a big fan of Columbo (as I was of Kojak, and Ironside, and TV detective series in general). Given the kind of kid I was, I was also attracted by the idea of genius, by profound mysteries – by the promise of Russian literature in other words, even though I was frankly daunted by the prospect of tackling one of those big heavy books for real.

But here was a Russian book that was also a murder story; a philosophical novel that was also gory and gripping. There was an axe-murderer in it, for God’s sake! And a detective too. It seemed perfect, the perfect bridge from the Conan Doyle stories that I was lapping up to something more, well, ‘serious’.

At any rate, the idea of the book took hold of me and wouldn’t let me go. A little like Raskolnikov’s ‘idea’ in the book itself.

I seem to remember that the blurb on the back of the Penguin Classics edition of the time, which I must have borrowed from my school library, billed it as one of the world’s first detective novels. If so, this is slightly misleading. Although one of the characters is a detective, he is not the central character. In fact, Porfiry does not come on the scene until nearly half way through the book. He is directly present, I think, in just three chapters of the book. However, the idea of him is – masterfully - introduced before his entrance, and his dominating presence continues to be felt after he has left the stage.

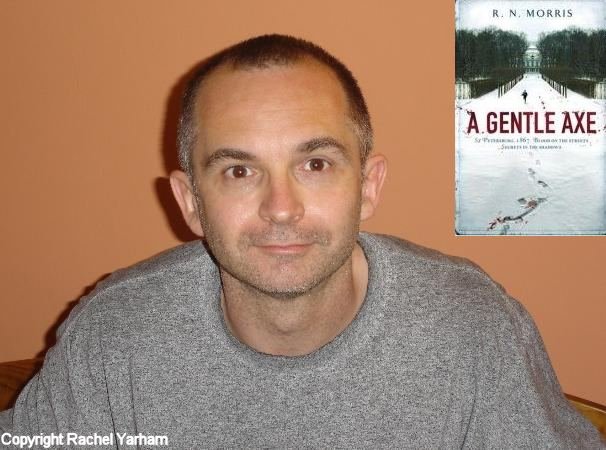

Of course, Crime and Punishment is not so much a ‘detective story’ as a ‘murderer story’, the murderer being Raskolnikov. I suppose my idea, really, was simply to switch things round and attempt to write the kind of detective story that the blurb had promised, but which Crime and Punishment so evidently is not - being, in fact, so much more. (I should say that A Gentle Axe is not a retelling of Crime and Punishment. It’s a different case altogether, taking place some time afterwards.) I’m fully aware of the monstrous effrontery of this conceit. That’s partly what appealed to me, I have to confess. But I hope people will realise the essential playfulness of my idea.

This idea - of writing a sleuthing yarn starring Porfiry Petrovich - came to me after re-reading the book many years later, in my thirties. I remembered my youthful expectations of the book, and how it had turned out to be something else entirely. I thought it would be a good idea for someone to do. Like most writers, I imagine, I tend to have a lot of ideas for books, most of which I never get round to doing anything about. Either because I discover someone else already has, or I decide that it would be just too hard to pull off. I felt this one probably fell into both camps: someone else must surely have done it – it seemed such an obvious idea. And I had no idea how I would go about it. For one thing, I didn’t know if I could write a crime novel; I certainly didn’t assume I could. And I knew nothing about nineteenth century St Petersburg. Hardly the best qualifications for the job.

But, whether I liked it or not, here was another idea that wouldn’t let go of me. I began to think there was something in it. I re-read Crime and Punishment again. I tried to find out if it had been done already, and as far as I knew, it hadn’t. I discussed it with my agent. ‘Yes, that could work,’ he said. That was all the green light I needed.

Naturally I went back to the original novel for clues in constructing my own Porfiry Petrovich. Clues like this description from Raskolnikov’s friend Razumikhin, who is a distant relative of Porfiry’s: ‘He’s a splendid chap, brother, you will see! He’s a little awkward. I don’t mean that he’s not well-bred; when I say that he is awkward I mean it in another respect. He is an intelligent fellow, very intelligent, he’s nobody’s fool, but he is of a rather peculiar turn of mind… He is incredulous, sceptical, cynical. He likes to mislead people, or rather to baffle them… Well, it’s an old and well-tried method… He knows his business, knows it very well… Last year he investigated and solved a case, another murder, where the scent was practically cold. He is very, very anxious to make your acquaintance!’

Dostoevsky quite often gives us such brief descriptions of characters who then turn out to be far more complex and elusive when we encounter them in the course of the story. Just like people in real life, you might say. Whatever one character says of another, in the end we form our own impressions, which are quite often difficult to pin down.

In Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky is sometimes credited with inventing what we might call the ‘limited third person point of view’. In fact, he began writing the novel in the first person, but instinctively realised that would not give him the freedom to tell Raskolnikov’s story as he wanted to. In typical style, he burnt that draft and began again in the third person. He needed to stay as close to Raskolnikov as possible, but also to be able to stand outside the character when necessary. It was a significant move away from the traditional ‘omniscient author’ approach and, I think, one of the things that make the book feel so modern. He does stick pretty rigorously to Raskolnikov’s feverish and vacillating point of view throughout the main part of the book, only occasionally committing misdemeanours of ‘head-hopping’ that modern day P.O.V. police would no doubt pull him up on. The point I want to make is that when we first encounter Porfiry, we view the scene, and form our impressions of the detective, from Raskolnikov’s point of view. In fact, our whole idea of Porfiry in the book is Raskolnikov’s idea of him. He exists as Raskolnikov’s nemesis. He is a mysterious force, there is something almost devilish – Mephistophelean perhaps – about him. He plays with Raskolnikov, but he understands him totally, and he is convinced from the outset that Raskolnikov has committed the crime. Certainly, Raskolnikov’s paranoia credits Porfiry with this.

What was interesting, writing a novel with Porfiry Petrovich as hero, is the clash between other people’s perceptions of him and his own ‘self-creation’, which I feel is governed by his professional role. That is to say he engineers and manipulates the impression he makes on the suspects and witnesses he interviews in order to extract information from them. I think it’s fair to say that I allowed myself some latitude in this. Also, in Crime and Punishment we are never afforded the privilege of seeing things from Porfiry’s point of view. Like Raskolnikov, we must try to work out what he is thinking by what he says and what he does. And I don’t think we can always trust what Porfiry says, either in Crime and Punishment or in my book. However, I do write at times from Porfiry’s point of view. I suppose imagining his internal perspective was the biggest leap, and liberty, that I took. And it is in this switch that I have had to create my own Porfiry Petrovich. It also brought up certain challenges, which I think are common to a lot of detective fiction. How to explore and reveal the character’s humanity, without giving away the solution of the mystery!

To return to Crime and Punishment, by the time murderer and detective meet, the sense of anticipation is enormous. Raskolnikov is going there in an attempt to take the initiative, but also because he wants to get a look at his adversary – and we, as readers, are impatient to meet Porfiry too. Razumikhin has taken Raskolnikov’s to the magistrate’s private apartment, not his office. It’s here that the first physical description occurs, which was very important to me, so I’ll quote it at length: ‘He was a man of about thirty-five, rather short and stout, and somewhat paunchy. He was clean-shaven, and the hair was cropped close on his large round head, which bulged out at the back almost as if it were swollen. His fat, round, rather snub-nosed, dark-skinned face had an unhealthy yellowish pallor, and a cheerful, slightly mocking expression. It would have seemed good-natured were it not for the expression of his eyes, which had a watery, glassy gleam under the lids with nearly white eyelashes, which twitched almost as though he were continually winking. The glance of those eyes was strangely out of keeping with his squat figure, almost like a peasant woman’s, and made him seem more to be reckoned with than might have been imagined at first sight.’

Clearly we’re not dealing with a dashing, handsome detective type, but nonetheless a formidable and fascinating character. Those eyes – and the eyelashes – drew me to him. A little later, Porfiry is represented as something of a prankster too. Razumikhin says of him: ‘Last year, for some reason, he assured us he was going into a monastery: he persisted in it for two months! Not long ago he took it into his head to announce that he was getting married, and that everything was ready for the wedding. He even got new clothes, and we were all congratulating him. He hadn’t got a fiancée or anything else; it was all a fraud!’

I have to say I found all this very suggestive. It was like a door opening, through which I could glimpse, or perhaps spy on, a very interesting personality indeed, mischievous, strange, humorous, perverse even, and not wholly trustworthy. How this informed the character I created, I can’t really say, as I am very much an instinctive writer. All I know is that it did.

Dostoevsky’s dialogue scenes in which Porfiry interviews Raskolnikov – or rather in which their intellectual and moral duels are played out – are of course brilliant, and it is here that we see the great investigator at work. Also brilliant is the way that Raskolnikov’s fascination with, and almost need for, his adversary grows throughout the book. Each respects the other. If Porfiry tries to play his ‘magistrate’s games’, Raskolnikov sees right through him. So Porfiry has to be on his toes, flexible and wily. He does his research too, getting hold of and reading an article that Raskolnikov had written. Again, this was a detail that made an impression on me, which I took hold of and ran with, if you like.

Essentially, though, my method was to encounter and enjoy Porfiry Petrovich in Crime and Punishment. And then write my own story, re-inventing the character for my own very different purposes. I hope Dostoevsky, wherever he is, is looking on with an amused and indulgent eye. A Gentle Axe, Faber&Faber paperback Feb. 2007 £12.99 |

| Webmaster: Tony 'Grog' Roberts [Contact] |