|

n 1212, some

70,000 children sent out in holy crusade for Jerusalem. They were to vanish

into history…

n 1212, some

70,000 children sent out in holy crusade for Jerusalem. They were to vanish

into history…

It sounds

fantastical, too bizarre to be true: tens of thousands of youngsters setting out

on doomed mission to the Holy Land to win it back for Christendom and retrieve

its holiest of relics The True Cross. But this is exactly what happened. In

the year 1212, some twenty years after Richard I, Coeur de Lion himself, had

tried and failed to defeat Saladin and storm Moslem-held Jerusalem, it was the

turn of the children to attempt the feat. Encouraged by child-preachers, and

convinced that only the young and pure-at-heart could succeed, they set out from

France and the Rhinelannd for the coast. What followed was to enter folklore as

The Pied Piper of Hamlyn. Now it has become the focus and foundation of my

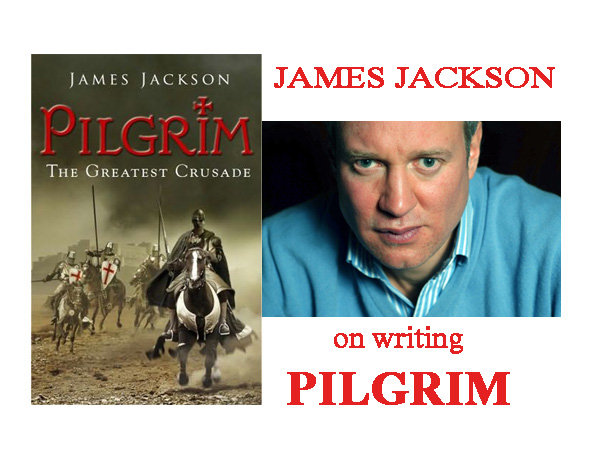

latest historical thriller,

Pilgrim.

This story

appealed to me on several fronts. Firstly, it was ‘hidden history’, concerned a

footnote in the Crusades that almost went unnoticed. Like my previous

historical thriller

Blood Rock, which deals with the stand of the Hospitaller Knights of

St. John against the 1565 Ottoman Turkish invasion of Malta, the backdrop is

truly epic and the stakes high. Unlike Blood Rock, it does not involve

the intensity and claustrophobia of siege, but instead follows children on a

true-life quest. Above all, the pathos and struggle of these youngsters was too

much to ignore. It was just one of those books that needed to be written.

This story

appealed to me on several fronts. Firstly, it was ‘hidden history’, concerned a

footnote in the Crusades that almost went unnoticed. Like my previous

historical thriller

Blood Rock, which deals with the stand of the Hospitaller Knights of

St. John against the 1565 Ottoman Turkish invasion of Malta, the backdrop is

truly epic and the stakes high. Unlike Blood Rock, it does not involve

the intensity and claustrophobia of siege, but instead follows children on a

true-life quest. Above all, the pathos and struggle of these youngsters was too

much to ignore. It was just one of those books that needed to be written.

The journey

these children attempted was extraordinary, and the landscape through which they

passed beset with hazard. It is not surprising that of the forty thousand

Rhineland children who set out from Cologne across the Alps less than a third

probably made it to the coast. Their compatriots in France who headed for

Marseilles suffered in similar fashion. That any made it at all was

remarkable. In about eight weeks during the summer of 1212, the young

Rhinelanders had managed to cover some 670 miles to Genoa. Factoring in one day

of rest per week, and considering the rudimentary footwear, the rough and

mountainous terrain, the lack of food and basic shelter, and the average

distance walked was still almost twelve miles a day. And all the while, the

children were weakening. Just for good measure, and in order to receive

blessing from the Pope, once they reached Genoa some of them went on to Rome.

Another 285 miles further on.

Perhaps it

was the lure of the True Cross that kept them going. Throughout Christendom, it

was considered the holiest of holies, the most sacred and revered relic ever to

exist. Its capture by Saladin and his Moslem army was the greatest of insults,

its retrieval the most important and heroic of quests. First identified in AD

326 by Saint Helena, mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine I, the ancient

artefact had variously been owned by invading Romans, Persians, and Frankish

Crusaders. Over the centuries, thousands had perished attempting either to

protect or recover it. It gave authority and legitimacy to those who possessed

it, reputedly had the power to heal. All very Indiana Jones. Now it was in the

hands of the hated infidel, and the children of France and the Rhineland were

determined to get it back.

The

mediaeval environment through which the children marched was a terrifying one,

more valley of the shadow of death than bucolic idyll. It was a world of

superstition and religious fervour, of arbitrary justice and cruel persecution.

Allegations of spells and witchcraft abounded. In fact, burning of witches was

so common that history relates one incident in which an entire German town

burned to the ground when the fat from several hundred suspected witches put

simultaneously to the stake ran in the streets and set fire to surrounding

buildings. Bitter-sweet revenge.

Other

terrors existed. One religious sect believed there was a finite amount of evil

in the world, that it required using up before Jesus would return. The result

was a crime and killing spree. On similar lines, other groups thought the world

could only be cleansed through the expending of mortal sin. Sexual excess and

feeding frenzy erupted, and all in the name of God. Less orgiastic were the

religious zealots who grazed the fields as oxen, believing that Man was unworthy

to stand upright in the sight of God. And on the matter of sight, some plucked

out their eyes so as to avoid corruption through the contemplation of material

things. Finally, there were the Cathars – beloved of The Da Vinci Code –

who were dualists convinced in the existence of a good god representing the

human spirit and a bad god manifesting itself in material flesh. Strange times,

stranger people.

In the Holy

Land, still greater dangers lurked. Here, rulers tended to die in strange

circumstances: Henry of Champagne fell out of his window, along with his pet

dwarf named Rose. King Amalric succumbed to a ‘surfeit of fish’. And Prince

Conrad of Tyre was slain by a group of Assassins posing as priests. Forget Al-Qa’eda,

the Assassins – or hashashshin, meaning hashish-eathers in Arabic – were the

real thing, the world’s first true terrorist organisation. Chaos was their aim,

murder their method. Based in fortresses set atop high mountains in Syria, and

trained in the art and science of killing, they were ruthless, dedicated, and

open to commissions. Hire them, and their sheikh would prove their commitment

by ordering several of his followers to jump to their deaths from the castle

walls. Promised virgins and eternal reward in Paradise, they obeyed. It might

all sound chillingly familiar. Small wonder that in Pilgrim a leper knight of

St. Lazarus comments: ‘Everything turns rotten in the Holy Land’.

So the

children travelled on. Once at the coast, there was further blow to their

morale and fortunes. Their boy-preachers had promised that the seas would part

to allow seamless and dry onward journey to the Holy Land. When this failed to

happen, many gave up all hope. It is said that some Genoese families today

contain German bloodlines through the children adopted into them at the time.

But a few pressed on, boarding ships whose merchant-owners offered safe passage

to Palestine. The same occurred in Marseilles, where French survivors of the

great trek embarked too on the seaward leg of their adventure. The children had

walked into a trap laid by the human-traffickers of the age. Thousands were to

be shipped out and sold on to Arab traders and end in chains in the

slave-markets of Alexandria, Damascus and Baghdad. White northern-European

skins carried a high value in Arabia. A terrible fate and one from which most

would never reemerge.

Yet an

individual did. In 1230, almost twenty years after the children set out on

their ill-fated expedition, a young priest arrived in Europe and claimed to be a

survivor from that vanished host. He told a harrowing tale, of shipwreck and

death, of hardship and servitude, of how those who had refused to convert to

Islam were executed and how those who lived were carried off into darkness.

Some might

argue that the story of the Children’s Crusade is neither cautionary nor

relevant for our modern age. Others would claim it is merely a footnote, a tale

that has come down to us in folklore-form alone. But even half-remembered

legends and fairtytales can serve a purpose and carry a truth. They remind us

of the horrors inflicted upon children by adult neglect, greed, and stupidity,

of the evils perpetrated in the name of unquestioning obedience to religion or

ideology. Today around the world, there are children mired in poverty, children

forced into soldiering or prostitution, children kept in sweatshops and

slavery. Lest we forget, and lest we think the Children’s Crusade lies in the

past.

Yet there

is also hope. Above all else, those pitiable events of eight hundred years ago

teach us of the raw courage and fortitude of the young. They remind us too of

the power of the quest, of the human need to have something to believe in.

Maybe we are all of us in some small way in search of that one True Cross.

PILGRIM

is published by John Murray on 24th July 2008.

Price: £12.99

|