|

I

’m going to describe the hero of

my new novel, Empire of Sand. It’s not

always a good idea to do this. Most authors would rather offer a few

brushstrokes and allow the reader to colour the rest in for themselves.

I don’t have any choice. Mine is real, you see, captured in

photographs and moving pictures. You are just a few keystrokes away

from pulling up an image of him, so let me save you the trouble.

He

goes

like this: first off, he is short. Five foot five is a generous

estimate and some believe him to be a good four inches shy of that. His

head is too large for his body, possibly because a childhood accident

– a broken leg he ignored for several days –

stunted his growth. He has what dentists call a Class Three Occlusion.

If I say Bruce Forsyth or Jimmy Hill, you’ll get the picture,

although his is less pronounced. He has a strange laugh, especially

when nervous, an effeminate high-pitched giggle. He is often scruffy

and shambolic.

He

goes

like this: first off, he is short. Five foot five is a generous

estimate and some believe him to be a good four inches shy of that. His

head is too large for his body, possibly because a childhood accident

– a broken leg he ignored for several days –

stunted his growth. He has what dentists call a Class Three Occlusion.

If I say Bruce Forsyth or Jimmy Hill, you’ll get the picture,

although his is less pronounced. He has a strange laugh, especially

when nervous, an effeminate high-pitched giggle. He is often scruffy

and shambolic.

Then

there is his personality. Some find him charming and erudite, but just

as many think him an insufferable bore. If he doesn’t approve

of you he can be taciturn or plain rude. He most certainly is a liar,

who doctors the truth to serve own purposes. His sexual orientation is

murky, but he pays a burly man to visit him and

‘punish’ him, with a severe beating, for a series

of imaginary misdeeds. He both courts fame and is repelled by it.

So,

the

hero of my novel is a short, oddly proportioned lying bastard. Welcome

to Lawrence

of Arabia.

Except,

of course he wasn’t. Lawrence of Arabia didn’t

exist. He was invented by Lowell Thomas, an American journalist and

showman who produced an enormously popular stage show, with a lecture,

slides and moving pictures which turned an often squalid guerrilla war

into a romance about a desert warrior. Once a day, twice on Saturdays

and Wednesdays, the White King Of Arabia led the noble Bedu in a fierce

campaign to free their lands from Turkish shackles. No mention of

British gold driving the enterprise, the inter-tribal feuds, the

sickening massacres on both sides, the political double-dealing or the

pivotal role played by General Allenby. (There had been originally but

it was edited down when it became clear it was Lawrence

audiences loved, not ‘Bull’ Allenby.) It was about

as authentic as Rudolph Valentino’s The Sheik, which came out

in 1921, while Thomas was still doing the rounds.

Nor was he Thomas Edward Lawrence; his father, an Anglo-Irish squire,

had run off with the family governess and had five illegitimate sons,

of which ‘Ned’, as they called him, was the second.

The father’s name was really Chapman; the Lawrence

family, like Lawrence of Arabia, was a

construct. Luckily I have one thing on my side when it comes to forging

my central character from this mish-mash. He comes riding out of the

rippling desert mirage and as the features solidify from the

super-heated air we can see it is Peter O’Toole, star of the

movie version of Lawrence of Arabia. He is a good foot taller than Lawrence,

blonder, too, with a chiselled

face and piercing blue eyes. Now, HE looks like a hero.

And indeed, the Irishman has

superseded the real man in

the public imagination. No wonder Noel Coward said that if

O’Toole had been any prettier they would have had to call the

movie Florence of Arabia. So, like a palimpsest, my genuine hero is

erased and a new one of far finer features painted over him.I

don’t have to tell the reader anything about this

man; if need be, O’Toole will supply the face and the voice.

But

why

would I choose to write about Lawrence

at all? For all its faults (and TEL scholars will bore the bishti off

you detailing its historical hiccups), David Lean’s epic

captures the essence of the Lawrence

story, at least as outlined by the author of Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

Lowly, bumbling mapmaker/archeologist plucked out of Cairo

office and manages to win the trust of the Arabs. Aids in the Arab

uprising against the Turks (designed to weaken the Ottoman

Empire,

Germany’s

ally) on the understanding that the tribes will be rewarded with

independent homelands. Embittered by war and betrayed by the British

and French governments, who have no intention of giving Arabia

to the Arabs, he returns to England

a disappointed man. He tries to

reverse ill-advised political carve-up of the Middle

East

at the Paris Peac conference of 1919 and two years later in Cairo.

He fails. (And we are still

living with the consequences of that.)

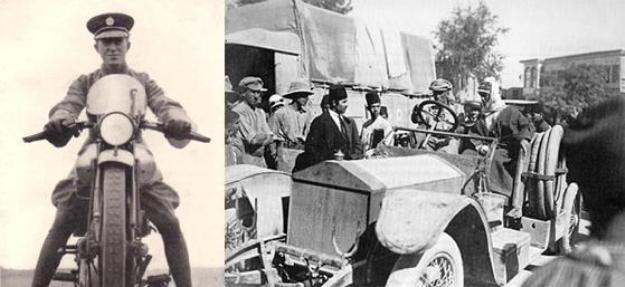

Suffering

from post-traumatic stress, he seeks anonymity in the army and RAF at a

lowly rank, but is hounded by the press and the Lawrence of

Arabia

monster he helped create,

assuming the show would garner support for the Arab cause, rather than

simply making him a celebrity. After a few happy years working on the

Schneider Trophy seaplanes that would, eventually, give birth to the

Spitfire and helping design the fast RAF rescue boats that would

save downed pilot’s lives, Lawrence eventually dies

in a somewhat mysterious motorcycle crash (think Princess Di) in

Dorset, aged just forty six.

My

intention was never to go over this story, at least not the central

section that made him famous, the revolt in the desert. Although

research in recent years had thrown up interesting inconsistency in his

accounts, such as the fact his infamous buggery by the Bey at

Dera’a may have been a total fabrication and that Lawrence

was far from the only Allied officer fighting with the Arabs; he

wasn’t even the first one to blow up Turkish train on the Hejaz

railway. Nor was he the first into Damascus;

New Zealand

troops beat him to it by a day.

The Arab liberation was a carefully staged fiction, much like de

Gaulle’s liberation of Paris,

almost a quarter of a century

later.

Fascinating

though they were, none of the new discoveries really changed the arc of

the story or altered the fact that Lawrence

did remarkable things. It took a special kind of man, one not hamstrung

by British conventions or attitudes, to deal with and win the respect

of volatile figures such as Emir Feisel (Alec Guiness in the movie, too

old for the part) and the fiercesome

‘outlaw’ Auda Abu Tayeh (Anthony Quinn).

Although Damascus

was the culmination of the campaign, Lawrence’s

greatest feat was probably taking the port

of Aqaba

from the rear, a strike in which Auda was instrumental but the

Englishman certainly planned. (Deduct two points if you instantly

thought that wasn’t all he took from the rear in the desert;

there is no real evidence that he was actively homosexual).

But

all

that is up on the screen. I didn’t want to novelise the

movie, in other words. But I still wanted to write about him. I needed

a way in. I wasn’t sure the later years were able to sustain

the type of novel I had in mind, where TEL could still be heroic,

rather than a broken, haunted man. So was there scope for a prequel,

set before the Arab Revolt, which began in June, 1916? Then I found

William Wassmuss.

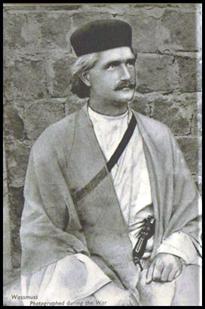

Wassmuss

was a blond and blue-eyed German, with a penchant for self-promotion

and a predeliction for wearing native garb out in the desert. He loved

the tribespeople of the Middle

East,

encouraged them in revolt, telling a few fibs along the way, and, after

the war, did his best to help them. He set up farms and irrigation

systems in the bleakest of parched lands and lost everything on the

scheme. He died, forgotten and pfennigless in 1931.When his biography

came out in 1935, it was called Wassmuss:

The German Lawrence.

Wassmuss

was a blond and blue-eyed German, with a penchant for self-promotion

and a predeliction for wearing native garb out in the desert. He loved

the tribespeople of the Middle

East,

encouraged them in revolt, telling a few fibs along the way, and, after

the war, did his best to help them. He set up farms and irrigation

systems in the bleakest of parched lands and lost everything on the

scheme. He died, forgotten and pfennigless in 1931.When his biography

came out in 1935, it was called Wassmuss:

The German Lawrence.

So, I realised when I discovered the book, TEL had an alter ego among

the enemy. In 1915, Wassmuss was galvanising the tribes of Persia

to rise up against the British, who needed to control the Gulf because

of the oil coming out of Basra’s

refineries which kept the Royal Navy

steaming (you can join the dots to today there). Wily Wassmuss told the

tribes that the Kaiser had converted to Islam and made the hajj to Mecca,

thus ensuring their loyalty to Berlin,

not the infidel British. He

became such a thorn in Basra’s

side that huge rewards were offered for

his capture. The whole story has strong echoes of John

Buchan’ prescient Greenmantle, which

came out the same year.

Where

was Lawrence

while his was going on? According to the

film, he was a bumbling fool in Cairo.

Well, he was certainly eccentric, but no

idiot ingenue. In fact, according to investigations by Philip Knightley

and Colin Simpson of The Sunday Times in the late sixties, he was

running spies, interrogating Turkish prisoners and gathering

intelligence. He worked eighteen hour days at it, scorning the social

circus that was wartime Cairo

(polo or racing at Ghezira, tea at

Groppi’s, cocktails at Shepheard’s, dinner at the

Continental). Lawrence

would have at least have heard of Wassmuss and the other German agents

trying to destabilise the

British Empire.

It

is

not beyond the bounds of possibility that Lawrence

was asked his opinion about the Kaiser’s man in Persia.

Lawrence

was certainly sent ‘On Special Duty’ –

clandestine missions for the Intelligence services - at least twice

before the Arab revolt. In 1916 he was despatched by the fledgling Arab

Bureau to Mesopotamia

(Iraq),

ostensibly to bribe a Turkish commander with a million pounds to

release the ten thousand British soldiers he had surrounded at Kut

(north of Basra

on the Tigris).

The Turk refused. The British surrendered and most of the men, but not

the officers, died of disease and malnutrition on a hideous forced

march.

But

there was an earlier, sketchier mission, which had Lawrence

travelling to Athens

to ‘improve liaison’. What, I thought, if

that was a cover? After all, Kut had a dual purpose. As well as trying

his hand at bribery and corruption, Lawrence

was instructed to meet with Arab

nationalists in

Basra

to sound them out about a possible Arab

Revolt. What if Athens

was another piece of chicanery? What if it was a cloak for Lawrence

to track down and neutralise the increasingly dangerous Wassmuss?

This

is

what Empire of Sand became, a fictional version of

an encounter between two genuine historical figures. When asked to

outline it to my publishers, I said: ‘It’s Heat. In

Persia.’

I meant the Pacino/De Niro movie, not the climatic conditions. I

planned an equivalent scene to the pivotal meeting of the principals in

a diner, where both men come face to face just once. Cop and thief.

They respect and maybe like each other, but know they are on opposite

sides and if they have to kill, it won’t be personal.

In

the

end, it didn’t quite work out like that. You try finding a

diner in

Southern Persia

to stage a meet. But it’s still a cat-and-mouse game between

the pair of them in Cairo

and the deserts and mountains

around

Shiraz.

In order to make sure this earlier

version of Lawrence

connected the reader to Feisal’s desert commander (and, yes,

the movie) I book-ended the 1915 scenes with a prologue and epilogue

set during the Arab revolt.

The

idea was to show how at least some of TEL’s later precepts of

guerrilla warfare (still used today by insurgents the world over) were

influenced by the audacious Wassmuss. I also wanted to write the story

without delving too much into his sexuality. It seemed to me this was a

side issue, a very modern preoccupation, driven by Lawrence’s

enigmatic dedication to ‘S.A.’

at the beginning of Seven

Pillars. The TEL industry has been powered by those few lines for

years. It was time to let it lie. So he liked a little male BDSM? These

days that would hardly make a blog. I wanted to take the story back to

the man of action. Which means he gets to blow up a train, climb down a

well to diffuse a bomb and is forced to kill a wounded servant, all

actual events. I also wanted to show his love for machines: he adored

motorcycles, airplanes, guns of every description and Rolls Royce

armoured cars (he eventually traded in his camel for one of the latter).

So,

what does my hero look like to me? Is this TEL the giggling little guy

with the big head or is it a young, impossibly handsome Peter

O’Toole yelling ‘No prisoners!’ while

waving a sword.

I

must

admit I edited out the giggle on a second draft. It was just too

annoying, especially after I watched Ralph Fiennes attempt it in A

Dangerous Man, a Lawrence of Arabia sequel. It might have been

accurate, but it was incredibly alienating and annoying. And although

there is a reference to his size early on in the novel (using his own

description of himself as a ‘pocket Hercules’

– he was very fit and strong with incredible stamina and a

high threshold for pain), for the most part I do the equivalent of

pleading the Fifth. I don’t describe him, only his actions,

because it might incriminate me, as during the writing, some days he

looked like the real Lawrence

and other times, in certain

lights, a dead ringer for O’Toole.

In

the

final draft I made a conscious effort to meld the two images into one,

giving me a consistent visualisation of the character. So what does he

look like? Well, as far as I am concerned if you pay your ten quid for

the book, he can look any way you damn well please. That’s

fine by me. I’m done with Lawrence.

He’s your hero now, if you want him.

Empire of Sand

is published April 2008 in hardback at £10 by Headline.

Click Here to read the Shots review

http://www.robert-ryan.net/

Click on the image to visit Crime Files Magazine (www.crime-files.co.uk)

|