|

When Harry Met Ripley....

Thankfully, I have never

needed to use the full appellation “Henry Reymond Fitzwalter

Keating”. On book

jackets and in by-lines and indices “H.R.F.

Keating” seems to suffice, saving

valuable keystrokes, and in person the man himself is more than happy

to be

referred to as “Harry”.

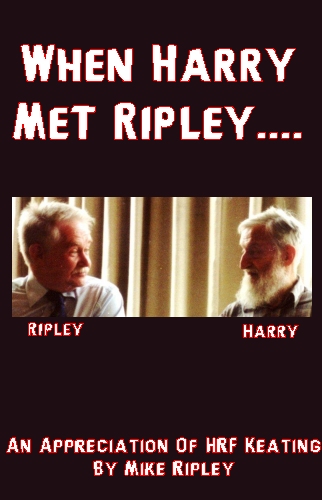

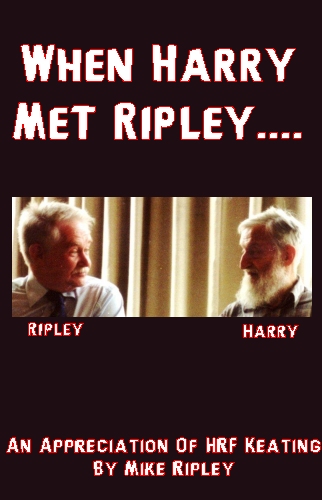

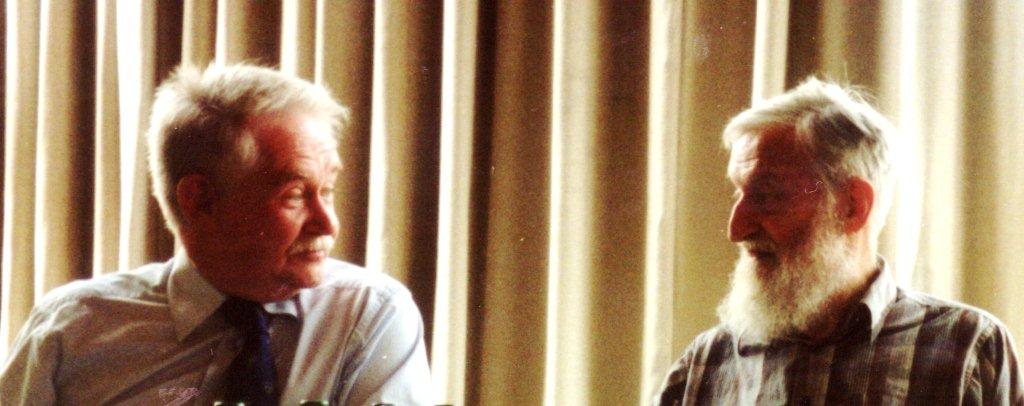

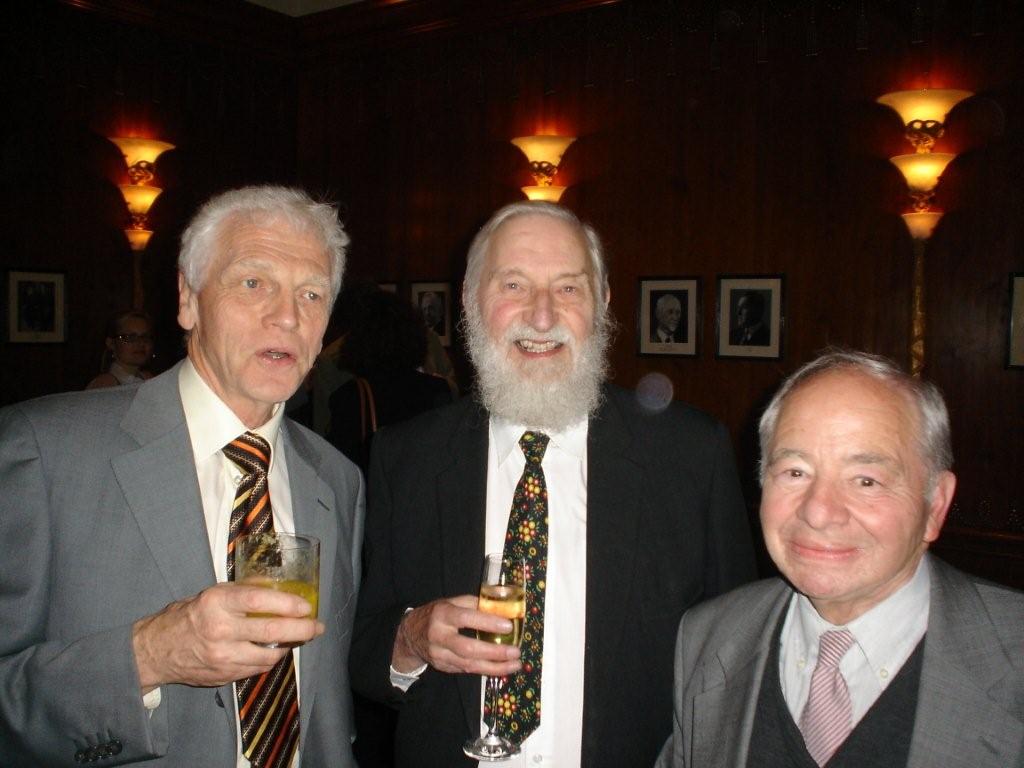

Harry Keating and Mike Ripley not quite eyeball to eyeball in a panel

discussion on plotting a crime novel at Girton

College,

Cambridge,

2007.

He has a name, which once seen in print is

not easily forgotten and I saw the name long before I ever saw, let

alone met,

the man. I saw his

name everywhere in

bookshops and indeed on the covers of books, yet not his

books, for as I was discovering the thrill and diversity of

crime fiction, I found myself following a trail of clues indicating

‘something

interesting in here’ in the form of one- or two-line

recommendations on dust

jackets signed by the (then) mysterious “H.R.F.

Keating” in his capacity as

crime fiction reviewer for The Times.

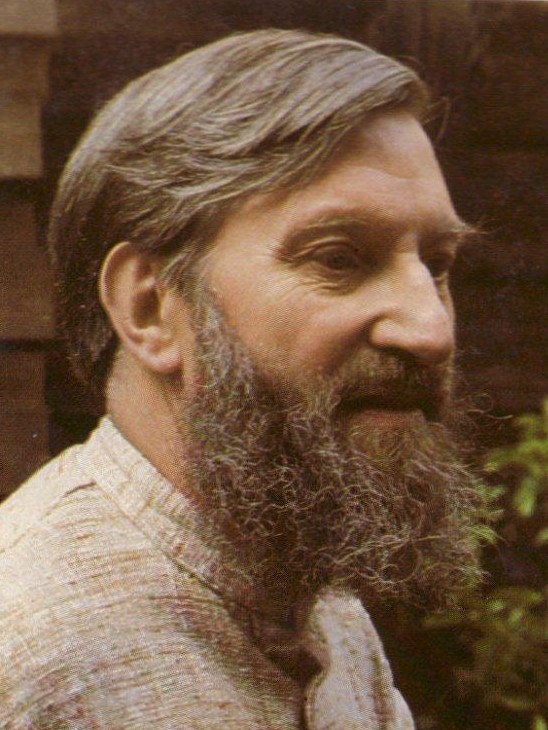

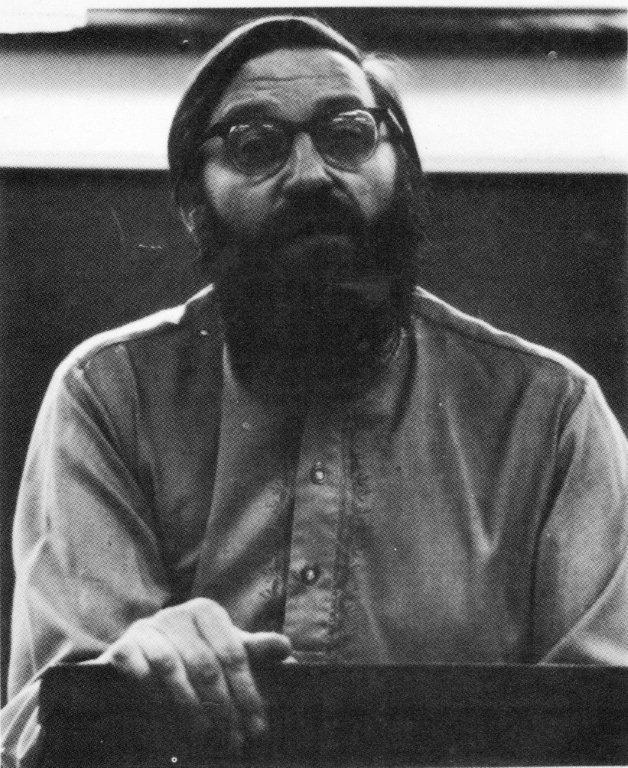

HRFK in 1982.

I never actually read The Times

(the Yorkshire Post

was the journal of record in my youth and we regarded The

Times as dangerously left-wing and, worst of all, southern) but I followed those Keating

recommendations – which would be called

‘blurbs’ today – and found I was rarely

disappointed. For example, he described Lionel Davidson’s The Chelsea Murders as “An

entertainment...A puzzle. A black

comedy. A pleasure through and through.”

He was right on all counts and though I had already

discovered Davidson,

I found myself agreeing with the mysterious Mr Keating and so allowed

him to

direct me towards authors I didn’t know, using him like a

fraudulent psychic would

call upon a spirit guide.

No dodgy table-thumping or displays of

ectoplasm here though, for his suggestions were always solid and

without them I

would never have discovered Frank Parrish’s Fire

In The Barley (“well-conceived, excitingly paced

story”); the wonderful

stylist P.M. Hubbard’s A Thirsty

Evil (“Acquire

the Hubbard taste, it’s richly rewarding”) and the

amazing Anthony Price’s The

Labyrinth Makers (“One of those

books you simultaneously want to finish and long to go on for hours

yet”). There

were certainly many others and then my reading expanded geometrically

when in

1982 I was given that indispensible guide to the genre Whodunit? The editor was,

of course, H.R.F. Keating.

A trio of Diamond Dagger winners: Peter Lovesey, Harry Keating and Colin Dexter. [Picture: Ali Karim]

But by that time I had detected that

‘HRFK’

had written a few books himself and indeed was quite famous for writing

a

series of crime novels with an Indian detective even though he himself

had

travelled no further east than Dover – or so the legend went

– and thus my

first meeting with Inspector Ganesh Ghote, who had actually burst on to

the

crime scene in The

Perfect Murder in 1964.

Meeting with Ghote’s creator recently, in,

ironically, the year of Slumdog

Millionaire, though in his comfortable, book-lined home in

Notting Hill

rather than in Mumbai, Harry is disarmingly open (as he always is)

about the

creative process behind that auspicious debut.

Harry making a point to another past Chairman of the Crime Writers

Association, Catherine Aird.

He had, in fact, had five novels published

BG (Before Ghote), which, according to the reviewers of the day, were

all said

to be witty, lively and thought-provoking, if highly contrived. Some of

the

titles also betrayed a mischievous taste for the surreal, such as Zen

There Was Murder and The Dog It Was That Died, with

one

of the most striking Penguin covers ever.

They were not, however, finding a

publisher in America

and Harry and his agent agreed this was a two-pipe (if not quite three)

problem

which needed to be solved. Perhaps the answer lay in a new, more

exotic, setting and

so, practical as ever, Harry “sat

down with an Atlas and flicked idly through it until I got to Page India”.

The rest, as they say, was history – or at least 26 novels

and goodness knows

how many short stories in the Ghote canon, so far.

A younger, more

serious, Harry at the podium delivering a lecture.

That initial outing for the unassuming

little Bombay CID

man won Harry the first of his CWA Gold Daggers and also many loyal

fans, not

surprisingly as this was less than 20 years since the formal end of The

Raj and

large numbers of British readers had served in India,

remembering it with affection. What was surprising, or so Harry

modestly

insists was how “astonishingly well” the book was

received in the USA, where it

was reviewed by Anthony Boucher no less, who named it his

‘book of the year’

despite the year being only three or four months old.

Considering that his actual experience of India

was nil Harry must have done his research well, for, as he says with a

smile,

“there were not many complaints” which was quite an

achievement given the large

number of ‘old India

hands’ still around in 1964. Harry did, however, get a letter

of complaint from

a self-styled ‘Guru’ (it was the Sixties after

all), although on closer

inspection this turned out to be an appeal for contributions to the

Guru’s own

personal school of philosophy.

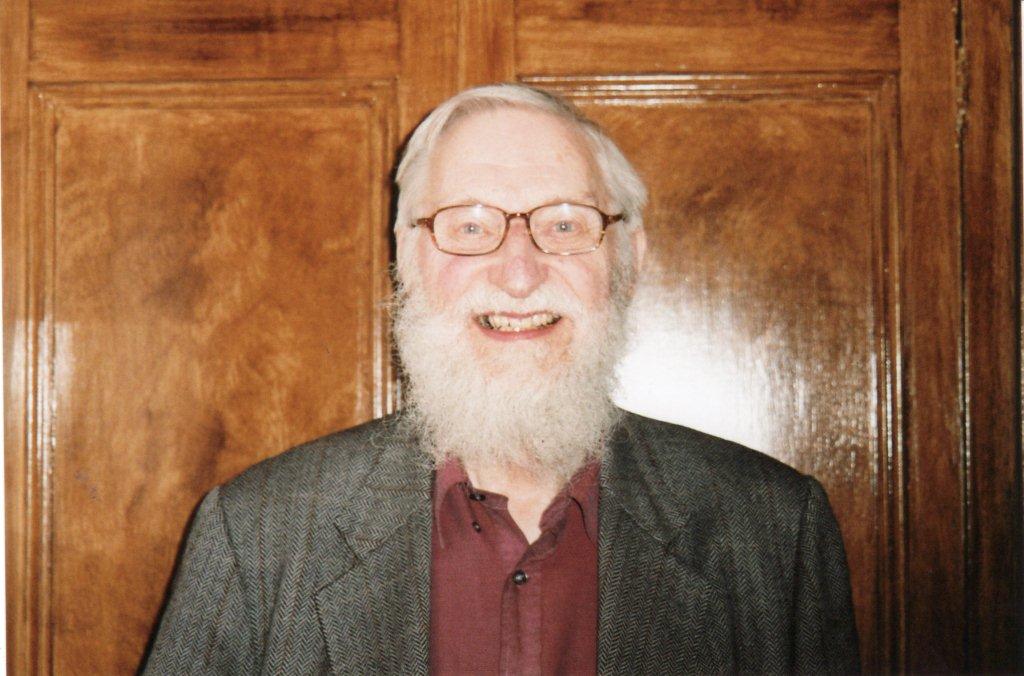

Harry in March 2009.

Ghote, thought Harry, was a good enough

character to pursue for a further two or three books and Inspector Ghote’s Good Crusade and

Inspector

Ghote Caught in Meshes promptly followed and were

received so well that

“it was an obvious choice to stay with him”. So he

did, with a new title almost

annually.

It may seem that Harry was defying the old

maxim that you should write about what you know and he cheerfully

admits that

“it was all going quite nicely without having to face the

actuality” but then

one morning the actuality came calling. It was at the breakfast table

with the morning

post (those were the days!) that Harry opened a letter from Air India,

which

basically said: You’ve been writing

about

India, now come and see it and offered him a ticket,

thankfully as return

one, on one of their flights to Bombay, as it was then. It was an offer

Harry,

in all conscience, could not afford to refuse.

The Ghote books were known and read in India

but still, the prospect of confronting the

“actuality” of a world he had

created in the safety of Notting Hill several thousand miles away, must

have

been daunting if not nerve-wracking. Harry spent the entire Air India

flight there calming his nerves and rehearsing an appropriate speech

for that

dramatic moment when he landed and stepped for the first time on to

Indian

soil. It went, as he recalls, “Something along the lines of

‘One small step for

Inspector Ghote...’” but in reality the speech was

never delivered. As the Air

India jet landed and Harry stepped on to the tarmac of Bombay

airport, his first historic words were: “My God,

it’s hot!”

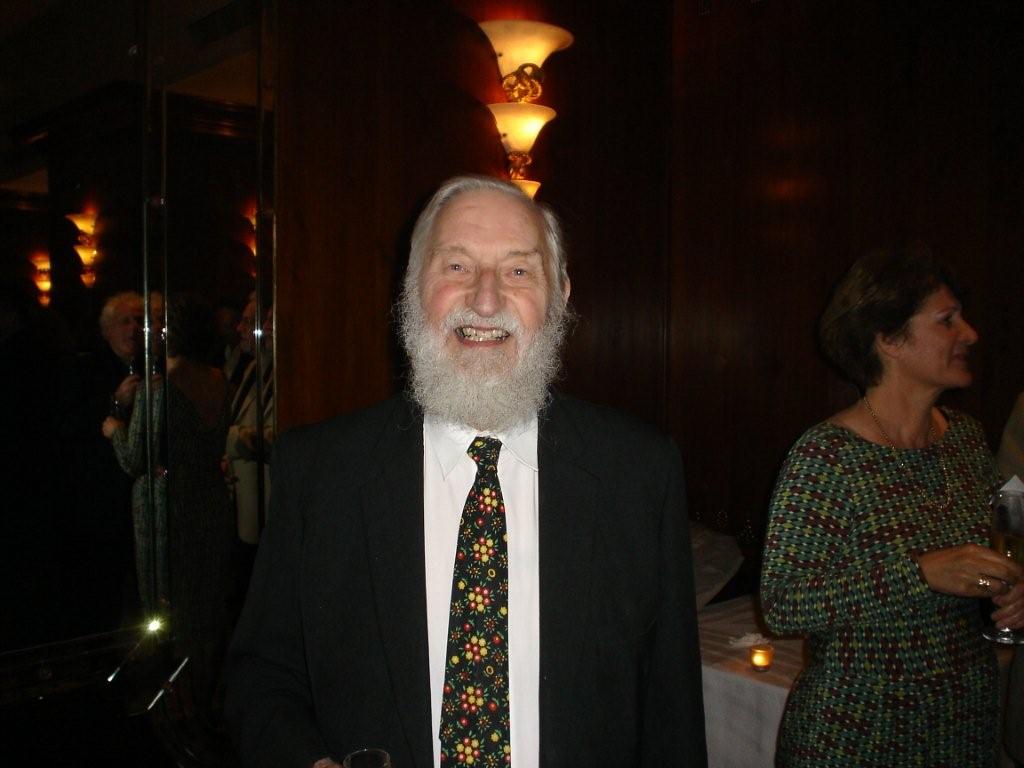

Harry in 2005. In the background, no doubt casing the joint, is crime writer Denise Danks. [Picture: Ali Karim]

To say Harry was warmly received in India

would be to stoop to a pun too far and certainly not one he would make

without

squirming with embarrassment, but it marked the start of a fruitful

partnership

and eventually brought Harry a walk-on cameo role in the 1988 film

version of The Perfect Murder,

produced by Ismail

Merchant. Harry goes to Bollywood?

Not a

bad progression for someone who had discovered India

in an Atlas in Notting Hill.

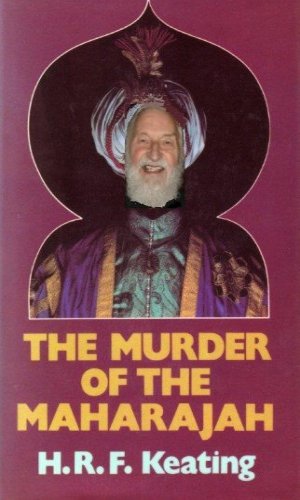

And India

served him well, earning him a second Gold Dagger for The Murder of the Maharajah

in 1980. Set in the Indian state of Bhopore in 1930, this was

Harry’s transposition

of the classic country-house

murder involving a fiendishly clever method of murder –

though he did get

letters this time from old India

hands claiming it was implausible!

With

its height of the Raj setting, this is often dismissed from the Ghote

Canon as

a ‘stand alone’ novel as,

in 1930,

Ganesh Ghote would hardly have been born. But I am not so sure. The

unsuspecting reader should read the last two paragraphs very

carefully...

There was a too-short-lived BBC

adaption of the Ghote stories and the books themselves continued

(although

Harry wrote many non-Ghote books) up to Breaking and Entering,

published in

2000, when it was announced to a startled world that the series would

end. It was a

decision reached on the advice of his

agent; though Ghote would not retire, be promoted (being kicked

upstairs is a

well-worn exit strategy), be killed or die of drink, he would just cease.

Harry, of course, would not retire, rather he would

concentrate on a new

series featuring policewoman Harriet Martens (a more fashionable

detective?) who

appeared in The Hard

Detective in the year Ghote seemed to disappear.

To

make the break a clean one and mark the end of an era, Harry consigned

all his

Ghote (and India) files to

a Royal

Borough of Kensington recycling

bin,

much to the annoyance of his long-suffering wife Sheila (Mitchell, the

actress).

Zia

Mohyeddin as Inspector Ghote in a 1969 BBC

dramatisation.

But Ganesh Ghote was far too good a

character to go quietly into the night or be filed as ‘Not

Needed On Voyage’ in

the luggage compartment of a novelist’s imagination. After

seven Harriet

Martens books, which had their fans and which were expertly read on

audio books

by Sheila Mitchell, the call of the Ghote became too much to resist and

in

2008, he returned triumphantly, and cunningly, in a prequel

to his 1964 debut, in Inspector

Ghote’s First Case.

At exactly what point Harry began to

“roundly curse” himself for recycling all his Ghote

files is not known, “but

fortunately I still had the little notebooks I always keep when

writing”. He

also had a prime source of research at his fingertips: the two dozen

Inspector

Ghote books already published! There can be few writers who can have

had the

luxury of such a rich supply of source material. And so close to hand!

As a prequel set in 1964, the book also

qualified and was indeed shortlisted for the 2008 Ellis Peters Award

for

historical mysteries. The other short-listed authors must have hated

Harry.

Whereas they had had to spend months if not years researching London

during the Blitz, 12th century England,

post-war Argentina

or the Edwardian railway system, all Harry had to do was read his own

back

catalogue!

Which of course he did – the whole lot

– and

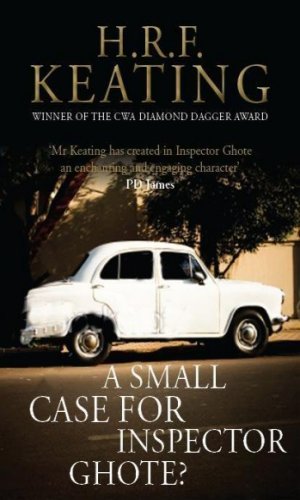

he must have quite liked them, for next month sees the publication of

another

‘historical’ Ghote, A Small Case for Inspector Ghote?

again set in the early 1960s.

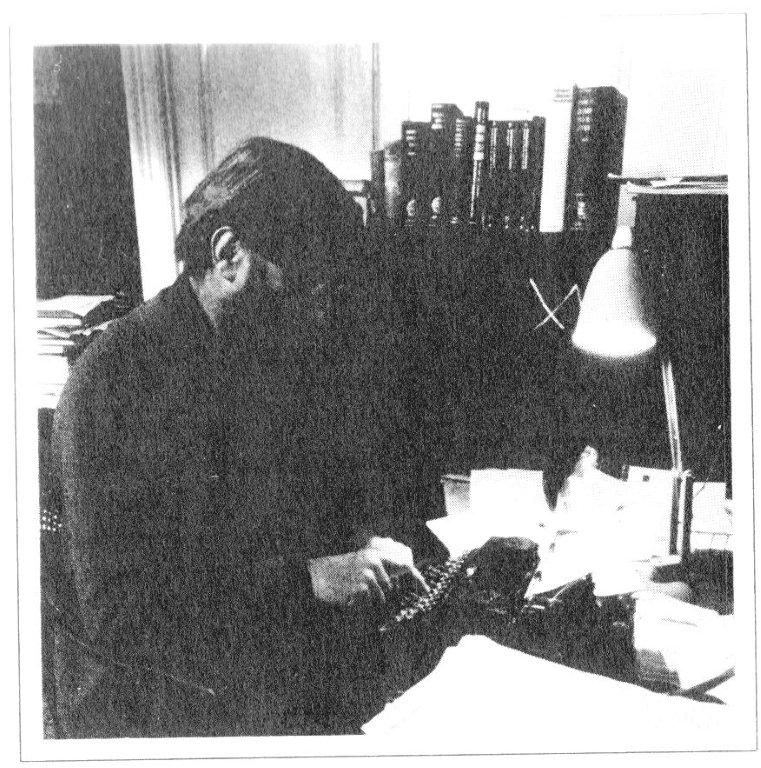

Harry bashing away on a faithful typewriter in the late 1970s.

To Harry it makes perfect sense to

concentrate on Ghote’s early career as to revive the

character in 2009 Mumbai

would mean a very old character and one not of a time with the Slumdog Millionaire city of Mumbai. Whatever, Harry certainly seems to be

enjoying Ghote’s return and there is a typical Keating

subtlety in the addition

of a question mark to the title of the new book. That, Harry confides,

makes

all the difference, for Inspector Ghote’s (latest)

‘small’ case turns out to be

anything but a small case in fact it threatens to be a career-ending

(almost

before it has begun) case.

But why does Ghote work as a

character? He is

surely the most

unassuming, most un-heroic hero in modern crime fiction. One might

almost say

(as I did) that Ghote’s most heroic quality is that he is

totally un-heroic and

is therefore continuously and professionally underestimated by his

foes. Why should Ghote work as a

character?

“I could answer...” says Harry, then

pauses

to add the caveat, “...but it would be a bad

answer.... because he’s me. Both he and I worry about what

people think of us.”

Ghote is no genius like Sherlock Holmes –

on whom Harry is a recognised authority – and no white knight

of the mean

streets like Philip Marlowe. He does, it is true, use Holmesian

deductive

methods but adds to them a crucial understanding of the complex local

culture.

In this it is almost a case of the detective as cultural anthropologist

and he

shares common ground with the detectives created by Tony Hillerman and

James

McClure, yet Ghote’s gently probing curiosity into how human

beings deal with

life puts him, I would suggest, in the same filing cabinet of fictional detectives which

contains Simenon’s

Inspector Maigret.

Harry is not displeased with the

suggestion and agrees that, like Maigret, Ghote isn’t so much

a real policeman

as a composite, mythical one and he is quite right when he points up

the

similarities between himself and his fictional hero. Both are extremely

polite,

diplomatic and gentle; so it wasn’t a

“bad” answer, for in a very good way,

Harry is Ghote.

It is something I had suspected long before

out meeting in Notting Hill in Harry’s study where, framed on

the wall, is the

first (and only) typewritten page of Jim’s

Adventure, Harry’s first foray into fiction

– crime fiction of course – at

the age of 8!

It may be the first time I have ever seen

this particular historic document, but it is not the first time I have

met

Harry; far from it. I think we first met round about 1990 at, if memory

serves,

a party in a fashionable London

hotel to mark the launch of a new Peter Lovesey novel. It was a notable

event

for me, for not only did I get to meet Harry, but also Julian Symons

and thus,

in the space one cocktail (or perhaps two) I had touched base with the

two main

critical analysts of the British (nay, global) crime fiction scene of

the second

half of the 20th century.

Since then, Harry has foolishly agreed to

appear on various panels and platforms with me in tow, at conventions

and

conferences. He was even my editor for the annual anthology of the

Crime

Writers’ Association, Crime

Waves 1 in 1991, though if

there was a Crime Waves 2 I was not

invited to contribute and we were asked to work together by The Times in 2000 to produced a

definitive list of the 100 Best Mysteries of the 20th

century, which

we did with a

surprising amount of

instant agreement, some intelligent debate, a small amount of

horse-trading and

absolutely no resorting to fisticuffs.

I can say in all honesty that there is no

better person to appear with in a public debate if the subject is crime

fiction, for apart from his years as crime critic for The

Times (1967-1983), his books on Sherlock Holmes and Agatha

Christie, his chairmanship of the CWA (1970-71) and his presidency of

the

Detection Club (1985-2000), he is a fan

as well as an acute observer of the genre and is widely and well read.

In 1978 in Crime

Writers, a book he

edited to accompany a BBC

series, he was required to do what all reviewers hate doing:

“crystal ball

gazing” to predict the stars of the future.

He very astutely highlighted a young crime writer called

Jacqueline

Wilson, who was to turn, soon after, away from the dark side and make

her name

and fortune in children’s literature, but at the time it was,

as they say, ‘a

good spot’.

So too was Harry’s prediction that the more

sensational and gruesome murder stories ‘where the motive for

murder was

publicity’ of a new and unknown American writer (in 1978

remember) were likely

to be simply the first of a considerable

stream. The book which prompted that comment was something

called Season

of the Machete by someone called James Patterson

and I think that a

pretty fair piece of fortune telling.

It almost tempts me into making a

prediction myself, that A

Small Case for Inspector Ghote?

will not be the last we hear from the small but perfectly formed

Sherriff of

Bombay.

Mike Ripley

|