|

“I’m mad enough to

believe in romance. And I’m sick and tired of this age—tired of the miserable

little mildewed things that people racked their brains about, and wrote books

about, and called life. I wanted something more elementary and honest—battle,

murder, sudden death, with plenty of good beer and damsels in distress, and a

complete callousness about blipping the ungodly over the beezer. It mayn’t be

life as we know it, but it ought to be.”

--Leslie Charteris in a 1935

BBC radio interview sounding remarkably like Simon Templar did in The

Avenging Saint

(Hodder & Stoughton, October

1930)

“Everybody knows the sign of

the Saint” according to the advertising slogan printed on hundreds of thousands

of literary Saint adventures from the 1930s onwards and it is a maxim that holds

strong in the 21st century.

Admittedly some younger

generations may struggle to reconcile the somewhat tepid impersonation by Val

Kilmer with the debonair adventurer that their parents or grandparents tell them

about, but nevertheless memories of the Saint, and recognition of the Saint’s

stick-man icon, remain strong despite such latter-day disappointments.

This is undoubtedly due in a

large part to the Saint being perhaps the world’s first truly multi-media hero;

fifteen feature films, three TV series to date (for the purposes of this article

we shall charitably forget the failed TV pilot starring Andrew Clarke), 11 radio

series and a comic strip that was syndicated in newspapers around the world for

more than a decade all sprung from the original 36 Charterisian Saint

adventures. Add to that the subsequent 13 collaborative books and the 40

adventures published in French and Dutch but not in English and you get a

mind-boggling and sometimes confusing curriculum vitae.

But amidst all that

adventure and adaptation who is the real Saint?

“To me he is tremendously

personal, and yet in a way he is as impersonal as any character can be, because

more than anything else he is only an attitude of mind.”

Charteris in that radio

interview again

Simon Templar first appeared

in a 1928 novel entitled Meet-The Tiger! written by 21 year old author

Leslie Charteris.

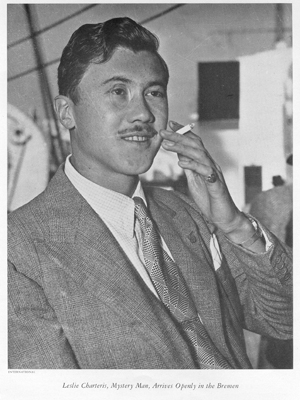

Charteris, born Leslie

Charles Bowyer-Yin, had wanted to be a writer since his formative years in

Singapore. With a Chinese father and an English mother in the British Crown

Colony young Leslie found it hard to make friends; the English children had been

told not to play with Eurasians and the Chinese children had been told not to

play with the Europeans. Leslie was caught in between and took refuge in

reading. He’d read the family collection of encyclopaedias from start to finish,

not realising that for most people education was a chore.

And he loved a magazine

called Chums; "The Best and Brightest Paper for Boys" (if you believe the

adverts) was a monthly periodical paper that was full of swashbuckling adventure

stories aimed at boys and encouraging them to be honourable and moral and

perhaps even "upright citizens with furled umbrellas".

Undoubtedly these stories would influence his later work…

When his parents split up,

shortly after the end of World War 1, he accompanied his mother and brother back

to England, where he was sent to Rossall School, in Fleetwood, Lancashire.

Rosall was, and still is, an English Public School, very much in line with the

stereotype, and struggled to cope with this multi-lingual mixed race boy, just

into his teens, who’d already seen more of the world than many of his peers

would see in their lifetime. He was an outsider.

Determined to pursue a

creative career he decided to study art so went to Paris—after all, that was

where all the great artists went—but soon found that the life of a literally

starving artist didn’t appeal and as a result of parental pressure, returned to

England and started studying for a law degree at Cambridge University.

In the mid-1920s Cambridge

was full of Bright Young Things—aristocrats and bohemians somewhat typified in

the Evelyn Waugh novel Vile Bodies—and again the mixed race Bowyer-Yin

found that he didn’t fit in. He was an outsider who preferred to make his way in

the world and wasn’t one of the privileged upper-class. It didn’t help that he

found his studies boring, and decided it was more fun contemplating ways to

circumvent the law. This inspired him to write a novel and when publishers Ward

Lock & Co. offered him a three book deal on the strength of this he abandoned

his studies to pursue a writing career instead.

X Esquire,

his first novel, appeared in April 1927. The story is about a man, X Esquire,

who is assassinating businessmen who want to wipe out Britain by distributing

quantities of free poisoned cigarettes. His second novel, The White Rider,

was published the following Spring and has the hero chasing the UnGodly to

rescue his damsel in distress only for him to overtake the villains, leap into

their car…and promptly faint.

These two plot highlights

may go someway to explaining Charteris’ comment on Meet the Tiger, which

was published on September 10th of that same year, “It was only

the third book I’d written, and the best I would say for it was that the first

two were even worse”.

Twenty-one year old authors

are naturally self-critical and despite reasonably good reviews, when the Saint

didn’t set the world on fire, Charteris moved on to another hero for his next

book.

That was The Bandit

an adventure story featuring Ramon Francisco De Castilla y Espronceda Manrique

which Ward Lock published in the summer of 1929 shortly after it had been

serialised in the Empire News, a now long-forgotten Sunday newspaper. But

sales of The Bandit were less than impressive and Charteris’

scribaciousness was taking a bashing; it was all very well writing but if nobody

wants to read what you write, what’s the point?

"I had to

succeed, because before me loomed the only alternative, the dreadful penalty of

failure...the routine office hours, the five-day week...the lethal assimilation

into the ranks of honest, hard-working, conformist, God-fearing pillars of the

community".

In late 1928 Leslie met

Monty Haydon, a London based editor who was looking for writers to pen stories

for his new paper, Thriller—The Paper of a Thousand Thrills,

“He said he was starting

a new magazine, had read one of my books and would like some stories from me. I

couldn’t have been more grateful, both from the point of view of vanity and

finance!”

It launched in early 1929

and Leslie debuted in issue no.4 (dated March 2nd, 1929) with The

Story of a Dead Man featuring Jimmy Traill. That was followed up just over a

month later with The Secret of Beacon Inn featuring Ramses ‘Pip’ Smith.

At the same time Leslie finished up writing a non-Saint novel, Daredevil,

which featured Storm Arden as the hero and debuted a Scotland Yard Inspector by

the name of Claud Eustace Teal.

The return of the Saint was

in the thirteenth edition of The Thriller, "A Thrilling Complete Story of

the Underworld" the byline proclaimed, it was titled The Five Kings and

actually featured Four Kings and a Joker. Simon Templar, of course, was the

Joker.

Charteris spent the rest of

1929, and five subsequent Thriller stories, telling of the adventures of

the Five Kings ”

"It was very hard work,

for the pay was lousy, but Monty Haydon was a brilliant and stimulating editor,

full of ideas. While he didn’t actually help shape the Saint as a character, he

did suggest story lines. He would take me out to lunch and say, “What are you

going to write about next?” I’d often say I was damned if I knew. And Monty

would say, “Well I was reading something the other day...” He had a fund of

ideas and we would talk them over, and then I would go away and write a story.

He was a great creative editor."3

He would have one more go at

writing about a hero other than Simon Templar, using three novelettes that were

published in Thriller in early 1930, but returned to the Saint, partly

due to his self-confessed laziness—he wanted to write more stories for

Thriller and other magazines, and creating a new hero for every story was

hard work—but mainly due to feedback from Monty Haydon. It seemed people wanted

to read more adventures of the Saint…

Charteris would contribute

over 40 stories to The Thriller throughout the 1930s. Shortly after their

debut Charteris persuaded publisher Hodder & Stoughton that if he collected up

some of these stories, rewrote them a little, then they could publish them as a

Saint book. They tried this with Enter the Saint, which was first

published in August 1930, and the reaction was good enough for them to try it

again. And again…

Of the 20 Saint books

published in the 1930s, almost all of them have their origins in those magazine

stories.

Why was the Saint so popular

throughout the decade? Aside from the charm and ability of Charteris’

storytelling the stories, particular those published in the first half of the

30s, are full of energy and joie de vivre. And with economic depression rampant

throughout the period, the public at large seemed to want some escapism.

Also his appeal was

wide-ranging; he wasn’t an upper-class hero like so many of the period; with no

obvious background and no adherement to the Old School Tie, no friends in high

places who could provide a Get Out of Jail Free card, the Saint was uniquely

classless.

Not unlike his creator.

Throughout his formative

years Leslie suffered, unjustly, from his mixed race; whether in his early days

in Singapore, at an English Public School, at Cambridge University or even just

in everyday life, he couldn’t avoid the fact that for many people his mixed

parentage was a problem – he would later tell the story of how he was chased up

the road by a stick-waving Typical English Gent who took offence to his daughter

being escorted around town by a foreigner.

Like the Saint he was an

outsider.

Although he had spent a

significant portion of his formative years in England Leslie couldn’t settle.

As a young boy he read of an

America “peopled largely by Indians, and characters in fringed buckskin jackets

who fought nobly against them. I spent a great deal of time day-dreaming about a

visit to this prodigious and exciting country”

Inspired by Doubleday, who

had published several of his novels, Charteris and his wife set sail for the

States in late 1932. Pretty soon they were in New York experiencing the tail-end

of Prohibition.

Times were tough though, and

despite sales to American magazine and others, it took a chance meeting

with writer-turned Hollywood Executive Bartlett McCormack in their favourite

speakeasy for Charteris’ career to step up a gear.

Soon Charteris was in

Hollywood, writing for Paramount Pictures. However Hollywood’s treatment of

writers wasn’t to Charteris’ taste and soon he began to yearn for home. He soon

returned back to the UK and began writing more Saint stories for Monty Haydon

and Bill McElroy.

He also rewrote a story he’d

sketched out whilst in the States, and indeed a version of it had been published

in American magazine in September 1934. The Saint in New York,

which Hodders published in 1935, was a step-up for the Saint and Leslie

Charteris. Gone were the high jinks and the badinage, the youthful exuberance

evident in the Saint’s early adventures had evolved into something a little

darker, a little more hard-boiled. It was the next step in development for the

author and his creation and readers loved it; it was a bestseller on both sides

of the Atlantic.

Having spent his formative

years in places as far apart as Singapore and England, and substantial travel in

between, it should be no surprise that the Leslie had a serious case of

wanderlust, and with a bestseller under his belt had had the means to see more

of the world.

1936 found him

in Tenerife, not only researching another Saint adventure, but also translating

the biography of Juan Belmonte, a well-known Spanish matador. In 1937, he

divorced his first wife, but married again in early 1938. Charteris and his new

bride set off in a trailer of his own design and spent eighteen months

travelling round America and Canada.

It was The

Saint in New York that reminded Hollywood of Charteris’ talents and film

rights to the novel were sold prior to publication in 1935. Although the

proposed 1935 film production was gunned down by the Hays Office for its violent

content, it was RKO’s eventual 1938 production that persuaded Charteris to try

his luck once more in Hollywood.

New

opportunities had opened up. Throughout the 1940's The Saint appeared not only

in books and movies, but in a newspaper strip, a comic book series and on radio.

Anyone wishing

to adapt his character in any medium was to find a stern taskmaster in

Charteris. He was never completely satisfied, nor was he shy of showing his

displeasure. Charteris did, however, ensure that copyright in any Saint

adventure belonged to him, even if scripted by another writer, a contractual

obligation that he was to insist on throughout his career.

Charteris was

soon spread thin, overseeing movies, comics, newspapers and radio versions of

his creation, and this, along with his self-proclaimed laziness, meant that

Saint books were becoming fewer and further between; the Saint was becoming an

industry and Charteris couldn't keep up. In 1941 he indulged himself in a spot

of fun by playing The Saint -- complete with monocle and moustache -- over six

pages of a photostory in Life magazine.

In July 1944

he started collaborating under a pseudonym on Sherlock Holmes radio scripts,

subsequently writing more adventures for Holmes than Conan Doyle. Not all his

ventures were successful -- a screenplay he was hired to write for Deanna

Durbin, Lady On A Train, took him a year and ultimately bore little

resemblance to the finished film. In the mid-1940's Charteris successfully sued

RKO pictures for unfair competition after they launched a new series of films

starring George Sanders as a debonair crime fighter known as The Falcon.

Throughout this time Charteris' Saint novels continued to adapt to the times,

with the transatlantic Saint evolving into something of a private operator,

working for the mysterious Hamilton and becoming, not unlike his creator, a

world traveller, finding that adventure would seek him out rather than vice

versa.

Charteris

maintained his love of travel and was soon to be found sailing round the West

Indies with his good friend Gregory Peck. His forays abroad gave him ever more

material and he began to write true crime articles as well as an occasional

column in Gourmet magazine.

By the early

50's Charteris himself was feeling strained. With three failed marriages behind

him, he roamed the globe restlessly, rarely in one place for longer than a

couple of months. He continued to maintain a firm grip on the exploitation of

The Saint in various media, but was writing little himself.

Charteris

began thinking seriously about an early retirement.

Then, in 1951,

he met a young actress called Audrey Long, when they became next door neighbours

in Hollywood. Within a year they had married, a union that was to last the rest

of Leslie's life.

Leslie and Audrey pose for a

beer advert

He attacked

life with a new vitality. They travelled -- Nassau became a favoured escape --

and he wrote. He struck an agreement with the New York Herald Tribune for

a Saint comic strip which would appear daily and be written by Charteris

himself. The strip ran for thirteen years with Charteris sending in his

hand-written storylines from wherever he happened to be, relying on mail

services around the world to continue the Saint's adventures. New Saint novels

began to appear and Charteris reached a height of productivity not seen since

his days as a struggling author trying to establish himself. As Leslie and

Audrey travelled, so did the Saint, visiting locations just after his creator

had been there.

By 1953 The

Saint had already enjoyed twenty-five years of success, and The Saint

Magazine was launched. Charteris had become adept at exploiting his creation

to the full, mixing new stories with repackaged older stories, sometimes

rewritten, sometimes mixed up in 'new' anthologies, sometimes adapted from radio

scripts previously written by other writers.

Charteris had

been approached several times over the years for television rights in The Saint;

he expended much time and effort throughout the 1950s in trying to get the Saint

on TV, even going so far as to write sample scripts himself, but it wasn’t to

be. He finally agreed a deal in autumn 1961 with English film producers Robert

S. Baker and Monty Berman. The first episode of The Saint television

series, starring Roger Moore, went into production in June 1962. The series was

an immediate success, though Charteris had his reservations. It reached second

place in the ratings, but Charteris commented that "in that distinction it

was topped by wrestling, which only suggested to me that the competition may not

have been so hot; but producers are generally cast in a less modest mould".

He resented the implication that the TV series had finally made a success of The

Saint after 25 years of literary obscurity.

Throughout the

run of the series Charteris was not shy about voicing his criticisms both in

public and in a constant stream of memos to the producers. "Regular

followers of the Saint Saga…must have noticed that I am almost incapable of

simply writing a story and shutting up."

Nor was he shy about exploiting this new market by agreeing a series of tie-in

novelisations ghosted by other writers, which he would then rewrite before

publication.

Charteris

mellowed as the series developed and found elements to praise also. A close

friendship developed with producer Robert S. Baker and would last until

Charteris' death.

In the early

sixties, on one of their frequent trips to England, Leslie and Audrey bought a

house in Surrey, and it soon became their permanent base. He explored the

possibility of a Saint musical and began writing some of it himself.

Charteris no

longer needed to work. In his sixties by now, he supervised from a distance

whilst continuing to travel and indulge himself. He and Audrey made seasonal

excursions to Ireland and the South of France, where they kept residences. He

began to write poetry and devised a new universal sign language, Paleneo, based

on notes and icons used in his diaries. With the release of Paleneo he decided

enough was enough and announced, again, his retirement. This time he meant it.

The Saint

continued regardless -- a long-running Swedish comic strip and new novels by

ghost authors were complimented in the 1970's with Bob Baker's revival of the TV

series in Return of The Saint.

Ill-health

began to take its toll and by the early 80's, although maintaining a healthy

correspondence with the outside world, he felt unable to keep up with the

collaborative Saint books and pulled the plug on them.

Leslie took to

"trying to beat the bookies in predicting the relative speed of horses",

a hobby which resulted in several of his local betting shops refusing to take

'predictions' from him as he was too successful for their liking.

He still

received requests to publish his work abroad but became completely cynical

towards further attempts to revive The Saint. A new Saint Magazine only lasted

three issues, and D.L. Taffner's productions of The Saint In Manhattan

with Tom Selleck look-alike Andrew Clarke, and The Saint with Simon

Dutton left him bitterly disappointed. "I fully expect this series to lay

eggs everywhere…the old joke about crying all the way to the bank is my only

consolation".

Hollywood

producers Robert Evans and Bill Macdonald approached him and made a deal for The

Saint to return to cinema screens. Charteris still took great care of The

Saint's reputation and wrote an outline entitled The Return of The Saint --

an older Saint would meet the son he didn't know he had.

Much of his

last year was taken up with the movie. Several scripts were submitted to him --

each moving further and further away from Charteris' concept -- but this

screenwriter from 1940's Hollywood was disheartened with the Hollywood of the

90's. "...there is still no plot, no real story, no characterisations, no

personal interaction, nothing but endless frantic violence...". Besides,

with producer Bill Macdonald hitting the headlines for the most unSaintly

reasons, he was to add, "How can Bill Macdonald concentrate on my Saint movie

when he has Sharon Stone in his bed?"

The Crime

Writers' Association of Great Britain presented Leslie with a Lifetime

Achievement award in 1992 in a special ceremony at the House of Lords. Never one

for associations and awards, and although in visible ill-health, Leslie accepted

the award with grace and humour ("I am now only waiting to be carbon-dated").

Although suffering a slight stroke in his final weeks, Charteris still dined out

locally with family and friends, before finally passing away at the age of 85 on

April 15th 1993.

His death

severed one of the final links with the classic thriller genre of the 1930's and

1940's, but he left behind a legacy over nearly one hundred books, countless

short stories, and TV, film, radio and comic-strip adaptations of his work which

will endure for generations to come.

“I have never been able to

see why a fictional character should not grow up, mature, and develop, the same

as anyone else. The same, if you like, as his biographer. The only adequate

reason is that—so far as I know—no other fictional character in modern times has

survived a sufficient number of years for these changes to be clearly

observable. I must confess that a lot of my own selfish pleasure in the Saint

has been in watching him grow up.”

“I was always sure that

there was a solid place in escape literature for a rambunctious adventurer such

as I dreamed up in my youth, who really believed in the old-fashioned romantic

ideals and was prepared to lay everything on the line to bring them to life. A

joyous exuberance that could not find its fulfillment in pinball machines and

pot. I had what may now seem a mad desire to spread the belief that there were

worse, and wickeder, nut cases than Don Quixote.

Even now, half a

century later, when I should be old enough to know better, I still cling to that

belief. That there will always be a public for the old-style hero, who had a

clear idea of justice, and a more than technical approach to love, and the

ability to have some fun with his crusades.”

|