|

Appreciations

THE IPCRESS FILE

It’s

hard to realize today what an impact Len

Deighton’s remarkable spy novel had on its first appearance

in the 1960s. Like

le Carré, Deighton was reacting against the glossy,

unrealistic depiction of

espionage in the novels of Ian Fleming (a certain Puritanism was a

factor at

the time, less à propos these days, now

that Fleming’s considerable

virtues have been recognized). But certainly The Ipcress File,

with its

insolent working-class hero and low-key treatment of all the quotidian

details

of a spy's life (endless futile requisitions for petty cash, a

decidedly

unglamorous secret service HQ) was astonishingly fresh, while the

first-person

narrative was a sardonic Londoner’s refraction of Chandler’s

Marlowe-speak two decades on. Another radical

touch was the refusal to neatly tie up the narrative with a cathartic

death for

the villain – the shadowy opponent of Deighton’s

unnamed protagonist is – for

political reasons – unpunished. A series of novels in the

same vein followed,

none quite as impressive as this debut – but all highly

accomplished.

- Barry Forshaw,

editor of British Crime Writing Encyclopedia

This

is something Michael Caine agrees with me

about. Or perhaps it’s the other way around. Either way, we

both regret that

Deighton’s An Expensive Place To

Die was (like companion volume Horse Under Water) never made into a

Harry Palmer film. But then again, maybe it is just as well. It is

impossible

to summarise the plot in that two-sentence pitch Hollywood

still loves (“It’s Goldfinger Meets Raymond Blanc

at The Priory”), so getting a

workable script would have been a nightmare. Remember, legend has it

that if

any friend told Deighton they could follow the plot of The

Ipcress File, he would jumble it up some

more. Deighton put the storyline of AEPD

into a Moulinex and left it to

run. There is a

shady artist, explosive

dossiers, double-double- crosses, institutionalised voyeurism and

Chinese

nuclear weapons. It doesn’t

matter

because the book is a love letter to two things: the

(brilliantly rendered) exoticism of Paris

in

the sixties and a certain anonymous

English spy, described as ‘truculent and cynical’

on my book flap,

but also whip-smart and unflappable.

Reading it, you can well see why a young Michael Caine imagined himself

walking

off the page. The character that the movies christened ‘Harry

Palmer’ became

synonymous with Swinging London and Cold War Berlin,

but this Deighton reeks of garlic, Gauloise and cuisine faite

par le patron,

as well as governmental

treachery. My copy may have the

one of the worst jackets of all time, in which the hero is rendered,

alarmingly, as a Mr. Bean look-a-like, but in many ways the book

hasn’t dated

at all. All you have to do is change the E-Type to an XF, give him a

mobile

phone and the world-weary, put-up, suspicious secret agent would fit

nicely

into the world of Spooks. And Paris

is

still an Expensive Place To Die.

-

Robert

Ryan author of Empire of Sand and Underdogs

Len

Deighton added a change of direction in

espionage fiction from the glamour and excesses of Ian

Fleming’s James Bond,

into the downbeat reality of life behind the looking glass with his

cynical

anti-hero Harry Palmer. The Palmer novels were of course The

Ipcress File

[1962], Horse Under Water [1963], Funeral

in Berlin [1964], Billion

Dollar Brain [1966], A Expensive Place to Die

[1967], Spy Story

[1974] and Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy [1976] US

title Catch a

Falling Spy. Incidentally as they all feature first person

narration; the

protagonist Harry Palmer is never actually named and in fact in the

last two

novels, Deighton stated that the protagonist [Patrick Armstrong] is a

different

character than in the preceding four.

It

was the film versions that gave the anti-hero

his name. For many readers however, Harry Palmer would be the

antithesis of Ian

Fleming’s James Bond, especially when one compares the actors

who played James

Bond at the time. Sean Connery’s James Bond, compared to

Micheal Caine’s Harry

Palmer was a polar opposite. Coincidentally

Bond producer Harry Saltzman was also involved with the Harry Palmer

films. The

protagonist in these novels [Harry Palmer] is a Grammar school boy

working for

Public school boys, and cynical toward the world he sees around him,

they are

required reading for anyone with interests in British espionage fiction

of that

period.

My

personal favourite of the Palmer novels is of

course The Ipcress File [1962], because it was the

first Deighton novel

that passed my table; but also its blue collar hero’s insight

is delightful.

The tale reveals that the hunt for a missing scientist is linked to a

large

scale conspiracy that only the working class hero can solve.

–

Ali

Karim assistant Editor of archive.shotsmag.co.uk

CLOSE UP

Most of the

best writers are versatile. While they may

achieve fame through one particular novel, or type of novel, they are

likely to

have the breadth of mind, and talent, to turn their hand to a wide

range of

different subjects. Len Deighton will always be associated with the spy

novel,

and I have long been a fan of books like Bilion

Dollar Brain and Horse Under Water.

But

I admire some of his other work just as much. I’m not

qualified to judge his

cookery books, or his travel guides, but I enjoyed Only

When I Larf, and, perhaps even more, the routinely overlooked

Close-Up.

Close-Up was published

in 1972, and I read it a

couple of years later. It’s set in the film world and

presents the story of a

fading star called Marshall Stone. Deighton spent some time working in

the

movie business, and he put his experience of the business to good use.

The gap

between image and reality is convincingly portrayed. Above all, the

material

offers tremendous scope for Deighton’s sardonic humour. Not

least right at the

end when the mogul Koolman says: ‘Close-Up.

I’d never buy a title like that. It’ll mean nothing

on a marquee in Omaha.’.

- Martin

Edwards, crime writer and legal expert

I

first met Len Deighton in the Mucky Duck (aka The

White Swan, the Daily Mail pub off Fleet Street)

when The Ipcress File had just hit

the best-seller lists. He

couldn't

believe his luck. Up to then he'd been known - if at all - as a cookery

writer

in national papers. Nice bloke, he seemed then.

As

for the films,

I think they worked very well.

Caine was particularly good as Harry Palmer (not that

Deighton ever gave

his hero a name). Billion

Dollar

Brain was the least impressive of the movies but then it was

extremely

complicated and by that time there was a lot of Hollywood

money involved (to say nothing of the eccentric Ken Russell) and

everything

became too overblown.

Personally

- though I very much took to the guy - I

wasn't all that happy with Deighton.

At

the time I'd just written my first spy novel, The Matter of

Mandrake,

rather in the James Bond genre, and I wasn't too chuffed about some

bloke coming

along and moving the whole business from upper and middle to the

working

class. But his were

bloody good books

and I still enjoy the films.

- Barry Norman, thriller writer and film critic.

I

well remember the first time I met Len. He had

come to a meeting of the Crime Writers Association with a view to

joining;

somehow or another we began talking. The meeting came to an end and Len

said to

me "Come and have a

meal

somewhere". We went to a nearby Chinese where the waiter had some

difficulty using both serving spoon and fork in the one hand. Len

looked up at

him and said simply: "It's difficult, isn't it? I used to have the same

trouble when I was an aircraft steward".

Awkward

situation vanishing in an airy puff of smoke. And I thought What a simply nice man he

is. A belief I

have kept to this day.

- H.R.F.

Keating creator of the Inspector Ghote crime series

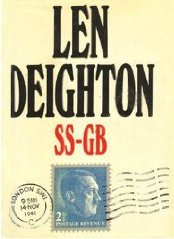

SS-GB

SS-GB is

a remarkable crime novel, set in 1941 London, but in an England which has lost

the war and is occupied by

the Nazis and from the opening line of dialogue –

“Himmler’s got the King

locked up in the Tower of London”

– you know you are in classic Deighton

territory.

The

plot revolves around the murder of a scientist in a seedy back room in

Shepherd’s Market and the detective work of the upright and

honourable Douglas

Archer (“of the Yard”), one of the Metropolitan

Police’s top cops. Archer has a

shrewd idea “whodunit” almost from the off, but

that’s not the point, for the

murder turns out to be only the tip of a serpentine trail of espionage,

double-crossing and triple-crossing which involves atomic research, the

fate of

the imprisoned King George VI, the neutrality of the United States and,

of

course (this being the author of The

Ipcress File) the deadly rivalry between various intelligence

agencies as

to who will be top dog.

There

are

some marvellous set pieces: the chilling raid by the SS on the school

of the

widowed Archer’s son, the surreal escape of the King from the

Tower which

results in him being pushed in a wheelchair through fog-bound London,

the

blowing up of Karl Marx’s grave in Highgate Cemetery during a

celebration of

Nazi-Soviet relations and the sinister, quite chilling, appearance of a

face at

a train window which turns out to belong to Heinrich Himmler.

But

the

dark heart of the story is what Deighton does best: the internecine

warfare

between protagonists supposedly on the same side. In SS-GB,

the power struggle is between the seemingly jovial

Gruppenfuhrer Kellerman of the SS and Standartenfuhrer Huth of the SD

(the SS’s

intelligence service), which reprises the scenario of Dalby and Ross

always

jostling for position in The Ipcress File.

In all such battles, of course, there is collateral damage which drives

the

tension and allows amasterful author to make some crucial observations

of human

nature.

Critics

of

the book may say it is simply The Ipcress

File re-written as imaginary history. Well if it is, so what?

Just

sit

back and marvel at the imagination it took to do it.

- Mike Ripley creator of the

Angel crime series and keen archaeologist

BOMBER

I came to

Deighton as a result of Ipcress File,

which is certainly an excellent book and film, but

for me his greatest work has to be Bomber.

It is a magnificent anti-war work, and shows the courage of the young

bombers

without glorifying their work. Rather, by looking at the victims of the

bombing

run, it shows the futility of their actions.

The story

itself looks at the final raid of

a Lancaster. Pilot Sam

Lambert has made it from the

beginning of the war to this point, and although he’s

suffering from exhaustion

and nervous strain, his crew revere him. They count on him as their

talisman.

But the pathfinder Mosquito is shot apart and her load of incendiaries,

designed to mark out a city (Krefeld) instead falls

short, and the whole

exercise is set to drop on a small town, Altgarten.

More recently

there have been explanations of the full

horror of towns which were bombed in this way. Deighton describes in

precise,

clinical detail how the multiple fires lead to a firestorm, and what

that means

for the poor inhabitants.

And that is his

great skill. This story is

not one person’s tale. It is a set of interlinked lives, and

he looks at the

attack from all points of view. It is this which gives the story its

enormous

power. And, of course, its horror.

I’d

recommend the book to anyone.

-Mike

Jecks

hailed as the master of the medieval murder mystery

FUNERAL IN BERLIN

It’s

iniquitous to have to pick out one of

Deighton’s many masterpieces but if I’ve got to it

has to be Funeral in Berlin.

Deighton’s

take on spies and the Cold War always seemed more realistic to me than

that of

his rivals. He didn’t go for the fake glamour of Fleming.

This was espionage as

it ought to be if you think about it: rough, raw, cold and inhuman. Funeral

in Berlin magnifies this sense of the ‘great

game’ by putting chess at the

heart of the book, with a quotation about the game fronting every

chapter.

The

Russian Colonel Stok boasts about being one of

the best chess players and asks the anonymous British hero whether he

liked the

game too. Our man (who is not, as any Deighton fan knows, called Harry

Palmer),

replies, ‘Yes, but I prefer games where there is a better

chance to cheat.’

Which

makes him the better spy, naturally. Deighton

as his best was unique, an original who could handle character and plot

with

extraordinary aplomb, and make places like Berlin,

torn apart by the Wall, seem as real as any grotty London

suburb. One of the 20th century greats.

- David Hewson author of the

Nic Costa thrillers

BILLION DOLLAR BRAIN

I first made

the acquaintance of Len Deighton over

forty years ago when we spent a rainy weekend in a caravan on the Devon coast. Someone

had left behind copies of The Ipcress File,

Horse Under Water and

Funeral

in Berlin. I was

captivated by them and have been a

devoted fan of Deighton’s work ever since. He really

qualifies as a member of

the Magic Circle because his

spy novels find new conjuring tricks every time. Of the

other books, Bomber is my

favourite.

But if I got stuck in a caravan during a storm again, the novel

I’d prefer to

re-read would be Billion Dollar Brain.

It’s fast, funny, idiosyncratic, unashamedly corny and it

contains just enough

information about the subjects on which it touches to give the

impression that

the author is an expert on each one. Only a master storyteller can do

that.

- Keith Miles aka Edward

Marston

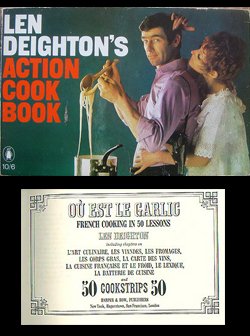

LEN DEIGHTON’S COOKBOOKS

Whenever I make

an omelette, I think of Len Deighton.

A couple of years ago, the BBC screened a documentary in which the

great man

revealed that he always adds a tiny splash of water to a bowl of

freshly

cracked eggs. Ever the scientist, Deighton had learned that the shell

of an egg

is porous; water vapour is apparently escaping through it all the time.

Before

cooking, the discerning chef should always restore the egg’s

molecular

structure with a tiny amount of water.

Does it work?

Don’t ask me. But plenty of

Deighton’s other cooking tips, culled from his culinary

classics Ou Est Le Garlic? and Len Deighton’s Action Cook Book, have served me well for many

years. Did you know, for example, that if you’re putting oil

and vinegar onto a

salad, you should always put the vinegar on first, otherwise the oil

creates a

coating on the lettuce upon which the vinegar will be unable to obtain

a grip?

Len taught me that.

If

I’m making Deighton sound overly

fastidious, I don’t mean to. When it comes to cooking, he is

a man of immense

learning, but also one determined to take the mystery out of the

process of

turning raw ingredients into simple, delicious meals. Deighton was, for

a time,

The Observer’s cookery writer, the Nigel Slater of the

Swinging Sixties, and

every week would draw a simple cartoon strip to illustrate the

stage-by-stage

process of preparing a particular dish. These strips are reproduced in Ou Est Le Garlic? and the Action

Cook Book. They show the amateur

cook how to prepare everything from a simple chicken stock to Coquilles

St

Jacques, from a hollandaise sauce to Osso Buco. Legend has it that one

of the

strips is hanging in Michael Caine’s kitchen in the film of The Ipcress File.

There is no

doubt that the books, which

were published in the mid-1960s, were intended partly to cash in on the

huge

success of Deighton’s early novels. The Action

Cook Book, in particular, was marketed at trendy British

bachelors who

wanted to act like Harry Palmer but froze in terror at the sight of a

potato.

The cover of my copy shows a woman in a negligée running her

fingers through

the hair of a square-jawed brute busily tossing a pan of spaghetti

while

winking at the camera. The implication is clear. Learn how to stuff a

Chicken

Kiev properly, lads, and you’ll have her clothes off in no

time.

But these are

serious cookbooks. I wouldn’t

trade mine for any of the so-called modern classics by Gordon and Jamie

and

Nigella. Long before Heston Blumenthal came along with his egg and

bacon ice

cream and his canister of liquid nitrogen, the young Len Deighton was

schooling

himself in the science of French cuisine. There’s very little

the author of Billion Dollar Brain

doesn’t know about

the boiling point of clarified butter or the impact of heat on a shin

of veal.

But he doesn’t make you feel bad for your culinary ignorance.

Quite the

opposite, in fact. The books are chatty and low key, with that lovely

dry wit

which characterises the novels. Here is Deighton on vinaigrettes:

“American

cooks add half a dozen more

garnishes to salad dressing, including lemon peel, chopped cheese,

curry

powder, ketchup and, even more terrible, sugar. I give you this

information to

demonstrate the depths of depravity to which it is possible to

sink.”

Of course, being forty years old,

certain elements in the books are out-of-date. There’s a bit

too much stuff

involving aspic, and a recipe for tripe and onions which should be

consigned to

a time capsule. Rumour has it that an enterprising editor at Harper

Perennial

has hit on the idea of repackaging the cookbooks for a 21st

century

audience. I certainly hope that’s true, and I certainly hope

that the all-new

versions won’t excise these anachronistic details. They are

part of the books’

charm. In my view, Ou Est Le Garlic?

and Len Deighton’s Action Cook Book

are classics of British cuisine, and every bit as central to

Deighton’s

reputation as Harry Palmer, Bomber,

and Hook Line and Sinker.

-Charles Cumming, author of TYPHOON

Okay,

I’ll come clean. I’m a great fan of all Len

Deighton’s work, but my favourite thriller is his Action Cookbook (and its companion Où est le Garlic?). For over

forty years, and decades before it

became top of the pops at UK restaurants,

his crème

brûlée has thrilled my family and

friends. In my single days

in the 1960s these two cookbooks were both full of information and of

such

delights as garlic mayonnaise, Baked Alaska, cheesecake, mousses,

pommes de

terre Dauphinoise, caper sauce, sabayon... All well known to us now,

but then?

Wow, how they thrilled.

Thank you, Len

Deighton, and happy

birthday. Both books are still thrilling me today.

-

Amy Myers author of

the Auguste Didier series

My main interest

in Len Deighton lies in his membership of the select band of writers

who have

imagined that World War II went the other way, and the Germans and

Japanese

won. The necessary premise almost always is that Churchill is dead by

1940 or

1941 – Deighton has him killed by Himmler, the royal family

imprisoned and the

SS in Whitehall.

It’s a long time since I read SS GB

(published 1978) but I seem to remember that he sticks to the immediate

period

of his alternative history. The other hands set their stories well into

the

aftermath of the war. Fatherland (Robert Harris) is

evidently taking

place in the Sixties, with a nice little aside to the Beatles launching

their

career in Hamburg just as they

did in ‘real’ history. Giles

Cooper’s disturbing TV play The Other Man

went out in 1964

as a contemporary yarn of an upright British army officer doing the

Nazis’

bidding in a protracted racial war in Asia. Inside every

decent man, Cooper was suggesting, is

this ‘other man’ waiting to take over.

Another television work, Philip Mackie’s three-part An

Englishman’s Castle (1978),

depended on what might be called the mirrored mirror image. Kenneth

More, as a

drama producer in the German-monitored BBC, daringly

embarks upon a soap opera of

life as it might have been if Britain had not been

subjugated. Which brings us

to the wizard of this whole genre, Philip K.Dick. The Man in

the High Castle (1960) has the

Germans ruling the Eastern

American states, the Japanese the Western, but separated by the

demilitarised

buffer zone of the Rocky Mountains. There

lives the title figure, writing his alternative history and making it

perhaps

too wishful a picture of super-power America. So Dick

flirts, just for a moment, with

an astonishing possibility. His main character, a Japanese official in San Francisco, suffers a

dizzy spell while walking in

his city, Suddenly the clean, peaceful streets are full of cars. And

ahead of

him looms a vast structure shutting out the sky and carrying yet more

automobiles. ‘What’s that?’ he mumbles to

a passing stranger. ‘Awful, ain’t it?

That’s the Embarcadero Freeway.’ Mr

Tagomi has been vouchsafed a glimpse

of the world as we have it. Though Len Deighton had shown

himself to be a

master of the trompe l’oeil when he

revealed in The Ipcress File

that the hideous foreign prison in which his hero had been tormented

was

actually in London, I

don’t think he ever risked pulling the

rug from under his own feet quite so confidently.

- Philip Purser, thriller writer and former television critic.

Horse Under Water

Horse Under Water is the odd one out among

Len Deighton's first four spy novels, and I have the feeling that it's not quite

as well known as the others. Perhaps it is because it was not filmed. Or perhaps

it is that, unlike the other three, it turns its back on the Cold War and looks

instead at the aftermath of World War Two. Of course, when Horse Under Water

was published in 1963, the war was a not so distant memory. The story is

about the attempt to recover the cargo of a U-boat sunk off the Portuguese

coast, which contains a Russian doll-like set of secrets. At first it seems to

be counterfeit money, then it turns out to be heroin - the 'horse'

of the title - and then it materialises as a compromising list

of the British high-ups who would have collaborated after a Nazi invasion. The

main villain here is a Cabinet minister and the scene where the narrator

confronts him is a little like the scenes where Bond faces Dr

No/Goldfinger/Blofeld. Except that Deighton makes it realistic. Realism is the

keynote in these books, from the footnotes to the mysterious acronyms like

W.C.O.O.(P) to the explanation of how secret information is stored. Maybe it was

all true, maybe none of it was. I suspect it's about half and half, though. No

spy writer has ever done with such cool authority.

- Philip Gooden, author of the historical Nick Revell series

|