|

In

the spring of 2006, I was asked by editor David Stuart Davies if, as

a Sherlock Holmes enthusiast, I would like to contribute a pastiche

to a collection he was intending to publish as part of Wordsworth’s

Tales of Mystery and The Supernatural series. At the

time my writing was strictly confined to contemporary crime fiction

and I wasn’t sure if I wanted to take the plunge back a hundred

years or more. Practical considerations soon took over however,

as it was my first opportunity to appear in a mass market paperback

that was being stocked by the chain bookstores. Once I decided

to do it, my long-standing interest in modern history and historical

crime fiction made the task less daunting. I’d already

devoured the Sherlock Holmes Canon, most of Poe, the Richard Hannay

quintet, Patrick O’Brian, Flashman, Captain Alatriste, the

Erast Fandorin detective stories, and the Leibermann Papers, amongst

many others.

While researching the short

story, I found a reference to the strange will of Cecil John Rhodes,

the British Empire equivalent of Bill Gates. He died in April

1902, just before the end of the Boer War, which I knew as the first

taste of modern warfare for the British Army. Although I spent

many years in South Africa, I knew very little about Rhodes, so I

turned my attention to his life and death. When I discovered

that the richest man in the Empire had a will that wasn’t just

idiosyncratic, but actually sinister, I realised I was onto something

much more substantial than the concept for a short story.

You know those Rhodes

Scholarships? Yes, well there’s actually a real-life

conspiracy theory behind them – and it sort-of happened as

well. You’ll have to read The Architect of Murder

to find out what I’m talking about. Of course, writing in

the twenty-first century, the first thing I did was Google and

Wikipedia Rhodes’ will to see if anyone else had written the

story. I found one: a science fiction novella by John Crowley

called Great Work of Time. Even though it was out of

print, I tracked down a copy and read it. It was sufficiently

different to what I had in mind, so I wrote the short story for

David, The Adventure of the Long Man, and began serious

research on the novel.

The switch from contemporary to

historical crime fiction was easier than I’d expected, and two

of the problems I’d so far had with my writing simply

disappeared.

One of the criticisms of my

work thus far was that my hardboiled approach was better suited to

American settings than the British ones with which I’m

familiar. I’d considered writing thrillers or Noir

instead, but while I enjoy both of these subgenres, my main interest

was – and still is – the murder mystery. I realised

I could get away with much more of the action and violence associated

with hardboiled detective fiction in 1902 London than 2007 London.

The Holmes stories themselves are a perfect example: often relegated

to the cosy mystery classification, they deal with mutilation, drug

abuse, kidnapping, torture, child murderers, organised crime,

assassination, and almost everything else one might expect to find in

Hammett, Chandler, Parker, and Crais. The London of The

Architect of Murder is a violent and nasty place beneath the

veneer of gentility, and when I write about the mean streets of

Westminster I’m not exaggerating: Devil’s Acre, one of

the most dangerous slums in the city, was a couple of minutes walk

from Westminster Abbey.

Another problem solved was the

possibility of real-life events catching up with, or overwhelming a

plot. To take an unrelated example, the premise for my second

novella, The Secret Service, is that al-Qaeda have

recruited Caucasian agents in order to have a better chance of

penetrating NATO security forces. The idea was suggested to me

when I read about the connection between the Stasi and the PLO

during the Cold War and – as far as I knew – hadn’t

been used before. While I was still writing the story (in

December 2005, I think), I read a report of al-Qaeda

recruiting Croatians for exactly that purpose. I finished the

novella, but I lost the originality I’d hoped to achieve.

By setting the new novel in 1902, however, the problem went away.

Not only did I know what happened next, I could actually tailor my

story to fit in with the events, and thus preserve the thread of

historical realism.

There were other benefits of

turning back the clock, which I only appreciated once I started

writing. Most importantly, I was able to tell a story while

maintaining the suspension of disbelief. To take contemporary

Britain as an example: since the reforms following murder of Stephen

Lawrence in 1993, all homicides are investigated by squads of

thirty-plus specialist detectives, and there is no way a private

detective would be allowed to conduct his or her own enquiries at the

same time. The private eye, so essential to hardboiled crime

fiction, is no longer a realistic investigator of serious crime.

Furthermore, police procedurals must now cater for huge squads of

detectives, and the author must find a convincing way of cheating, in

order to focus on a few of these individuals and tell the story in a

way that will entertain readers. Graham Hurley and Mark

Billingham do this particularly well. There are no such

concerns with historical detection. In the Edwardian period,

amateurs roamed with few constraints, and serious inquiries were

often conducted by one – or a small team of – police

detectives, especially if they were of a sensitive nature.

Another huge hurdle which

disappeared was the CSI-DNA phenomenon. I read somewhere

recently that the only way to commit a murder undetected is to cover

oneself head-to-toe in plastic and then burn the plastic afterwards,

which seems pretty accurate given the ability of crime scene

investigators to extract DNA from all sorts of trace evidence.

This is a problem for an author, unless he or she is writing a novel

with a CSI as the lead character. I find it interesting that

the detective story (including adaptations on screen) seems to have

moved from the dominance of amateurs like Dupin, Holmes, and Poirot

through the police procedural to the a new era of the scientist as

detective, ala Patricia Cornwell, Kathy Reichs, Jefferson Bass, and

of course the huge success of the CSI TV series.

Again, all of this is a problem

for an author wanting to write outside the new subgenre. How do

we keep the reader guessing without having murderers walking the

streets in plastic suits? Robert Crais and Sean Chercover have

managed to keep the traditional private eye tale alive extremely

well, but the difficulty of the task grows with every advance in what

Holmes called ‘the science of deduction’. Once

again, all these problems disappear when going back to 1902.

Crime scene and trace evidence work varied greatly across the

different police forces of the Empire, and even within police forces.

Am I saying it’s easier

to write a historical detective story?

I don’t think so. I

research all my stories, whether contemporary or historical, novel or

short story length, but there can be no doubt that historical

settings are more research intensive. Bernard Cornwell shared

his expertise and experience in an essay where he wrote that one can

never do too much research, but should only do the absolute minimum

required for a story. He was quite correct, because one could

spend years researching any historical period – and probably

enjoy every day of it – without actually writing the novel.

While I’ve made every

effort to accurately represent the place and people of 1902 London, I

am first and foremost a storyteller, telling what I hope is an

entertaining and credible tale. I also hope that readers

unfamiliar with the period will discover some interesting facts about

Edwardian England, but if they want to learn what it was like to live

there, then they’ll do better to pick up one of the excellent

non-fiction books I used for my research. The Architect of

Murder is a murder mystery which takes place in history, not a

reference book.

What I hadn’t considered

was the contentious nature of history itself. For example, I

couldn’t persuade my editor that a Scottish gentleman of the

time would refer to himself as ‘Scotch’ rather than

‘Scots’. He was convinced that the word was an

insult outside of use with regard to foodstuffs like whisky, beef,

and eggs. I had, however, taken the terminology from the work

of an Edwardian Scottish writer. Two of my proof-readers picked

up on this point as well, and I decided that my editor was right:

even though I knew the term was used at the time, the majority of

contemporary readers would see it as a mistake, or laziness on my

part. So, ‘Scotch’ became ‘Scots’.

Several emails and letters were

also exchanged over the song now best known as Land of Hope and

Glory, by Elgar and Benson. I had a different version,

called the Coronation Ode being sung by the crowds during the

coronation procession of King Edward VII (on Saturday the 9th

August 1902) and was told by a proof reader that the Coronation

Ode was first performed on the 2nd October 1902 at the

Sheffield Festival. Seeing as I’d taken my description of

the songs being sung from the diary of someone who was actually

present, I decided to argue this time. The tangle was

eventually unravelled and the song stayed. On the one hand, I

was glad that the proof reader obvious knew the period; on the other,

it seemed a lot of effort for such a minor point.

My first love is still the

hardboiled detective story, followed closely by the realistic police

procedural, but I had a hell of a time in 1902 London, and I think

the disadvantages of going back in time were outweighed by the

advantages. I enjoyed writing about real-life characters like

William Melville, who later went on to found MI5, and is considered a

possible candidate for Fleming’s ‘M’. If you

read the novel, you’ll hear ‘Q’ mentioned as well,

and there are appearances by a few of the celebrities and

personalities of the time. I won’t give any others away

because my goal is that at the end of the novel readers might want to

look up was real and who was fictional.

As an amateur historian, I like

to think of The Architect of Murder as something which could

easily have happened, something which fits perfectly with the march

of history and with the real-life events of the time. It not

only could have happened, but in a way, it did happen.

The story is about Rhodes’ will, and the eventual fruition of

that will – the scholarships – was a victory from beyond

the grave. How much of a victory? Read the book and find

out.

Editor’s note:

since Rafe submitted this article, The

Architect of Murder has sold out in

its first print run. If you would like to see it back in print,

contact Robert Hale publishers or Rafe at his website

http://www.rafemcgregor.co.uk/

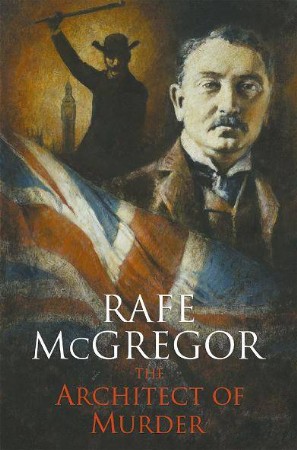

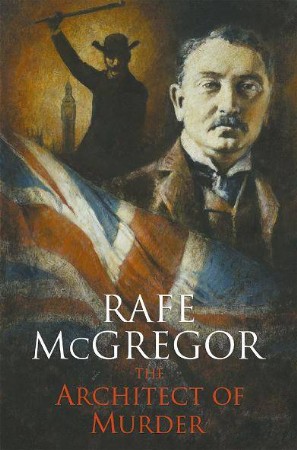

THE

ARCHITECT OF MURDER was published by

Robert Hale in February, 2009

|