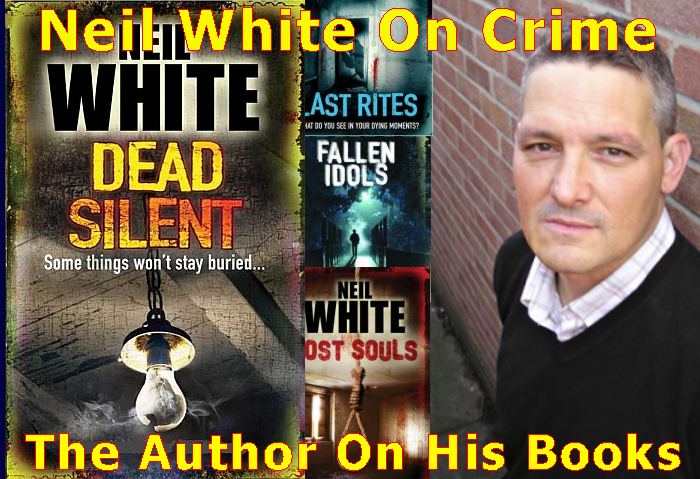

Born

above a shoe shop in the mid-1960's, Neil White spent most of his

childhood in

Wakefield in West Yorkshire as his father pursued a career in the shoe

trade.

This took Neil to Bridlington in his teens, where he failed all his

exams and

discovered that doing nothing soon turns into long-term unemployment.

Re-inventing himself, Neil returned to education in his 20's, qualified

as a

solicitor when he was 30, and now spends his days in the courtroom and

his

evenings writing crime fiction. With the publication of his latest

book, Dead Silent (Harper Collins),

SHOTS

sent Laura Harman to interrogate him.

Hi, Neil.

Without meaning to

begin in too obvious a place, how much of yourself do you find that you

put

into your characters? You have said that Jack is you, if you had more

courage –

do you wish you could be more involved in crimes the way he is?

From the start, I've always

thought of Jack Garrett as like me but less laid-back; there is lots of

me in

there. If there is a given situation, the thought process of how the

character

deals with the situation is a mix of what I think that character would

do and

how I would react if I was there and was more ballsy. The problem with

basing

it too much on myself that any piece of misfortune could well be dealt

with by

a shrug and a "them's the breaks" response.

From the start, I've always

thought of Jack Garrett as like me but less laid-back; there is lots of

me in

there. If there is a given situation, the thought process of how the

character

deals with the situation is a mix of what I think that character would

do and

how I would react if I was there and was more ballsy. The problem with

basing

it too much on myself that any piece of misfortune could well be dealt

with by

a shrug and a "them's the breaks" response.

In terms of being involved in crimes, I did

want to be a police officer at one point in my life, but I realised

that I was

too squeamish; I would struggle to deal with a bad road crash or a

drunk being

sick. It would be fun to get more hands-on though. I still work as a CPS

solicitor three days a week, but that is very clean and detached,

although I do

enjoy a good old bad-tempered courtroom spat now and again. The problem

I have

is that I'm a bit of a role-player, in that when I get my suit and tie

on and

go to work, I turn into someone I perhaps don't recognise, with a

different

social outlook, all about getting the bad guys. Once I get home and put

on the

scruffs, I turn back into genial old Neil again.

However, I have often thought

that if I stopped being a prosecutor, I would like to be a store

detective or

private detective, or anything really that involved lots of skulking

around and

finished off with a bit of a fight.

You came into

this career after

deciding to return to school. Do you feel more qualified to ponder upon

contemporary social problems, having experienced some of them yourself?

That's a tough one, because it's

hard to know whether I like gritty stuff because I've got a working

class

background, or I just happen to like gritty stuff. As a child, I used

to enjoy

crime programmes on television, and my father, the Johnny Cash

obsessive, was

always playing music that told gritty stories of prison life and

poverty, and none

of that was because I was on a council estate in Wakefield. It was

just what I liked and he liked (my father's father was a colliery

deputy-manager, and so had a relatively affluent upbringing, in a

large,

detached Coal Board house).

Also, the council estate I grew

up on never felt grim. Most people worked back then, there was never a

sense

that crime or drugs had a hold, and as there were not as many material

possessions in the seventies, the only real differences between

communities

were things like driveways and whether the television was black and

white or

colour.

The dole years in the eighties

were tough spiritually, and I remember what it feels like to not just

have

nothing, but also to feel that having nothing is about as good as life

is ever

going to get, but I think I was saved by youth, because as good as it

can be to

have nice things, I had some great times with friends that had little

to do

with money or status.

The dole years in the eighties

were tough spiritually, and I remember what it feels like to not just

have

nothing, but also to feel that having nothing is about as good as life

is ever

going to get, but I think I was saved by youth, because as good as it

can be to

have nice things, I had some great times with friends that had little

to do

with money or status.

The main thing I take from my

own experience is that it is all more complicated than it seems. I know

there

was never a risk of me being involved in crime, but that is more to do

with

fear of the consequences than any moral standpoint. The one thing I do

regret

is that I ended up with a chip on my shoulder, and although I like to

think

that I've shrugged it off, I am still more comfortable in a working

men’s club

than a nice restaurant. The irony is that I have learnt more about real

social

problems, like the depths of alcoholism and drug misuse that people

fall into,

through being a criminal lawyer, because I come across people who live

lives

like nothing from my own personal experience.

So I don't necessarily feel more

qualified, as I'm not sure I've "lived the life", but it doesn't feel

unfamiliar, which must help.

There is a good deal of human

interest in Dead Silent. It almost seems as though

this is as important

as the crime aspect. Would you say that anthropology is a key part of

crime and

law?

People commit crimes, and

different things drive people to act like they do. What interests me

most about

crime is what is going on in people's heads. I am always intrigued when

I see

someone in court who has done something you wouldn't expect to happen

with

their background, and so I want to know what's going through their

heads. I remember

conducting a case of a woman charged with murder, where I was the

lawyer doing

the initial hearing, and as she was brought up from the dock she

blinked at the

lights and had a general look of disbelief mixed in with fear, and I

wished I

could have sat down with her and really found out what was going

through her

mind. That's what fascinates me about crime.

But crime comes from all sectors

of society and for a whole host of reasons, and sometimes it is too

easy to

generalise about "criminals". Some people do lead criminal

lifestyles, have decided that it is the best way to provide for

themselves,

whereas others sometimes fall into it through a mix of circumstance and

bad

luck. It is always a tricky area, because in one sense poverty creates

crime, because

poverty stifles opportunities, but equally people who choose crime are

always

going to be poor, except for those who get really good at it, and the

line that

divides those who offend by choice or circumstance is too blurred to

really see

it properly.

Do you find

it hard to write

about the harsher realities of crime, or do you find that you have

become

hardened to it, for example when Laura is in peril?

Do you find

it hard to write

about the harsher realities of crime, or do you find that you have

become

hardened to it, for example when Laura is in peril?

I want to be affected by the

harsher realities of it, and that's why I like crime fiction. I want to

feel

the horror, the squeamishness, the blood, because ultimately it isn't

real, and

so I can enjoy it knowing that no one was really hurt. If I was too

hardened by

it, I don't think I would enjoy writing it, as I wouldn't enjoy reading

it. The

best example I can think of is the film Marathon Man

with Dustin

Hoffman, which involves a scene where Dustin Hoffman is "examined" by

a former death camp dentist. When the dentist finds a cavity, he rams

the metal

instrument hard into it, and it's one of those shut your eyes and

squeal

moments. The point of this example is that if you ask anyone if they

have seen

the film, they will always say "oh, is that one with the teeth", and

shudder or grimace. As a writer, I accept that my book will occupy

someone's

mind for a very short time, and the gaps will be filled by life and

books

written by other people, and so if I can ever write a book that makes

someone

go "oh, is that the book with the …" and shudder, then I

will feel

that my work is done.

Many crime heroes have their

little idiosyncrasies, whether it be a certain Belgian arrogance or a

more

earthy alcohol dependency. Jack, however, is an incredibly real

character. Did

you intentionally shy away from creating a more caricatured man?

Yes, I did. I've never been a

big fan of heroes who are incredibly heroic. I've always preferred the

ordinary

hero in an incredible situation. The danger with idiosyncrasies is that

they

can appear contrived and distracting, and only really work if they are

part of

the story. The best contemporary series characters, like Mark

Billingham's

Thorne or Rankin's Rebus, allow the idiosyncrasies to develop as the

story of

the character develops, so it is part of the character's story, rather

than

have them shoe-horned them in to make the character interesting.

Do

you ever find yourself

surprised by where your stories take you? Or do you know from the off

the exact

path you will be walking?

A bit of both really. When I

start out, I know what the story is about and how it ends, along with

some

major plot points. Joining everything together sometimes involves a

rethink, as

I realise that getting from one part of a story to another doesn't work

with my

original idea, or I might think of something better as I'm writing it.

So often

the story isn't exactly how I perceived at the start, but has the same

basic

core.

On

your website you note a

childhood love of the Famous Five. Do you think that such books can

still offer

something to the adult author (and reader) in terms of inspiration and

joy?

Just the memory of seeing a

mystery unfold in a way that is exciting and sometimes a little scary.

The best

thing about them is that the mysteries were solved by ordinary

children, not

the police or super sleuths. Okay, really posh and privileged children

who had

uncles who lived on strange islands, but the premise is the same, and

when you

are ten, you see the mystery, the excitement, not the class divide.

Are you tempted to use cases

you've been involved in as a basis for a story? Or do you try not to

use things

that might just be too real?

I don't use cases I have come

across as the basis for a story, as it just wouldn't be right. What I

do use

though are the little asides or comments you pick up on, like the slang

of the

police or comments by witnesses. What I do take from my prosecuting is

the

comfort that it is hard to be too extreme, if it can be described as a

comfort,

because real crime provides more grim realities than any writer could

think up.

Do

you enjoy the contrast

between the beautiful rolling landscape of the book and the viciousness

of the

acts committed there?

I do find middle class crime

interesting. I have dealt with a few fraud cases involving outwardly

respectable people, and it has become clear, when I have trawled

through their

bank and credit card statements, that everything was always going to

come

crashing down around them, and I have been intrigued as to how they

could live

normal lives, go to sleep, kiss the kids goodnight, smile for the

camera, with

all of that going on in the background. What goes on behind the

respectable

curtains is often more interesting than what goes on in the everyday

struggles

in the grimmer parts of town. As much as I enjoy a "grim up north"

tale, the countryside and the warmth are as much a part of the map as

the

terraced streets and derelict mills.

Finally, you

recently tweeted

that Patrick is your favourite character from Spongebob

Squarepants. Can

this really be true? I would say mine is definitely Squidward.

Patrick is by far the best

character. Preferring Squidward is like saying that you prefer Mr Burns

to

Homer Simpson. I can't believe I've been challenged on that point.

Patrick is by far the best

character. Preferring Squidward is like saying that you prefer Mr Burns

to

Homer Simpson. I can't believe I've been challenged on that point.

Visit

Neil’s website neilwhite.net

Bibliography

1. Fallen

Idols (2007)

2. Lost Souls

(2008)

3. Last Rites

(2009)

4. Dead

Silent (2010)

|