|

Some

crime writers seem to have a

fictional afterlife of their own, shifting from plotters of crimes to

solvers

of them in works created by other hands.

In

recent years Edgar Allan Poe

has been a popular choice for this treatment, popping up in Andrew

Taylor's American Boy and Louis

Bayard's Pale Blue Eye while Arthur

Conan Doyle,

not above a spot of investigation in real life, is another perennial

favourite,

whether in the BBC's "Murder Rooms" series or "Twin Peaks"

co-creator Mark Frost's "List of Seven".

Most

bizarrely, dear old Agatha

Christie is set to be paired with the BBC's favourite Time Lord in the

next

series of "Doctor Who". Now another writer from the Golden Age of

British detection is being reinvented as a sleuth.

Inverness-born

Elizabeth

Mackintosh first found fame as the playwright Gordon Daviot, but it is

as the

crime writer Josephine Tey she is best remembered today and it is

Josephine Tey

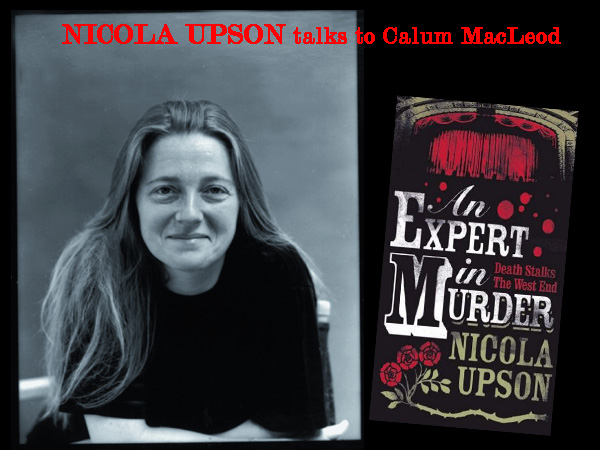

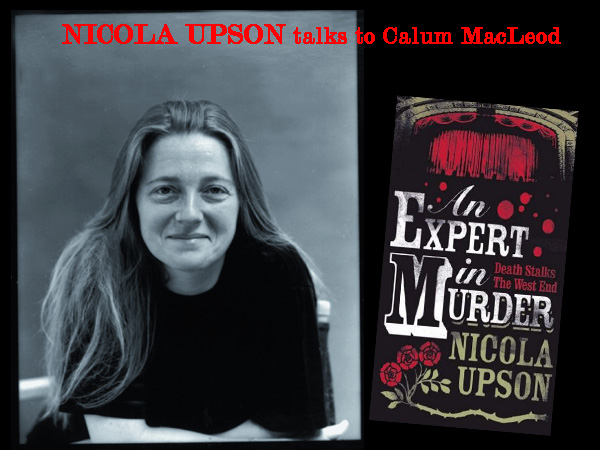

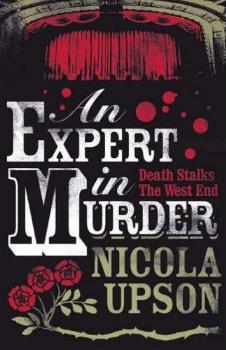

who occupies centre stage in the debut novel of journalist Nicola

Upson, An Expert in Murder.

Nicola

has long considered

placing Tey within the pages of a book, but revealed her original aim

had been

fact rather than fiction. "I suppose it must have been 15 years ago

when I

read The Franchise Affair,”

Nicola

said down the phone from her Cambridge home. "I

was always very intrigued

by that very, very thin biographical note that you got at the front of

Penguin

paperbacks. I tried to find out more about her and it just so happened

that

Virago, the publisher, had a competition for a new proposal for a new

subject

for a biography, so I did that and I got shortlisted. I did lots of

fascinating

stuff. I talked to Sir John Gielguid and lots of her colleagues who had

worked

with her around the time of her play 'Richard of Bordeaux', so I had a

fairly

comprehensive picture of her professional life, but her private life

was still

a bit of an unknown. It's become a bit clearer since then."

It

was her partner who suggested

Upson use the research in a novel and the kind of novel Tey herself is

most associated

with, the detective story. "What you've got in An

Expert in Murder and the books that will follow it, is an

entirely fictional detective puzzle, but hung on actual events in Tey's

life

and it will follow the pattern of her life as she grows older," Nicola

added.

And it is "Josephine

Tey" who is the heroine of Nicola's books, not Elizabeth Mackintosh. "I

call her Josephine Tey because, though it follows the line of Elizabeth

Mackintosh's life, the voice of the woman in these books is really the

voice of

the personality that we get in those eight crime novels: the seven she

wrote as

Tey and the one which was published as Gordon Daviot at first," Nicola

continued. "That is really how people know her, so it seemed sensible

to

call her that."

And it is "Josephine

Tey" who is the heroine of Nicola's books, not Elizabeth Mackintosh. "I

call her Josephine Tey because, though it follows the line of Elizabeth

Mackintosh's life, the voice of the woman in these books is really the

voice of

the personality that we get in those eight crime novels: the seven she

wrote as

Tey and the one which was published as Gordon Daviot at first," Nicola

continued. "That is really how people know her, so it seemed sensible

to

call her that."

She

also conceded the use of the

Tey name was a way of distancing the character of her books from the

real

author who inspired them because though they are based on real life,

they are

not designed as an accurate biography.

However,

even Tey herself was

wont to use her pseudonyms, including the male pen-name Gordon Daviot,

in her

every day life. "She was quite strict about that," Nicola commented.

"Even close friends writing to her would use the name Gordon and when

she

constructed the Josephine Tey persona, she conducted all the Tey

business as

Tey. They were very different personas which people probably thought

was a bit

odd."

And

for anyone putting their own

fictional spin on the writer's life, these different personas and the

secret

aspects of Tey's life come almost tailor made. "You know, I could hug

her!" Nicola declared. "It is a gift because it’s this

business of

gaps being more interesting than facts. The facts we have

got are

fascinating and I find it really absorbing she could carry out this

double

life, one in Scotland and one in London where she

could become a completely

different person.

"I

imagine if someone had

met her down at London when she

stayed at a club they would have found it very hard to

recognise her. She was very good at keeping the canvas blank."

If

the books are successful,

Nicola would love to follow Tey through her life up to her death in

1952. "How

obliging of her to live through such fascinating years to write about

because

the social backdrop is wonderful," Nicola said. "It’s a very

strong

period and it’s interesting to see the circles that she moved

in because that

theatre set is fascinating. It’s like a parallel Bloomsbury which was

going on at the same time,

though they never met."

In contrast with her glamorous

life with the theatre set in London was Tey's

more restricted life at home in

provincial

In contrast with her glamorous

life with the theatre set in London was Tey's

more restricted life at home in

provincial

Inverness. "She had

to come home to look after

her father on her mother's death, but it annoys me the way people

portray that

as such a sacrificial thing for her because boy did she make the most

of

it!" Nicola said. "Her Inverness life was

not as duty bound or sad as people tend to

portray it. She had a beautifully situated house and she carved out her

own

life in Inverness. There's a

wonderful letter where she

talks about how, very early on, she made a decision that she wasn't

going to

buy in to this endless round of coffees in the morning and teas in the

afternoon. People thought she was very strange to do that. and at that

time

they didn't know she wrote, so she had no right to be strange. She

didn't

involve herself in the social life of Inverness. That

wasn't just her, that was her whole family. If

you talk to people in Inverness

who knew them, they very much refer to them as a family who lived

within themselves."

Inverness. "She had

to come home to look after

her father on her mother's death, but it annoys me the way people

portray that

as such a sacrificial thing for her because boy did she make the most

of

it!" Nicola said. "Her Inverness life was

not as duty bound or sad as people tend to

portray it. She had a beautifully situated house and she carved out her

own

life in Inverness. There's a

wonderful letter where she

talks about how, very early on, she made a decision that she wasn't

going to

buy in to this endless round of coffees in the morning and teas in the

afternoon. People thought she was very strange to do that. and at that

time

they didn't know she wrote, so she had no right to be strange. She

didn't

involve herself in the social life of Inverness. That

wasn't just her, that was her whole family. If

you talk to people in Inverness

who knew them, they very much refer to them as a family who lived

within themselves."

Tey’s

decision to leave her money

to the National Trust for England, rather

than any Scottish charity’s may

have also caused some bad feeling, Nicola suggested. "Because she wrote

about England so well as

well as Scotland

it’s too often seen as: ‘Did she love England or did she

love Scotland?’

Well, I think she loved both. If you

read something like The Man in the Queue

with that wonderful bit where she’s going back to Scotland by train,

nobody could doubt how she felt

about Scotland, she loved

it."

Not

as prolific as some of her

contemporaries, Tey remains a hugely influential writer. A poll of

British

Crime Writers Association members for the 1990 Hatchards

Crime Companion"saw her 1951 novel The

Daughter of Time top the list of

greatest crime novels (The Franchise

Affair just missed out on a top 10 place, being voted in at

number 11) and

its central device of a bed bound detective solving a historical crime,

in

Tey's case the murder of the Princes in the Tower, has since been

followed by

others including Colin Dexter in The

Wench Is Dead.

Tey

has also provided material

for film and television makers. Her early novel, A

Shilling for Candles inspired Hitchcock's 1937 film Young and Innocent, her 1948 novel The Franchise Affair was filmed for the

cinema in 1950 and television in 1988 and the 1980s also saw a

television

version of her romantic thriller of impersonation and false identity, Brat Farrar.

Nicola

acknowledged that

Tey does not enjoy the public profile of her contemporaries like Agatha

Christie or Dorothy, something she attributes in part to Tey's

relatively early

death in 1952. "She is, in that horrible phrase, a writer's writer.

People

as different as P. D. James and Val McDermid, even Raymond Chandler,

have really

rated her," Nicola said. "That popular thing hasn't happened but I

hope that will change."

Nicola's

books could play a big

part in that. The publication An Expert

in Murder has led to renewed interest in Tey and her works

and in France the

publication of Nicola's book has seen

Tey's own books republished. "It's getting the people to read one,

because

she's not an acquired taste. And the people who love her really love

her,"

Nicola said.

Nicola

also regards Tey as a very

modern writer. While the popular view of Tey is of someone warm and

reassuring,

the author took a very realistic view of the effects of crime rather

than just

a murder to provide an excuse for a puzzle.

"She

did a lot to make it

possible for us to write realistic fiction," Nicola said. "I don't

think she gets the credit she deserves."

*

"An Expert in Murder"

by Nicola Upson, is published by Faber & Faber hardback

£12.99 March 2008 (978

0 571 23770 8) and trade paperback £10.99 (978 0 571 23907 8).

|