|

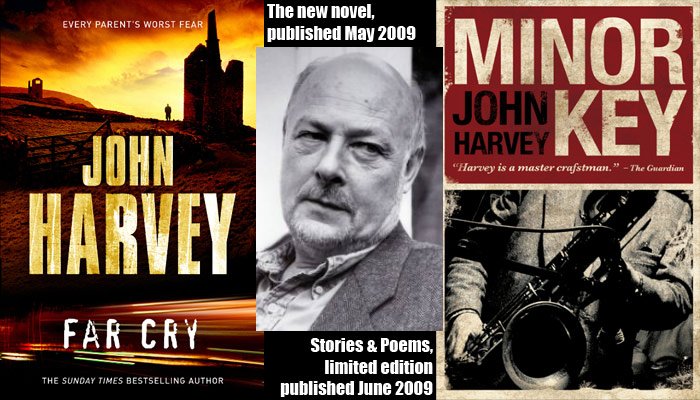

JOHN HARVEY

is one of the best known, and best-loved, British

crime writers, though he also has a strong following in the US

and on the continent. His latest book is Far

Cry and Bob Cartwright caught up

with John while he was touring the UK

to promote the new book. Predictably, the meeting

took place in Charlie Resnick’s old stamping ground, Nottingham.

Bob:

I was surprised to read in

your biography that

you were actually born in London. I suppose, like most

people, I have always associated you with Nottingham. Are there any more

surprises lurking in your early life? When, for instance, were you

bitten by

the writing bug?

It’s odd, this. I

remember always buying little

notebooks when I was a kid, but not writing much in them; and then,

when I was

at secondary school and at college I set up or edited newspaper, so if

I was

going to be any kind of a writer, it would have been a journalist, but

that

never happened. I recall starting to learn shorthand once and just not

getting

it at all, so maybe that was why it never happened. By then

I’d started

teaching – that was in the mid-60s – and, a few

articles for education

magazines, and some seriously bad poetry aside – I

didn’t write anything until

the mid-70s, when, under Laurence Jame’s tutelage, I wrote

the first of two

biker books for New English Library.

Bob:

I

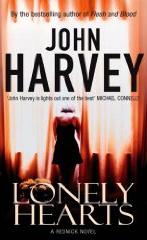

think it’s fair to say you

came to prominence in 1989 with

the publication of Lonely Hearts, the first in the Resnick series.

However,

your career as a writer started well before that with some crime

fiction, but

with a much greater output westerns and a couple of war books. Can you

tell us

a bit about those early efforts?

As I’ve suggested,

the late Laurence James, who had

been at Goldsmiths’ College with me in the early 60s, and had

gone on to be an

editor at New English Library before becoming a writer, was the main

influence

here. Laurence knew I was looking for a change from teaching and

suggested I

try my hand at writing; NEL wanted another ‘Mick

Norman’ biker book from him,

but he’d moved on to other things, so he recommended me in

his place and ‘Thom

Ryder’ was born – for two books, anyway.

After that, mostly in tandem

with either Laurence

or another editor-turned-writer, Angus Wells, I wrote some forty or so

westerns

under a batch of shared pen names, along with some fairly desperate

attempts to

turn out convincing paperbacks about mercenaries or bands of soldiers.

I had

more luck with teenage romances!

The thing about that period,

which lasted, I

suppose, for no more than five or six years, is that, because I was

writing

roughly 50,000 words a month, I got in an awful lot of practice

– and was being

paid to do so. And I think the most important thing I learned

– though I still

couldn’t pin it down in words – was how to get

readers to turn the page.

Something about pacing and rhythm and narrative expectation.

Bob:

How

did you come to

focus on crime fiction? I imagine you must have made that choice before

realizing that the Resnick series were going to be so successful.

Well, I’d tried

earlier, with four books about a

private eye called Scott Mitchell, which were pretty unsuccessful, and,

a few

other desultory efforts aside, I didn’t think about writing

crime seriously

till the late 80s, when I sat down with the writer Dulan Barber [also,

like

Laurence and Angus, now dead, Dulan wrote crime fiction as David

Fletcher and

horror as Owen Brookes] to think about the character who became Charlie

Resnick. I’d just finished working on TV series called Hard Cases, which was set in Nottingham, where I was then

living, and was about the probation service, with a multi-narrative

story line

very much modeled on Hill Street Blues.

This, and the fact that I’d been reading and enjoying a lot

of Elmore Leonard,

made me want to have another crack at crime fiction –

hopefully, using the pace

of those American models but in a recognisable English setting.

Bob:

I’m

probably being a tad

conservative but of all your crime fiction characters Charlie remains

my

favourite. I am sure you’ve been asked this hundreds of

times, but how did you

come up with a detective of Polish origin, based in London with a fondness for

modern jazz?

I think you mean Nottingham. I was very aware that

there was quite a large Polish population in the city, mostly families

who’d

come over around the time of WW2, and I liked the idea of Resnick

having that

background – then, because he would have been brought up in

Nottingham, he

would know it well yet be, in some respects, an outsider. The deli

sandwiches

sprang from that and so, less obviously, did the jazz. They were both

ways of

signaling that he was a little different from the usual home-grown

cops, and

had a quite rich appetite for music and food. Plus, I’ve

always liked to write

about jazz whenever I could – even back in the early days,

one of my

mercenaries, as a kid, had trailed Charlie Parker all round New York, surreptitiously

recording every note he played.

Bob:

Incidentally,

out of the

three characters – Resnick, Elder and Grayson –

which is your favourite? And

which one was the easiest to write for?

Well, Resnick was and is, if

only because I’ve

written about him so much; with both Frank Elder and Will Grayson,

I’ve been

able to write about the parent-child thing, which, as an older father,

has been

something of a preoccupation in the past ten years.

Bob:

Again,

an old chestnut

of a question, how do your plots materialize? Just to give it a bit of

new spin

to what extent do the different heroes generate different kinds of

plots?

It varies, but to hark back to

the previous answer,

Frank Elder came out of a short story called, I think, “Drive

North”, in which

Elder and his wife and early teenage daughter move from London to

Nottingham,

and there was something about that set of relationships which made me

want to

return to it, and so the fact that those relationships, especially the

one

between Elder and his daughter, would be central to the books, to a

large

extent determined the plots. Certainly, that was true of the first, Flesh & Blood. Then, once

I’d taken

the relationship as far as it interested me by the end of Darkness & Light, I had no real

urge to write about Elder

again.

With the new book, Far Cry, the story came first, but as

soon as I knew it involved

children, I knew I had to use Grayson, as he has two young children

himself.

I don’t think I

could have written Cold in Hand,

without the character of

Resnick – someone I felt I knew well over a period of time

– being on hand to

flesh it out.

Bob:

You

wrote ten Resnick

books, roughly one a year for ten years. That must have been pretty

exhausting

for you and for Resnick.

Yes, and it would have done

both of us good to have

taken a break before we did, but you know how it goes, publishers, on

the whole,

once they’ve embarked on a series, want the product to be

there, year In, year

out. Thankfully, partly due to the success of the books since Flesh and Blood, and due to having an

enlightened and sympathetic editor, Susan Sandon at Random House,

I’m no longer

trapped in that situation.

Bob:

The

TV series of Resnick

was probably the first to feature a contemporary crime fiction series

and was

certainly the first one that really grabbed me. I think it was probably

also

the first one to encourage publishers to see crime fiction not just in

terms of

books sales but TV rights. Was that apparent to you at the time?

Hah! What was quickly

all-too-apparent was that my

then publishers, Viking-Penguin, unfortunately failed to make much

commercial

capital out of the TV series, which, in fairness to them, was very

short lived

– only covering two books So that, for instance, they issued

a paperback of the

third in the series, Cutting Edge,

with Tom Wilkinson, who’d played Resnick, prominently on the

cover, and that

book was never filmed. The series was so short-lived on television

there was no

time for it to make a significant impact and the books suffered rather

than

gained as a result.

Bob:

Aside

from In a True Light in 2001, there seems to be a bit of

a gap from 1998

and Last Rites, Resnick’s

swansong,

until 2004 and Flesh and Blood, the

first of the two Elder books. What happened to John Harvey during those

years?

My partner and I had a child,

and the deal was that

she would go back to work as soon as she was able and I would take time

off

from writing to look after the baby. Which I loved. And it also gave me

time to

think about making a small change of direction, the Resnick books

seemed pretty

played out in terms both of ideas and sales, I was no longer under

contract,

and I had to think of something a little bit different if I was to

continue.

So, because I was aware these things were wanted, I thought more

thriller than

police procedural, and I thought longer. Elder had walked away from

both family

and job at the end of the story I mentioned before, so he became the

vehicle I

would use, and then, spending three months in New Zealand helped me to

finish

the book with, I think, a slightly different perspective.

Bob:

Elder

is very different

from and at the same time a bit like Charlie. He’s not into

jazz but he is even

more of a loner than Charlie. Once again, how did the Elder character

take

shape?

I think I’ve already

spoken to this, aside from

mentioning that because I’d got to know the area of north Cornwall between St. Ives and Land’s End fairly well, I wanted

to use it as at least a partial setting. It was only after finishing Flesh & Blood, that we went to

live

there for a year, just down the lane from where my fictional character

had his

home.

Bob:

Aside

from a couple of

walk-in parts we haven’t heard from Frank Elder since Darkness and Light in 2006. Are you

planning any more books

featuring Elder? That question occurred to me in part because you

surprised us

all a bit with Cold

in Hand

in 2008 when you brought Resnick out of retirement.

Resnick, as I’ve

suggested, seemed right for the

story and emotions of Cold in Hand. And it was relatively easy to write

about

him at length again, as I’d kept up with him with a number of

short stories and

cameo appearances during the intervening years.

Right now, I can’t

see myself writing about Frank

Elder again, but then I said that about Charlie.

Bob:

2007,

and yet another

character. The introduction of Will Grayson, a family man and very much

more of

a career copper than Charlie or Frank. Was that down to you, or was it

a more

intentional recognition of the changing face of police detective work

with its

emphasis on proper procedures and budgets?

Once again, there’s

a short story at the heart of

it. I wrote a story called “Snow, Snow, Snow” for a

collection out together by

Bob Randisi in the States and he liked the by-play between Will Grayson

and

Helen Walker so much, he said I had to write about them in a novel.

That was

that.

Bob:

You

are currently

promoting the new Will Grayson, Far Cry.

For those who haven’t read it yet can you give us a bit of a

taster?

The idea for the

book came from a conversation with the novelist

Jill Dawson had written a novel, Watch Me

Disappear [Sceptre, 2006], which had its genesis in the Soham

murders,

which had happened close to where she lives. When we met, and talked

about that

novel, the disappearance of Madeleine McCann was very much in the news,

and

what Jill and I talked about, in the main, was the effect that losing a

child

in such circumstances might have on that child's parents, and I went

away from

our meeting with the germ of an idea for a new book, one which would be

based

upon the very different responses and actions of parents whose child

has died

suddenly or disappeared.

Bob:

John

Harvey, the crime

fiction writer, is probably among the most recognised UK author in terms of

awards. How important are awards to crime fiction writers and how does

that

recognition compare with huge book sales?

One pays the mortgage, the

other doesn’t.

Bob: I have

to confess that I am not a great fan of short stories and that

ignorance has

been evident now in some of the questions I’ve asked you. But

the sheer volume

of short stories you have written suggests that you do really enjoy

writing

them. They also seem to provide a vehicle for you to test out

characters and

themes. Are there any other benefits of short stories for you?

You're right, they can be a

useful way of testing

out characters you think might be interesting to write about at greater

length.

"Walking them round the block", as someone - Elmore Leonard? - once

said. It's certainly something that he does from time to time. For me,

it has

also been a way of filling in the gaps between the novels, the Resnick

novels

for instance, taking the time to keep up to date with some of the minor

characters - and Resnick himself.

Other benefits? By very

definition, they're short.

You can write a story in one or two weeks and then it's done. None of

this

10/12 months lark!

Having said all of that, I've

mostly written them

because I've been asked to contribute to a particular collection or

magazine by

an editor who knows my work. This very morning, for instance, I had an

email

from Robert Randisi in the States, an editor for whom I've written a

number of

stories in the past, asking me if I'd like to contribute something

towards a

collection based around the history of the strip tease. Why not?

Bob:

Final

question. You seem

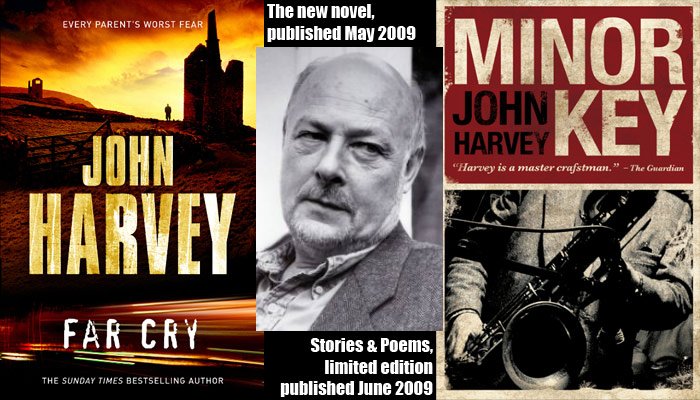

to have fingers in all sorts of pies – crime fiction, poetry,

poetry and jazz,

children’s writing, publishing, parent and Notts County supporter. Which gives

you most pleasure at the end of the day? And what lessons do you have

for us

mere mortals who can’t seem to manage our time quite as

effectively?

I’ve always found it

difficult to simply sit around

and do nothing – and I’m fortunate to have found

pleasure in a variety of

things. Spending a lot of my adult life living in my own has helped to

make me

the kind of person who plans his time so as not to waste too much of

it. In

some areas, I’m organised, I suppose, to a point some people

find slightly ridiculous.

There are concert tickets, for instance, for April 2010 already

purchased and

in drawer waiting, and I’ve renewed my Notts County season ticket for next

season. Lessons? Plan. Make lists. Carry them out.

Most pleasure? Watching my

daughter working with

her sprint coach at the track. Being at the Royal Festival Hall last

Saturday,

along with both my partner and daughter, watching Viktoria Mullova play

the

Brahms Violin Concerto. Getting a letter out of the blue from someone a

few

days, saying how much they’d been touched by my books.

Walking, early this

morning, on Hampstead Heath. Writing a really good sentence.

Read

Bob’s

review of FAR CRY

To

find out more on John Harvey visit his website

|