|

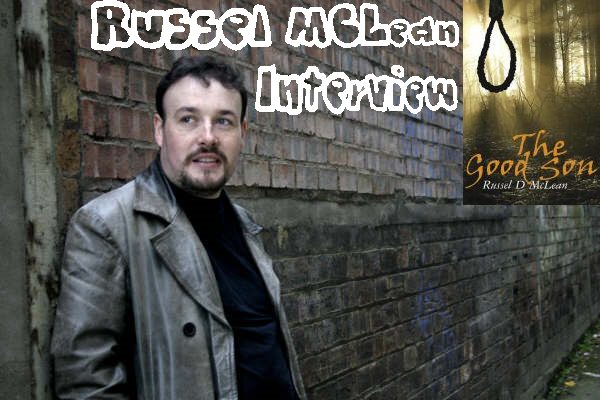

Fans of cutting-edge noir

with a Scottish flavour will already be familiar with the name Russel D. McLean.

The creator of the webzine Crimescene Scotland and the author of some

particularly spiky short fiction, which can be found online and in print, has

now taken the leap into the novel form. His first offering, The Good Son,

is out now. Shots sent TONY BLACK to talk to McLean.

You're known, among other

things, for the website Crimescene Scotland ... how did that come about?

Pure accident. In my hallowed youth, I made the mistake of thinking I might be

able to run my own business, specifically a crime-specialist bookstore. I quit

when I came to my sense and realised if I did, I'd run into debt fast. But I was

left with some things including the webspace. So, for fun, I started rounding up

some people to help and suddenly it took on a life of its own.

Keeping a website going is

tough, but you lasted five years, a good run...

An excellent run, but then we never really had a plan. I think it helped that me

and the main contributors were initially in p/t employment. The reason the zine

came to an end is, as ever, real life got in the way for everyone and we just

couldn't keep up. Wish we'd had a more dignified end to the main segment of the

zine rather than it simply petering out after repeated attempts to do one more

issue. Luckily, though, the brand lives on with the CSS blogzine focused on

reviews with the occasional interview.

Let's stick with the zines

for a bit, I promise I'm going somewhere with this, your short fiction has been

published widely online ... does online fiction get the credit it deserves?

Not always. But of course there's a lot of dross out there. The problem is that

so many people are doing it for the love and inevitably that means that for

every Pulp Pusher or Shots or Plots With Guns, you've got five or six really

poorly run zines which have no markup for quality, no real gatekeepers, no real

editing techniques. However, I think that when you get to the quality zines (and

they always rise to the top) you're finding some of the best and most varied

fiction out there. Thrilling Detective, Spine Tingler, PWG... all these guys,

they've truly got it going on. And you'll notice that a lot of the rising

novelists are coming out of these markets, too.

You're a prize-winning short

story writer, it's obviously a form you like.

It's a form I love...but prize winning? I was nominated for some things a few

times (or at the very least put forward by some generous editors), but did I

ever win? I love doing it, though. I think it's more difficult than people

believe though. I'm actually a fairly slow writer in some regards. I have to get

it right, have to get that voice, or it all goes. I'm no Stephen D Rogers, a

short story writer whose output is absolutely phenomenal. Nor am I Edward D Hoch

who I believe had a short in every issue of AHMM for decades until his recent

death.

I thought you'd picked up a

prize ... sure it's in the post. Okay, so let's talk about The Good Son,

your debut novel ... tougher to write than a short?

Yes and no. It was a very different kind of challenge. I discovered along the

way that I'm not a doorstop novelist. I think the shorts taught me brevity more

than anything. I still like King's analogy for the short story being a kiss in

the dark with a stranger to a novel being a full blown affair; both have their

appeal but are very separate experiences.

You don't like

the doorstop novels?

I think doorstop novels can be beautifully done when they justify their length

(see Ellroy's American Tabloid, Winslow's Power of the Dog, 95% of

Stephen King's IT) but as a reader, a book has to work hard to keep me

interested past about 300 pages. Elmore Leonard gave the advice everyone should

remember: leave out the parts the readers skip (or at least, he said words to

that effect).

For those who haven't read

The Good Son, give us a quick run through...

When a Scottish farmer finds his estranged brother's corpse hanging from a tree

in Tentsmuir forest, he hires Dundonian PI J McNee to look into the dead man's

life. McNee - still recovering from the accident that killed his fiancé -

uncovers very disturbing truths about the dead man and before long is caught in

the middle of a gang war that brings two London hard men to the streets of

Dundee.

Clearly, it's a barrel of laughs.

Why Dundee?

Because we're fed up being kicked around by Glasgow and Edinburgh. Actually,

that's close to the truth. People have an image of Scotland, and I just wanted a

slightly new angle on it. And Dundee's a fascinating city - Scotland's fourth,

you know. There's a great deal of history here and what I love most is that it's

still being written. Dundee's moved from an industrial town to an impoverished

town to a town of innovation and research ... and the changes are still

happening. It's a brilliant city to set a crime novel considering the kind of

tensions that come with these sorts of change.

At your launch party you

sold 129 books, clearly Dundee's been waiting for its own PI...

Maybe. Titles with a local connection always do well in Dundee. I don't know how

to explain it, but I'm honoured and delighted at the reception the book had. And

I should point out that I'm hearing underground rumblings that McNee may not be

Dundee's first PI (actually he's not anyway, since the character in some of the

early short stories is also a Dundonian PI) but those are currently unconfirmed

and I'll get back to you on that

Is the PI novel making a

resurgence, do you think, against the dominant police procedural?

I don't know. I think there's always a market for the PI story, and maybe the

time is coming round again. In the UK the grand procedural novel is still king,

but there are UK writers kicking against that: Banks, Bruen, Waites and myself

are all writing PI novels of one sort of another. In the US, of course, the PI

is really coming back with guys like Sean Chercover (why doesn't he have a UK

deal?) and Dave White (ditto) coming along to give it a beautiful kick in the

arse.

Your day job is a

bookseller, you don't go i nto that line without a passion for the printed word,

I assume.

Absolutely not. I am - and remain - a voracious reader, and I love recommending

books to people, helping them find the authors that they can connect with.

Naturally my bias is towards crime fiction - and it's one of the reasons I'm

glad they let me play with the crime section in the day job - but I'm in love

with anything that's well written.

It's strange, but when I did a few years of English at university, I read far

less and was far less critical of fiction than I am now. I also didn't read half

as broadly during those years, either. I'm at a loss to explain why.

A few years of

English ... did you change course? If so, why?

I went pure philosophy in the end for my Honours. The reason being there was

more on the courses that excited me, and I felt like I could enjoy reading

fiction again if it became a leisure thing.

How gutted am I to realise you can do whole courses on the history of crime

fiction?

But I loved doing the philosophy courses, so there we go.

So, what drew you to such a

weighty course of study?

I think the ideas drew me. Making sense of the world around you is at the heart

of philosophy, and something in that appealed to me greatly.

How would you describe your own philosophy? What philosophers do you

rate/identify with?

That's a toughie, especially having been away from the scene for so long. By the

time I left, I was working in the field of Philosophy of Mind, getting mixed up

in philosophy of science as well. My final dissertation was on emergentism: a

discipline which started in the early twentieth century and which was used to

try and explain the relationship between mind and body. Variants of the original

emergentist doctrine were coming back into play as ways to look at this

phenomenon, and I tried to explore these in my final years.

Ultimately, though, I'm not sure whether I was cut out to really do it, and in

some ways perhaps my failure to secure funding for a PhD was really a blessing

in disguise.

The big names who interested me most throughout my studies were probably

Wittgenstein (although I don't know that I ever fully "got" what he was doing

past the Tractatus), Russell (Philosophy of Logical Atomism was one of the most

concise and straightforward works I read) and more recently Daniel C Dennett

(who is a mover and shaker in philosophy of mind/science).

I should also point out that Wittgenstein was (according to what I could dig up)

a fan of noir and hardboiled fiction - - witness this letter concerning Sweet

and Smith's Detective Story Magazine from 1929: Your mags are wonderful. How

people can read Mind if they could read Street & Smith beats me. If

philosophy has anything to do with wisdom there’s certainly not a grain of that

in Mind, and quite often a grain in the detective stories.

Amen, Mr Wittgenstein, Amen.

Kant is the only philosopher I am aware of who made an appearance in crime

fiction (In one of Michael Greggorio's novels) which I find greatly frustrating

considering how much I hated Kant's works. Not because of what he said, but

because he was one of those philosophers whose writing often felt deliberately

obtuse. He could write sentences that lasted near a page in length. As an

undergraduate, I often felt Kant to be my nemesis.

Has your philosophical studies influenced/assisted your writing in any way?

Probably. Strangely, reviewing philosophy texts for my postgrad course affected

the way I reviewed fiction (taking each work on its own merits, figuring out if

it achieves its own goals). But I don't know if there are any direct links

between my studies and my fiction. Although I didn't specialise in it, I had a

great time studying ethics as part of my taught postgrad. Probably my cynical

approach as to why we should ever do the "right" thing (if there is such a

thing) colours my crime fiction.

Kierkegaard famously said, 'Trouble is the common denominator of living.' I

think crime writers know this instinctively, discuss...

It's a very noir thing to say, isn't it? And I think that he's right. Certainly.

trouble is the common denominator of all fiction, because trouble is conflict

and conflict is the very essence of fiction; used to illuminate characters and

ideas and play them off against each other.

Tell us about The Good Son's

road to print.

Long. Painful. Finally triumphant. I don't know what else to say. I wrote a

book, went through a couple of agents, wrote some failed manuscripts and then

rewrote one of the most promising for Agent Al [Allan Guthrie of Jenny Brown

Assoc.] which eventually became The Good Son and he managed to sell it.

Took a long time for me to learn my craft. Writing the shorts for so many years

helped, of course.

What did any of this teach

you as a writer?

It taught me persistence. It taught me the value of a good agent, one with whom

you have a rapport. And it taught me that you've got to sweat like a bastard to

get where you want to go.

You've spoken about the

influence that film has had on your writing ... what movies do it for you?

I love film - I love any form of narrative fiction, providing it's well done.

But the films that I love...

Serpico (I tried to grow a beard like that ... failed), The Godfather

(simply mesmerizing), near anything by the Coens (this aggression, man, will

not stand), The French Connection (Hackman at his finest), Bullitt

(saw it for the first time in a cinema for a film course - the chase blew me

away), The Limey (I love the way it chops up linear time - and it's the

closest we'll get to a proper Parker film post Point Blank, I fear),

Alien/Aliens (need I explain?), Blade Runner (inverts the original

novel, but does so quite beautifully), Midnight Run ("Smoking or non

smoking?" "Take a wild fuckin' guess.") and ... God, thousands more.

My top cult tip for today, of course, is the bizarre Trigger Happy (or

Mad Dog Time in the US) which is the single weirdest gangster pastiche

starring Jeff Goldblum and Richard Dreyfuss you'll ever see. It's not even got a

UK DVD release ... you can only find old VHS tapes, that's how cult it is. But

... absolutely bizarre and absolutely brilliant.

And for Agent Al, I must mention Calvaire (The Ordeal) ... a strange

Belgian film which features horrific scenes of torture and ... the penguin

dance.

And the writers?

As with the films ... so many. A pot shot selection - James Ellroy (American

Tabloid - killer, absolute killer), Philip K Dick (not the world's greatest

prose stylist, but man, what ideas were at work in there - and I'll throw in a

shout out to Alfred Bester for mind bending ideas as well), Chandler (the

opposite of Dick in a sense - a killer stylist, although not always the most

incredible of plots), Richard Stark (I never met a Parker I couldn't read),

Elmore Leonard (one word: dialogue), Domonique Manotti (I love the Daquin

novels) and Manchette (Only just finished Three To Kill and blown away by

the way he deals with violence as well as the extremely compact nature of the

novel itself; nothing is wasted)

And catching up to the newer kids on the block - Don Winslow (Four words: Power.

Of. The. Dog.), Ken Bruen (Brady's Bad Fucked - those words, right there, I was

hooked), Allan Guthrie (I was a fan long before he was my agent), Ray Banks

(Although I don't like the idea of the series ending, roll on the last Cal Innes

novel - I'm stoked), Charlie Williams (been a while since we've seen anything

from him, but the Mangel trilogy is incredible), Charlie Stella (best dialoguer

since Leonard), Sean Chercover (If this man doesn't take over the world, I'll be

very surprised), Tom Piccirilli (his horror stuff is amazing, and his more

recent crime novels are just ... The Fever Kill blew me away) and of

course there are his fellow Canadians Sandra Ruttan and John McFetridge who have

made me realise that, ya know, there's a crime fiction scene in Canada and it

can be every bit as cool and engrossing as its American counterpart.

As with the films, of course, there are a million other writers out there whose

work I adore as well. But I'll go on forever if I don't stop myself.

Of course, there is this young Scots whippersnapper called Tony Black I keep

hearing about ... Apparently some reviewers absolutely dug his noiresque take on

modern Scotland...

You're way too kind ... How

important is capturing the modern Scotland your work?

I think capturing any

location is very important to me. If only because I'm currently writing books

set in Scotland, I'm determined to present the country as I see it. Doesn't mean

I'll write about it forever, but I feel that inasmuch as it shapes my characters

and their actions, it is indeed very important to me. I'm not exactly a

nationalist, but I think that Scotland very much has a character and history

that it would be criminal to ignore when writing about it. I also feel very

strongly that this "romantic" image of semi naked Highland Lairds in kilts is

one that needs to be swiftly laid to rest. You can include Scottish character

and heritage in your fiction without getting all twee and tartan on the readers.

The Good Son

is published by

Five Leaves Press

pbk £7.99

Tony Black's first novel

PAYING FOR IT was published by Random House in 2008. His follow-up GUTTED is out

in May 2009. More of his writing can be found at: Scotsman.com, Books from

Scotland, Thug Lit, Pulp Pusher and at Out of the Gutter. Black lives and works

in Edinburgh. Reach him via his website: www.tonyblack.net

|