|

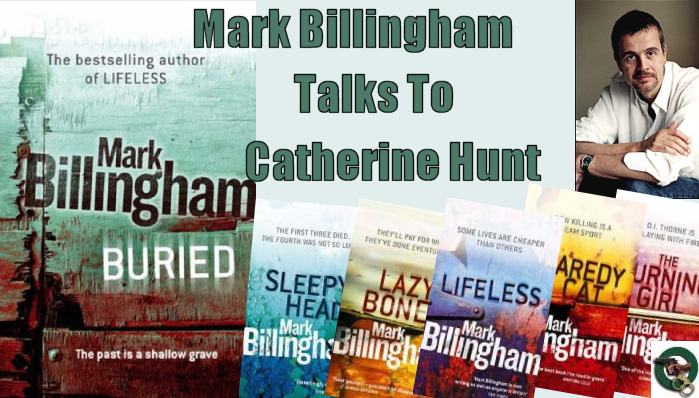

I was lucky enough to read an advance copy of Mark Billingham’s latest book, Buried,

I’m torn between the glow that follows a treat and the upsetting knowledge

that I shall have to wait a good while before reading another in the series

featuring DI Thorne. Of course, I could always start again with Lazy Bones and

re-read all six but, to do that, I’d first have to get some back from my

son who has become as much of a Thorne addict as myself.

I was lucky enough to read an advance copy of Mark Billingham’s latest book, Buried,

I’m torn between the glow that follows a treat and the upsetting knowledge

that I shall have to wait a good while before reading another in the series

featuring DI Thorne. Of course, I could always start again with Lazy Bones and

re-read all six but, to do that, I’d first have to get some back from my

son who has become as much of a Thorne addict as myself.

Mark

Billingham, could I start by asking you the question my son wants me to put to

you? Are you willing to give up Country and Western and try some of the good

music he’s happy to put your way? He says he’d like to repay some of the

pleasure you give him. After all, fair’s fair.

It’s a generous

offer, but I couldn’t give up C&W. Say goodbye to Cash? And Waylon Jennings,

Steve Earle and Lucinda Williams? To Dolly Parton?? Are you serious???? When

it’s good – and obviously I’m not talking about big hats and lost dogs here -

country music does for me what the best crime fiction can do. It can tackle big

issues, dark subjects, but it presents them in a way that’s entertaining and

keeps you coming back for more. A song like “Ode To Billy Joe” which admittedly

is at the poppier end of the scale is a REALLY bleak story, but one which is

simply a joy to listen to. I love the voices of the best country artists; the

ones that can squeeze as much emotion from a song as Emmylou Harris does on

“Boulder To Birmingham” or Cash does on his amazing version of “Hurt”. White

man’s blues...whatever you choose to call it, it gets to me in a way not much

music can. Not just the dark stuff either. “He Stopped Loving Her Today” by

George Jones still brings a tear to my eye...

I’m

interested in the dark side of your books. You don’t have scenes of prolonged

torture but some episodes are definitely not for the squeamish. The Burning

Girl was about organised crime and what you called , ‘ the line that criminals

cross for money.’ Why did you let Thorne and his friend, Chamberlain cross

that line when they forced Brookhouse to speak by threatening him with an iron?

Did you plan that or did it surprise you as much as it seemed to surprise Thorne

and Chamberlain.

Dealing with

the subjects I do, it’s inevitable that some scenes will be hard to deal with.

You cannot write about violence, about the effects of violence, without

to some degree laying them out. Obviously you need to walk that line between an

honest depiction of these things and something that becomes pornographic or

gratuitous. The scene you mention did creep up on me to a degree. I don’t plan

books out, so it wasn’t something I knew was going to happen. I liked the idea

that it was the older woman that cracked; that found a darkness inside herself

that led to this violence. She had no choice in the end but to do what she did,

and to cross the line, however distasteful it was. The consequences of this, and

of the fact that Thorne stood by and let it happen, follow both those characters

into successive novels.

Thorne is a character who, with each book, becomes more complex. You make sure

that past events affect him and you take care to pick up where the last story

left him. His father’s death , at the end of The Burning Girl, disables him so

much that he is given ‘gardening leave’ but, in Lifeless, he manages to climb

out of that pit and solve the mystery of who is murdering homeless people. In

Buried he is still suffering from a mixture and guilt and grief. How do you

make his misery so very convincing?

Thorne is a character who, with each book, becomes more complex. You make sure

that past events affect him and you take care to pick up where the last story

left him. His father’s death , at the end of The Burning Girl, disables him so

much that he is given ‘gardening leave’ but, in Lifeless, he manages to climb

out of that pit and solve the mystery of who is murdering homeless people. In

Buried he is still suffering from a mixture and guilt and grief. How do you

make his misery so very convincing?

This is exactly what I was talking about before. If your characters remain unaffected by what has happened to them, then you are basically writing cartoons. Thorne would just become like Tom the cat, his head battered into the shape of an anvil in one shot and then perfectly normal again in the next. Surely we all carry our pasts around, don’t we? Having said all that, there’s another line to walk here. Each book in the series has to stand on its own, and it can’t be too full of references to previous ones. It’s important to acknowledge the past, the scars that have been left inside and out, but without dwelling on it to the detriment of the new story you are trying to tell. I take it as a huge compliment that Thorne’s misery is convincing, because truly I am a very happy person. It’s certainly not something I’m dredging up from within myself.

You

convey Thorne’s love of his father quite beautifully. The phone calls and the

visits and, in the latest book, the memories, are all very moving. One of my

favourite scenes occurs in The Burning Girl, when Thorne takes his father and

his father’s friend to spend a weekend in Brighton with Auntie Eileen, and his

father has to be escorted out of the bingo hall for shouting hilarious

obscenities. It makes me hoot each time I read it but it’s terribly sad. Have

you any experience of friends or relatives suffering from dementia?

No, thankfully

it’s not something I’ve ever been close to, but it was a subject that I took

very seriously when it came to the writing. As far as research goes, you learn

which things you can take liberties with and which you have a duty to portray

accurately. The portrayal of Jessica in “The Burning Girl” and the aftermath of

facial scarring was one, and Jim Thorne’s Alzheimer’s was another. While I tried

to get it right, I was also keen that it wasn’t unremittingly bleak, so I’m glad

you mentioned the bingo sequence, which is also one of my favourites. Humour is

important to me in this respect. I wanted Thorne’s father to be a funny guy, in

the same way that I wanted Alison in “Sleepyhead” to be funny. A little light

can really blacken the darkness, if you know what I mean.

I’m

going to be effusive now. Thorne would certainly be in my list of favourite

detectives. He’s funny, modest, a good friend, kind - well quite kind - to his

cat, Elvis, only sulks occasionally and is brave or foolhardy enough to tell

pompous people like Jesmond what he thinks of them. He doesn’t have instinctive

feelings about who the murderer is but knows that solving cases takes a long

time and patient police work. What is is about Thorne that appeals to you or,

like Agatha Christie, do you ever regret inventing your main man?

I’m

going to be effusive now. Thorne would certainly be in my list of favourite

detectives. He’s funny, modest, a good friend, kind - well quite kind - to his

cat, Elvis, only sulks occasionally and is brave or foolhardy enough to tell

pompous people like Jesmond what he thinks of them. He doesn’t have instinctive

feelings about who the murderer is but knows that solving cases takes a long

time and patient police work. What is is about Thorne that appeals to you or,

like Agatha Christie, do you ever regret inventing your main man?

I certainly

don’t regret inventing Thorne and will happily go on writing about him until he

fails to interest me. What is important is that I don’t really know any more

about him, book by book, than the reader does. There is no complex biography

tucked away in a drawer, and I’m learning about him at the same rate as anyone

else. It’s simply working on the principle that if I can stay interested in him

then hopefully the reader will feel the same way. All I really know is that I

want him to be unpredictable and that he will not always be likeable. I don’t

think a hero has to always do the right thing to be a hero. In many ways, Thorne

is a terrible detective and he’s no better at navigating his way through his own

private life. If I had to describe him quickly, I would say he is a man who

doesn’t know when he’s not wanted. But, rather more sadly, he does not know when

he is, either.

Did

you deliberately try to choose characters who would break the conventional

mould? I’m thinking of Thorne’s friend and occasional flat mate, Hendricks, with

his piercings and his gay relationships. The jokes that he and Thorne share and

their conversations are some of the most successful parts of your books. It’s

fairly rare to see male friendship so well portrayed. Would you tell us how you

created Hendricks?

I don’t think

I’d decided that Hendricks was going to be gay when I began to write the first

book, and I certainly wasn’t trying to create a “wacky” or “interesting”

character. I’ve become increasingly fond of the relationship between Thorne and

Hendricks – especially when they were living together like a twisted version of

Morecambe and Wise - and it’s interesting for me that it isn’t always an easy

one. It would have been simple to make Thorne desperately sensitive and liberal

when it came to his friend’s sexuality, but I find it more honest, and

interesting to write about the fact that Thorne is often awkward, unsure and

uncomfortable with it. This comes to something of a head in the book I’m just

finishing.

You

have an impressive mastery of police procedure and trot out police acronyms

with amazing confidence. In Buried you describe how the Kidnap Investigation

Unit works and you do it so well that it is completely convincing. How come?

Over the course

of the books, I’ve come to know several police officers very well and now have a

number of good sources (both official and not so official) that I can call upon

when I have to. I try to keep on top of the procedure because things change very

quickly, not least of all the prosaic stuff like what things are called. In the

course of six books, the department Thorne works for has changed its name four

or five times. “Buried” was actually the hardest book to write in many ways,

because the Met is very protective when it comes to how kidnaps are

investigated. I know far more about murder than I do about kidnap. It makes

sense of course. With a kidnap investigation there is still a human life at

stake, so the police are naturally reluctant to reveal how these investigations

are carried out. One of the few things I do know is that it is a far more

common crime than anyone realise. One of the reasons this is not widely known is

that a press blackout is almost always enforced. So with “Buried” I was far more

reliant on those unofficial sources I mentioned…

Over the course

of the books, I’ve come to know several police officers very well and now have a

number of good sources (both official and not so official) that I can call upon

when I have to. I try to keep on top of the procedure because things change very

quickly, not least of all the prosaic stuff like what things are called. In the

course of six books, the department Thorne works for has changed its name four

or five times. “Buried” was actually the hardest book to write in many ways,

because the Met is very protective when it comes to how kidnaps are

investigated. I know far more about murder than I do about kidnap. It makes

sense of course. With a kidnap investigation there is still a human life at

stake, so the police are naturally reluctant to reveal how these investigations

are carried out. One of the few things I do know is that it is a far more

common crime than anyone realise. One of the reasons this is not widely known is

that a press blackout is almost always enforced. So with “Buried” I was far more

reliant on those unofficial sources I mentioned…

You

have involved Thorne with serial killers, with the squad dealing with London

gangs and now with kidnapping. Where are you thinking of planting him next?

He’s going to

retire and grow vegetables, and work part-time as a Johnny Cash look-alike while

solving mysteries with the help of Elvis in a quiet Cotswold’s village. Or not.

I’ve just finished the seventh Thorne novel, and all I do know is that I’m going

to give him a rest for a book or two. I don’t really know what Thorne is going

to be doing each time until I sit down and start the book. Suffice it to say

he’s never going to be after people for non-payment of library

fines.

Just

as one can’t imagine Rankin’s Rebus anywhere but in Edinburgh, so Thorne fits

London and London fits Thorne. He’s often telling his colleagues snippets of

London history and you give very exact details of his surroundings: waste land,

streets and individual buildings. Does that involve a lot of research or is it a

pleasure?

It’s both

really. I like to go out and “recce” locations, much as a film director would.

When I’m doing this, I discover stuff that I think makes the books richer and

certainly makes the descriptions – the sounds, the smells – more evocative than

they would be if I just sat at my desk making shit up. I’m fascinated by the

dark history of the city and Thorne shares much of that fascination. Once I

start looking into the history of a building, or an area, or even a street,

stuff comes out which I have to use. It wasn’t until I started wandering around

the cemetery where Ryan’s funeral takes place in “The Burning Girl” that I

discovered it was also where most of the city’s most notorious highwaymen were

buried. I didn’t know that the Magdala Tavern was where Ruth Ellis shot her

boyfriend, or that you could still put your fingers in the bullet holes, until I

went there to take a look. I couldn’t really write about anywhere else other

than London. Certainly not anywhere rural. Animals and scenery…ecch!

In

Lifeless, Thorne goes underground and mixes with homeless people. He even sleeps

rough, eats what they eat and deprives himself of the company of his friends.

It is very vivid but, more than that, the book seems to be speaking for the

homeless in a way that non fiction would not be able to. Was that part of your

plan when you wrote it?

In

Lifeless, Thorne goes underground and mixes with homeless people. He even sleeps

rough, eats what they eat and deprives himself of the company of his friends.

It is very vivid but, more than that, the book seems to be speaking for the

homeless in a way that non fiction would not be able to. Was that part of your

plan when you wrote it?

My first duty

is always to tell a good story. If, during the course of that, you can say a few

other things, then so much the better, but anyone who sets out to write about

this or that issue is probably going to come unstuck. I think it would be the

kiss of death if I sat down to try and write my “homeless’ book or my “asylum

seeker” book or whatever. Crime fiction can certainly tell us a lot about the

world we live in; can cast a light into some of the darker corners of society.

But I think it does that through the story. If it works, it can, as you suggest,

be more powerful than some non-fiction, but the story, and the characters moving

through that world, need to be rock solid before anything else can happen.

In

Buried Thorne speaks of TV detectives . He says, ‘TV shows are fond of showing

coppers , and those they needed to speak to , strolling slowly through the crowd

at noisy dog tracks, arguing in meat markets, or blowing cigarette smoke at each

other across empty warehouses in the early hours... But the truth was over-lit

and dirty-white. It sounded like the hum of distant traffic and felt sticky

against the soles of your shoes. It smelled of old blood or fresh bullshit, and

no amount of gasometer-filled skylines was going to make it gritty. The

atmosphere - in sweltering front rooms and shitty little offices - could make

your guts jump for sure, and the hairs on the back of our neck stand to

attention, but truthfully, it was rarely one of menace. Or of danger.

Watching

people sob, and rant, and lie.Watching them tremble and gulp down grief.It was

more like embarrassment.’

Watching

people sob, and rant, and lie.Watching them tremble and gulp down grief.It was

more like embarrassment.’

This is

such great writing. Nevertheless, I hope we might see Thorne on TV some time.

Any chance?

Thanks very

much. It would be nice to see Thorne on TV, but only if it’s done well. The

books have been optioned and scripts are being written, but this of course is no

guarantee the show will ever see the light of day, so I’m not holding my breath

in fevered anticipation. It’s a mixed blessing if it does happen. We all have

our own ideas about characters and they rarely bear any resemblance to their TV

incarnations. It’s not something you can take too seriously. I like to cast

books in my head using only actors from “Carry On” movies. So obviously Sid

James as Thorne, Kenneth Williams as Hendricks, Hattie Jacques as Carol

Chamberlain etc etc.

Have you lots of ideas for further crime novels or do you let real crime influence you? What next and will it be soon? Please .

I wish I had lots and lots of ideas, but I don’t usually have any more than the ghost of an idea, that will hopefully gain a little flesh as I sit down to write the next book. The Thorne novel I am finishing now will be called DEATH MESSAGE, and I imagine it will be published in the early summer of 2007. I don’t want to say too much about it, other than a hint for those readers who care about such things that Tom might be getting close, well sort of, to a happy-ish relationship. In a few months I will start work on a standalone. All I really know about that is that the central character will be a heavily pregnant woman. A certain C&W loving detective may make the briefest of cameo appearances, if I can find something for him to do, and anyone can be bothered to look hard enough.

Buried by Mark

Billingham is published by Little, Brown May 2006

Hbk £12.99 ISBN: 0316730505

| Webmaster: Tony 'Grog' Roberts [Contact] |