|

Poisoned Pens

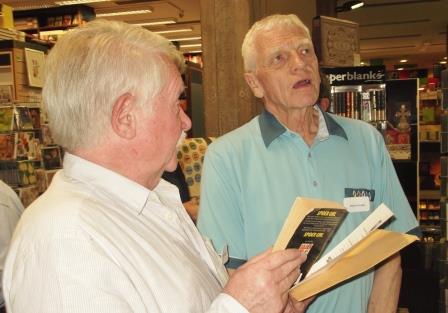

The annual What’s Your Poison? Summer party at

Cambridge’s famous bookshop Heffers was, as usual, a humming and vibrant affair

mixing authors (who are not allowed to make speeches) with readers, who often

turn out to be better-read than the authors.

It was a

personal pleasure to share a table groaning with books (mostly his) with Peter

Lovesey who, gentleman that he is, tried to look interested while I bored him

with a particular piece of prose I had just read.

As always at

these highly sociable events, it was fun to mingle and dispute with colleagues

such as the double-award-winning Len Tyler and fellow East Anglians Barbara

Cleverly and Jim Kelly, and to have dinner afterwards with two more: Jeremy

Cameron and Janet Neel.

Yet even

though I am something of an old stager at such events, I still get quite a kick

from meeting new people; not just new readers – always a pleasure and often a

surprise as I thought I knew them all – but writers.

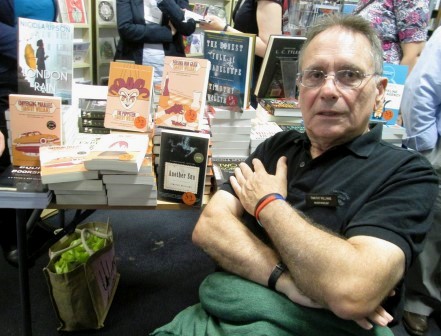

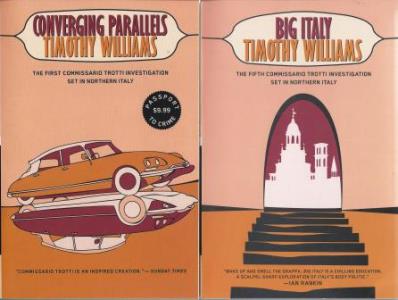

For example,

I had never before met Timothy Williams, although I did admire his ‘Comissario

Trotti’ novels set in Pavia in Northern Italy, when they began to appear in the

1980s.

Tim deserted

Italy for Guadeloupe some time ago and his recent fiction has been published

first in French, but I am delighted to see that the Trotti series is now back

in print, very attractively republished under the Soho Crime imprint in

America. Newcomers to the series should probably begin with Converging

Parallels from 1982, although Tim insisted I try his later Big

Italy, from 1996, and even bought me a copy to make sure I did!

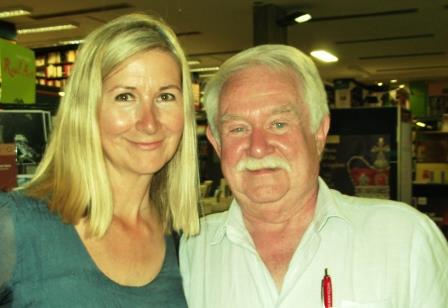

Even more

satisfying, though, is when one meets a crime-writing star of the future, as I

am sure Charlot King will be, for she told me as much – and no author has been

known to lie or exaggerate whilst in the hallowed halls of Heffers.

Appropriately,

as this was the What’s Your Poison? Party

in Cambridge, Charlot’s first novel is entitled Poison and is set in

Cambridge. Already available as an eBook (and therefore, on religious grounds,

I have not seen it), I am assured that it will appear as a proper book in

September.

Radio and TV Times

I do not

listen to Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour as regularly as I perhaps should, though I have long been a fan of presenter Jenni

Murray since the days, more than a decade ago now, when we were both judges for

the Crime Writers’ Dagger awards. In July, the programme provided an extra

treat in its regular 15-minute drama slot with a production of Val McDermid’s

comedy crime play Dead Clever - a

deliciously tart murder mystery set in a Northern university where the

disreputable professor of Geography is bludgeoned to death with his own antique

globe, sparking a “who offed the prof?” police investigation.

July also saw

two very effective thrillers grace the small screen, both starring Anna Friel.

Based on real events in WWII, The

Saboteurs is a Norwegian

production retelling the story of the Allied attempts to disrupt the manufacture

of heavy water in occupied Norway and thus halt the development of a Nazi

atomic bomb. This splendid series was

dramatically gripping with the highest production values and unusual in that

the dialogue was in multiple languages: English, Norwegian, German and Danish.

In Odyssey, Friel takes the central role of

an American special forces soldier betrayed by her own side as part of a global

conspiracy, to Islamist terrorists in Africa. You’d have thought that after

taking on the Nazis’ atom bomb programme, that dealing with the Pentagon and

the military-industrialist complex in America would be less harrowing; but

you’d be wrong.

Awards News

There are so

many awards for crime-writing nowadays that hardly a day can go by without a

writer somewhere beating themselves up for not getting one or risking an

aneurism by taking the results too seriously.

Since last

month’s column, I have to report - well I don’t have to, but it’s become

something of an obsession now - that the Strand Magazine Critics Awards (does that mean critics of the Strand Magazine?)

have been made in New York for Best Novel and Best First Novel, and in Japan

the Maltese Falcon Society has, unsurprisingly, made its annual Maltese Falcon

Award award.

I should also mention that the International

Association of Media Tie-In Writers (no, me neither) announced the winners of

the 2015 Scribe Awards at Comic-Con in San Diego.

Yet there is one award which I do take seriously,

and it is one for which I am completely ineligible. The Ngaio Marsh Award for

the best crime-writing from New Zealand is now in its sixth year and the

shortlist is an impressive one, comprising: Five Minutes Alone by Paul Cleave, The Petticoat Men by Barbara Ewing, Swimming in the Dark by Paddy Richardson, The Children’s Pond by Tina Shaw and

Fallout by Paul Thomas.

In the early years of the award, named after one of the

great ‘Golden Age’ queens of crime writing, I had the honour to be one of the

international judges and discovered the quality of the work of, among others,

Paul Cleave, Vanda Symon and Paddy Richardson, for which I am grateful to the

organiser, the inexhaustible Craig Sisterson. This year, I am personally delighted to see

Paul Thomas on the short list for the award, which will be presented in

Christchurch in September.

The Name’s Bonda…

I’m sorry,

but I couldn’t resist.

Acclaimed as

the ‘Queen of Polish crime writing’ (and who am I to naysay that?), Katarzyna

Bonda is to have four of her novels published in English for the first time, by

Hodder.

Expectant

fans will have to wait until early 2017, though, for the first, Girl

at Midnight, at which point we can all say: ‘We’ve been expecting you,

Miss Bonda…’

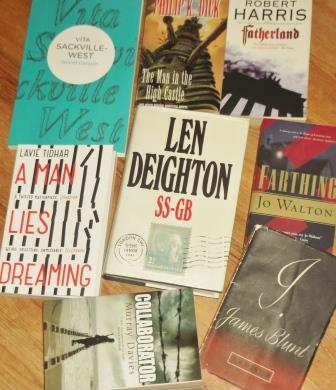

Future Imperfect

I recently

found myself in a keen discussion with an erudite crime fiction fan on

thrillers with settings which involved an alternative version of the history of

World War II. The discussion was prompted by news of an American television

adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s sci-fi classic The Man in the High Tower

and that a script had been commissioned by the BBC for a film of Len Deighton’s

marvellous thriller SS-GB.

It was Len

Deighton who told me of one of the earliest examples (possibly the earliest) I, James Blunt, a novella

by travel-writer H.V. Morton published in 1942 and now really quite rare. It

has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with the popular heart-throb minstrel

of the same name, of course. The James Blunt in question is a 61-year-old retired

tradesman living in a Surrey village five months after ‘The Capitulation’ when

Hitler won the war and leafy Surrey became part of ‘German England’.

The novella

takes the form of a diary, written in secret by James Blunt, covering the

period September 1944 to January 1945. Blunt is no action hero – in fact there

is virtually no ‘action’ in this 56-page story, but there is suspense and a growing

atmosphere of fear and suspicion generated by the fact that this most English

piece of England is being “Germanised” – or rather Nazified as news is replaced

by propaganda, rumours abound, people disappear or are deported to work in

Europe, children attend kindergartens which follow a Nazi curriculum and when

the postman delivers the mail he does so with a “Heil Hitler!”. Worst of all is

the total paranoia of the consequences of being caught helping a fugitive from

the occupying forces as in all probability it would involve being betrayed by

one’s own neighbours.

I, James

Blunt is,

in effect, a patriotic rallying cry. The ‘diary’ ends suddenly and dramatically

- just as Blunt, late one night, is considering destroying it as its very

existence is now a crime, there is a knock on his door… And then comes a

‘dedication’ from the author reminding “all complacent optimists and wishful

thinkers” that the war was (in mid-1942) still far from won and with warning

that “the scientific extermination of British nationality would be the first

act of a victorious Germany”.

At about the

same time as H.V. Morton (who had reputedly said in early 1941 that “Nazism has some fine qualities”!), an author

who was to be better known as a poet and gardener, Vita Sackville-West, was

also busy producing a cautionary ‘what if’

version of contemporary history.

Grand Canyon, which was

also published in 1942 (and which I have seen in a Sackville-West bibliography

described as “an awful novel”) is set in a world where Germany has defeated

Britain and America has ‘satisfactorily concluded’ its own war with Japan and

centres on the residents (emigres and refugees) of a hotel near the Grand Canyon,

over which the US Air Force is conducting manoeuvres. The moral here is that

the war is not over and, as the author attempts to show ‘the terrible

consequences of an incomplete conclusion or indeed any peace signed by the

Allies with an undefeated Germany…’

More

recently, in 2014, Israeli-born sci-fi and fantasy author Lavie Tidhar produced

A

Man Lies Dreaming, which has been described as “a twisted classic” –

and I think it is.

The

alternative historical set-up here is that the Communists take power in Germany

in 1933, dismantling the Nazi party and exiling the Nazi hierarchy, many of

whom move to England, including its former leader, ‘Wolf’, who becomes, by

1939, a private detective! In a wonderfully clichéd noir plot which involves Jewish gangsters, white slavers, an

American plan to destabilise communist Germany (and Russia) and a Nazi-inspired

Jack the Ripper roaming the streets, this is dark, dark matter – and in places,

caustically funny. Wolf, the detective who does good mostly by accident, is a

repulsive figure and gets satisfyingly beaten up and graphically tortured on

numerous occasions before facing a fate (for him) worse than death, and it is

all done in the best/worst possible taste in the tradition of a classic pulp

novel.

Which is the

point, really, as the titular man who lies dreaming is Shomer, a writer of

Yiddish pulp fiction in the 1930s (based on a real writer); a prisoner in

Auschwitz and the misadventures of Wolf pounding the mean streets of London are

his revenge.

For lovers of

black literary humour, this book is a must, if only for the scenes where Wolf

the penniless author of Mein Kampf

rages at his agent (Curtis Brown) for not getting him a deal on the sequel and

then has to be ejected from a literary soiree by Leslie Charteris and Evelyn

Waugh!

A Man Lies

Dreaming, I, James Blunt and Grand Canyon cannot really be

classed as conventional thrillers, though more recent attempts to twist the

tail of history certainly can and Robert Harris’ Fatherland, Jo Walton’s Farthing

series, Murray Davies’ Collaborator,

C.J. Sansom’s Dominion, D.J. Taylor’s The Windsor Faction and Guy

Saville’s recent ‘Afrika Reich’ novels have all been thought-provoking and

exciting additions to the genre.

Yet it is, as with The Man in the High Castle, to the field of science-fiction that I return to promote one of my favourite slices of alternative history, this time Nazi-free, the 1968 masterpiece Pavane by Keith Roberts, which depicts an England (specifically Dorset) where the Catholic Church has dominated life (restricting science, technology and progress) ever since the assassination of Queen Elizabeth I in 1588!

This is a novel of interlinked stories, almost a tapestry of stories, set in a 1968 where the main form of transport is a wagon train pulled by steam traction engines and crossbows are the favoured weapon. It is highly imaginative, exciting and almost certainly still in print somewhere.

|

|

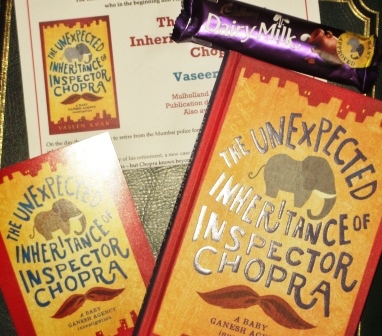

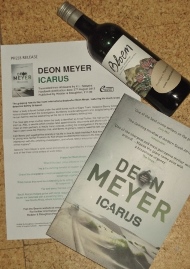

Decisions, Decisions

I have already commented this year on promotional gifts from publishers which accompany new novels and last month these posed a difficult dilemma for me. My advance copy of Vaseem Khan’s The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra arrived with a bar of ‘Elephant Approved’ chocolate whilst a proof of Deon Meyer’s new thriller Icarus came accompanied by a half bottle of South African wine. Hmmmm…which to read and glowingly review first?

Icarus, published by Hodder later this month, is the latest case for Deon Meyer’s outstanding cast of diverse South African policemen revolving around lead detective Benny Griessel and part of the plot is set in the South African wine industry. Hence the sample half bottle (did I mention it was only a half?) which proved vital for my background research and understanding of this crucial component of the novel.

Now fans of this superb series will know that the flawed, but doggedly heroic Benny Griessel has had his problems with alcohol in the past and after 602 days sober, he falls off the wagon (well, jumps rather than falls) in the most heart-wrenching circumstances. Whilst Benny fights his own demons, his elite unit of detectives – ‘The Hawks’ – investigate the murder of a whiz-kid internet entrepreneur who provides alibis for unfaithful partners who naturally want to keep their activities secret. (Not beyond the bounds of possibility given recent revelations about the databases of certain ‘dating sites’.)

The plot unfolds (very cleverly) on parallel tracks, though Benny’s personal struggle is never far from the surface, and the police procedure seems bang up-to-date. As usual, the writing is elegant and intelligent, proving - if further proof is needed - that Deon Meyer is at the top of the crime writing tree when it comes to novels of ensemble police investigations. I would hazard that only Michael Connelly and Ian Rankin, on their day, now compare.

When it comes to fictional Indian policeman, I have always had a soft spot for Inspector Ghote, of Bombay CID, as created by the late Harry Keating. (And as a reviewer, Bribery, Corruption Also is one of my favourite ever titles.)

But now Bombay is Mumbai and there’s a new detective in town, Inspector Ashwin Chopra, courtesy of Vaseem Khan, making his debut with The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra from Mulholland Books this month.

At the start of the book, Chopra is facing his last day as a policeman before (early) retirement and by the end has established a private detective agency with a rather unusual – but very resourceful – partner, a baby elephant called Ganesh, the unexpected inheritance of the title. Not being a natural elephant-handler and living in a high-rise block of flats, Chopra rather charmingly visits the elephant section of the largest bookshop in Mumbai yet none of the self-help texts he consults can explain why his new companion is not eating properly. The reason eventually becomes clear and explains the promotional item of a bar of ‘Elephant Approved’ Cadbury’s Dairy Milk…

Watching the Writers Write

I remember being told the story of John Creasey, the founder of the Crime Writers’ Association, proposing a publicity stunt to promote detective stories by offering to sit in the window of Selfridges for a week writing a novel (and he would have written one in a week) in full view of the passing shoppers.

Needless to say, the idea was greeted with horror by most members of the CWA and Creasey was discouraged from making crime writing look too easy.

Now former CWA Chairman Russell James is using the jolly old interweb to do something similar. He has just started writing a new novel and intends to keep a weekly online diary telling how he and the novel are progressing. He bravely offers this open window into ‘what a writer does all day’ at https://russelljamesbooks.wordpress.com/ though I doubt if I will have time to consult it unless I can find a spare moment between Bargain Hunt and Countdown…

Noir – the New Black

I was asked recently by a (frighteningly) young crime writer what the definition of “noir” was and I mumbled something along the lines that, in a novel, it is when you know from Chapter One that it’s not going to end well.

I then remembered that the late Derek Raymond always referred to his gritty crime novels as his “black books” and thought I would ask a couple of other writers whom I also consider to be skilled noiristas.

Interrupting Russell James, the author of British noir classics such as Underground and Payback, just as he starts work on a new novel (see above), he gave me the following off-the-cuff thoughts:

Noir fiction is not the same as hard or hard-boiled or violent fiction. It isn’t necessarily fast-moving – though it tends to be, more often than not. In a noir novel the doomed hero (either gender but let’s be honest, usually male) is out of luck, trapped in a no-way-out nightmare, possibly of his own making (as in Greek tragedy) and, whatever he does, nothing can stop the walls from closing in.

That Irish scamp, and a true poet of noir Ken Bruen had a day or so to think about it and came up with:

Noir is the tunnel at the end of the light.

The 1999 Oxford Companion to Crime and Mystery Writing offers an essentially American definition:

Fiction Noir (sic) depicts the controlled depravity and existential absurdities face by men and women caught in a web of random violence, amorality, and lust for sex and money. This bleak view of life is a result of the Great Depression, where personal ethics and ability were co-opted by forces totally beyond the control of the individual.

As a writer who has never really considered himself more than ‘soft-boiled’, I find this an interesting question and would be interested to hear any other definitions.

Old Friends

It is always good to renew old reading friendships, either with authors or with characters.

I am particularly looking forward to reading Ted Allbuery’s The Dangerous Edge, which I found in a charity bookshop and which I had never seen before. If it is half as good as Allbeury’s classic The Lantern Network, I will be well-pleased. I always thought that former Intelligence Officer Ted Allbeury (1917-2005) was under-appreciated as both an excellent constructor of spy fiction plots and as a fine writer who was outstanding at portraying the sadness of betrayal.

Fans of Leslie Charteris’ character Simon Templar, alias ‘The Saint’ – and there have been and still are millions of them – are well aware of the long-running series of books and stories as well as film and television incarnations. Yet it is radio which has been the most durable medium for The Saint. From the first series during World War II to the most recent in 2002, fifteen actors have played the modern-day Robin Hood, probably the most high-profile and longest-running being the late, great Vincent Price.

Now Ian Dickerson’s new book The Saint on the Radio (Purview Press) goes behind the scenes, and the microphones, to provide details of radio series, writers, cast-lists, episode synopses and two complete radio scripts. Surely enough to satisfy the most ardent fan.

Fantastic Firenze

If you have no intention of visiting Florence this summer, you have my sympathy. If you have never been there, you have my pity. Yes, it can be hot and crowded, some of the “traditional” leather jackets may be of dubious origin as well as over-priced, and it has hundreds of street traders who do not seem to realise that a gentleman of advancing years such as myself has absolutely no need of a “selfie stick” – whatever that is.

Still, it is Florence, a city of outstanding beauty and fascinating (and violent) history, and if you can’t get there the next best thing would be to read David Hewson’s splendid new thriller The Flood, which is out now from Severn House.

David Hewson is a thriller writer who seems, early in his career, to have signed a deal if not with the Devil, then at least with Thomas Cook. In a distinguished writing career, David has set his bestsellers in Shanghai, Spain, Rome, Denmark, Amsterdam and now Florence, though as far as I know he has yet to exploit the location of his home town of Bridlington on the East Yorkshire coast.

The Flood is set in a quite brilliantly portrayed Florence in 1986 and starts with an investigation, by a distinctly unhealthy Italian policeman and an English female academic, into a series of attacks of works of art, but of course things don’t stop there. Far darker crimes are taking place and relate back to the disastrous flood which ravaged the city twenty years before, in 1966.

Coming Up

I do hope the following three authors do not take offence at being labelled “big beasts” but in the crime-writing business in the UK, that is exactly what they are – and all have new novels out over the next few weeks.

A Game For All The Family, out this month from Hodder, is Sophie Hannah’s twelfth novel and her first since she adopted the spats and moustache-straighteners of Hercule Poirot in The Monogram Murders last year. Coincidentally, her new psychological twister is set largely in Devon, which everyone knows was Agatha Christie territory and often the stomping ground of a certain Hercule Poirot.

It wouldn’t really be September if there wasn’t a new Dick Francis novel and though Dick is no longer with us, his son Felix splendidly carries on ‘the family business’ and Front Runner will be published by Michael Joseph on 7th September.

In the same week, Macmillan release a new ‘Vera’ novel or, more correctly, the seventh DCI Vera Stanhope adventure in The Moth Catcher by Ann Cleeves, set in the deceptively quiet and suspiciously peaceful Northumberland community of Valley Farm.

Cosmopolitan Crime

If proof were needed that crime fiction is truly cosmopolitan (and this month’s column alone mentions locations including the UK, US, Italy, Norway, New Zealand, Poland, India and South Africa), then I present in evidence the first Liberian crime novel – or at least the first I have come across.

Bound To Secrecy by Vamba Sherif (published by Hope Road) is set in the remote Liberian border town of Wologizi and is written by a man who aptly defines the word ‘cosmopolitan’. Born in Liberia and brought up speaking several local languages, journalist and film critic Vamba Sherif moved to Kuwait for his teenage education and did his earliest writing in Arabic. The first Gulf War forced a move to the Netherlands where he is now based and his work has been published in Dutch, French, German and Spanish as well as English.

The Picture Not in the Attic

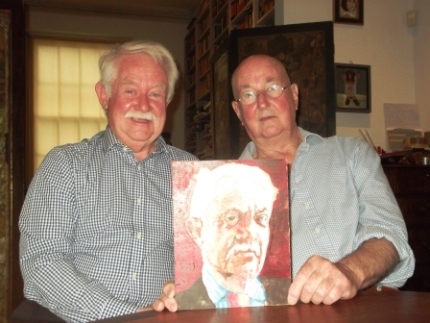

I have heard tales of authors who stick pins in Voodoo dolls of their editors, but never before had I come across an author offering to paint a portrait of their editor, until now, that is. It helps, of course, if the author in question is an accomplished artist.

} }

Last year I had the pleasure of editing, for Ostara’s Top Notch Thrillers imprint, a new edition of Reg Gadney’s 1971 novel Somewhere In England and later this year, Ostara will republish Reg’s debut spy thriller Drawn Blanc from 1970.

Now I knew that Reg Gadney had combined two successful careers – as an art teacher and artist and as a writer of novels, non-fiction and TV and film scripts – but had not realised that he had such an impressive reputation as a portrait painter. As we worked together on republishing his books, Reg and I became friends and when he offered to immortalise me in oils, it was an offer I could not possibly refuse.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|