|

The Weekly Grind

At the start of this century I vowed that I would limit my visits to London to no more than one a week. It was not that I had fallen out of love with the city, far from it, but for a gentleman of my frailty and advancing years, I find it difficult to cope with the ever-changing brands of rather thin and sour ale offered at exorbitant prices in the local hostelries and the constant buffeting by the millions of pedestrians who appeared to be surgically attached to mobile phones.

Therefore it was with some trepidation that, in one week in August, I journeyed up to town on consecutive days to answer the calls of a ravenous media.

Naturally, I was on my best behaviour when I reported to the BBC’s Old Broadcasting House to be interviewed by the legendary Jenni Murray for Woman’s Hour on the topic of crime writer Margery Allingham. The feature was part of a series done by the programme to celebrate female writers from the ‘Golden Age’ and only a week previously I had much enjoyed Seona Ford and Jill Paton Walsh discussing Dorothy L. Sayers. To represent Margery Allingham, the BBC chose myself and the far better qualified Julia Jones, Margery’s biographer. As Julia was on holiday, sailing one of her luxury yachts around the East Anglian coast, she made her contribution ‘down the line’ from a studio in Norwich, leaving me to face the awesome Jenni alone.

Fortunately, Jenni and I had worked together before when we served as judges for the CWA’s Gold Dagger award and even though that was over ten years ago now, she graciously admitted that she remembered me.

A mere 24 hours later I was in London again, to be interviewed again, but this time about my new collection of short stories Angels and Others (Telos Books) by Tim Haigh by his The Books Podcast and in a more basic, but far more congenial studio, the upstairs bar of The Two Chairmen just off Trafalgar Square.

Once again, I knew my inquisitor for not only had Tim interviewed me for the podcast (www.bookspodcast.com) before, but we first met 25 years ago when he, as a young radio reporter for LBC, covered the launch of A Suit of Diamonds, the anthology which marked the Diamond Jubilee of Collins Crime Club.

And after such an exhausting day, what better way to relax than to help the talented Sophie Hannah celebrate the launch of her new novel A Game For All The Family, published by Hodder.

Baffling the Fan

One of the benefits of the jolly old interweb is that it is much easier to track down rare and scarce second-hand books than it ever was. Of course, one misses the sheer physical pleasure of rooting around atmospheric second-hand bookshops, something I have never been able to resist even when travelling in foreign lands where I do not read the local language (and so few books seem to be printed in Latin these days). There is, however, a major downside to buying “online”, as I believe the young people call it, in that one never actually sees or holds a book before one buys it.

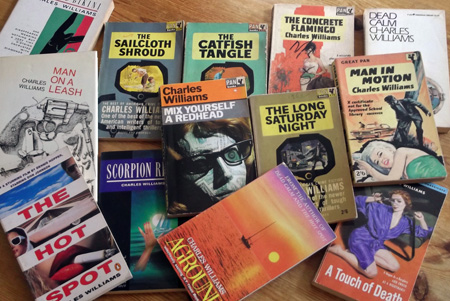

I was painfully reminded of this when, last month, I decided to add to my collection of thrillers by that supreme craftsman of suspense, Charles Williams (1909-1975), a writer I have long admired and recommended to any would-be student of the hardboiled. In the rush of enthusiasm I always get when thinking I have discovered titles by a favourite author which I have not read, I clicked the appropriate buttons and, a few days later, found myself the owner of three Williams novels – two of which I already possessed.

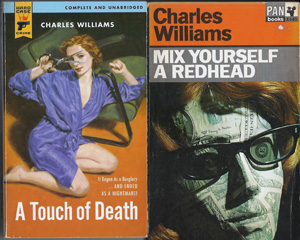

I was aware that many of Williams’ books had been filmed (famously Dead Calm) and in that process, some had been retitled; for example Hell Hath No Fury became The Hot Spot. I was not, unfortunately, aware that his 1953 novel A Touch of Death, so recently reissued in the splendid Hard Case Crime imprint, had been retitled for the UK Pan edition in 1967 as Mix Yourself A Redhead.

Even more confusingly, I purchased Confidentially Yours (a 2014 reissue) not realising I already owned the 1962 original version The Long Saturday Night but I fortunately had resisted the opportunity to buy Finally, Sunday! – the same book but retitled to coincide with Francois Truffaut’s French film version Vivement Dimanche!

I sincerely hope that an old man’s confusion does not dissuade anyone from discovering Charles Williams, who really could deliver a tense, well-plotted and believable thriller, often with a nautical background (he was very good on the Gulf Coast area and Florida), and usually in less than 180 pages. Even fifty years on, his work could teach the authors of many of today’s overblown thrillers a thing or two.

There is a postscript to my Charles Williams saga, which will probably be of little interest to anyone but me. I have discovered that Williams (Charles) wrote the script for the 1968 movie adaptation of Snake Water by English writer Alan Williams, an excellent adventure story which I had the privilege to bring back into print as a Top Notch Thriller a few years ago.

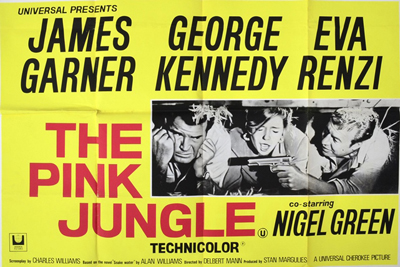

The film, rarely seen then or now, was “Hollywoodised” and a tense, violent treasure-hunt thriller set in the jungles of South America was turned into a “romantic comedy” starring James Garner and retitled The Pink Jungle.

I somehow think that was not Charles Williams’ finest hour, but please don’t let that put you off his novels.

Buon Compleanno

What do you give the acknowledged Godfather of Italian crime fiction on his 90th birthday? Why, a book of course, and that’s just what his UK publisher Mantle have done.

Blade of Light, his nineteenth Inspector Montalbano novel, is to be published to mark Andrea Camilleri’s birthday this month and I know his many fans here will join me is wishing him Buon Compleanno.

Academic Texting

In order to keep up my academic study of crime fiction in those longeurs between books by the eminent Professor Barry Forshaw, I have spotted a couple of titles which may well find their way on to a shelf in one of the libraries here at Ripster Hall.

Out now is Kate MacDonald’s Novelists Against Social Change: Conservative Popular Fiction 1920-1960 (Palgrave Macmillan) which examines the work, among others, of John Buchan, whose influence on the British thriller was considerable and whose legacy is still being enjoyed in sell-out performances of the hysterically funny play The 39 Steps.

Expected in March next year from the University of Wales Press is Crime Fiction in German – Der Krimi by Katharina Hall, which will surely fill a gap in European crime-fiction studies. I am aware of studies of French, Italian and Scandinavian (enough, already) crime-writing but have not come across (in English) a decent survey of German “krimis”. I am particularly looking forward to the Humour in German Crime Fiction chapter as surely there must be one…

My only caveat to heartily recommending these books (apart from the minor fact that I haven’t read them) is their price. The serious student will have to fork out £55 for Novelists Against Social Change and £24.99 for Crime Fiction in German. It seems that a little learning costs quite a lot these days.

Added Value

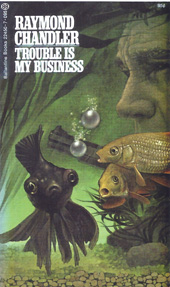

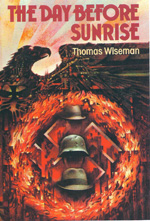

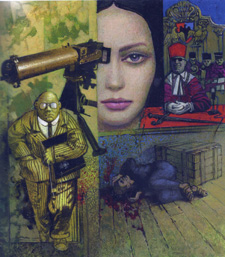

If, as a reader, you are seeking value-for-money then you won’t get more bangs for your buck than in the superbly produced Tom Adams Uncovered (HarperCollins, £25), a splendid celebration of a cover artist who has proved that you can tell a book from its cover, if it’s a good one.

Born in Rhode Island, but currently living here in Cornwall, artist Tom Adams has worked in many fields – advertising, film, posters, album covers – but is probably best known for his work in publishing, particularly for his innovative, and sometimes startling, covers. Most familiar, I suspect, to readers of this column (though they may not recognise his name) will be his work on Agatha Christie titles for Fontana paperbacks in the period 1962-1979.

What I was not aware of until now, was just how many other iconic covers Tom Adams has been responsible for, particularly his work on the novels of John Fowles, David Storey, Joan Fleming, Peter Straub, Sue Grafton, Raymond Chandler and Thomas Wiseman.

I have lost count of the number of crime novels I receive each year with the now very hackneyed ‘man-walking-away’ design (or, more recently, ‘woman-in-a-coat (usually red)-walking away’) and it makes me swoon in admiration at the care and imagination Adams applied to his work – and all credit to the publishers who allowed him to do so. I was delighted to find in this retrospective, some of his artwork for Fontana paperback editions of Eric Ambler’s fabulous thrillers, several of which I have owned and cherished for almost fifty years and whose covers, in my not so humble opinion, have never been bettered.

Eminent Victorians

This column began life, almost twenty years ago, on printed paper in the Sherlock Holmes Detective Magazine, a journal dedicated (mostly) to the great consulting detective and his adventures. The magazine had an “and finally…” end-piece column which if memory serves was called I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere (though that is now the name of a website resource run by dedicated fans). I am reminded of that phrase this month dueto the numerous Sherlockian or late Victorian connections coming up in the world of crime fiction.

On the 10th, Bonnie MacBird’s take on the great detective, Art in the Blood (delightfully published in a revived Collins Crime Club imprint) is celebrated by an appearance of the author at Westminster Reference Library, on St Martin’s Street in the heart of London’s West End. Bonnie, a film development executive and screenwriter based in Hollywood (although most of the book she admits was written in the Sherlock Holmes hotel on Baker Street), will discuss the research which went in to Art in the Blood and her sources of inspiration. Tickets to the event, hosted by Westminster Library’s in-house Sherlockian expert Catherine Cooke, are free but should be booked in advance via:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/art-in-the-blood-a-historical-novel-case-study-tickets-17965647736

Art in the Blood is set in post-Ripper London, Lancashire and Paris, where Holmes and Watson meet a French detective called, rather cheekily, Vidocq. Art, ‘artistes’ and blood are all involved, as the title suggests, and when it comes to blood, literally so when Watson gives his all for his friend. But then, dammit, he is an English gentleman and a stout fellow, so what else should one expect?

I do not claim to be anything of a Sherlockian scholar myself, but Bonnie MacBird’s novel seems to me something of a class act among the many thousands (no exaggeration) of Holmesian pastiches or parodies published since the death of Arthur Conan Doyle in 1930, although the first of them, I believe, appeared as early as the 1890s when both Holmes and Doyle were very much alive and kicking – in publishing terms, that is. {I am aware of two being published this month, both from Titan Books, James Lovegrove’s Sherlock Holmes The Thinking Machine and Mycroft Holmes by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.}

To fill in the many gaps in my knowledge, what I really needed was an Everything You Wanted to Know About Sherlock Holmes But Were Afraid To Ask sort of book. Fortunately, I have found one in B.J. Rahn’s excellent study The Real World of Sherlock (Amberley Publishing), which looks at both the fictional creation and the real world of criminal investigation in which he operated.

Although many of the elements behind the creation of Holmes the character are well-known, Rahn elegantly marshals her material and neatly weaves together the various elements: Doyle’s debt to Edgar Allan Poe’s pioneering detective stories, his own fascination with crime and seeing justice done, and the inspiration of his medical tutor Dr Joseph Bell. This latter fact I knew full well having once been given a fascinating lecture on the subject by that most charming of actors, the late Ian Richardson, who was immensely proud of having portrayed both Holmes and his ‘mentor’ Bell. {And who, incidentally, was an early candidate for the television role of Inspector Morse.}

However, much of the attraction of The RealWorld of Sherlock comes in the utterly fascinating sections on the Metropolitan Police and the contemporary advances made in the detection of crime. I had no idea, for instance that the science of fingerprinting could be traced back to the University of Breslau in 1823 or that Charles Darwin was (albeit indirectly) involved in the use of fingerprints in solving a crime in Argentina in 1892, nine years before the technique was adopted by Scotland Yard.

There is a fantastic amount of detailed research on display here, cataloguing the influences on Conan Doyle as he was creating his iconic hero, yet the book gives due credit to that unquantifiable element, Doyle’s own imagination and skill at characterisation. All crime writers everywhere (except the incredibly arrogant ones) know that the real legacy of the Conan Doyle was to bequeath them not just Holmes, but that most excellent, stalwart other half of the double act – Dr Watson.

|

|

Both Art in the Blood and The Real World of Sherlock make reference to the killing spree of Jack the Ripper, whose unsolved crimes still have the power to shock more than 125 years later. Indeed, just as Sherlock Holmes has inherited a staunch following of dedicated ‘Sherlockians’ so there are ‘Ripperologists’ who study every aspect of the spate of unsolved murders which centred on London’s East End in 1888 (and arguably beyond).

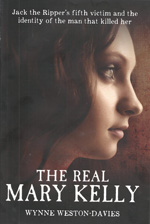

Now a new book, The Real Mary Kelly (Blink Publishing) by Wynne Weston-Davies sheds new light on the identity of the Ripper, but more importantly on the identity of his fifth (and some would say not final) victim known up until now as ‘Mary Jane Kelly’.

I say ‘up until now’ because after years of research, Dr Weston-Davies, a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, has made a very good case that Mary Kelly was actually Elizabeth Weston Davies, his great aunt, and goes on to speculate on the identity and motives of the Ripper.

I first learned of Wynne’s research in 2012 when he told me he had discovered something of a ‘black sheep’ in his family history. At the time, we were working on getting the novels of Wynne’s father (and Elizabeth’s nephew) back in print, his father being better known under the pen-name Berkely Mather.

Although he, rather strangely, does not rate a mention in The Real Mary Kelly, Mather (John Evan Weston-Davies, 1909-1996) was an accomplished writer of early television dramas and radio serials in the 1950s, of adventure thrillers such as the classic The Pass Beyond Kashmir, historical novels and film scripts (including Dr No) as well as serving as Chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association.

It was his father’s reluctance to discuss his family history and hints that there was “a dark secret” lurking there that initially set Wynne Weston-Davies on his quest. It turned out to be quite a spectacular secret and certainly very dark.

In his book, Wynne puts forward the case that his great aunt Elizabeth left her Welsh home in 1881 to work first as a lady’s maid, then in a high-class Bloomsbury brothel and finally as a prostitute in the East End, where she adopted the names Mary Jane Kelly or sometimes Marie Jeanette Kelly until her gruesome end, aged 25, in Room 13, Miller’s Court, Dorset Street in November 1888.

In their 1995 book The Lodger, two eminent Ripperologists, Stewart Evans and Paul Gainey, stated that Mary Kelly “Of all the (Ripper) victims...is the most mysterious. It is not even certain that Mary Kelly was her real name. Genealogical researchers are still trying to positively identify her and her family.”

I think The Real Mary Kelly closes that particular chapter, making a convincing case for Elizabeth being Mary and for Elizabeth’s dark reputation within the family if she had indeed, as is suggested, adopted prostitution as a career both voluntarily and with enthusiasm. Where Wynne’s book is less convincing is his extrapolation on the identity of Elizabeth’s infamous murderer, introducing (I think) an entirely new suspect.

The identity of Jack the Ripper is a debate which will run and run, but if Wynne’s conclusions are correct (and I believe DNA tests could be possible) then at least one of his victims can now be accurately laid to rest.

My Word is MyBond

For some reason, and I genuinely do not know why, I have never been sent any of the ‘celebrity continuations’ of the adventures of James Bond to review. Clearly I must have done something to upset the Ian Fleming Estate pre-2008 when Sebastian Faulkes and subsequently Jeffrey Deaver and William Boyd picked up where Kingsley Amis, John Gardner and Raymond Benson had left off.

This month sees Anthony Horowitz adopting the role of the man with the golden typewriter with his entry into the Bond canon, Trigger Mortis from Orion and a fellow critic has taken pity on me and slipped me his review copy.

I had heard some disquiet about the title when it was announced earlier this year, some commentators finding the sound of Trigger Mortis a little too cheesy for their refined taste. Having read the book, it doesn’t worry me in the slightest as in context it makes perfect sense and overall I thought the book a ripping yarn and a fitting homage to the Bond of the printed page, especially enjoying the cheeky opening line: It was that moment in the day when the world has had enough.

Trigger Mortis is respectful, almost too respectful, of its position in Bond chronology, being set almost immediately after the action finishes in Goldfinger (and if you want to know whatever happened to Pussy Galore, or why leopards never really change their spots, this is the book for you). There are numerous references to the Goldfinger case, but also to events in Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, Moonraker, Diamonds Are Forever and Dr No, although not (unless I missed it) in From Russia With Love.

What is slightly strange is that given the villain in Trigger Mortis is a rich, mad Korean called Jason Sin (and a pretty good Bond villain he is too), there is no mention made of Bond’s very recent lethal encounter with another Korean, Oddjob, whom he encouraged to leave a pressurised aeroplane by somewhat unconventional means.

Still, there’s plenty of action, swift changes of scene, a sadistic foreign villain with an imaginative way of deciding the fate of his victims and some set pieces Fleming would have been proud of. Fans of Top Gear will love the scenes on a certain German race track and aficionados of Bond trivia will delight in the knowledge that Anthony Horowitz based those Nürburgring scenes around Ian Fleming’s story outline Murder on Wheels – an outline for an episode of a television series which never got made, being superseded by the success of the film of Dr No.

Anthony Horowitz has done a good job of distilling and bottling the essence of James Bond the rather thuggish man-of-action, and wisely keeping him positioned in his 1950s heyday and I am sure Trigger Mortis will be a success. The only question remaining is who will write the next one. J. K. Rowling? I don’t know what the odds would be on that, but Bond would.

Resurrections

This year has seen something of a flood (at times in seemed like a tsunami) of reissued “classics” – at least according to their editors – from the ‘Golden Age’ which is usually accepted as being the period between the two World Wars. The British Library’s publishing arm have built up a large catalogue of attractively-packaged titles, Allison & Busby have revived the thrillers of Alexander Wilson and Dean Street Press have recently reissued a series of ‘Bobby Owen Mysteries’ by E. R. Punshon (a writer oft-praised by American critic Anthony Boucher), including Crossword Mystery.

Now HarperCollins has gone one better and resurrected an entire imprint, The Detective Club, initially launched in 1929 and an immediate forerunner of the more famous Collins Crime Club (the two imprints merged in 1934). The idea behind the Detective Club was to produce inexpensive hardback editions of existing “classics” with contemporary titles. In the 1920s, that meant established names such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Wilkie Collins, Edgar Wallace and Freeman Wills Croft rubbing shoulders with newcomers such as Agatha Christie, and all packaged in extraordinary jackets which the new editions faithfully reproduce.

Among the launch titles is one I have never read but have read much about. Originally titled The Big Bow Mystery in 1892 but retitled when filmed in 1927 as The Perfect Crime, Israel Zangwill’s famous novel is credited as the very first ‘locked room mystery’.

Now I know the Puritans among us will immediately cry “heresy” and claim that Edgar Allan Poe’s Murder in the Rue Morgue from 1841 was the first. Well, of course Poe’s was the first short story in the sub-genre but then, a mere fifty years later, Zangwill wrote the first full-length novel.

For those who wish to compare and contrast these two undoubtedly pioneering works, the new Detective/Crime Club edition of The Perfect Crime contains them both, and for £9.99, you really can’t argue with that.

September Picks

September was the seventh month (Lat. septem) in the old Roman calendar and on that rather flimsy excuse, I give you seven crime novels which you will, or should, be reading between now and St Michael’s Day which, coincidentally, marks the 85th birthday of my old mess-mate (Lat. contubernalis) Colin Dexter.

Mention of Colin brings to mind fond memories of birthday tea-parties (we share the same birthday) in Oxford and I could not help but notice that Alex Howard’s latest ‘DCI Hanlon’ novel, A Hard Woman To Kill (Head of Zeus) features scenes set in “an exclusive brothel in Oxford”.

Like a rather well-known Oxford detective, DCI Hanlon does not appear to have a first name - at least not yet. However, we may not have to wait long at the rate Mr Howard is writing books as this is his second novel in six months. No wonder, when you Google him, his website teases you with the question: “Ever wondered what makes a great crime writer? Find out at…”

It is a question that has plagued me for years.

I have always said that Michael Ridpath, with his ‘Fire and Ice’ series set in Iceland, was one of my favourite Scandinavian crime writers, but of late his books have taken a historic twist, giving us his take on the early months of WWII. Starting with what is known now as ‘the Venlo incident’ and involving the Duke of Windsor (him again) and the shaky start to Winston Churchill’s wartime government, Shadows of War [also from Head of Zeus] is the second Ridpath novel (following Traitor’s Gate) is a sequence which promises to develop into a quality series.

If I am allowed a slight niggle – and I usually am – it is that Shadows of War is promoted as a spy novel set during “The Phoney War” on the western front (September 1939 to May 1940) when nothing much happened. Now I am sure I have read somewhere that at the time that lull-before-the-storm period was known, at least in England, as “the Bore War” and that the phrase “Phoney War” was an American description coined in around 1942.

Although I have not been invited to a meeting of the East Anglian Chapter of the Crime Writers’ Association (like Hell’s Angels, members appear without warning at secret locations on their motorbikes) for almost a quarter of a century but I still feel a loyalty to crime writers who ply their trade in the Eastern marches.

Jim Kelly lives in Ely, famous for its “battleship of the Fens” cathedral, and is a bit of a wizard at describing the north Norfolk coast and the fenlands which drain into it. (He has long said that Dorothy L. Sayers’ The Nine Tailors was a formative influence on him.) He’s also rather good at police procedural mysteries. Death On Demand (Severn House), starring his excellent detective duo of Shaw and Valentine, centres on the murder of a Care Home resident on her 100th birthday at the same time that local police resources are stretched by the influx of religious pilgrims to Walsingham, sometimes known as ‘Norfolk’s Nazareth’.

From the wilds of Norfolk, the award-winning Barbara Cleverly takes us to the arguably wilder setting of Cambridge and does so over three distinct time frames in her short story collection The New Cambridge Mysteries (from Ostara’s Cambridge Crime imprint).

Cleverly is best known for her Joe Sandilands historical mysteries and I remember Maxim Jakubowski, the crime guru of the Charing Cross Road, enthusing profusely about his debut appearance in The Last Kashmiri Rose in 2001. Although having the good sense to be born in Yorkshire, Barbara Cleverly has lived and worked for many years in East Anglia and knows Cambridge well. Her new anthology features six stories all set in and around the city in ‘Cambridge Past’ (1922), ‘Cambridge Present’ and a very dystopian ‘Cambridge Future’ of 2022 which, come to think of it, isn’t that far away…

Words such as ‘iconic’, ‘legend’ and ‘classic’ get bandied about more than they probably should when it comes to crime fiction and I know I am just as guilty as the next intelligent and discerning reader. However, when I declare that Jane (Prime Suspect) Tennison (aka Dame Helen Mirren) is a true icon of British crime fiction, who will disagree with me? More to the point, who will disagree with her creator, Lynda La Plante? (I’ve met her, and I wouldn’t.)

Tennison (Simon & Schuster) is the much-anticipated prequel to Prime Suspect, where we meet 22-year-old WPC Jane Tennison, fresh out of Hendon Police College, pounding the mean streets of 1970’s Hackney. This is a big (580 pp), meaty book which, like Jane Tennison, takes few prisoners (except those she’s legally obliged to).

And, okay, I’m cheating now, but I have already got my copy of Get Even by Martina Cole (Headline) and I predict this will be a September best-seller (on pre-orders alone) despite the fact that it isn’t actually published until 6th October.

Amazingly, for one so young, Martina has been in the crime fiction business for twenty-two years now, and always at the top making her one of the, if not the, most successful British crime writer of recent times. It seems strange then, that she has not (as far as I am aware) been “elected” to the Detection Club, nor made Chairperson of the Crime Writers’ Association. Surely, as we used to say in Fleet Street, some mistake?

And now I’m really pushing it, because Ian Rankin’s Even Dogs In The Wild is not actually published by Orion until Novemberbut as I’ve already read it, I could not resist including it. Naturally I am sworn not to reveal too much, but I note that Police Scotland is currently looking for a new Chief Constable and on this outing I am happy to propose, should anyone ask me to, either of my favourite fictional police persons, John Rebus and Siobhan Clarke, for the post.

Knowing my luck, the successful candidate will probably be one of my least favourite characters, the tea-total Malcolm Fox, even though I did feel a slight twinge of sympathy for him in Even Dogs.

Fudge Off

I was not aware until now that there were at least eighteen ‘Hannah Swensen Mysteries’ centred on a bakery in small town Minnesota, each seemingly doubling as a recipe book in a sort of Murder She Baked series, the latest of which, by Joanne Fluke, is Double Fudge Brownie Murder from Headline. If you like a cosy mystery to read in between episodes of the Great British Bake Off, then this is for you, or you can just use it as a cook book because there are a lot (and I do mean a lot) of recipes in here, all calling for traditional American ingredients such as Skippy Creamy Peanut Butter, Schilling pork gravy mix, McCormick’s Imitation Maple Flavoring (sic) and Hebrew National hot dogs. Perhaps we will get some of these exotic foodstuffs over here once Rationing ends…

One thing could have been clearer, though, and that is the ‘Baking Conversion Chart’ provided at the end of the book to explain the American system of weights and measurements. The only problem is that the most-used measure in American baking is “the cup” and to offer the conversion rate that “1 Cup = ¼ liter” (sic) doesn’t really help that much if you’re measuring flour or sugar.

On reflection, I think I’ll stick to Mary Berry.

Told You So

Although I have absolutely no personal experience of something called the Ashley Madison website, I understand that the publication of its ‘database’ (whatever that is) has caused consternation in certain circles. Regular readers will appreciate that I warned them of such things when I reported, only last month, on the plot of Deon Meyer’s superb new thriller Icarus. I hate to say I told you so, but I did, as did Deon Meyer.

From A View to a Kill?

Like members of the Royal Family, the senior staffers at Shots Magazine never travel together on the same aeroplane and are rarely photographed together outdoors, where they could be overlooked and exposed to a clear field of triangulated fire.

So it was a rare occasion when a wandering paparazzo managed to snap the voluptuous Ayo Onatade, Mike ‘Tombstone’ Stotter and myself as we relaxed after a strenuous editorial meeting in the rooftop gardens of the Hachette publishing empire’s London headquarters.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|