Clubland Heroes

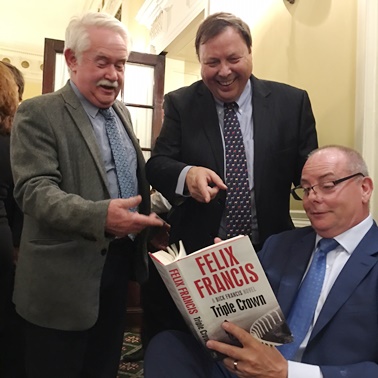

The social event of September was the

star-studded party held to celebrate the launch of Felix Francis’ new racing

thriller Triple Crown from his new publisher, Simon & Schuster, at

the Cavalry and Guards Club in London’s Piccadilly.

Set mostly on the American horse-racing circuit, the plot of Triple

Crown revolves around the attempt by the same horse to win three

long-established races - the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes and the

Belmont Stakes – in the same season, a feat rarely done. Naturally, this being a thriller from the

Francis stable, there is skullduggery and corruption involved and the amount of

drugs and performance-enhancing substances given to horses, if Felix’s research

is accurate (and I have no reason to think it is not), is enough to blow the

mind of a Russian athletics coach.

At one point I had to remind Felix that

he really shouldn’t be wasting his valuable time trying to help Shots editor Mike Stotter with some of

the long words in the book, but attending to his distinguished guests. Yet soon

after I found myself distracted, trying to explain the concept of winning ‘by a

head’ to a disbelieving audience of crime-writer Simon Brett and Crimefest organiser Myles Allfrey.

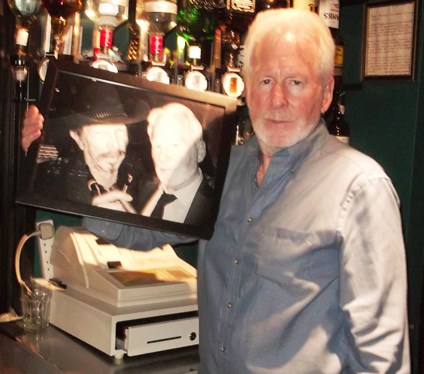

One of the disadvantages, these days, of

being only a ‘Country Member’ of a famous London club is that one is often

behind with the latest news and gossip. It therefore came as something of a

shock, on a recent visit to Gerry’s Club (the defibrillator always on hand

should Soho’s heart stop beating) to learn that American crime writer,

songster, satirist and would-be politician Kinky Friedman had been in the UK,

playing to packed-houses, this summer. And to prove it, Michael Dillon, the

guardian of Gerry’s, had a photograph showing him and the famous self-styled

‘Texas Jew-Boy’ together.

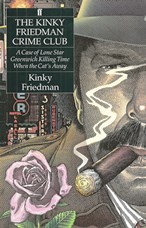

Younger readers may well be forgiven (though not by me) for not knowing

the name Kinky Friedman, but in the early 1990s his outrageous, and

outrageously funny, New York set crime novels

featuring himself as a wise-cracking, cigar-smoking, cat-loving

detective landed on an unsuspecting Britain. Kinky himself appeared at the legendary

1995 Boucheron convention held in

Nottingham, where he treated a slightly bemused, mostly British audience to

songs made famous by his country-and-western band The Texas Jewboys, rather

than give a talk about crime-writing.

I remember watching that performance, and observing the surprised faces

of the audience as Kinky walked in with a guitar rather than a book, from the

wings in the company of Sara Paretsky (who turned out to be a fan) and later

managed to get Kinky to sign a book for me, The Kinky Friedman Crime Club,

an anthology of three of his private eye novels.

I still have it, with the cherished

inscription ‘To Mike – from a Texas

Jewboy to a bluff North Countryman – from Kinky’ and signed with a Star of

David.

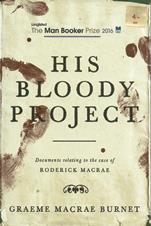

More Bloody Scots

Possibly the oddest thing about Graeme

Macrae Burnet’s splendid novel His Bloody Project is that it has

made it on to the shortlist for the 2016 Man Booker Prize and yet did not even

feature on the longlist for the Crime Writers’ Association’s Gold Dagger.

Burnet’s novel was published in late 2015 in the Contraband imprint of

small Glasgow publisher Saraband and purports to be an assemblage of documents

relating to the case of Roderick Macrae, on trial for a bloody triple murder in

Inverness in 1869. The central document in the novel (remember: novel) is an account written by Roderick

himself in his cell and at no point does he deny committing the crime, though

he does not necessarily tell all the truth.

I am sure the nay-sayers will ask what the point is of reading a crime

novel when the outcome – hanging – is unavoidable, just as the pedants

complained about The Day of the Jackal back in 1971 because General De Gaulle

was never actually assassinated and so we know the plot is not going to ‘work’.

His Bloody Project is

not a conventional crime novel, and certainly not a conventional ‘detective

story’ or ‘mystery’, but it is a novel, albeit a tricksy one, about crime. It

is also a very accomplished historical novel, describing in poignant detail the

hardships of a tiny crofting community in the western Highlands and ruthlessly

exposing the class divisions and social snobbery of the time (especially

against Gaelic speakers), as well as attitudes to the law, the press, the

strictness of the Scottish church and new-fangled theories of criminal

psychology. His Bloody Project is

not a conventional crime novel, and certainly not a conventional ‘detective

story’ or ‘mystery’, but it is a novel, albeit a tricksy one, about crime. It

is also a very accomplished historical novel, describing in poignant detail the

hardships of a tiny crofting community in the western Highlands and ruthlessly

exposing the class divisions and social snobbery of the time (especially

against Gaelic speakers), as well as attitudes to the law, the press, the

strictness of the Scottish church and new-fangled theories of criminal

psychology.

At the heart of the trial section of the book is the Catch-22 conundrum

that any sane person would naturally plead insanity in order to avoid the

hangman and mention is made of the famous M’Naghten Rules of 1843. {I was first

told about the M’Naghten Rules in a wine bar near Lincoln’s Inn by the divine

Sarah Caudwell, who claimed a family connection, though I could never work out

whether the connection was with M’Naghten or the judges trying his case, it

being a very convivial wine bar. Daniel M’Naghten was the first person found

not guilty of murder ‘by reason of insanity’ after his attempt to kill Prime Minister

Sir Robert Peel, although he did kill somebody else by mistake in the process.

Cynics, of course, would invert the Catch-22 to say he must have been sane to

want to shoot a politician.}

There is much to admire in His

Bloody Project not least the sheer quality of the writing and the

richness of the historical detail, which begs the question as to why the book

is not also in contention for the CWA’s Historical Dagger.

On a plot point, however, I do have one qualm. The protagonist, Roderick

Macrae, openly admits he did the triple murder though the identities of the

actual victims are cunningly withheld for a while and are quite shocking when finally

revealed. When the murders happen, they take place in a small, gloomy crofter’s

cottage and whilst the carnage is happening, an old woman – one of the victims’

mother – is sitting in an armchair in the shadows. Although she is spared by

the killer (Spoiler Alert: Roderick), she is not only never questioned as the

only witness by the authorities investigating the murders but is never

mentioned again in the book.

Such loose plot ends might, of course, be

part of the novel’s intellectual backbone and tricksiness and would not be

expected in a more conventional crime novel. So is it a crime novel or a novel

about crime or does it matter? It has received rave reviews from Jake Kerridge

(Telegraph) and Barry Forshaw (Financial Times), which is good enough for me,

and clearly the Booker judges have taken to it as I have, though as I am not

considered competent to judge the Flower and Produce Show my opinion is of

little worth.

The experience of my belated discovery of one unknown Scottish crime

writer published by a small Glasgow publisher has, however, prompted me to be

more aware of new (to me) Scottish crime writers from unknown (to me) Glasgow

publishers; so here’s another one.

Alan Murray was born in Edinburgh but has live for many years in Japan,

New Zealand and now Australia. His new novel, from Freight Books, is the World

War II conspiracy thriller The Turncoat which is set around the

German blitz on Clydebank, the industrial heart of Glasgow in 1941 and the

investigation by Military Intelligence officers rooting out the Nazi

sympathisers thought to be directing the aerial assault from the ground.

If you know your WWII history, given the location and the year, you will

not be surprised if Rudolf Hess puts in an appearance. And he does.

Saints & Sinners

I

have admitted many times that for some reason Leslie Charteris’ stories of ‘The

Saint’ completely passed me by in my youth, by which time Charteris had given

up writing full-length novels and was producing collections of long

short-stories and novellas. These stories were ideal for adaptation in a

television series, which many were and for me, my introduction to Simon Templar

was via Sir Roger Moore. I never became a member of The Saint Club, which was

started in 1936 and still going [see http://saint.org/stclub.htm ],

though I am assured it has absolutely no connection to the gay nightclub of the

same name which flourished in Manhattan in the 1980s. I do know several people, however, both crime

writers and civilians, who swear by the early ‘Saint’ books and even though I

had the privilege of meeting Leslie Charteris shortly before his death in 1993,

I never got around to reading one until two years ago when I was asked to write

an Introduction to new editions here and in the USA of The Saint in Europe.

Despite qualms about the overblown literary style and the political

incorrectness of that 1954 collection, I rather enjoyed those stories and

realised that Simon Templar formed the literary bridge between Buchan’s Sir

Richard Hannay and Fleming’s James Bond.

I have now – finally – got around to

reading a full-length Saint novel, The Saint Plays With Fire which was

originally titled Prelude For War when first published in 1938.

The original title and date are both significant for the novel is

virtually a personal declaration of war by The Saint on fascism in the form of

arms dealers working with a thinly-disguised

British Union of Fascists (‘British Nazis’) and Action Française (‘Sons of France’), and The Saint – and Charteris

– leave no doubt where their sympathies lies.

It is an enjoyable ripping yarn, starting with The Saint poking his nose

in where it is not wanted at a mysterious fire at a country house. There are

missing documents, an incriminating photograph, two murders, several car

chases, a kidnapping or two, a brush with Chief Inspector Teal as usual, and a

very impressive and totally mercenary femme

fatale in the form of the aristocratic Lady Valerie Woodchester, who might

not actually be the airhead she at first seems to be. There is also a

supporting role for The Saint’s idiotic, often unintelligible side-kick Hoppy

Uniatz and other ‘regulars’ from the early days.

But – and the ‘but’ was inevitable – there are passages of narration

which are hard to digest and they seem to get worse in the second half of the

book; an indication perhaps that Charteris was happier in the shorter forms of

fiction he was to adopt after 1947.

Take for example, this rather superfluous paragraph which tells us that

Mr Teal is chewing gum:

“He

had got his spearmint nicely in into condition now – a plastic nugget,

malleable and yet resistant, still flavorous, crisp without being crumbly,

glutinous without adhesion, obedient to the capricious patterning of his mobile

tongue working in conjunction with the clockwork reciprocation of his teeth,

polymorphous, ductile.”

None of which adds much, if anything, to the plot or the character of

Chief Inspector Claude Eustace Teal.

Or this passage, where The Saint suggests to Teal that another

character, Fairweather, may be the guilty party:

“And

a great grandiose galumptious grin spread itself like Elysian honey over Simon

Templar’s eternal soul. The tables were turned completely. Fairweather was in

the full centre of Teal’s attention now – not himself…The moment contained all

the refined ingredients of immortality. It shone with an austere magnificence

that eclipsed every other consideration with its epic splendour. The Saint lay

back in a chair and gave himself up to the exquisite absorption of its

ambrosial glory.”

At times one

feels as if Charteris was reading a Thesaurus in a hurricane or trying to

out-do Michael Innes in full flight, though with Michael Innes there was

usually a point, or at least a punch-line, to such verbosity.

One final example, again from later on in the book, as we find The Saint

tied up and seemingly at the mercy of the bad guys and with one bound is

miraculously free:

“…as

he stood still no one was paying much attention to him. But in that volcanic

immobility his arms hardened like iron columns, strained across the fulcrum of

his back like twisted bars of tempered steel. The muscles writhed and swelled

over his back and shoulders, leapt up in knotted strands like leathery hawsers

from his shoulders down to his raw and bleeding wrists; a convulsion of

superhuman power swept over his torso like the shock of an earthquake. And the

ropes that held his hands together, weakened by the loss of the few strands

that he had been able to rub away in the few minutes that had been given him,

were not strong enough to stand against it. There was a snap as the fibres

parted; and his arms sprang apart with the jerk of unleashed tension, He was

free.”

All this happens so quickly that the guard – standing next to Templar – doesn’t even have time to draw his gun,

which probably proves that in 1938 not even the fascists could get decent

staff.

I did, however, enjoy the description of a hotel commissionaire resuming

“his thaumaturgical production of taxis.”

Now that’s one I

shall keep in mind for the next time I stay at The Savoy.

Chilling Stuff

Macmillan,

a publishing house famed for championing some of the most respected names in

British crime fiction (Colin Dexter, H.R.F. Keating, Peter James, P.M. Hubbard

and many more) seems to have acquired a taste for the spooky.

Out this month, and chilling in more ways than one, is The

Ice Lands, written, naturally enough by an Icelander, a well-known poet

there, Steiner Bragi. This is no ordinary piece of Nordic Noir (as it will

probably be classed) as four thirtysomething city types head off into the wild

hinterland of financial crisis-hit Iceland, presumably to discover something

about themselves (shades of Deliverance

perhaps). Of course they discover something pretty horrible in the icy fog

which descends and forces them to take shelter in an isolated farmhouse and for

a while the reader is convinced they are in Pincher

Martin territory. At one point I felt myself longing for a map of Iceland

so I could identify the terrain being described but I thought no, why bother;

I’d be far too scared to ever go there.

In January, Macmillan publishes the supernatural thriller Under

a Watchful Eye by horror writer Adam Nevill and though the setting

seems initially familiar and cosy – the coast of Devon – the story certainly doesn’t stay cosy for long.

To be honest, the novel I am really looking forward to from Macmillan in

January is The Death of Kings, which will be the new novel (set in 1949 I

believe) to feature police detective John Madden as created by South African

journalist Rennie Airth, who will then be entering his 82nd year.

I have been a fan of the John Madden books since his spectacular debut

in River

of Darkness in 1999, the hunt for a serial-killer in 1920s rural

England before anyone had thought up the term ‘serial killer’. Many thought it

was Airth’s fictional debut, but he had tried his hand at a couple of thrillers

before then, Snatch! – a comic crime story of a kidnapping gone wrong in

Italy – in 1968 and Once A Spy in

1981. After a gap of 18 years, he gave us Inspector John Madden and now, 18

more years on, we will have his fifth adventure.

|

|

A Pendulum Due

I know I will be showing my great age when I say that Adam Hamdy’s forthcoming thriller Pendulum, coming from Headline in November, reminds me of an early Robert Ludlum. It begins with unsuspecting photographer John Wallace held captive, bound and with a noose around his neck at the mercy of a crazed killer who brings along his own music soundtrack (‘Air’ by Rogue; ‘Polarized’ by Seven Lions – anyone?) to hang his victim to. Oh, and the killer has his own ‘superhero’ uniform.

Thanks to a happy structural fault, our hero gets free, falls from a high window and limps away into Maida Vale where he catches a double-decker bus in a scene which may be an homage to the film of The Ipcress File. From there the action moves to Paris and then New York where Wallace teams up with a rogue FBI agent and a conspiracy is revealed which is nothing less than the total destruction of FaceTube, YouBook and all those forms of ‘social media’ which seem so popular among the young people these days.

At this point, all my sympathies switched to the bad guy determined to teach interweb ‘trolls’ (as I believe they are called) a lesson.

The Stories Behind The Stories

There are remarkably few good biographies or autobiographies of thriller writers, unlike crime writers if I may be allowed to make the distinction (of course I’m allowed; it’s my bloody column). Agatha Christie is certainly well covered and there is a very decent biography of Dorothy L. Sayers by the late Barbara Reynolds and an excellent one of Margery Allingham by Julia Jones.

On the thriller front, Ian Fleming was well served by Andrew Lycett (though there have been many more ‘biographies’ of James Bond than his creator); Geoffrey Household wrote a quite brilliant memoir Against the Wind in 1958 and one wishes he’d done a second volume in the thirty more years before his death; and Eric Ambler wrote the mischievous (the clue is in the title) Here Lies Eric Ambler in 1985.

But last year we were treated to a memoir by Frederick Forsyth, The Outsider, and a superb biography John Le Carré by Adam Sisman.

And now, in from the cold cliffs of Cornwall (or should that be Cornwell?) comes the inside story from the old spymaster himself, The Pigeon Tunnel, published by Viking and sub-titled by John Le Carré ‘Stories from My Life’.

Some of the ‘stories’ have appeared elsewhere and will be well-known to Le Carré fans, although anyone wanting to know about the author’s life will surely have read The Naïve and Sentimental Lover, A Small Town in Germany and the brilliant A Perfect Spy all of which contained strong autobiographical themes.

That is not to take anything at all away from The Pigeon Tunnel which is exquisitely written, poignant, forensically well-observed and in parts genuinely exciting, as when Le Carré relates his meetings – or trying to get meetings – with Yasser Arafat and a new generation of Russian gangsters who make the old KGB look like social workers.

It is only to be expected that a fair number of famous names are dropped along the way but never (unlike this column) capriciously. Film directors Karel Reisz and Lindsay Anderson are in there, as is Alec Guinness of course. So too is Reginald Bosanquet in a short but important cameo which Le Carré introduces with ‘You have to be closer to my age, I suppose, to remember Reginald Bosanquet…’

Sadly I am, John, and I do, but thanks for all the memories.

Hot Off The Presses

The always innovative Maclehose Press, who will always be remembered for unleashing girls with dragon tattoos on an English-speaking world, is this month publishing Shadows and Sun, the new crime novel by Dominque Sylvain alongside a mass market paperback of her Dirty War.

Each of these thrillers are billed as ‘A Lola and Ingrid Investigation’ which might make them sound like cosy American mysteries, perhaps featuring a pair of professional quilters investigating something nasty in the Cabot Cove woodshed, but they are certainly not that. This investigative duo, an odd couple to be sure, are Lola Jost, a retired French police commissioner, and Ingrid Diesel, an American masseuse (and former Las Vegas showgirl). Their amateur investigations are far from cosy, taking them into the world of arms dealing, defence contract scandals and very savage murders.

Dominique Sylvain is a French journalist who turned to crime writing over twenty years ago and has, over that period, completely re-written two of her earlier novels which is something to be admired – and feared – by many a crime writer, this one included.

I have to say I was somewhat confused by the Prologue to Dirty Story which includes as a subtext the ancient Babylonian myth made famous by Somerset Maugham as the ‘Appointment in Samarra’ story, where a man meets the figure of Death in a Baghdad market place. In Dominique Sylvain’s version, the figure of Death is clearly a female and I have absolutely no problem with that, but the famous plot-twist and punchline to this perfect short story here is that Death has an appointment that night in Samarkand, rather than Samarra. As all my readers will know, Samarra is in modern-day Iraq whilst Samarkand is in Uzbekistan. Am I missing something significant here? It wouldn’t be the first time, though it is unlikely to keep any other reader of Sylvain’s neatly noirish thrillers awake at night.

*

The charming and erudite Linwood Barclay has a new novel out from Orion, The Twenty Three, which is the third part of the ‘Promise Falls’ trilogy, a trilogy which I am ashamed to say has passed me by. The town of Promise Falls, the setting for Broken Promise and Far From True, seems a pretty dangerous place to live or rather die, as the inhabitants seem to be dropping like flies from a mysterious illness in the opening of The Twenty Three.

It proves to be another problem to add to the case load of Detective Barry Duckworth and I wondered if Linwood had ever considered sending his fictional hero over to England to team up with Inspector Lewis of the Oxford constabulary. The methods Duckworth and Lewis used to fight crimewould surely be of interest to the die-hard cricket fan if no-one else, but I will not suggest this to Linwood. He knows what he’s doing.

*

It is a staggering 52 years since the historical adventure thriller When The Lion Feeds launched the career of Wilbur Smith. In theory, a red-in-tooth-and-claw African family saga set in the 19th century had more in common with the novels of Rider Haggard and the 1880s than in a 1964 when paperback sales were dominated by Ian Fleming, Alistair MacLean, Len Deighton, Gavin Lyall et al.

After a couple of James Patterson-style franchise experiments with co-writers, Wilbur Smith is now back on his happy hunting ground of Ancient Egypt with Pharaoh, now out from Harper Collins and his many fans in many countries (on a recent visit to Italy, having been identified as a writer of sorts, the one question I was repeatedly asked was did I know Wilbur Smith?) will be delighted to hear that another chapter in his famous Courtney family saga, War Cry, is expected in March next year.

*

If your taste runs to contemporary crime fiction set in exotic places, then you could do much worse than sample The Bone Ritual by Julian Lees, published this month by Constable.

The setting is Jakarta, which is still called Batavia in my School Atlas, and stars Inspektur (the Indonesian spelling) Ruud Pujasumarta in the first of what looks as if it could be an interesting series.

Coming To A Bookshop Near You

I have not seen Mark Mills for several years, although he is the author of historical thrillers such as The Information Officer (2009) and House of the Hanged (2011) which I greatly admired and quite confidently rank him alongside Alan Furst, Philip Kerr and John Lawton when it comes to writing about Europe on the eve of, or during, World War II.

I was bemoaning the fact that for five years I had not read anything by Mark at a Shots Magazine Board Meeting (we all gather around the cheese board), when I was told in no uncertain terms that he had a new novel coming out in November – and also, in even stronger terms, that it was my round.

I am afraid I know no more than that Mark’s new book, from Headline Review, is called Where Dead Men Meet, but I am looking forward to it.

I have been sorely tempted by rumours of Anthony Horowitz’s forthcoming Magpie Murders, published this month by Orion, in which – I am told – I may well recognise several characters. However, despite wheedling, begging, threatening letters and straightforward blackmail, I have been unable to catch even a glimpse of an advance proof copy.

Rescued From The Wild

I was delighted to receive this picture of an energetic young person who, having climbed to the summit of Scafell Pike, England’s highest peak, on a glorious English summer’s day, discovered a book there!

Forensic examination of the picture seems to show that the book so bravely rescued from the wild was Lights, Camera, Angel! Unless my eyes deceive me, that is, which they often have before now.

And Finally

Dame Agatha Christie may have some of her most famous titles immortalised, very attractively, on postage stamps now…

…but it is always nice to see one’s name in lights in Piccadilly Circus.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|