|

Party Season

It did not take a genius, thank goodness, to predict that

the bestseller lists at the end of September would be dominated by new titles

from Felix Francis and Martina Cole, but it was an added bonus to have both

titles launched at splendid parties which kicked off the Autumnal crime fiction

social season.

Felix Francis’ Pulse, from Simon & Schuster,

is, I believe, the first ‘Dick Francis novel’ (as Felix is proud to call it) to

have a female protagonist, a doctor, investigating medical skulduggery in and

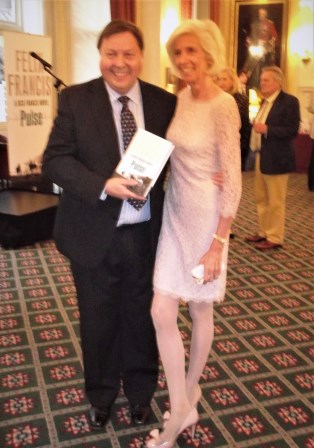

around Cheltenham race course. The new novel was launched at a party hosted by

Felix and Debbie Francis

which attracted a

distinguished audience of fans from the worlds of crime fiction and horse

racing, although both Shots editor Mike Stotter and myself were shocked as to

how Simon Brett had managed to get into the Cavalry and Guards Club without

wearing a tie…

The publication of Damaged marks a 25-year association

between Britain’s most successful living female crime writer and publisher

Headline and apart from seeing the welcome return of (retired) police detective

Kate Burrows, was given a terrific launch at a party in London’s West End where

Martina was positively mobbed by adoring fans.

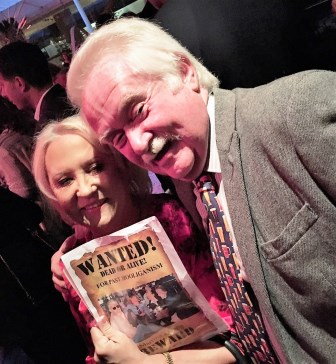

Unable to find a suitable card to mark the event, I

presented Martina with a crude, home-made one which commemorated a congregation

of hooligan crime writers, including Mark Timlin and Russell James, attending

one of the Crime Scene conventions at the BFI some eighteen years ago.

The launch of Damaged also gave me the opportunity

to meet and fall madly in love with Princess Muriel, long-suffering wife of

millionaire playboy and Shots benefactor Prince Ali Karim. It was a rare public

appearance for the Princess who, legend had it, is usually confined to the east

tower of the Karim palace. Fortunately, Prince Ali had moored his luxury yacht

at Canary Wharf in order to attend Martina’s party and the Princess was able to

slip away for a few hours.

On the Chase Case

Okay, so I may have been too quick to judge. And indeed, I

have admitted that on many occasions – as a late convert to Game of Thrones, sometimes about

publishers, very occasionally about agents – although never about Scandi-Noir

or Morris Dancing.

When it comes to crime writers, there are many who I

discover, now that great age if not wisdom has overtaken me, that I dismissed

rather callously in my youth as ‘not worth reading’ or, rather snobbishly, ‘not

to be seen reading’ and one of those was James Hadley Chase.

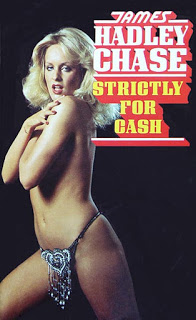

I was put off, in my youthful paperback-devouring days, by

the rather cheesy covers which adorned Chase’s books, most of which had snappy

pulp titles (famously Tony Hancock invented Lady,

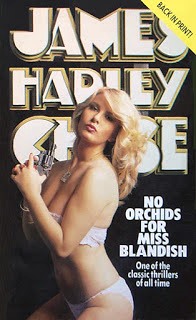

Don’t Fall Backwards but Chase really did write a book titled Kiss My Fist), although I had read No Orchids for Miss Blandish, his most

famous and notorious book.

James Hadley Chase (Rene Raymond Brabazon, 1906-1985) was a

prolific writer of faux American gangster novels famous for their cavalier attitude

to both women, cardboard characters and derivative plotting. The critic Julian

Symons described Chase’s output of more than 80 novels thus: “At worst the

writing is shoddy, at best like second-hand James M. Cain.”

Now I was never afraid to disagree with Julian Symons when

he was alive (so even less so now) and, on reflection, think that even

‘second-hand James M. Cain’ might be worth reading, but that’s not the point. I

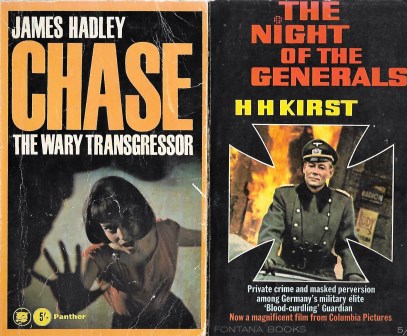

have discovered a Chase novel with the unlikely title of The Wary Transgressor which

not only provides an important historical footnote in the context of the

history of international thrillers, but is actually a damn fine crime novel.

Published in 1952, The Wary Transgressor is set in

northern Italy, mostly in Milan and Lake Maggiore, a few years after the end of

WWII. It has a plot which would have appealed to Hitchcock: a penniless

American drifter scrounging a living as a tour guide whilst working on a book

on religious art, meets and is seduced by an attractive woman who turns out to

be married to a rich Italian now confined to his Lake Maggiore villa following

a crippling car accident.

The drifter, David Chisholm, who has no papers and is

desperate to acquire a fake passport, allows himself to be sucked in to an

affair and, naturally, a plot to kill the disabled husband so that the ice-cold

‘widow’ can inherit. In many ways, it is a set-up worthy of Patricia Highsmith,

especially when it is revealed that this is no spur-of-the-moment crime of passion,

but that Chisholm has been specifically targeted because of his past – the very

reason he is on the run from the authorities.

This is revealed in what turned out to be a controversial

flashback (Chapter 6 in the book) to 1945 when Chisholm, then a US Army

sergeant, is assigned to show a US General around the art treasures – and flesh

pots – of Florence. The General turns out to be a psychopath, with obsessions

about cleanliness, who slaughters a local prostitute and puts Chisholm firmly

in the frame for the murder, but then gives him the chance to run.

Does any of this sound familiar? It reminded me immediately

of Hans Helmut Kirst’s Night of the Generals (published in

English in 1963) where the mad German General Tanz frames his driver in an

identical scene so wonderfully played in the film by Peter O’Toole and Tom

Courtenay.

Although I have owned a paperback of Kirst’s book for fifty

years, I had never noticed the acknowledgement at the end of the Author’s Note

that: In particular, the author wishes to

thank the English writer James Hadley Chase for making available important

source-material. Which suggests that the plagiarism of H.H. Kirst

(1914-1989), a respected German novelist, had been rumbled and presumably James

Hadley Chase was recompensed for the lifting of an entire chapter from The

Wary Transgressor published ten years earlier.

Ironically, Chase himself was to be successfully accused of

plagiarising a 1945 story by Raymond Chandler.

Worse Criminals

There are many distinguished writers who have turned away

from the dark side of crime and thriller fiction to the often darker side of

historical fiction. Both Ken Follett and Sarah Dunant cut their teeth on

contemporary crime fiction before taking the leap back in time to medieval

England and Renaissance Florence. C.S.

Forester penned at least one outstanding thriller and several ground-breaking

crime novels before Horatio Hornblower’s career took off; and even as he was

creating Sharpe thirty years ago, Bernard Cornwell was writing modern sea-going

thrillers, although the Napoleonic Wars and then the Dark Ages (and other

periods) subsequently claimed his creative juices.

And now my old chumette Minette Walters, who burst on to the

crime scene in 1992 with The Ice House, which one

distinguished critic described as ‘the most impressive first novel for years’,

has turned to historical fiction for, as she succinctly puts it: There are many worse criminals in history

than there are in crime fiction!

The setting for her new novel, The Last Hours, which is

published by Allen & Unwin next month is her adopted county of Dorset and

the year is 1348, when the Black Death came ashore there and spread ‘like black

smoke’ with frightening speed across the land.

The appeal of the subject is understandable – the biggest,

most frightening killer then known to man – especially to an award-winning

crime writer who happens to live at the epicentre of the pandemic (it really

did come ashore in Weymouth) but did wanting to write about it justify such a

drastic change in genres?

‘I wonder if it is such a big change?’ Minette tells

me. ‘The Black Death was the worst killer man has ever known. Which crime

author wouldn't want to write about it... and point fingers at the culprits?

There are many worse criminals in history than there are in crime fiction.’

Certainly, Minette’s ability to tell a suspenseful, page-turning story

(as she proved in classic crime novels such as The Sculptress, Acid Row and

Fox

Evil) is much in evidence in The Last Hours. Although the reader

knows what is happening, the characters – which include many strong female ones

– do not and how they react to the horror of the Black Death, and the speed

with which it spread, is key to the book. There is a particularly spooky scene

early on where a character realises what is happening by noting the growing

size of communal graves which have appeared overnight.

I hope The Last Hours will bring new readers for Minette as, although

distinctly different from her crime fiction output, it demonstrates that she is

still the fine story-teller which made her psychological thrillers so good. I

must also, however, declare an interest in the fact that the historical period

she is now working in (and a sequel is due in late 2018) has some significance

for me personally. For my obligatory mid-life crisis, I became an archaeologist

and the first skeleton I unearthed (every archaeologist wants to find a

‘skelly’), in Witham in Essex, was almost certainly a victim of the Black

Death.

The discovery enabled my publishers at the time to use the promotional

blurb: The crime writer who regularly

trips over real bodies.

|

|

Burning Bush?

Whenever I hear that yet another ‘Golden Age classic author’ has been ‘rediscovered’ and is to be republished, my usual reaction – apart from the obligatory “Who? No, me neither” is one of amazement that the well of forgotten masterpieces has not yet run dry.

But the latest candidate for revival, Christopher Bush, is certainly a name I know although as far as I can recall, I have only read one of his books.

Christopher Bush (1885-1973) had a prolific writing career which spanned the years 1926 to 1968, producing some 63 novels featuring wealthy gentleman sleuth Ludovic Travers (who has traits uncannily like Albert Campion), his man servant Palmer and Scotland Yard’s Superintendent George Wharton, as well as a dozen other books. The Case of the Tudor Queen (1938), which I have read, is workmanlike but very much of its time: a young woman is immediately thought of as acting suspiciously because she sets out ‘on a half mile walk without a hat’. If this type of sealed-in-aspic traditional detective story floats your boat, then you’ll probably appreciate the backlist of Christopher Bush. Christopher Bush (1885-1973) had a prolific writing career which spanned the years 1926 to 1968, producing some 63 novels featuring wealthy gentleman sleuth Ludovic Travers (who has traits uncannily like Albert Campion), his man servant Palmer and Scotland Yard’s Superintendent George Wharton, as well as a dozen other books. The Case of the Tudor Queen (1938), which I have read, is workmanlike but very much of its time: a young woman is immediately thought of as acting suspiciously because she sets out ‘on a half mile walk without a hat’. If this type of sealed-in-aspic traditional detective story floats your boat, then you’ll probably appreciate the backlist of Christopher Bush.

Reviewing Bush’s 1934 novel The Case of the Dead Shepherd for The Sunday Times, Dorothy L. Sayers said that whilst it was probably not as good as his previous title, ‘is thoroughly engrossing, well written and full of legitimate puzzlement.’ Shepherd for The Sunday Times, Dorothy L. Sayers said that whilst it was probably not as good as his previous title, ‘is thoroughly engrossing, well written and full of legitimate puzzlement.’

You’ll soon get the opportunity to judge for yourself as the ambitious Dean Street Press intends to reissue all 63 Ludovic Travers novels, the first tranche of ten titles appearing this month including a Christmas-set story Dancing Death from 1931.

London, East of Java

One of Hollywood’s crassest mistakes was to insist that its 1969 adventure movie Krakatoa: East of Java was geographically accurate. Only after many years and multiple consultations of school Atlases was it accepted that Mount Krakatoa is actually west of Java and the name of the movie changed by deed poll to Volcano.

I do not think publisher HQ will have the same problem on their hands with East of Hounslow, the debut novel of Khurrum Rahman which is published next month.

Billed as the first in a series to feature Jay Qasim, a feckless dope dealer in West London who lives with his Mum, has invested all his ill-gotten profits in a new BMW and rarely been outside Hounslow, who is approached by the security services to infiltrate a group of jihadists with who he has an unexpected connection.

East of Hounslow, for all its topicality, lacks the impact of Jeremy Cameron’s tales of dispossessed feral youths in Walthamstow which appeared twenty years ago and what could have been an interesting study of a British Muslim’s reaction to radical Islam is diluted by the fact that the protagonist, who seems to have lead a sheltered life, is portrayed as naively innocent despite being a drug-dealer. The book comes with a ringing endorsement from Ben Aaronovich (sic), who himself has London-based book out now.

The Furthest Station, published by Gollancz, is a novella set on the far reaches of the Metropolitan Line, out towards Chesham and Amersham, which I am pretty sure are west of Hounslow. Not that that matters in the slightest, for in Ben Aaronovitch’s world all bets are off and we are in the land of ghosts, ghoulies and things going bumpety-bump in the night.

A short, sharp treat for those who like their London underworld spooky and a Harry Potterish/Terry Pratchett take on life in the capital, which, given the popularity of A.K. Benedict and Christopher Fowler, is rapidly becoming a recognisable sub-genre of modern crime fiction.

Irish Noir

A new crime fiction festival, Noireland (see what they did there?), is launched this month in Belfast, running from the 27th to the 29th, featuring some notable names in the mystery world, and not just Irish ones.

Speakers will include Benjamin Black, Adrian McKinty, Abir Mukherjee, Stella Duffy, Louise Welsh, Brian McGiloway, Stuart Neville, Steve Cavanagh, Sophie Hannah and, from the USA, Robert Crais.

The convention takes place at the Europa Hotel Belfast and further details can be found at https://www.noireland.com/.

Bloodier Scotland

After what I hear was a very successful Bloody Scotland festival at Stirling last month, the Tartan Noir army is on the march again next month with much-anticipated titles; one a debut crime novel and the other a futuristic twist on the genre from an established master.

From Orion comes Shadow Man by debutant Margaret Kirk, although ‘debutant’ may be a misnomer as Margaret was the winner of the 2016 Good Housekeeping Novel Competition.

Shadow Man comes highly praised by Val McDermid (“a harrowing and horrific game of consequences”) and is set in Inverness where police detective Lukas Mahler (a detective with, naturally, a past) is faced with two murders. One is the killing of a daytime TV star and the other the murder of a ‘CHIS’ – a Covert Human Intelligence Source, or, as they used to be known, a police informer.

Chris Brookmyre (the writer formerly known as Christopher) has been one of the leading Scottish crime writers for twenty years now, but of late has moved towards science fiction and the ‘techno-thriller’.

His new novel, Places in the Darkness is published by Orbit, the sci-fi and fantasy arm of Little, Brown and Brookmyre firmly sets his story in outer space when a murder takes place on Cuidad de Cielo (CdC) a huge orbiting space station which had, until now, been regarded as a city without a crime.

A murder in space is surely the ultimate way of providing a closed-circle of suspects and has certainly been experimented with by crime writers in the past. I am reminded of Reginald Hill’s 1990 novella One Small Step which tasked an ageing Dalziel and Pascoe with a murder investigation on the Moon in 2010!

Like Chris Brookmyre, the late Reg Hill had a fondness for science fiction and wrote it under the pen-name Dick Morland; and like Reginald Hill, Chris Brookmyre seems incapable of writing an uninteresting book.

Not To Be Confused

I doubt if anyone will really confuse Chris Petit’s forthcoming Pale Horse Riding with Stephen Hunter’s outstanding 2002 thriller Pale Horse Coming, even though both feature horrific scenes in prison camps and the very appropriate motif of Death riding into town on a pale horse.

Whilst Hunter’s Pale Horse Coming is a brilliant shoot-’em-up adventure set in a cruel backwater Mississippi penal colony in 1951 and not only takes the form of a classic Western but actually utilises characters and tropes from westerns of the silent movies of Hollywood, Chris Petit’s new novel takes a more sombre tone with its setting in the most notorious prison ever – Auschwitz.

Published next month by Simon & Schuster, Pale Horse Riding sends Chris Petit’s German detective duo of Schlegel and Morgen under (very flimsy) cover in to Auschwitz in 1943 to investigate corruption and stolen gold being smuggled out through the postal system. (The gold in question having already been stolen from the mouths of its murdered owners.)

The gradual revelation of the true horror of Auschwitz shocks even the hard-bitten, war-damaged pair of Schlegel and Morgen, who appeared – and barely survived – in The Butchers of Berlin which, for legal reasons, I am unfamiliar with. I will, however, now seek it out, as Chris Petit, always a thoughtful writer, has produced a nightmarish vision of a slice of Hell on Earth.

The ever-inventive MacLehose Press are turning to modern Germany in January 2018 for a new series of crime novels which will, hopefully, mount a decent challenge to the all-conquering Scandi-noir movement (for which MacLehose could be said to be partly responsible.)

Set among the chocolate-box scenery of the Black Forest and featuring a middle-age divorcee police inspector called Louise Boni, Zen and the Art of Murder by award-winning author Oliver Bottini (four times winner of the German Krimi prize), is the first in the series, with two more titles planned for later next year.

The title refers to Boni’s investigation of a Japanese monk wandering the snowy countryside near Freiburg and should not, of course, be confused with other well-known crime titles written by H.R.F. Keating and James Melville.

Nor indeed with the excellent crime novels written by the late Michael Dibdin featuring his enigmatic Italian detective Aurelio Zen.

Notes and Corrections

I am indebted, as I usually am, to Lizzie Hayes-Sirrett of Mystery People who has pointed out that the Peter Cheyney novel, Dressed To Kill, which I referred to last month was in fact first published as Night Club in 1945.

The original was, I feel, the far better title and had the better cover.

Coming Up

I know that Christmas Lists are already being compiled by many a book-lover (it’s never too early to gauge whether you’ve been naughty or nice) and I have no doubt that on many early lists will be titles by two prolific and rightly popular crime writers.

Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express needs no introduction, but HarperCollins have produced a sumptuous new hardback edition to coincide with the release of the new film version directed by, and starring, Kenneth Branagh. And the tireless Michael Connelly (does this man never sleep?) has another novel out, mere months after the last one, from Orion: Two Kinds of Truth. A new Michael Connelly is usually good news; the fact that this is a Harry Bosch story makes it excellent news.

As always, I will be taking a short break from crime fiction over Christmas and turning to non-fiction and thanks to those kind people at Allen & Unwin I already have one of my wish list: Scorched Earth by Sue Rosen, a social history of how Australia coped with the threat of a Japanese invasion during WW2.

Sue Rosen’s book tells a story which is neither well-known or appreciated in this country and it is a story packed with suspense, fear, espionage and jeopardy. So perhaps it’s not that much of a break from crime fiction after all.

Toodles!

The Ripster

|