|

Taking Stock

Having

had some time on my hands recently, I have taken it upon myself to do the

annual stock-take of the output of Shots

eZine (as I am told I must call it). The results impressed even me.

During

calendar year 2017, Shots carried

reviews of 270 new crime novels (more than 20 new titles a month); 26 features

and 13 interviews on and with authors; and some 256 blog posts carrying news

from publishers, authors and the world of crime fiction in general, as well as

hosting ‘blogtours’ by guest authors.

Indeed,

this very column, Getting Away With

Murder, mentioned some 240 books (mostly new ones, and all in print

somewhere) and an equal number of crime-writers, many of them still alive.

Taking

stock of my own situation and boosted by the large number of messages of

support (many from people to whom I do not owe money) following my recent heart

surgery (a heart … who knew?), I have decided to try and continue this column

although it may appear somewhat irregularly. If you would like to receive a

notification of when a new column is posted (and do not receive one already),

please email shotseditor@yahoo.co.uk

and put GAWM in the subject box.

A

Gauntlet Thrown?

Press Releases which accompany proof

copies of forthcoming books are often the source of genuine nuggets of

information among the hyperbole. Their main function of course is to promote a

particular book and an individual author but many of the claims made in the

average press release fall into publicity cliché territory. For example, all authors are ‘bestselling’ and all

debut authors are ‘an exciting new voice in crime fiction’.

In the release which accompanies the

advance proofs of The Smiling Man to be published by Doubleday in March, there is

however a claim I have not come across before when describing the author – the

disgracefully young Joseph Knobbs writing as Joseph Knox – who happens to be

Waterstones ‘Crime Buyer’ which I presume means the buyer of crime fiction

rather than the book store’s purchaser of criminal services and hirer of

hit-men. Joseph’s day job, says the release, makes him ‘possibly the best-connected and best-read crime author out there’.

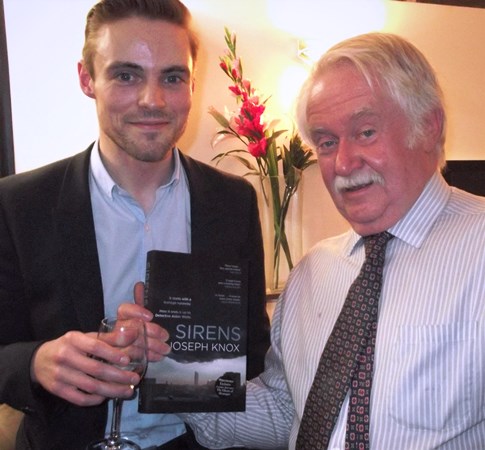

It was not a boast he made himself, at

least not when I met him last year on publication of his debut novel Sirens,

which I am sure went on to be a best seller.

Buying crime fiction for a chain as

large as Waterstones would, I guess, make him well-connected, at least among

publishers, but best-read crime author?

Sounds to me rather like a challenge. Surely that is a claim which could only

be justified by an exhaustive pub quiz…

If there was an award for the most blurbed author by other authors (which

I’m sure there will be one day), then a strong candidate must be C.J. Carver

with her new thriller Know Me Now which is published as a

paperback original (?)this month by Zaffre although I believe an eBook version

appeared some time ago. (I am afraid I have been left far behind by modern

publishing methods.)

Know Me Now is, I think, the third novel to feature

her ex-MI5 agent hero Dan Forrester teaming up with DC Lucy Davies, and comes

with quotable recommendations from: Lee Child, Harlan Coben, Mason Cross, Simon

Kernick, Mick Herron, Meg Gardiner, Michael Jecks, Ruth Downie, Jack Grimwood,

Parker Bilal, Julia Crouch, Tom Harper, Natasha Cooper, Isabelle Grey and Maxim

Jakubowski, which is quite an impressive fan club.

Adding

Lustre to the Golden Age

If you ever wondered where the Colin

Watson-inspired village of Mayhem Parva was situated, I would suggest it is

just down the road from the village of Nasely, the home, and favoured setting,

of Golden Age crime novelist Agnes Crabbe. No, me neither; but then I was

unaware of the rural hotbed of homicide which is Nasely before I read Stevyn

Colgan’s A Murder To Die For just out from publisher Unbound.

To say that Agnes Crabbe (1895-1943)

was unappreciated in her day is an understatement as the novels she wrote

featuring her lady detective Millicent Cutter were not, due to a bequest of the

author, published until 2000. This did not, of course, stop them from being

adapted for television and popular enough to inspire a ‘murder mystery festival’

in the village of Nasely where most attendees of any sex dress in suitable

‘Golden Age’ style as fictional detective Millicent Cutter in between

refreshments at the Moore Tea, Vicar?

café.

Not surprisingly, real life (or should

that be death?) murders take place during the murder mystery festival and,

frankly, we would have been disappointed if they hadn’t. The jokes come thick

and fast, from the outrageous – a character called Stingray Troy Phones Maria

Savidge has, unsurprisingly, anger-management issues (as well as a brother

called Thunderbirds Jeff Scott John Virgil Alan Parker) – to the sly, with a

few digs at Agatha Christie, some wonderful observations on the fans who attend

murder mystery festivals, often in character, and the jealousies of rival

‘appreciation’ organisations. In fact, fan clubs and literary societies don’t

come out of this book at all well and by the end one fears for the reputation

of Ngaio Marsh and her devoted readership, although Margery Allingham, thank

goodness, seems to survive unscathed.

A Murder To Die For is a gentle spoof on the classic

English village murder mystery which is, unusually for traditional mysteries,

underpinned by believable police work probably due to the author having been a

police officer for many years and the son of a long-serving homicide detective.

That may be where the police procedure comes from, but Steve Colgan is also a

writer on the television show QI and

Radio 4’s The Museum of Curiosity, which

explains (and recommends) the sense of humour on display.

A

Most Dangerous Game

I have noted before now the growing

number of female thriller writers (action thrillers rather than crime novels)

and how many prefer to be known by initials, such as ‘C.J.’ or ‘L.A.’, rather

than their full forenames. Another one forms one half of ‘R.J. Bailey’, the

husband-and-wife writing team (aka Mr and Mrs Rob Ryan) behind Nobody

Gets Hurt, which is published by Simon & Schuster this month.

It may be a thriller which is

half-written by a female, but the protagonist is wholly female, this being the

second outing for Sam (Samantha) Wylde, ex-British army now retrained as a

bodyguard, or Personal Protection Officer, and security consultant, currently

on assignment at the Monaco Grand Prix.

Whilst searching for a missing daughter

and an ex-husband (possibly dead), Sam Wylde needs all her considerable

military skills and resourcefulness in a plot which encompasses gun-running to

the IRA and a tense, hair-raising journey across France and into Spain which

reminded me of Gavin Lyall in his heyday. And I can’t say fairer than that.

Getting

Carter

My mention last month of Nick Triplow’s

biography of Ted Lewis Getting Carter (No Exit Press) sparked

a positive avalanche of emails from old fans of the author of Jack’s

Return Home, famously filmed as Get

Carter, as well as potential new fans previously unaware of the work of

this pioneer of ‘Brit noir’.

Whether Lewis is in danger of being

forgotten in his home country, the emails I have received suggest that he has

certainly not been in America, Italy and Australia and I predict he will be

remembered in Bristol in May, when biographer Nick Triplow appears at this

year’s Crimefest convention.

Last month I suggested that Ted Lewis

had been ‘air-brushed’ out of some of the key guides to crime writing, but I

must credit two which included Lewis, albeit briefly.

The book Crime Writers, edited by

Harry Keating and published by the BBC in 1978 to accompany the six-part

television series of the same name, certainly mentions Ted Lewis – and Jack

Carter – in the same breath as Lee Marvin in Point Blank and the novels of Donald Westlake. (According to Nick

Triplow, Lee Marvin was an iconic figure and inspiration for Ted Lewis.)

The 1998 anthology The Big Book of Noir published

in America by Carroll & Graf, contains an essay on ‘British Neo-Noir’ which

acknowledges Lewis’ place in the history of British crime writing. It was

jointly written by a pair of young(ish) enthusiasts called Maxim Jakubowski and

Mike Ripley. I wonder what ever happened to them?

|

|

Ben’s Return Home

I cannot recall ever having read a crime novel set on the Scilly Isles before, but I have now and it’s a very good one. Hell Bay by Kate Rhodes, published by Simon & Schuster, takes place on Bryher, the smallest inhabited Scilly island – one and a half miles long and half-a-mile wide with a population of 72 permanent residents, not counting the 26 who leave the island each winter for paid employment on the mainland.

As you can see, we already have the makings of a classic, traditional English murder mystery (and of course there is a murder) - a closed circle of suspects physically contained on a small island no-one can leave as a storm has disrupted the ferries to nearby Tresco. Whilst a murderer may be kept on the island that also means that the usual forces of law and order cannot get there so it is fortunate that London policeman DI Ben Kitto is on hand and even more fortunate that Kitto was born and raised on Bryher, even if his homecoming does turn out to be something of a busman’s holiday.

Hell Bay is a finely-paced traditionally British murder mystery with a cast of believable, well-drawn characters and a setting which cunningly contrasts the panoramic Atlantic vistas and seascapes with the introspection of a small, isolated community. And before you ask, there really is a Hell Bay on Bryher (and Hell Bay Hotel). It was also the title of the 1984 historical novel by Sam Llewellyn.

Perhaps best known for his seafaring thrillers and his ‘follow-ups’ to Alistair MacLean’s Force 10 (from Navarone) war stories and to Erskine Childers’ Riddle of the Sands, Sam Llewellyn is well versed in the history, geography and waters around the Scilly Isles, particularly Tresco, as he was born there.

Lost in Translation

Some years ago, at one literary festival or another, I attended a seminar chaired by that erudite and award-winning crime writer Peter Guttridge. The topic was crime fiction in translation and Peter’s guests for the evening were four foreign crime writers being published in the UK for the first time and their translators. I was particularly keen to ask two questions of the assembled panel. Firstly: of the writers hoping to break into the British market, which British crime writers had they read and enjoyed? Two said ‘Sherlock Holmes’, one said ‘Raymond Chandler’ and the fourth couldn’t think of one at all.

Determined to get my money’s worth (I had indeed paid for a ticket), my second question went to the translators, all British, asking which crime novels/thrillers they a had read recently. Three of the four translators couldn’t bring one to mind and the fourth, who translated from the Spanish, named a (very good) crime novel by Cuban-American Alex Abella but admitted he’d only read it in the hope of getting the job of translating it.

The reason I mention this is because translators have upset me yet again. As my knowledge of modern languages is slim (there are disappointingly few crime novels written in Latin, Greek or Old Norse these days), I cannot criticise the grammatical or linguistic accuracy of the translator’s work but when it comes to crime novels and thrillers, I can, and certainly do, take umbrage at their lack of feeling for the genre.

This becomes obvious in their inability to translate humour, especially black humour, which I admit is difficult, and in their inability to understand firearms and ballistics.

As a case in point, I cite the award-winning German crime novel Zen and the Art of Murder which is published in English this month by MacLehose Press. Early on in the book, one German policeman lends his gun to an unarmed female colleague:

Hollerer passed her his gun. It was S.I.G. SAUER (sic), not a Walther PS. Having checked the safety catch, she stuck the revolver into her waistband.

Normally written as Sig Sauer, the Swish-German firearms company is noted for some famous products and supplying them to most European law enforcement agencies, but not, as far as I know, revolvers. They tended to specialise in automatic pistols, as below:

I mention this particular bugbear of mine as it reminds me of many years in a previous life trying to persuade lazy journalists not to refer to ‘beer and lager’; lager, along with ale, porter, stout and, oddly, barley wine, all being types of beer.

The translator’s confusion (I shall put it no stronger than that) between automatic pistols and revolvers can have serious consequences. In one well-known Italian crime novel by the Naples writer Maurizio di Giovanni, the serial killer being hunted by the police uses an automatic pistol and at one point leaves a vital clue – an ejected cartridge case – at a crime scene. This does not deter the translator from describing the killer’s gun as a revolver. Perhaps he just liked the look of the word. Clearly, he was not bothered about accuracy, continuity, police procedure or the plot.

Legends Revisited

The Hard Case Crime imprint of Titan Books has been responsible for reissuing many fine titles of vintage American crime fiction and introducing some interesting writers to new readerships, among them James M. Cain, Gregory Mcdonald and Samuel Fuller, as well as encouraging new talent (!) such as Ed McBain, Gore Vidal and Stephen King.

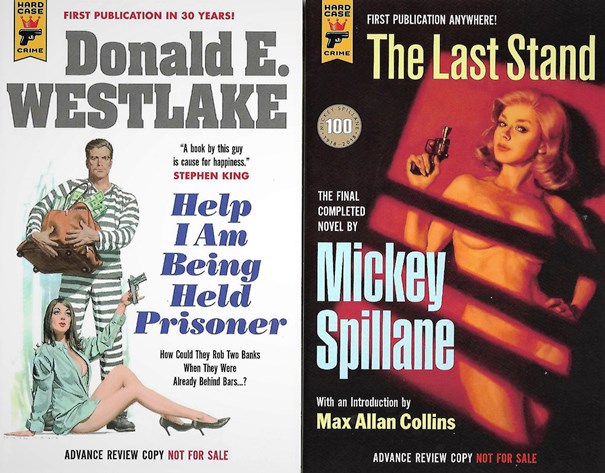

Hard Case see in 2018 with the news of titles by two legends of American crime writing and for once I do not use the term ‘legend’ loosely: Donald Westlake and Mickey Spillane.

Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008) was a highly prolific, multi award-winning mystery writer better known to hard-boiled fans as Richard Stark, one of around twelve pen-names he used in his career. Apart from noir classics, writing under Stark name, such as The Hunter (filmed as Point Blank), Westlake had a considerable reputation for comedy crime and ‘caper’ novels.

Hard Case are highlighting this lighter side of Westlake with the reissue of his 1974 romp Help I Am Being Held Prisoner, which they will publish in February.

In March, to mark the centenary of his birth, Hard Case will publish The Last Stand, the last completed work by Mickey Spillane, which comes with the reissue of an early novel (more a novella really) A Bullet For Satisfaction edited by Spillane ‘completist’ Max Allan Collins.

There was a time when Mickey Spillane was one of the best-known names in crime writing in the world, his violent, sexy (and sexist) thrillers featuring heroes such as Mike Hammer and Tiger Mann, causing outrage among reviewers (Julian Symons called his work ‘distasteful’) but selling by the million.

Spillane’s heyday, in terms of productivity and sales, was the Fifties and, in this country at least, his star began to wane in the Sixties as the more salacious end of popular fiction was cornered by Harold Robbins and the violence portrayed on the cinema screen (and on the nightly news from Vietnam) outdid even the tough, revenge-fuelled activities of Mike Hammer. At one time, Spillane’s name was international short-hand for hard-boiled crime stories, but all his novels, I believe, went out of print here during his lifetime – although many are now available again. His name too diminished in terms of recognition. Twenty years ago, in a previous life, I worked with a man called Michael Spillane who had been born in the mid-Sixties, which would have made him 30-something.

He had absolutely no idea why work colleagues of an older generation, such as myself, insisted on calling him Mickey and not Michael or Mike, which he preferred. Even when we explained that we were referencing the author of I, The Jury and Kiss Me Deadly, he was no wiser.

Christmas Treat

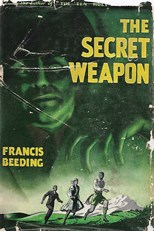

I have had a restful Christmas (thanks for asking) mostly on doctors’ orders but have managed to indulge myself in one way in that I have finally acquired a book I have been stalking on the jolly old interweb for several years. Thanks to the generosity of two Americans who live almost a continent apart, award-winning mystery writer Margaret Maron and veteran reviewer and collector Marv Lachman, I received an early Christmas present in the shape of The Secret Weapon by Francis Beeding, which was originally published in the UK as Not A Bad Show in 1940.

As well as being a fan of Beeding’s rip-roaring thrillers (which sold in huge numbers in the 1930s), I am currently researching how British thriller writers responded to the outbreak of WWII as opposed to detective-story writers of the so-called ‘Golden Age’, many of whom didn’t seem to notice there was a war on. Not A Bad Show, which opens on 1st September 1939, was clearly vital to my researches but copies are very hard to find, so I was delighted when my colonial chums came up with a 1944 American edition and generously covered the outrageous charges now being levied by the US Postal Service.

I will no doubt be reporting progress on the paper I am preparing in the coming months, and I hope fans of Eric Ambler, Geoffrey Household, Dennis Wheatley, Hammond Innes, Leslie Charteris and Nevil Shute (among others) will not feel short-changed. In the meantime, I am enjoying The Secret Weapon if only for the fact that at one point the hero, who has left America to come to Europe to fight the Nazis, takes umbrage at the phrase “You’ve not done half badly” because he had lived for years in a country where the deliberate use of meiosis is unknown.

Any thriller, let alone one written in the darkest days of WWII, which can slip in the word meiosis - as well as numerous quotes from Shakespeare and Chaucer - has to be admired.

A Happy New Year to One and All.

(I’m just happy to be here).

The Ripster.

|