|

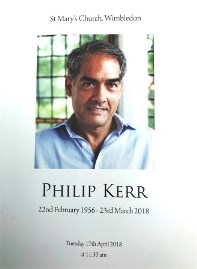

Cruel April

April is the cruellest month – the opening of Eliot’s The Waste Land (Part 1: Burial of the

Dead) – seems sadly very apt this year as it saw the funeral of Philip Kerr and

a memorial service for Colin Dexter, who died last year.

I

met Philip and Colin at roughly the same time in 1990 on the fringes of

Bouchercon XXI in London, the first Bouchercon crime convention to be held

outside the USA and possibly the only one ever held at a venue without a bar.

Over

the years I have had the great pleasure in reviewing the novels of both, for

the Daily Telegraph and the Birmingham Post, and have the

distinction of being reviewed by both Philip and Colin. In Time Out, Philip reviewed my 1991 novel Angels in Arms, opening

with a description it took me some time to live down: ‘Physically, Mike Ripley resembles the Irish police captain who always

gets it wrong. But his writing is faultless, and the funniest thing about

Ripley is his novels…Comic crime writing isn’t easy, but Ripley’s Angel novels

are as witty as they are deftly plotted.’

And

in 2005, Colin was asked to review my historical thriller Boudica and the Lost Roman

for the Birmingham Post, graciously

noting the jokes (even more graciously ignoring the mistakes in my Latin) and

judging that the novel showed ‘insight,

compassion and considerable scholarship’. (After that appeared I asked the editor of the

paper if I could have the hand-written review Colin had submitted as a

souvenir. I was told it had been ‘recycled’.)

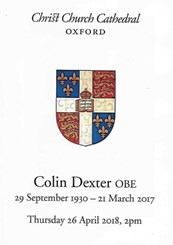

Colin’s

Memorial Service, held in Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, was an inspiring

event, with eulogies from Philip Pullman, Kevin (‘Lewis’) Whately, Val

McDermid, members of the A.E. Houseman Society and numerous crossword experts.

I rather dauntingly found myself in the choir pews sitting next to the

crossword editor of The Times, but

relaxed at the civic reception which followed the service in the company of,

among others, Inspector Morse producer

Ted Childs, crime writer Michael Jecks and Hilary Hale, Colin’s editor back in

1990 who introduced the two of us, therefore bearing an awesome responsibility…

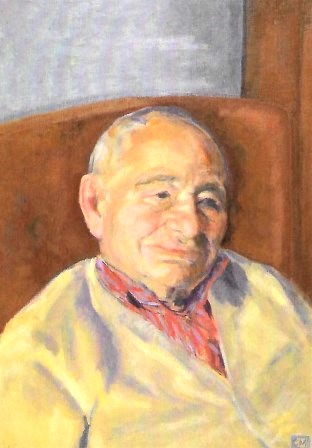

Looking

down on us as we remembered him, was Colin’s portrait by artist Celia Montague,

which I had not seen before. I also learned that during his National Service in

the army’s Signal Corps in 1948-49, Colin became a high-speed Morse operator.

Books of the Month

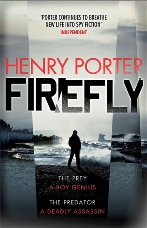

I

am tempted to use the old reviewer’s cliché that a plot has been ‘ripped from

the headlines’ when recommending Firefly by Henry Porter, published

this month by Quercus.

Technically,

I suppose, the news cycle has moved on to the recent horrific chemical attacks

in Syria, but the sad, underlying story of Syrian refugees fleeing into Europe

should never be allowed to drop off the news agenda. It is actually within this

chaotic stream of refugees flooding from Turkey to Greece, Macedonia and

Serbia, that Henry Porter sets his story. A young, intelligent Syrian boy

carrying a phone on which there is damning evidence of ISIS atrocities, sets

off in advance of his family to try and reach the safety of Germany, ducking

and diving along the way to dodge the perils which face him at every stage of

his journey. Not only does he have to avoid people smugglers, thieves, child

molesters and border police but he might just have an ISIS terrorist cell

hunting him. Help, if they can find each other in the Balkan mountains, is on

hand in the shape of Luc Samson, a freelance intelligence agent with a personal

refugee past and an unusual second occupation as a successful gambler on

horse-racing.

The

boy’s desperate journey and the people he meets along the way, coupled with

Sampson’s hunt for him using every play in the modern spy’s training manual,

make for a total enthralling story told with pace and compassion.

As

something of a squeamish soul who normally avoids crime novels which feature

vulnerable children and pregnant women, I was unsure how I would react to Snap,

the new novel published by Bantam, from

the award-winning Belinda Bauer, as it contains a family of three of the former

and two of the latter; one whose murder is the prologue of the book and the other

who is in jeopardy from the start.

Told

initially as parallel narratives seemingly unconnected, the two streams

converge into a gripping narrative thanks to Bauer’s clear, unfussy prose and a

sharply observant eye. This is superior British noir (only in Britain would the police screw up a stake-out in such

a way) in a domestic setting and is a thriller worthy of sharing a title used

back in 1974, when Belinda Bauer was still at school, for another suspenseful

slice of domestic crime and punishment.

Yes,

that Jaqueline Wilson whose early

published work included four excellent psychological thrillers before she

switched to children’s fiction. I wonder how she got on after turning her back

on crime fiction…

With

an Andrew Taylor historical mystery, the reader is guaranteed good history,

good mystery and very good writing. The Fire Court, from HarperCollins,

delivers on all fronts with a multi-threaded plot centred on the Fire Court

established after the 1666 Great Fire to adjudicate on re-building rights in a

London parts of which resemble, thanks to some brilliant writing, a cross

between the Blitz and downtown Aleppo.

In

a devastated city, the rebuilding contracts could be a rich prize, though who

would have thought town planning and civic governance might be corrupt? To keep

an eye on proceedings (or at least try to), Taylor employs James Marwood, as do

several interested parties, and who suffers a violent disfigurement in the

process. Another character from Taylor’s best-selling The Ashes of London is

the enigmatic ‘Cat’ - an intelligent woman who realises her dream of becoming

an architect will never be fulfilled because she is (a) the daughter of a

regicide and (b) female.

There

is a satisfyingly gruesome murder by fire bomb and a running motif of the

casual violence meted out to women and servants in a world dominated by strong

beliefs in heaven, hell and redemption mixed with guilty feelings about having

killed one king and restored another. Andrew Taylor conjures that world

brilliantly, though in the process makes one very grateful for the twin modern

blessings of sanitation and antibiotics.

The

Fire Court stands

alone but for maximum enjoyment I strongly recommend reading The Ashes

of London first.

Alex

Reeve has set the bar high for his entry into crime fiction, for not only is

his chosen setting a Victorian one – London of 1880 – which has been regularly

visited by crime writers since Conan Doyle fired the starting gun, but he has

as his protagonist a young man who is actually a young woman, trapped in the

wrong body. In The House on Half Moon Street, from Raven Books, life for

chess-playing mortuary attendant Leo (who was born Charlotte) gets even more

complicated when the love of his life Maria, a working girl in the brothel of

the title, is found dead and Leo is initially the prime suspect – at least

according to the fearsome Detective Sergeant Ripley (who surely deserves a

spin-off series). The physical problems of being a woman masquerading as a man,

especially when visiting a brothel or when incarcerated in an all-male prison

cell with only a crude shared toilet are not glossed over. In fact, there may

be too much detail for the more sensitive reader and there is the problem that

Leo, with so much to hide and being sweetly innocent on so many things, is not

convincingly equipped for the role of detective he adopts although he seems to

have unlimited funds when it comes to hiring cabs. Still, Alex Reeve

confidently sets a cracking narrative pace and maintains it as his hero/heroine

comes up against the brick wall of Victorian social privilege.

{

If

you ever wanted to know anything – and by ‘anything’ I mean everything – about Agatha Christie’s

work in the theatre, then Agatha Christie A Life in the Theatre

by Julius Green is as good as a ticket in the front stalls. Now a superbly

illustrated paper from HarperCollins, which shows just how far paperback

production values have come, Green’s surely definitive work will answer any

question and (Spoiler Alert!) might just provide some questions for a certain

quiz at this month’s Crimefest.

Forbidden Books of the Month

For

legal reasons I can tell you nothing about the new James Bond novel Forever

and a Day by Anthony Horowitz, which I am really looking forward to

having thoroughly enjoyed his previous outing in the Bond continuation

franchise, Trigger Mortis.

All

I can say is that the book is due to be published on 31st May and

will be, I am told, the fortieth official James Bond novel.

I

know even less about John Lawton’s latest novel Friends and Traitors

despite being a long-time fan of John’s historical spy thrillers featuring the

Troy dynasty and just about every real shady political figure in the 20th

century.

I

am reliably informed that the book was published last month and has even been

reviewed in Shots though it has been

studiously kept off my radar. It looks like I will have to buy a bloody copy at

Crimefest, where John is one of the

most eagerly anticipated speakers.

One

new book I am not allowed to mention because of a strict embargo until

publication on 22nd May, is Stephen King’s The Outsider from Hodder

and Stoughton.

As I always do what I am told by publishers, I will

say no more other than to hazard a guess as to what will be the #1 bestseller

on 23rd May.

Nordic Lightly Noir

To

coincide with is new novel Holy Ceremony from Bitter Lemon,

Finnish crime writer Harri Nykänen attempts to convince us that Finland can

offer the reader the lighter side of Nordic Noir.

In

an essay on the Crime Reads website (http://crimereads.com/finland-the-lighter-side-of-nordic-noir/) the creator of Ariel Kafka, one of

the few (if not only) Jewish policemen in Helsinki, does his best to soften the

stereotypical view of his fellow Finns, though perhaps not in a way of which

the Finnish Tourist Board (I am sure there must be one) would approve.

For

example, Harri claims that when it comes to suicide rates, Finland aims to be

the ‘top nation worldwide, easily beating all of Scandinavia’ and takes a wry

pride in the old legend that his country spawned ‘the unholy trinity of hard

liquor, a knife and a Finn’.

Nordic Lightly Noir

To

coincide with is new novel Holy Ceremony from Bitter Lemon,

Finnish crime writer Harri Nykänen attempts to convince us that Finland can

offer the reader the lighter side of Nordic Noir.

In an essay on the Crime Reads website (http://crimereads.com/finland-the-lighter-side-of-nordic-noir/) the creator of Ariel Kafka, one of the few (if not only) Jewish policemen in Helsinki, does his best to soften the stereotypical view of his fellow Finns, though perhaps not in a way of which the Finnish Tourist Board (I am sure there must be one) would approve.

For example, Harri claims that when it comes to suicide rates, Finland aims to be the ‘top nation worldwide, easily beating all of Scandinavia’ and takes a wry pride in the old legend that his country spawned ‘the unholy trinity of hard liquor, a knife and a Finn’.

|

|

Live Now, Read Later

When

I was young and innocent and prone to wandering through forest glades and

fields of daffodils reciting those immortal lines Hello trees, Hello flowers, I remember being warned not to read a

rather risqué novel Live Now Pay Later by Jack Trevor Story.

I

was never sure why I was warned against the book – presumably it promoted ‘fast

living’ – and I actually did manage to avoid reading it although there was a

time when its Penguin film tie-in edition seemed to be absolutely everywhere in

the Swinging Sixties.

I

had no idea until recently that Jack Trevor Story (1917-1991) had also tried

his hand at genre fiction with Westerns and thrillers in the long-running

‘Sexton Blake’ series, which I also managed to avoid with consummate ease just as

I have all the hundreds(?) of other ‘Sexton Blake’ stories.

Clearly

created in a wave of Sherlockian mania, London private detective Sexton Blake

made his first fictional appearance in 1893 and went on to appear in comic

strips, magazine serials, novels and even a television series into the1970s. It

has been estimated that in total, there have been 176 ‘Blake’ authors. Many of

the stories were churned out by stables of agency writers often sharing the

same ‘house’ pen names – or perhaps it was one writer or editor using a lot of

pen-names. Such things were far from unknown in the history of British pulp

paperbacks, nor was the recycling of plots or even entire novels, republished

with a different title or different hero in the hope not even the most

dedicated Sexton Blake fan would notice. (This recycling of previously

published novels was known in the trade as ‘de-Blake-ing’.)

One

of the stalwarts behind the Sexton Blake ‘industry’ was journalist turned

author turned editor and eventually publisher, W. Howard Baker (1925-1991) who

licensed the Sexton Blake brand when it was dropped by the magazine company

Fleetway Publications in 1963. Baker revived the Sexton Blake Library where

readers could receive 24 books by post ‘to any address in the world’ for an

annual subscription of 96/- (ninety-six shillings or £4.80, as was).

This

‘Fifth Series’ of the library included The Company of Bandits (1965) by

Jack Trevor Story, four titles by ‘W.A. Ballinger’ and one by ‘Peter Saxon’

(both pen-names of Howard Baker) and two by W. Howard Baker himself, including Every

Man An Enemy.

Published in 1966, Every Man An Enemy is a

‘revised and enlarged’ edition of Baker’s novel Walk in Fear from 1957, and

to be honest, is far more interesting and funnier, when it doesn’t feature

private detective (should that be ‘consulting detective’?) Sexton Blake who

eventually makes an appearance half-way through. The plot involves the

manuscript of a potential best-selling novel delivered anonymously to a seedy

agent wonderfully described as ‘a parasitic growth on the publishing world’ and

‘a literary spiv’ who operates out of an office above a Chinese laundry on the

Tottenham Court Road.

The agent immediately sells the book to

an eccentric publisher (a mad ex-Spitfire ace) and then realises he doesn’t

know who the anonymous author, pen-name MacDonald Hall, is or how to find him –

or her (spoiler alert!). To help get his grubby paws on the sizeable advance

offered, or at least his agent’s percentage, the agent gets help from a wily

Fleet Street journalist – another wonderfully seedy character – and finally

Sexton Blake, aided briefly by his side-kick Tinker and hardly at all by his

pet bloodhound Pedro.

When five ‘authors’ turn up all

claiming to be MacDonald Hall, the action hots up and the plot thins visibly

when the murders start to happen, so naturally all concerned gather at the

publisher’s country mansion for Christmas (as you do) and things are sorted out

at rather a frantic pace.

Blasts from the Past

There

should probably be a special place in the history of British thrillerdom for

Kenneth Royce’s 1970 novel The XYY Man. Not only was it Royce’s

best-known book (he wrote some 40 novels) and was acclaimed by Dame Ngaio Marsh,

no less, as ‘a brilliantly sustained thriller’, it was turned into a very

popular television series, and not one, but two, spin-off series; all the time

being based on a totally spurious premise.

The

anti-hero of The XYY Man is Spider Scott, a professional cat burglar so good

at his job that British Intelligence is happy to sub-contract some very

dangerous, not to say illegal, tasks to him. Why ex-con ‘Spider’ is such a good

recruit for anything dodgy is because he is blessed, or cursed, with an extra

male ‘Y’ chromosome; hence ‘XYY’. This genetic bonus pre-disposes the carrier

to a life of anti-social behaviour and crime, which was indeed a popular theory

in the late 1960s despite the fact that there was absolutely no scientific

backing for it.

The

first two Spider Scott thrillers, from 1970 and 1971, are now reissued as Top

Notch Thrillers by Ostara Publishing (www.ostarapublishing.co.uk) as trade paperbacks and eBooks,

reviving the ‘XYY Man’ after being out-of-print for more than 20 years.

Supposedly

based on a real cat burglar whom he met whilst a prison visitor, Kenneth Royce

(1920-1997) turned ‘Spider’ Scott into one of the most popular anti-heroes on

television in 1976. Yet it was Spider’s nemesis in the novels, the dubious

Detective Sergeant Alf Bulman, who was, ironically, to have the longer career

on the small screen, appearing as a character in the 1978 series Strangers and then in his own spin-off

series (as a private eye) in Bulman in

1985.

I’ve Never Seen Star Wars

Well

of course that’s ridiculous; I’ve seen all the Star Wars movies. Indeed, in 1977 before the film was released

here, I was involved in a feature for BBC Look East explaining, with the help

of the Physics Department of Essex University, how lasers could be used as

weapons in space, illustrated by bits of the trailer from the forthcoming film.

But

I must admit I never saw The Wire, even

though I was well aware of it and was a great fan of David Simon’s Homicide, both the book and the

television series. However, I can now fill in a crucial gap in my knowledge by

reading All the Pieces Matter a lively, very readable oral history of

the series by Jonathan Abrams, out later this month from No Exit Press.

When The Wire was

first broadcast, I had legitimate medical reasons for not watching it. Abrams’

book makes me wish I had. Oh, if only there were some way of electronically

recording television programmes for later viewing, or some facility for

‘catching up’ on programmes missed… I am sure the technology is not beyond the

wit of man, although it can be confusing to those of us who are elderly and

infirm. For example, I have only just realised that ITV2+1 is not actually ITV

3.

But

then I am so old I remember having to get up from one’s seat, walk across a room

and turn a knob in order to change channels (as fantastical as that sounds

now). Fortunately, here at Ripster Hall, there are under-butlers employed

solely to carry out that task.

Mapping Spenser

My

first encounter with Robert B. Parker’s smart-talking Boston private eye the

monomynous Spenser was in 1982 when, as a subscriber to the Keyhole Crime

imprint, I obtained Looking For Rachel Wallace.

Keyhole

was a book club of sorts (run, I think, by Mills & Boon) where one bought

four paperbacks a month at reduced price. As one didn’t get a choice in which

four titles came through the post each month, many of the Keyhole paperbacks

came as a surprise. Some of them, a pleasant surprise as it was via Keyhole

that I discovered writers such as Simon Brett, Margaret Miller and Robert

Barnard.

Robert

B. Parker was a particular gem and I hastily tracked down other Spenser titles,

in those days published by Penguin. I remember being quite distraught when

Penguin, for some reason, dropped Parker and then delighted when I heard that

No Exit Press had picked up his back list. Today, No Exit still keep faith with

Spenser by publishing the novels by ‘continuation author’ Ace Atkins.

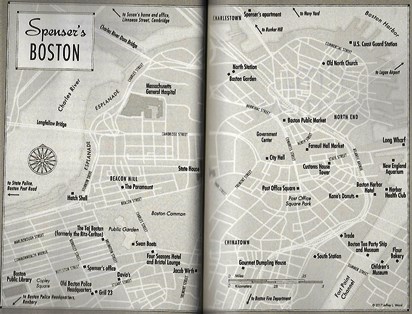

The

latest, possibly the 46th if my arithmetic holds up, Little White Lies, is out

now and comes, as all good detective novels used to, with a map – of Spenser’s

native Boston, of course.

All Our Yesterdays

Inspired

by the television programme which looked back over world events twenty-five

years earlier (and which was last broadcast twenty-nine years ago) I have been

rootling through my archives to see what I was reviewing for that once-great

newspaper the Daily Telegraph in the

Spring of 1993.

The

pick of my ‘Crime Guide’ was Hard Aground by that ‘poet of the

hardboiled’ (and he is a poet) James Hall. At the time, James Hall’s

Florida-based crime novels were some of the most eagerly-anticipated fiction

from the other side of the Atlantic. Hall, an academic whose students included

Dennis Lehane, has sadly dropped off the radar, at least in the UK and I

believe his latest thrillers have yet to find a British publisher.

‘Crime’

and ‘Florida’ immediately suggest Carl Hiaasen and by 1993 he was established

enough for his backlist to be raided for early works not previously published

here. Written in partnership with fellow journalist William Montalbano, Powder

Burn and Trap Line appeared as paperbacks and while they might not have

enhanced, they certainly did not diminish the reputation of Hiaasen as the king

of comedy crime.

Another

of my American picks was In A Pig’s Eye by Robert Campbell,

‘an unusual, fresh, observant and intelligent’ look at streetwise crime and Democratic

party politics in Chicago. But then I was always a fan of Robert Campbell

(1927-2000) who, back in 1975, as R. Wright Campbell had written the stunning

WWI thriller The Spy Who Sat and Waited now, sadly, something of a forgotten

masterpiece of both historical crime and spy fiction.

Flying

the flag for the home nations, and certainly holding their own against a wave

of classy American invaders, were Mark Timlin with Falls the Shadow, the

eighth of his Sarf London Nick Sharman thrillers; Philip Loraine (aka Robin

Estridge, 1920-2002) with Crackpot; Lesley Grant-Adamson with

her elegant Euro-thriller The Dangerous Edge; and a very

impressive debut, Night’s Black Agents, by David Armstrong, who was later to

write the wry and acerbic ‘self-help’ books How

Not To Write A Novel.

It

was an interesting and satisfying start to the crime fiction scene of 1993,

with not a Nordic, nor a Domestic, Noir in sight.

Straying from the Straight and Narrow

When

I stray from the path of crime fiction as I occasionally do, it is usually into

the world of non-fiction, and invariably into the fields of history and

archaeology. I have, however, been tempted out of my comfort zone by Posing

for Picasso by Sam Stone (Word Fire Press).

Sam

Stone is an established author of fantasy and horror fiction (and I crave her

indulgence if my terminology is incorrect) but in Posing for Picasso she

has produced an intriguing ‘mash up’ - as

I believe the young people call it - of

horror, the supernatural and the detective novel with more than a fair

sprinkling of art appreciation thrown in for good measure, creating a very

spooky cocktail indeed.

But

do not take just my word for it. The book comes with advance praise from Paul

Finch (the noted crime and horror writer), Ken Bruen (that consummate authority

on Celtic noir) and best-selling crime writer Peter James.

One reason to get Carter

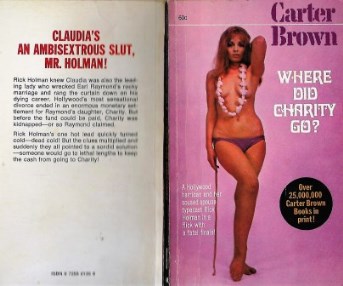

My

mention of the prolific Australian pulpster Carter Brown has resulted in

several confessions from male readers of a certain age that they only bought

Carter Brown books ‘for their covers’. I have no idea why Where Did Charity Go? of

one of his Rick Holman, Hollywood private eye, novels from 1970 would have been

popular.

Unless,

of course, it was due to the flamboyant cover copy which announces, on the

back, that Claudia’s An Ambisextrous

Slut, Mr Holman! And on the front: A Hollywood harridan and her soused spouse

typecast Rick Holman in a flick with a fatal finale!

Who

could possibly resist blurbage as colourful as that?

See

You at Crimefest,

(not

if I see you first),

The

Ripster.

|