Pearl Anniversaries Are A Nuisance

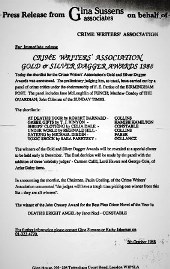

I received a salutary reminder that I

have been involved in crime writing for thirty years when I discovered this

press release in a Cambridge archive.

It announces the shortlist for the first

annual dagger awards I attended as a member of the Crime Writers’ Association

in 1988. Naturally, as an unknown non-entity (I am now a known unknown) I was

not on it, but the names listed bring back fond memories. Of the short-listed

authors, I subsequently got to meet Sara Paretsky – and become a member of Sisters in Crime – and not only met, but

became good friends with Robert Barnard, Tim Binyon, Reginald Hill and Michael

Dibdin (none of whom are still with us) and Janet Neel, now Baroness Cohen of Pimlico,

who won the John Creasey Award. All in all, a very impressive short list.

Even among the judges, I got to know

(and be generously reviewed by) John Coleman, fellow East Anglian Matthew Coadey

(sic) and F.E. ‘Bill’ Pardoe, whom I eventually replaced as reviewer for the Birmingham Post.

Actually, my first novel, Just

Another Angel, was published thirty years ago this month and launched on an unsuspecting world on the opening

night of the famous Murder One bookshop, then on Denmark Street. It therefore

seems the ideal time to announce that my latest novel will cash-in mercilessly

on my pearl anniversary.

Mr Campion’s War will be published by Severn House on

31st August and is my fifth ‘continuation’ novel to feature Margery

Allingham’s famous detective in his golden years. In fact much of the book is a

flashback to Albert Campion’s exploits working for British Intelligence during

WWII and I suppose is my first full-length attempt at a spy story. I say that

with some trepidation as the nub of the plot was given to me over lunch by none

other than Len Deighton, who would undoubtedly have made a better job of it

than I.

Whilst obviously proud that a new book

(my 26th) will mark my thirtieth year in this murky business, I am

still at a loss as to what the appropriate commemorative present might be for a

pearl anniversary. Diamond tie-pins are popular, so I am told, as are gold

rings and silver brooches, but what goes with pearl? I am advised that I should

on no account Google the word ‘necklace’ in this context, though I have no idea

why.

They Don’t Write ’Em Like That Anymore

Although I don’t think I have actually

said it, I am often quoted as saying ‘They don’t write thrillers like they used

to.’ Well of course they don’t and in many ways that’s a very good thing, but

I’ve just read one which certainly reminds me of the heyday of the British

adventure thriller back in the 1960s. (As chronicled in that admirable textbook

Kiss

Kiss Bang Bang published last year.)

The Break Line, by journalist and documentary

film-maker James Brabazon and published by Penguin/Michael Joseph, certainly

celebrates many of the tropes of those vintage action-packed thrillers (being

written by a journalist is one of them) and although the hardware and weaponry has

been updated, and in great detail, we have a cynical tough-guy hero (an

Anglo-Irish army-trained assassin), an exotic location – the jungles of Sierra

Leone – a mad scientist concocting a world-threatening plague (of sorts) aided

by a touch of voodoo and, of course, treachery in high places.

The action is pretty much not stop and

the hero, Max McLean is put through hell, shot, drugged, tortured (in a

particularly eye-watering scene), trapped underground and chased by ‘Sleepers’

– a fearsome enemy who do everything but

sleep (unless shot in the head) and the body count is huge. There is even a violent

finale at the famous Fitzroy Tavern on

Charlotte Street in London’s Fitzrovia, and goodness knows we’ve all had one of

those.

Given the rather fantastical

developments of the plot The Break Line reminds me of the

work of John Blackburn (1923-1993) who was the master of genuinely spooky

thrillers combining thriller elements with espionage, threads of science

fiction and, as in one of his most famous titles, blood-curdling Gothic horror.

John Blackburn’s thrillers are sadly

little remembered these days, although Valancourt Books (http://www.valancourtbooks.com/) of Richmond, Virginia have done an

absolutely first-rate job of keeping many of his titles in print.

James Brabazon has probably never heard

of John Blackburn – he wasn’t born when Blackburn was turning out his best work

– so he will just have to take it from me that on the strength of this debut

novel, he is worthy of following in Blackburn’s bloody footprints.

And if you thought they didn’t write

World War II escape stories like they used to, well they do.

In my youth, the paperbacks which sold

in huge quantities were often non-fiction rather than fiction and drew on true

stories from the war, invariably featuring plucky British soldiers or airmen

often escaping from prisoner-of-war camps. The

Colditz Story, The Wooden Horse and

The Great Escape were titles

well-known to every schoolboy, as were the films made from them and anyone

unfamiliar with those films will miss many of the jokes in Ardman’s Wallace and

Gromit adventures.

Now The Hidden Army by Matt

Richards and Matthew Langthorne, published by John Blake, tells the story of a

plan thought up by Airey Neave of MI9 to hide ‘downed’ or escaped airmen

(British and American) in a forest camp south of Paris – next to a German

ammunition dump – until the liberating Allied armies could reach them after

D-Day. It’s a fascinating story and a fitting one to be told in the centenary

year of the RAF, although it does not underplay the fantastic bravery of the

French and Belgian resistance fighters and civilians who helped in the plan.

In a way it is also a tribute to Airey

Neave, one of the few men to escape from Colditz, who became an MP and was

assassinated by a car bomb planted by the Irish National Liberation Army in

1979 as he drove out of the House of Commons underground car park.

Top-Notching

From the days when they really did

write them like that, courtesy of Top Notch Thrillers, come this month’s most

notable revivals.

Published within three months of the

death of Ian Fleming in 1964, The Man Who Sold Death introduced as

hero John Craig, an immediate candidate as a replacement for James Bond.

Whether his creator, James Munro, ever thought that is not known, but this book

and three further ones were successful, particularly in America. Under his real

name James Mitchell abandoned Craig for a new creation in many ways the

antidote to James Bond but almost as iconic: David Callan, the hero of the

legendary television series, several novels and numerous short stories.

Craig, like Callan, fought his way up

from the ranks, ending WWII as a decorated naval officer who then went into the

shipping business, making a fortune by ‘shipping’ arms and ammunition around

the hotspots of the Mediterranean, plenty of shady friends and even more

dangerous enemies who eventually take their revenge on Craig and his fellow

smugglers. To survive, Craig calls on a previously acquired skill set (crack

pistol shot, judo black belt) and takes the war to his enemies with the help of

the highly secret Department K who were looking for a new assassin and Craig

seems to fit the bill.

Less well-known in British thriller

history is the mononymous private detective Raven, as created by James

Quartermain in The Diamond Hook in 1970, a thriller which takes a long and

very hard look at the effect of the heroin trade as it blighted the twilight of

the Swinging Sixties. The novel starts in Swinging London, with a key scene in

a disco called Voices Off where the ear-splitting soundtrack is provided by a

modern beat combo called The Doors.

Things turn very dark as Raven is

force-fed (injected) heroin until he is an addict (shades of the film French Connection II to come in 1975),

but even thus handicapped he pursues the villains to the Dordogne and an

explosive (literally) climax.

If Raven and James Quartermain have

slipped from memory, the man behind the pen-name, James Broom-Lynne (1916-1995)

certainly left his mark on thriller fiction of the Sixties in his successful

‘other’ career as an artist and illustrator. He was the man responsible for

many a successful dust-jacket, including designs for Dick Francis’ racing

thrillers and Adam Diment’s The Dolly Dolly Spy.

For further information on Top Notch

Thrillers, consult: https://bit.ly/2uLNrP0

Berlin Games

Can there be a more popular city setting for a spy thriller than Berlin? Even when the name of the city does not appear in the title - The Quiller Memorandum was originally The Berlin Memorandum and the Little Bear of David Brierley’s superb post-war thriller is Berlin (the Big Bear is Stalin) - there is no doubt that Berlin is the star.

Now dedicated fans of the spy story and the city are unleashing their combined enthusiasms to produce a podcast in the always entertaining Spybrary series from Berlin itself ( http://spybrary.com/deighton-day/) using as an excuse, not that one is needed, a celebration of Len Deighton’s 1983 novel Berlin Game, the first book in his epic triple trilogy featuring Bernard Samson.

The Berlin podcast, available later this month, will be recorded in many of the locations used in the book, with Shane Whaley (the Mr Big of Spybrary) and Rob Mallows (the Red Grant who guards the wonderful Deighton Dossier website) and, fittingly, the starting point for their expedition will be Checkpoint Charlie.

Things have, of course, changed since the heyday of Checkpoint Charlie’s Cold War notoriety and one has to wonder what Bernard Samson, Harry Palmer, Alec Leamas, Colonel Stok, Quiller, Johnnie Vulkan and a host of others would have made of the rather prominent McDonalds now entrenched nearby.

It is not that Berlin needs a boost to its image when it comes to thriller settings. It seems to be doing very well currently, as can be seen in Jack Grimwood’s Nightfall Berlin now out from Michael Joseph/Penguin, which revisits the Cold War days of 1986, and in Michael Russell’s The City of Lies, which recently appeared in paperback from Constable and which begins in Dublin in 1940 but rapidly moves to…you know where.