|

The

Lunchtime Thriller Club

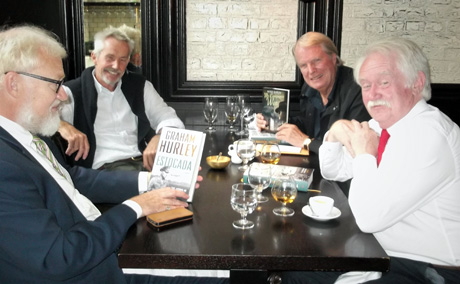

Canadian bookman, reviewer and

awesomely well-read thriller fan Steele Curry was in London last month hosting

his legendary lunch for favourite thriller writers, and once again I managed to

infiltrate proceedings.

This year’s gathering was in

honour of crime-writer-turned-historical-thriller writer Graham Hurley and Paul

Mendelson, the author of many books on card games and the playing of them –

particularly bridge and poker – who has now turned to the Dark Side and written

a series of thrillers set in South Africa. For legal reasons I have yet to

discover Paul Mendelson’s fiction (though Steele Curry rates it highly) but

even before he turned to excellent historical thrillers, I was a fan of Graham

Hurley’s Portsmouth based ‘Faraday and Winter’ novels, which have now been

transposed to Le Harve and turned into a hit French TV series under the title Two Cops on the Docks.

I have been rather dilatory in

reviewing Graham Hurley’s new thriller Estocada, published by Head of Zeus

in June, which is the latest novel in his ‘Wars Within Wars’ series.

Set in 1937 and 1938 in the run-up to the Munich crisis and the Nazi expansion

into Czechoslovakia and the possibility of a second world war, Estocada

follows the lives of two men – one a young German Luftwaffe pilot already battle-hardened in the Spanish civil war

and the other a Scot, a former Royal Marine, who is recruited as a reluctant

spy by British Intelligence. Both men have romantic entanglements which do not

end well, and both become aware of the coming conflict yet are powerless to prevent

it. Although main characters in Hurley’s clever and sympathetic narrative, they

are very minor players in history, but they are the conscience and humanity of

the story.

The novel contains cameo

appearances by real historical figures who could have altered history, but

either would not or could not, notably Goering, Ribbentrop, Chamberlain and

Churchill. There is also a rather disturbing scene where Heinrich Himmler

conducts an interview with Hurley’s German hero whilst taking a bath and there

are astute observations on Hitler himself, both as demonic orator and as an

unimpressive, somewhat impatient passenger on his private aeroplane (about

which I will say no more for fear of giving away a plot spoiler).

Estocada – which is Spanish for the

killing thrust of a matador’s sword in the bull ring and also a metaphor for

the Luftwaffe’s spanking new Messerschmitt fighter – is a finely written

historical thriller set in a period which continues to attract some outstanding

writers such as Philip Kerr, Ben Pastor, John Lawton, David Downing, Robert

Harris and Luke McCallin. Graham Hurley, already a well-established crime

writer, is not out place in such company.

Picking

at a Gothic Seam

I always believe everything

publishers tell me for, by ancient oath and secret ritual, publishers are sworn

always to tell the truth. Of late, however, they have been rather economical

with the accuracy where publication dates are concerned. At least seven new

novels in the second-half of this year have had their release dates altered;

some advanced, some delayed.

Working from advanced proofs, where the date of publication is clearly

printed, I have already reviewed a novel six weeks before it was available and

publication of Ian Rankin’s new novel (see on) has been advanced by two weeks.

Another early arrival, which

almost caught me out, is The Corset by Laura Purcell which

was, according to the advance proof, scheduled for an October publication.

Fortunately a diligent publicist for publisher Raven Books took the trouble to

contact reviewers and warn us that publication had been advanced to September.

The Corset is the tale of two women

trapped in the crushing constraints of Victorian society, represented by the

corset of the title, an analogy which even I understood. The dual narrative is

very deftly handled and the world it conjures is pure Jekyll and Hyde, a place

where horrors lurk beneath the façade of prosperous respectability. (I am

guessing that the period is the 1850s, though I may be wrong).

Dorothea is an heiress visiting

prisoners as an act of charity and also to find evidence to support her belief

in the pseudo-science of phrenology. Meanwhile Ruth, awaiting trial for a

murder she has confessed to, recounts a life story of desperate brutality and

poverty, her guilt woven around a belief that her skill as a seamstress has

supernatural powers to kill or cure. So far, so Gothic; but as the gallows

loom, fantasy gives way to cruel and twisted truths cogently described both

forensically and psychologically.

This is literate, intelligent

and gripping stuff but in some places not for the faint-hearted. Male readers

especially will require the smelling salts at the ‘difficult birth’ scene.

Supreme

Scandi

The regular reader of this

column fully appreciates my undying respect for ‘Nordic Noir’ or Scandinavian

crime fiction….as long as it is written by Michael Ridpath, the English crime

writer who has ventured beyond the Northern Lights with a series of excellent

thrillers set in Iceland starring police detective Magnus Jonson.

The Wanderer, published this month by

Corvus, is a very welcome new addition to the series and involves Magnus in a

murder where the prime suspects are almost certainly part of a film crew making

a documentary on the legendary Viking explorer Gudrid the Wanderer.

Now any book which starts with

a discussion of a thirteenth-century ‘Vinland Map’ (okay, so the Nordics did

discover America) between three characters who ‘were only on their third bottle

of wine’ before dinner, certainly sparks my interest. Goodness knows, we’ve all

had evenings like that…

As usual, Ridpath nails his

Icelandic setting, even giving a good explanation of what Skyr (the go-to Icelandic breakfast) is, as well as interesting,

rounded characters and throws in a fascinating historical sub-plot, a visit to

the Vatican’s secret archives and a nicely bitter taste of academic rivalries.

Spoiler

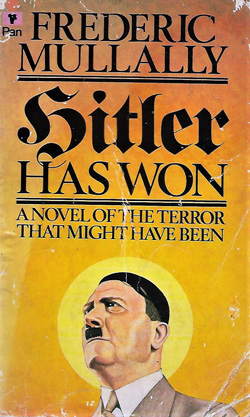

Alert: Hitler wins!

Just when you think you must

have read every ‘alternative history’ thriller where the Nazis won WWII,

another one turns up. Not that’s it a new one. Hitler Has Won by

Frederic Mullally (1918-2014) was first published in 1975; it’s just taken me

over forty years to discover it.

It is quite an unusual example

of the sub-genre, with very few fictional characters, and tries to present a

global political scenario (Mullally was a political journalist at one point),

which makes it read more like an alternative history than a thriller, if that

makes sense. The timeframe is 1942 to 1944 and the set up is, as the title suggests,

that Hitler has, basically, won.

As the novel begins, German

armies have reached Moscow (and bulldozed the Kremlin), the British have been

pushed out of North Africa and Pearl Harbour hasn’t happened (yet). Now with

time on his hands, Adolf decides to get down to writing his next bestseller, Mein Seig, with the help of a one-armed

young veteran who, up until now, has been a dedicated follower of most things

Nazi. He, of course, begins to see things clearly, but Adolf – now the master

of Europe – is revealed as totally bonkers (who knew?) and has his eye on the

only possible next job after Führer:

Pope!

I have to admit that I’ve

probably read more Nazi-based thrillers than I should have involving Hitler’s

brain, Hitler’s children, Hitler’s clones, Hitler’s hidden treasure etc., but

his moving into the Vatican was a new one on me.

Goody

bag?

As a follower of, and

occasional fellow passenger, crime fiction over the years, I have received a

weird variety of ‘promotional items’ accompanying new books. These have

included: a traveller’s sewing kit, chocolates, a torch, key-fobs,

flash-drives, bookmarks galore and miniature bottles of vodka and bourbon sadly

too small to qualify as a decent bribe.

But until now I have never

received what we used to call on aeroplanes, a sick-bag! An unused one, I hasten to add, and personalised to

promote a collection of stories designed to make those frightened of flying

even more scared: Flight or Fright edited by Stephen King and Bev Vincent and

published this month by Hodder.

I simply cannot resist

suggesting that for some of the books I have been sent to review, a sick-bag

would have been most welcome, but not this one as it contains some classic

tales by some big names in the horror and science fiction genres. There’s

Stephen King, of course, but also Conan Doyle, Ray Bradbury, Roald Dahl and Dan

Simmons. Particular treats come in the form of Nightmare at 20,000 Feet by the awesome Richard Matheson which made

a famous Twilight Zone episode (starring William Shatner); a prose poem by

James Dickey, author of Deliverance and

the underrated thriller To The White Sea;

and even a locked-room mystery set on an aeroplane by Peter Tremayne – better

known for his Celtic mysteries – which has a lovely Latin tag-line clue.

The anthology is dedicated ‘to

all the pilots…(who) ...brought their passengers home safely. The list includes

Wilbur Wright and Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger and, delightfully, Ted Striker.

Getting

Shorty

I am pleased to discover I am

not alone in being a fan of the television series spin-off of Elmore Leonard’s Get

Shorty.

My talented, and irritatingly

young, chum Vassem Khan (an authority on baby elephants and Cadbury’s Dairy

Milk) has written to share his enthusiasm for the series, declaring Chris O’Dowd’s

performance as ‘a revelation’.

So you don’t have to take my

word for it, and the good news for those already hooked, a second series has

just commenced and is showing (probably) at a Netflix near you quite soon.

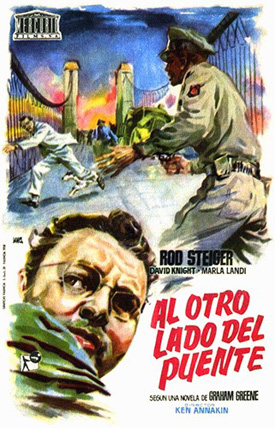

Double

Take

Fellow thriller fans in the

Spanish-speaking world have brought to my attention (in its Spanish release

version) the 1957 film Across the Bridge

starring Rod Steiger and Bernard Lee and directed by Ken Annakin.

Set in the USA and Mexico, but

filmed in England and Spain, I had never come across this film, nor the 1947

short story on which it was based, by Graham Greene.

I was even more unaware that Across the Bridge was remade in 2001 as Double Take, now pretty much a forgotten

film (mercifully, I am told) and which had absolutely nothing to do with the

equally-forgotten novel and film script of the same title from 2002.

|

|

Books of the Month

I know nothing about horse racing. Despite Newmarket, its spiritual home, being wisely located in East Anglia and despite the fact that for twenty years in a previous life I worked in the same building as The Jockey Club, my ignorance is breath-taking. When it comes to picking winners, I could not tip more rubbish with a JCB. I am therefore eternally grateful to the late Dick Francis and now his son Felix, for supplementing my education on the sport of kings.

Crisis is the latest Felix Francis thriller, published later this month by Simon & Schuster. Its hero, Harry Foster, is a lawyer who knows as little about horse racing as I do, but as the legal practice he works for specialises in crisis management, when a crisis occurs at the Newmarket stables where his oil-rich Middle-Eastern client keeps his race horses trained by the Chadwick family, the reluctant Foster is despatched.

And what a crisis he faces when he gets there: a stable fire has killed, most horribly, seven horses including Prince of Troy, a dead cert for the upcoming Derby. As the investigation progresses, the charred remains of a human body are found among the debris and the Chadwicks are put in the frame for murder. From that moment on, its odds against Foster having an easy time of it and the plot comes to a flying finish as he uncovers a crime in which the Chadwicks are involved up to the hilt; a real blood sport even more shocking than the slaughter of valuable bloodstock.

First the good news. There’s a new ‘Jimmy Perez’ novel by Ann Cleeves, Wild Fire, out this month from Macmillan. The bad news is that it is said to be the last of her highly successful series set in the murderous Shetland Islands (they’re lovely, really).

Ann, who hosted the inaugural Shetland Noir festival in 2015, has said: ‘It’s back to Shetland one last time! The place and the novels that have changed my life. This is a bittersweet moment in my writing career: the last of the Jimmy Perez novels; a way of tying up loose ends and celebrating my relationship with these extraordinary islands.’

Fans will be delighted with the book and furious with the news, until they hear that a fifth series of the BBC adaptation Shetland starring Douglas Henshall, is now in production.

In July I reported on a new edition of Lynda La Plante’s trail-blazing thriller Widows coming out to coincide with the upcoming film version scripted by Gillian Flynn. This month sees a new novel, Murder Mile, from Zaffre, which harks back to the early career of possibly Lynda’s greatest creation, Jane Tennison of Prime Suspect fame.

The setting is 1979 and the ‘winter of discontent’ which heralded the rise of Margaret Thatcher. Jane Tennison, now a detective sergeant, has been posted to Peckham in south London but she has more to worry her than dodgy market traders driving Reliant Robins, when two bodies turn up in as many days suggesting a serial killer is on the prowl on Peckham’s very own Murder Mile.

For the more academically-minded reader of this column (and there must be one somewhere) with an interest in the work of James Ellroy, that tenacious chronicler of America’s dark side, then I can do no better than recommend The Big Somewhere published by Bloomsbury Academic.

Edited by England’s premier Ellroy scholar Steven Powell, The Big Somewhere is a collection of essays on all aspects of ‘Ellrovia’ by academics from the universities of Liverpool, Manchester, Surrey, Munich and Sydney as well as the much-respected (for its interest in crime fiction) Wheaton College, Massachusetts.

In his introduction, Steve Powell notes that ‘Scholarly material is now being produced at a fairly steady rate, yet it has not impeded the author. Ellroy shows no signs of winding down…’ Unfortunately his fans will have to curb their enthusiasm for a little while yet, as his new novel This Storm, scheduled for UK publication this month, has been delayed until May 2019.

Budding undergraduates in the study of this important figure in crime fiction be warned, however, for the advancement of learning comes at a price. Bloomsbury Academic are asking £88 a copy for this fascinating piece of scholarship.

That devilishly handsome Italian lawyer turned politician turned crime writer Gianrico Caroliglio will, I am sure, have no trouble attracting a mass audience to hear him speak at Waterstones in Bath and at the Italian Cultural Institute in London (whose hospitality I can attest to) later this month.

Ironically as Gianrico is a former prosecutor specializing in anti-Mafia activities, I will be unable to attend either session as I will be in Sicily on family business. The reason for his visit to the UK is to mark the publication of The Cold Summer by Bitter Lemon Press, which introduces a new series hero and setting: Pietro Fenoglio, a Carabinieri officer in Puglia, which Gianrico knows well (he was born in the capital Bari), in 1992, when Mafia violence erupted across the region.

It seems that a new ‘forgotten’ author from the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of English crime fiction is being republished every month, all of them billed as ‘masters’ of the genre; forcing me to admit that I had never heard of them but never quite daring to ask if there might be a good reason why their books had been out of print for 70 years or more.

However, with the splendid new collection of ‘lost tales’ entitled Bodies From The Library, edited by Tony Medawar and published by the famous Collins Crime Club, I am well within my comfort zone. Of the 16 stories in this excellent cocktail of crime, there are only two authors I am unfamiliar with – J.J. Connington and Vincent Cornier if you have to ask so that you can hold it against me.

I am sure they fit comfortable alongside some of the real masters featured here, including: Agatha Christie, Anthony Berkeley, Cyril Hare, Christianna Brand and A.A. Milne, plus other splendid writers not automatically associated with the ‘Golden Age’ (at least in my mind) such as Roy Vickers, Arthur Upfield and the wonderful Leo Bruce (a ‘Sergeant Beef’ story from 1952).

Tony Medawar’s pithy and perceptive introduction pays generous tribute to the ‘continuation novels, which aim to sustain the traditions of the Golden Age by reviving some of its best loved characters’ naming Jill Paton Walsh (Wimsey), Sophie Hannah (Poirot), Stella Duffy (Roderick Alleyn) and myself (Albert Campion). It also praises the annual Bodies from the Library conference held at the British Library which, for legal reasons, I have never attended, otherwise I might have known who Messrs Connington and Cornier were.

A real vintage re-issue, pre-dating even the ‘Golden Age’ (though it was republished during the Golden Age by the Detective Story Club) first appeared in 1901 but now comes as one of Collins Crime Club’s superior small hardbacks at the ridiculously reasonable price of £9.99.

Many will have heard (or should have) of Fergus Hume’s first novel The Mystery of a Hansom Cab which was an international (translated into twelve languages) bestseller in 1886, famously overshadowing the debut of a certain Sherlock Holmes. Fergus Hume never managed to repeat that success despite writing more than one hundred further novels and is often dismissed today as a ‘one hit wonder’.

Although cited in every history of crime fiction, very few people today can say they have read The Mystery of a Hansom Cab. I have, and I thought it jolly good. Even fewer, myself included, would claim to have read The Millionaire Mystery, which features a vagabond philosopher, Cicero Gramp, as the amateur sleuth; but now I can.

Arriving too late for me to give proper consideration, two paperback originals have caught my eye, though neither – at first glance – are books which would normally find their way on to my towering TBR pile.

I am not a great fan of science fiction, but I was intrigued by the pitch for One Way by S.J. Morden (Gollancz), where a select group of convicts facing death sentences on Earth are exported to Mars to construct the first permanent base. Perhaps not surprisingly, there’s a murderer among them and suspicious deaths follow, from which there is literally no escape. I wonder if Ten Little Martians was ever considered as an alternative title.

The Tattoo Thief, the debut crime novel from Alison Belsham, published by Trapeze, presents a difficulty for me featuring as it does a serial killer who removes tattoos from his victims’ bodies whilst they are still alive. Now I’ve had a very squeamish attitude to tattoos since, as a student, reading the transcripts of Nazi war crimes trials and the allegations against Ilsa Koch about lampshades, then later the gruesome true stories about Ed Gein, the inspiration behind Robert Bloch’s Psycho. However, I may well give it a go as the novel is set in Brighton, which is rapidly becoming the (fictional) murder capital of England now that Oxford has gone quiet.

Rebus Advanced

For reasons I do not understand, as the rules of British publishing are as mysterious to me as the laws of physics, the new John Rebus novel by Ian Rankin, In A House of Lies will be available from Orion on 4th October and not the 18th, as previously advertised.

Having been treated to an advance proof copy, I can say, without giving too much (if anything) away, that it is very good; and Ian Rankin makes writing this sort of policier look so easy, it’s no wonder I hate him.

My proof copy comes with the tag-line A Good Lie is as Hard to Find as the Truth and I am considering stealing A Good Lie is Hard To Find as a title for my own use if somebody out there has a spare plot I could borrow.

One thing did slightly worry me in House of Lies, in a scene where John Rebus is visiting the home of a fellow retired policeman. Rebus is examining a bookshelf full of paperbacks and comments: ‘You don’t hear much of Alistair MacLean these days’.

Now that’s interesting. If only someone would write a book about great British thriller writers in their heyday of the 1960s and 70s before such names as MacLean slip from popular memory. I’d give such a book a prize.

The Graham Mystery

Last month I appealed for enlightenment as to the title of Winston ‘Poldark’ Graham’s ‘other’ spy novel and my Inbox was flooded with suggestions, several of which actually had something to do with Winston Graham and with books. (Many had to be dismissed as either illegal or physically impossible.)

There were, however, a number of sensible candidates put forward; the most likely coming from Geoff Bradley, the editor of that learned journal CADS, who suggested No Exit, Winston Graham’s 1940 novel featuring an English engineer on a business trip to Romania at the start of WWII who gets involved with the nascent resistance movement against the Nazis.

As the only copy of No Exit I could locate on the jolly old interweb is in America and for sale at £1,300, I cannot be sure, but this does sound like it. Of course I could wait until after Brexit and then offer 13 Euros.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster.

|