|

Goldfingered

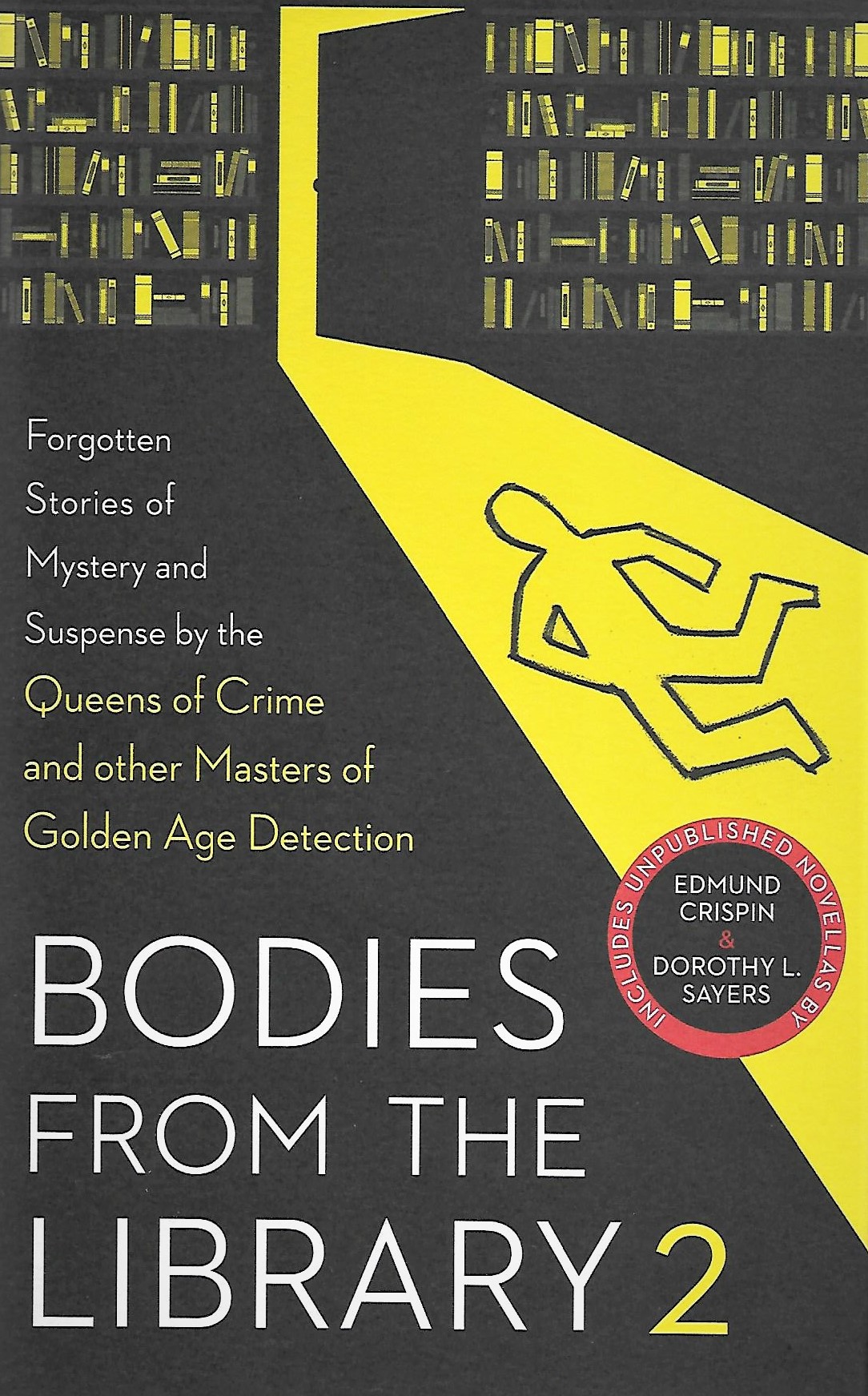

There have not been many occasions when I have been name-checked in a book which celebrates ‘Masters of Golden Age Detection’ or at least not in terms which could be repeated on a family website. Yet I find myself mentioned in Bodies from the Library 2 now published in the iconic Collins Crime Club imprint.

The editor of this collection of ‘forgotten stories of mystery and suspense’ is Tony Medawar, who generously acknowledges my efforts in continuing the adventures of Albert Campion, the Golden Age sleuth created by Margery Allingham who, of course, features in the anthology in her own glorious right.

She is in very distinguished company, alongside Christianna Brand, Agatha Christie, Ethel Lina White, Dorothy L. Sayers, E.C.R. Lorac, S.S. Van Dine and John Rhode, all names familiar to students of the era. And Medawar includes, rather cheekily, some surprises.

There is a story by ‘Peter Anthony’ a joint-pseudonym used by the twin brothers Peter and Anthony Shaffer who are better known for plays and film scripts such as Sleuth, Frenzy, The Wicker Man, Equus and Amadeus. There is also a rare short story by American Jonathan Latimer, who is better known for fiction slightly more hardboiled than traditional Golden Age fare.

The prize gems of this entertaining and informative anthology, though, must be a previously unpublished novellas by Dorothy L. Sayers (featuring Lord Peter Wimsey) and by Edmund Crispin (featuring Gervase Fen). If for those alone, it is worth stepping over the bodies in the library to grab this volume off the shelf.

Time’s Arrow

I remember once reviewing a crime novel and expressing surprise (and a wee bit of outrage) that it had been written by an author who was born after The Beatles had split up. Such a flagrant flaunting of youthful energy was, I felt at the time, a slap in the face – or a patronising pat on the head – to the elder statesmen and women of crime fiction who has served their apprenticeships in life properly and not started writing until they were old enough to drink. In other words, I was furiously jealous.

Nowadays I am much calmer (the cardio-therapy helps) and relaxed about such things, which is just as well, for I have discovered a crime writer who was born after the invention of the Internet. {I am told by a geeky sub-editor that technically this should be after the invention of “the World Wide Web” but I have refused to correct it on the grounds that it may appear as if I knew what I was talking about.}

Fortunately, Sam Hurcom has set his debut gothic thriller A Shadow on the Lens, outnext month from Orion, in 1904 during the early days of forensic photography. I expect, therefore, to find much that is familiar to me.

Possibly Misheard

I realise now that I reacted over-hastily at a recent cocktail party at the Victoria & Albert when I was accused of being ‘under the influence’. Fortunately the damage was limited to a dropped tray of kiwi fruit martinis, a small statue (probably a copy) knocked off its plinth and injuries which really did not merit the attention of a paramedic, let alone the police.

If was, of course, all a misunderstanding as a genuine well-wisher had actually complimented me on being ‘an influencer’ and I had misheard. Not that I am any wiser knowing that. I am told that ‘influencer’ is now a respectable term for ‘blogger’, though I was never quite sure what a blogger was.

If it means that my Getting Away With Murder in the upstanding organ that is Shots influences readers in their purchase of crime fiction, then I was made aware of that some years ago. The much-missed Ariana Franklin, who died in 2011, used to send me regular emails along the lines of ‘Your ****ing column is costing me a fortune by recommending all those good books’ and were something of a source of pride. I have also been asked to remove more than one established crime writer from my mailing list on the basis that ‘seeing all the competition out there’ was so depressing, it was damaging their health.

Being an interweb ‘influencer’ is, I am told, a prestigious and profitable thing to be today, though I am not convinced, certainly not on the profit aspect. After all, I have been mentioning my own novels for years.

Talking Pictures

On a recent tour of the servants’ quarters here at Ripster Hall, I discovered my old factotum Waldo in his butler’s pantry, which he rarely leaves these days, watching the small black-and-white television I presented him with on his 80th or 90th birthday.

He has discovered that there are actually more than four television channels now, if fact quite a lot more and his favourite is something called Talking Pictures which specialises in showing old films. Two in particular caught my eye and, briefly, my attention:

Released in 1967, The Deadly Affair was, of course, adapted from the early John Le Carré novel Call for the Dead and starred James Mason as George Smiley, except it didn’t. For Byzantine contractual reasons (because The Spy Who Came in from the Coldhad already come out), the character’s name had to be changed to ‘Charles Dobbs’. Another curiosity about the film is that several scenes take place in a theatre staging plays by Shakespeare and Marlowe, and the on-stage thespian taking a lead role is an uncredited David Warner, who was riding high in the popularity stakes at the time following his role in Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment, one of the cult films of the Swinging Sixties.

I have to admit I had not seen, nor even heard of, Sewers of Gold, a heist movie set on the Riviera and starring a pre-Lovejoy Ian McShane as a right-wing French paratrooper robbing a bank to fund his fascist organisation’s crusade against communism! The film was also known as Dirty Money, and probably a few other choice epithets by those who paid good money to see it back in 1979.

Waldo tells me that he has recently tuned to Channel 81 (81 – who knew?) and enjoyed the sadly overlooked Frank Sinatra thriller Suddenly from 1954, which I heartily recommend, and Joseph Losey’s rather bizarre 1968 version of Modesty Blaise, which I do not.

The Elephant in the Room

The traditional, sometimes called ‘cosy’, murder mystery should have, by common consent, certain familiar and identifiable features: an interesting and sympathetic central character as the detective; a well-defined setting, preferably an exotic one unfamiliar to the reader; a cultural or psychological sub-text which interests and informs the reader; a smattering of humour; the ultimate triumph of justice; possibly as cipher or coded message to unravel, and, of course, a baby elephant.

Bad Day at the Vulture Club by Vaseem Khan, published this month by Mulholland, has all these attributes: a sympathetic (private) detective in the form of retired policeman Ashwin Chopra, the fabulous setting of modern India where ancient belief systems clash with high-rise developments, some excellent jokes (including some mother-in-law gags new to me) and a coded message left by a murdered man in a book of poetry. Oh yes, and there’s a baby elephant. In fact, Baby Ganesh, a young calf accidentally adopted by Chopra four books ago, might be regarded as the lead character of the series and I now understand when young people say “OMG” they mean “Oh My Ganesh”.

There is even an occasion in his latest outing, where Ganesh saves Chopra’s life in an outrageous riff on the famous scene where Lassie reports that Timmy’s fallen down the well. Baby Ganesh seems to have overcome an addiction to Cadbury’s Dairy Milk, but is bound to keep growing and surely will become too big to travel in the back of Chopra’s van.

Until then we can revel in their adventures and learn much about life and death in India and, in this case, about Parsees and their rather specialist funeral rites which involve (and the clue is in the title), vultures. To call Vaseem Khan’s crime novels ‘cosies’ is probably inaccurate as Khan doesn’t pull any punches when contrasting Mumbai’s growing number of billionaires with the staggering poverty of the city and the problems that produces, nowhere better illustrated than in the ‘Poo2Loo’ campaign described here, along with references to a fearsome police unit known as the Encounter Squad. But cosy or not, they are certainly entertaining and slip down smoothly like a fine malt whisky.

On the Campaign Trail

Two years ago I was asked to write and record a short lecture for the Home Service, or BBC Radio 4 as they now insist on calling it, on how old British thrillers might still be relevant today, thirty or more years after they were bestsellers. One which sprang to mind – though I cannot possibly think why – was Ted Allbeury’s 1980 conspiracy thriller The Twentieth Day of January which postulated the idea that a candidate in an American Presidential election was a Russian ‘mole’.

In some quarters, my little talk (broadcast late one night with little fanfare) caused a bit of a stir and the name Ted Allbeury, one of our finest writers of spy-fiction, began to crop up in newspaper articles after lying disgracefully dormant for too long, and indeed his ‘Inauguration Day thriller’ was brought back into print last year.

I should probably have also mentioned Owen Sela’s 1988 take on the same premise of Russian control over the White House, The KGB Candidate, which should not be confused with the more recent final part of the ‘Red Sparrow’ trilogy, The Kremlin’s Candidate, by former CIA officer Jason Matthews.

The Trevor Memorandum

In the recent heatwave I set myself various reading challenges as I settle on my sun lounger next to the ornamental pool specially constructed to keep my supply of Rosé de Nîmes at the correct temperature. For July I chose two novels, one published in the year before I was born and one in the year my first novel was published.

Both were written by the same person under different names, one of which was his real name – sort of.

Trevor Dudley-Smith (1920-1995) had written some thirty books, mostly ‘young adult’ fiction as we would say today, by the time Tiger Street was published in 1951 under one of his many pen-names. He like the sound of Elleston Trevor so much that he eventually legally adopted it as his real name, then almost immediately went on even greater success under the name Adam Hall.

Tiger Street is not really a thriller, although Trevor was starting to write them at this time, but more a novel of ‘social realism’ almost a precursor of the ‘kitchen sink dramas’ of the mid-1950s. It is set over a period of three hours in a bomb-damaged enclave of West London in the immediate post-war years, where women wear ‘high-heeled ‘Barbara Stanwyck’ step-outs’ or a ‘three-guinea cotton ‘Lana Turner’ two-piece from the Hollywood shop in Edgeware’. There are crimes in the story, but they are not there as mysteries to be unravelled, they just happen to the large cast of floating characters. It is actually a fascinating snapshot of life in 1951 and worth reading for the period detail alone.

I was particularly pleased to see London taxi-drivers referred to as ‘mushers’ in print. When I once attempted to insert that historically valid term into a novel it resulted in a stand up row with a very young copy-editor who claimed I was making it up.

By 1988, Elleston Trevor had enjoyed tremendous success with one-off thrillers such as The Flight of the Phoenix, and become an international player in the spy-fiction boom thanks to his creation of super-spy Quiller.

Quiller’s Run was the twelfth outing for the indestructible Quiller, here on a freelance mission to south-east Asia. It appeared exactly at the same time as my first crime novel, which is probably why I missed it, but I am delighted I have finally got around to it as it is a fantastic, rip-roaring read with an exotic setting, a realistic arms-smuggling plot, much paranoid spy ‘tradecraft’, a ruthless (female) villain and a real and scary ‘heart of darkness’ interlude deep in the Cambodian jungle. And, of course, there’s Quiller, the ultimate agent (who avoids guns wherever possible) who relies on his nerves – and what nerves!

To describe Quiller to anyone who hasn’t read the series published between 1966 and 1995 (and why haven’t you?) is difficult to do in a few words, but suffice it to say that the ‘Jason Bourne’ of the films owes an awful lot to Quiller.

|

|

Books of the Month

Narrative voices in crime fiction are reliably unreliable these days and one can’t really trust anything that any character says, even if they are a lawyer – or should that be especially if…?

The underlying premise of Don’t Say A Word by Rebecca Tinnelly, out now from Hodder, however, is that the characters don’t say enough about past crimes, either through guilt or shame or trauma, which leads inevitably to seismic revelations, retribution and murder. The story has sexual grooming and abuse at its heart, spread over half a century, and how the main characters, all female, suffer it, cope with the knowledge of it or live in blissful ignorance of it. The setting, mostly an isolated rural Somerset village dominated by twin hollow towers of grain silos, is cleverly evoked and the scene of a slightly surreal climactic fight and chase. The plotting is intricate, the suspense gradually turned up to eleven, and the tone darkly convincing, with several genuinely shocking moments. Don’t Say A Word, Tinnelly’s second novel shows a writer firmly in control of her subject matter and is not afraid to tackle the horrific (and seemingly horribly mundane) actions of a manipulative predator, but also issues of mental illness and palliative care. There is also an ingenious method of murder involving…but no, I mustn’t say a word. guilt or shame or trauma, which leads inevitably to seismic revelations, retribution and murder. The story has sexual grooming and abuse at its heart, spread over half a century, and how the main characters, all female, suffer it, cope with the knowledge of it or live in blissful ignorance of it. The setting, mostly an isolated rural Somerset village dominated by twin hollow towers of grain silos, is cleverly evoked and the scene of a slightly surreal climactic fight and chase. The plotting is intricate, the suspense gradually turned up to eleven, and the tone darkly convincing, with several genuinely shocking moments. Don’t Say A Word, Tinnelly’s second novel shows a writer firmly in control of her subject matter and is not afraid to tackle the horrific (and seemingly horribly mundane) actions of a manipulative predator, but also issues of mental illness and palliative care. There is also an ingenious method of murder involving…but no, I mustn’t say a word.

Although I have not seen a copy due to a strict embargo until publication on 22nd August by MacLehose Press, I must mention the fact that The Girl Who Lived Twice by David Lagercrantz promises to be the last in the second ‘Millennium’ trilogy originated by the late Stieg Larsson. Will this be the last we hear of the tattooed hacker and avenging angel Lisabeth Salander? I wouldn’t put money on it.

Billed as ‘the most exciting thriller launch of 2019’, City of Windows by Robert Pobi, from Mulholland Books, certainly is a thrilling game of cat and mouse across a snowbound New York once it gets going.

In the early part of the book though, I was rather worried that some British readers might feel rather swamped by the regular, rather too-regular, references to American popular culture. Now I am worldly enough, or perhaps just old, to understand phrases such as ‘Vulcan mind-meld’, what the Nakatomi Tower at Christmas was, how someone might possibly ‘Tarzan down a ladder’, what is meant when somebody ‘six-degrees-of-Kevin-Bacon-ed it’ and how ‘doing a Milton Arbogast’ down a staircase could be dangerous. I am also familiar with such distinguished personages as Doc Emmett Brown, Bill Maher and Rufus T. Firefly, but I was blissfully unaware of who Cam Newton, Charles Joseph Whitman, Kato Kaelin or Marino Marini were or indeed are.

There are also the Americanisms which always baffle a European [I am using that word whilst I still can] such as someone having “a 3.7 GPA at UIC” education, pulling up an Aeron, eating “egg cream and a Reuben” (?) and drinking Kombucha. I was also totally baffled by the assertion about a gunsmith called Oscar: “When you see the Prince of Wales attending the annual fox hunt, Oscar’s the guy who customised his shotgun.”(!!!) A sentence wrong on so many levels, all that money spent on The Crown now seems wasted, though who can forget the iconic scene when the Prince rides across that meadow, a shotgun in each hand, to face the fox, shouting “Fill your paws you son of a bitch”? {Spoiler alert: I read a proof of Pobi’s novel. The finished copy has had the reference to the Prince of Wales removed by an eagle-eyed (British) copy-editor. Pity.}

Still, carping aside, City of Windows does deliver quite a thrill-ride as our damaged hero (really damaged), a former FBI man turned astrophysicist is called back to the front line to catch a sniper who seems to enjoy making impossible shots with impossible bullets during winter blizzards, the victims, initially, all being linked to law enforcement. The back story, as revealed, sheds light on America’s inherent problems of gun control (or lack of it), racism, white supremacy and the survivalist mentality of those who want to dispense with government altogether. (We would call that the Tory party here in the UK.)

There is a lot about guns and ammunition (vast amounts of ammo) and a nice twist in the tail (though not a total surprise) as the good guys close in on the sniper. At times, the FBI investigation reminded me of the dramatic police work in Thomas Harris’ Red Dragon and like Harris at his best, Pobi keeps the pages turning.

Any spy novel written by someone called Philby is bound to be intriguing and if it attempts to meld the spy thriller with the current craze for domestic noir, then we should be thankful that someone is trying to do something different with ‘the girl who’ genre.

The Most Difficult Thing, published by Borough Press, is a first novel by Charlotte Philby – and, yes, she is the granddaughter of our most famous KGB mole, Kim. It works better as an exercise in domestic suspense rather than a piece of spy-fi as there is little convincing ‘tradecraft’ and minimal jeopardy for the central character Anna. Is she actually a spy and , if so, who is she spying for and who is she spying on? Accepting, as one must these days, that Anna is an unreliable narrator, she could have mental issues from past trauma and possibly post-natal depression after she gives birth to twin girls. She also has a close relationship with alcohol and, like most of the female characters in the book, is a keen smoker. As a supposedly successful magazine editor and fashion icon married to a rich, socialite lawyer and living in those parts of London where the residents still take taxis rather than Ubers and Nannies outnumber policemen, with holidays in Greece and the Maldives, it is difficult to feel too much empathy with Anna, especially as she’s not a very good spy and as the undercover operation she is involved in stretches over many years, one has to question the value for money she was giving to her spy-masters, whoever they might be. The reader will have more sympathy for the counterpoint narrator, Maria, who enters the story (as a Nanny and, perhaps, reluctant spy) late in the day

By all the accepted norms of the genre, The Most Difficult Thing, doesn’t quite come off as a spy thriller, but does succeed in its portrayal of a woman shackled by deception and deceit, much of it of her own making. But then, aren’t deception and deceit the basic ingredients of the spy thriller?

I am looking forward to reading The Cabin by Jørn Lier Horst, out this month from Penguin, for a number of reasons, not the least of which being that having met him at this year’s CrimeFest, he completely reformed all my misgivings about Norwegian policemen – not that I had many, never having met one before.

The charming and affable Mr Horst not only writes about Scandinavian policemen, notably his Chief Inspector William Wisting, but actually was one before become a successful crime novelist whose books have sold, I am told, over two million copies in Norway alone which, by my maths, covers over 40% of the population. In addition, his books have been translated into twenty-six languages and his Wisting series is, inevitably, being developed for television. All of which leads me to the conclusion that the next time we meet, I know whose round it is. Assuming, of course, that I enjoy The Cabin, which I am sure I will.

It is, amazingly, thirty-one years since I read my first Robert Crais novel The Monkey’s Raincoat, which introduced his Californian private eye duo Elvis Cole and Joe Pike, who were often compared to Robert B. Parker’s Boston-based pairing of Spenser and Hawk.

Robert Crais, now a Grand Master of the Mystery Writers of America, cut his teeth writing for TV shows such as Hill Street Blues and Cagney & Lacey before turning to novels, including some outstanding stand-alone thrillers. His latest though, A Dangerous Man, published by Simon & Schuster, is a welcome return for his celebrated double act of Cole and Pike.

Daniel Silva’s new novel The New Girl, now out from HarperCollins, features his series hero, Israeli spy boss Gabriel Allon caught, once again, in the maelstrom of Middle East politics, which will please their legion of fans. The book comes with a fascinating foreword from the author who, when he started the novel in August 2018, based one of his characters on a certain Saudi Arabian prince who appeared set on modernising and liberalising his country. However, that prince’s suspected involvement in the ghastly murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi embassy in Istanbul, gave author Silva pause for thought and, I suspect, a few revisions.

Graham Hurley’s ‘Wars Within Wars’ series of thrillers set in and around WWII has I feel, gone somewhat under the radar, which is odd as it stands comparison with the work of Philip Kerr and Ben Pastor. His latest, Raid 42, from Head of Zeus, is an immaculately-researched spy story based around the spectacular defection of Rudolf Hess from Hitler’s Germany in 1941. Does Hess come with unofficial peace proposals or is he delusional and his night flight to Scotland part of a wider plot? thrillers set in and around WWII has I feel, gone somewhat under the radar, which is odd as it stands comparison with the work of Philip Kerr and Ben Pastor. His latest, Raid 42, from Head of Zeus, is an immaculately-researched spy story based around the spectacular defection of Rudolf Hess from Hitler’s Germany in 1941. Does Hess come with unofficial peace proposals or is he delusional and his night flight to Scotland part of a wider plot?

Shifting seamlessly from Germany to England to Lisbon (well-known hotbed of spies), Hurley’s story features reappearances of characters from early books, notably Luftwaffe ace Dieter Mertz and his engaging reluctant MI5 agent Tam Moncrieff, not to mention spectacular cameo appearances by Goering, Goebbels and Deputy Fuhrer Hess himself.

Hess spent the years 1941 to his death in 1987 as a prisoner, latterly in Spandau Prison in Berlin, where, for a short time during his National Service, the British medical officer was one ‘Jonathan Gash’ who went on to write the Lovejoy novels. There’s not many people know that.

Neither Lynda La Plante nor her fictional detective Jane Tennison can be said to have gone under anyone’s radar and Lynda’s latest novel The Dirty Dozen, published by Zaffre, is another ‘prequel’ as it were, fleshing out Jane Tennison’s career before she became a National Treasure in the 1991 television drama Prime Suspect.

We are up to 1980 and Tennison is the first female detective posted to the Flying Squad, commonly know as The Sweeney. Cue chauvinist male colleagues, East End gangs, car chases and loud music.

Books of Next Month

It would not be September if we did not see new novels from two of Britain’s most reliable and successful crime writers, Ann Cleeves and Felix Francis.

Having created two award-winning, televised series with her ‘Vera’ and ‘Shetland’ stories, Ann Cleeves is now being just plain greedy and going for a third. The Long Call, published by Macmillan, introduces a new detective, Matthew Venn, and a new setting, North Devon, which for Ann is a positively sub-tropical location.

Felix Francis, nobly continuing the family business started by his father Dick back in 1962, moves into the arena of courtroom drama in Guilty Not Guilty, to be published by Simon & Schuster, though I believe the story begins, or at least I hope it does, on that happiest of Francis hunting grounds, a race course.

|

Reviewing the Reviews

Only a small proportion of the 450+ (?) crime novels published in this country every year manage to get a memorable review from a ‘trusted source’ – i.e. one that cannot be influenced by family connection, blackmail, alcohol or bribery. I am particularly fond of two of mine, almost thirty years apart.

Of my 1990 novel Angel Hunt, that distinguished arbiter of literary merit, Taxi Globe, said ‘Had me rolling on the floor with laughter’ whilst of my latest, Mr Campion’s Visit, Kirkus Reviews in America have declared it ‘Sparkling, sublime piffle’ – exactly the tone I was going for.

Toodles!

The Pifflester

|

|