|

The Autumn Season

The crime fiction London Autumn Season began in the way it has for some thirty years, with a lavish party to celebrate the publication of a new Dick Francis book, although it is now, of course, Felix Francis who is carrying on the family business with Guilty Not Guilty from Simon & Schuster.

Speaking at the event, Felix confirmed that he has been contracted for two more novels and that 2020 will be the centenary of the birth of his father Dick and special events can be expected, along with a statue of Dick Francis at Aintree.

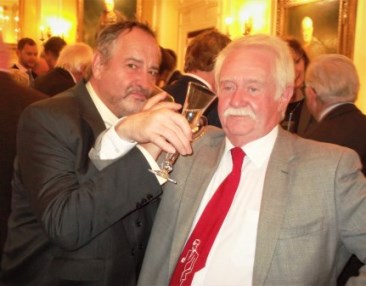

Representing SHOTS at the launch was the voluptuous Ayo Onatade, who quickly discovered Liz Hatherall and Myles Allfrey, who will be well known to delegates to CrimeFest in years gone by. Myles and I were soon reminiscing about CrimeFest’s past and registering our approval of Felix’s choice of champagne.

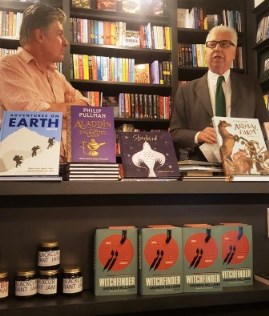

Also in London, in a bookshop in leafy Ladbroke Grove, Andrew Williams celebrated the publication of his spy-fi masterwork Witchfinder with his editor Nick Sayers of Hodder. It was, unbelievably, the first launch party for one of Andrew’s novels, but I suspect it will not be the last.

My early season party-going was rather interrupted by a previous engagement to speak at the plenario session [if that’s the word for the period immediately after lunch] of the Violence in Valpolicella conference in Milan.

But it wasn’t all hard work and the conference gave me the chance to meet up with my old chumette Ben Pastor, the author of the fabulous ‘Martin Bora’ wartime thrillers, and her translator Luigi Sanvito. {A word of explanation here: Ben (Verbena) is Italian but lived and taught in the US for many years. Bilingual, she writes her fiction in English, which is then translated into Italian.}

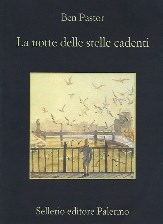

I was delighted to learn that her latest Bora novel (set in Berlin in 1944), La notte delle stele cadenti is to be published in the UK next year under Ben’s original title The Night of Shooting Stars, by which time I will have improved my rudimentary Italian with the aid of my first edition, published by Sellerio Editore of Palermo, who were, incidentally, the Italian publishers of my old mess-mate Colin Dexter.

Christmas Comes Early

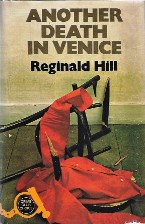

Given the approaching political cliff-edge facing the country at the end of this month, I have taken the decision to hold Christmas early, just in case it’s cancelled. This has involved, as a matter of urgency and importance, drawing up a list of presents I would like. To be honest, I have already jumped the gun and treated myself to a copy of Another Death in Venice by the late, much lamented Reginald Hill.

I first read it shortly after publication in 1976 but having recently visited Rimini and Venice, the twin settings for the novel, I promised myself a re-read, which in the case of Reg Hill is always a pleasure.

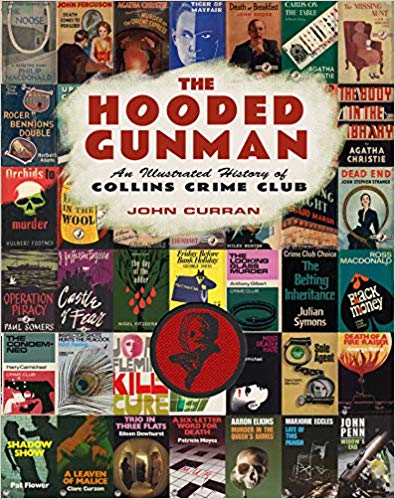

I was always proud to be, like Reg, published by Collins Crime Club but I had never fully recognised what distinguished company I was in until I saw another item destined for my Christmas list, should anyone be checking it twice.

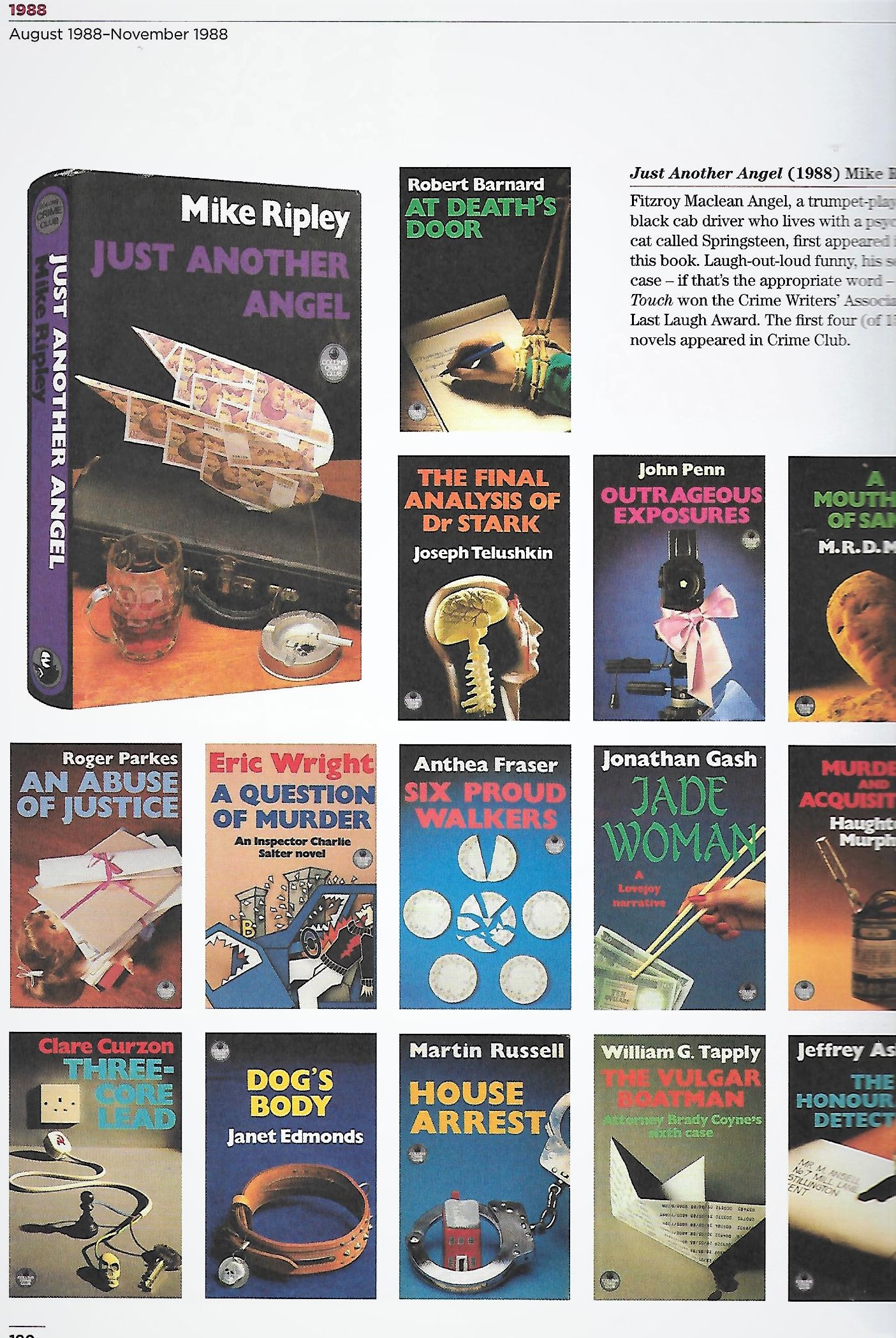

The Hooded Gunman is the illustrated history of Collins Crime Club by John Curran, published by, you’ve guessed it, Collins Crime Club. The cover price is high, at £40, but will stand the test of time as the ultimate reference book for a substantial piece of crime fiction publishing history (1930-1994). And when I say it is illustrated, I do mean illustrated, as it contains not only the dust jacket copy to every Crime Club volume, but the dust-jackets themselves in full colour. There are also added notes about selected titles and authors, though modesty prevents me from picking out an example other than this one purely at random.

Naturally I got to know many fellow Crime Clubbers well after my first novel was published in 1988, among them: Reg Hill, Robert Barnard, Sara Caudwell, Catherine Aird, Marian Babson and Jonathan Gash. And I was, of course, aware of the long history and very famous names from the ‘Golden Age’ who had flourished under the logo of ‘the hooded gunman’, including Agatha Christie, Philip MacDonald and Ngaio Marsh. Yet it took The Hooded Gunman to bring home to me what a fantastic range of talented writers the Crime club championed over seven decades.

Now I am doubly proud that I was a small part of the imprint which was also home to the talents of such as Joan Fleming, Nicholas Blake, Mignon G. Eberhart, Ross Macdonald, Ellis Peters, Rex Stout and Julian Symons.

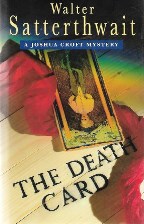

And I must mention my old friend Walter Satterthwait, for I did not know until reading The Hooded Gunman, that his excellent private-eye novel The Death Card was the last official Collins Crime Club title 1994, before the imprint was replaced by Collins Crime. I still have my copy of the book and fond memories of the launch party we held jointly for it and for my (Collins Crime) title Angel City on 24th March 1994 at The Spice of Life, Cambridge Circus in London, the pub most convenient for the Murder One bookshop.

Trick of the Light?

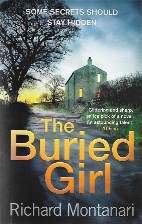

For some reason, probably legal, I missed the hardback of Richard Montanari’s The Buried Girl in February. I am, however, aware of the paperback edition, out now from Sphere, and the cover instantly caught my eye.

As far as I am aware, The Buried Girl is set in a small town in Ohio, which is Richard Montanari’s native state, and revolves around the house recently purchased by New York widower Will Hardy who has moved there. The house and the small town have, unsurprisingly, dark secrets. But what struck me was the photographic image of the house on the cover.

Now to my myopic eye, this does not exactly scream ‘Ohio’ to me. The house, the dry-stone wall and the narrow lane and Autumnal vegetation, all remind me of rural north of England. I would have specified somewhere on the Yorkshire moors, but the fact that the residents have left an unnecessary light burning in an upstairs room rules out Yorkshire. Cumbria, perhaps?

Above My Pay Grade

I realised that I was now out of my depth when I read details of the recent call for papers for a panel in ‘New Perspectives on the Critical History of Detective Fiction’ which I believe to be run by the University of Buffalo in those United States.

The object of the forthcoming panel is apparently:

To move beyond the received sense of critical absence that hamstrings its study… the genre’s scholars must play detective: gather the clues, match story against story, synthesize a narrative that matches and contextualizes the facts. This panel solicits new understandings of the critical history of detective fiction. What are its consensuses and its controversies, its conceptions and misconceptions, its crucial terms, lacunae, and stakes? What can reconstructing its critical history make visible about the genre? What can that reconstruction, and the fact of its necessity, make visible about criticism, its institutional contexts, its methods and practices, and its margins?

Particular points of interest will be:

Detection and empiricism; the pedagogy of popular culture; detection, mass culture, and the Frankfurt School; detection and the canon wars; detection and deconstruction; detection and modes of readership: close reading, symptomatic reading, distant reading, "just reading"; genre and economies of academic prestige; networks and methods of critique: lay criticism, fan criticism, professional criticism, and academic criticism; detection and neoliberalism; detection and the humanities crisis.

Now the only bit of that I really understood was “just reading” and it made me long for the days of yore when, as a panel member, one was asked straightforward questions which one could answer truthfully and pithily, for example:

Q: How do you write your books?

A: On a typewriter.

Q: Where do you get your ideas from?

A: Hanging around in pubs.

Q: Why do you have to use such bad language?

A: F***ed if I know.

|

|

Books of the Month

As a character, Jack Reacher has always reminded me of a warrior figure in the Homeric tradition, meandering his way home from a long foreign war, or the Western hero like Shane who rides into town and stands up for the oppressed. Neither analogy is quite right, as Reacher doesn’t have a home to go to, in fact he’s going nowhere and is in no particular hurry to get there, and his fist fights don’t last as long as Shane’s.

In Blue Moon, from Bantam, Lee Child ups the body count (quite considerably I think) as Reacher rides into an anonymous American city (well, he gets off the bus there), does a worthy piece of Good Samaritanism and almost immediately finds himself in the middle of a war between rival criminal empires. To be honest, Reacher does his best to provoke the war between rival Albanian and Ukrainian gangsters, with several novel uses of cars as weapons and cracking a terrible joke about Kiev along the way.

There are gunfights galore and Reacher shows a very ruthless streak in disposing of the bad guys, never wasting a bullet and there’s even a death by bookcase! The pace is fast and very furious and the whole thing reminds me of the current campaign on the railways and London underground about suspicious packages. The tagline for Blue Moon should be: Got A Problem? – Get Jack Reacher – Sorted.

Due to commitments in Europe (while I still have the chance), I have not yet seen a copy of Martina Cole’s new thriller No Mercy, from Headline. I can confidently predict, even sight unseen, that it will be one of the best-selling novels of the month. More seriously, due to a freakish clash of diary dates (for which somebody will suffer) I find myself unable to attend the launch party for No Mercy, which I think is her 25th novel. Martina’s parties are legendary and missing it will be a sore loss, at least to me, if nobody else.

In a month of big-hitters, I cannot fail to mention the new John Grisham novel The Guardians published by Hodder and it will surprise no-one that it’s about lawyers – a murdered one, twenty-two years ago, and the one now attempting to prove that his killer was wrongly convicted and sentenced to life without parole.

I have never really understood the British reader’s enthusiasm for the highways and byways of the American legal system, but one cannot dispute Grisham’s skill as a storyteller. I particularly like the story, which I am sure is true, that when fans approaching him, as they often do, with the words “I’ve got a great idea for your next book, Mr Grisham”, Mr Grisham smiles and says politely: “So do I”.

It’s good to see the Collins Crime Club imprint back doing what it did best, publishing crime fiction. It was an iconic brand and, fittingly, now publishes the latest adventure of the genre’s most iconic character, Sherlock Holmes, in The Devil’s Due by Bonnie MacBird.

This is a rich stew of Holmesian tropes and lore which romps along with a familiar cast – Watson, Lestrade, Mycroft – bizarre murders (by letter opener), hansom cabs and the protocols of the Diogenes Club, and the added spice of a plot involving French anarchists, Tarot cards and an ‘Alphabet Killer’ learning his ABCs but not getting as far as a character called Zander. The atmosphere for a grimy 1890 London seems spot-on, though I have a niggling doubt about whether the landlord of the Snake and Drum in Spitalfields would have offered Dr Watson a choice of “ale or beer” or whether the very English Watson would have said his destination was “half a block away”. But what do I know? I am no Sherlockian and my knowledge of the Holmes canon is little more than elementary.

An author, or rather two authors, abandoning an established series for a stand-alone novel which has been the buzz of London publishers (and their accountants) is Nicci French, the married writing partnership of Nicci Gerrard and Sean French. They Lying Room, just out from Simon & Schuster is billed, as are so many thrillers which might be loosely termed domestic noir these days, with the epithet ‘how far is she [the central character] prepared to go to protect those she loves?’ Well, if The Lying Room is domestic noir, as it’s written by Nicci French, it will be a superior example.

Already a prize-winner in Europe and soon to be a film starring Isabelle Huppert (whom I remember for her bravura performance in Michael Cimino’s ambitious western Heaven’s Gate), is The Godmother from Old Street Publishing, by French novelist, screenwriter and also criminal lawyer, Hannelore Cayre. Definitely one to watch out for.

In Man on Ice, out this month in paperback from Black Thorn, BBC foreign correspondent Humphrey Hawksley sets his latest thriller in a new Cold War – a very cold war – and introduces one of the most original heroes since Johnny Porter in Lionel Davidson’s Kolymsky Heights.

Captain Rake Ozenna is an elite, special forces soldier and also an Eskimo (and that is the politically correct term in this case), which comes in very handy when a rogue element of the Russian military decides to invade the Diomedes, the tiny (population 8) snowbound islands between Siberia and Alaska. Geo-politics and the tribal and social lifestyles of the local inhabitants clash on the eve of a new American President being sworn in and while political skulduggery takes place in Washington, real violence breaks out in the frozen north, and it really does get violent as Ozenna turns out to be a one-man army, taking on the weather, the ice and the Russians, almost single-handed. It’s good, solid action adventure, reminiscent of Alistair MacLean and Jack Higgins but with the technology updated.

Rake Ozenna reappears in November in a new adventure, Man on Edge, published by Severn House. Once again his special skill set is employed in a hostile climate and on very hostile terrain around the port of Murmansk on the Barents Sea inside the Arctic Circle, just as a high-profile NATO exercise is taking place off the Norwegian coast…

I have to admit I have fallen way behind when it comes to prodigious output of M. T. Trow, whose anarchic ‘Inspector Lestrade’ books were among the funniest fiction around in the late 1980s. In total, since 1985, Mei Trow has published more than 50 novels and at least half that number again of non-fiction titles, mostly on historical or military themes.

One of several of his crime series features the Victorian private eye duo of Grand and Batchelor – one American, one English, which gives scope for solving crimes on both sides of the Atlantic (even though one of them is a martyr to travel sickness) in the 1860s and 1870s. The Black Hills, published by Crème de la Crime, sees the pair way out west in the aforementioned hills of Dakota, acting as unofficial bodyguards to a certain General Custer of the 7th Cavalry, as somebody is trying to kill him – or are they? (In June 1876 there were no end of suspects!) Along the way, our two enquiry agents encounter political corruption, the cavalier treatment meted out to Native American tribes once gold is discovered on their land, an outrageous encounter with President Grant in a White House bedroom and the harsh realities of army life on a frontier posting. the Victorian private eye duo of Grand and Batchelor – one American, one English, which gives scope for solving crimes on both sides of the Atlantic (even though one of them is a martyr to travel sickness) in the 1860s and 1870s. The Black Hills, published by Crème de la Crime, sees the pair way out west in the aforementioned hills of Dakota, acting as unofficial bodyguards to a certain General Custer of the 7th Cavalry, as somebody is trying to kill him – or are they? (In June 1876 there were no end of suspects!) Along the way, our two enquiry agents encounter political corruption, the cavalier treatment meted out to Native American tribes once gold is discovered on their land, an outrageous encounter with President Grant in a White House bedroom and the harsh realities of army life on a frontier posting.

The book is dedicated to the late Doris Day: “the best Calamity Jane there ever was!” and there I beg to disagree. Surely Robin Weigert redefined the role in the TV series and then movie Deadwood, and did it without those sugary songs.

I have been shamefully unaware until now of the work of the prolific American writer Barbara Hambly, my only excuse being that much of her output has been in the sci-fi/fantasy/horror scene, which I must admit is not really my thing. However, since 1997 she has been writing a series of historical mysteries set in the southern states of America in the 1830s and 1840s, featuring Benjamin January, ‘a free man of color (sic)’. The latest, to be published here by Severn House, is Lady of Perdition and it is absolutely fascinating for anyone not familiar with the history of Texas (‘the slaveholders’ republic’) in 1840, before it became one of those United States, and that probably covers the majority of readers in this country, for whom the period is dominated by the mythic status of the battle/siege at the Alamo and historical figures such as John Wayne…

Several years ago I read the journals of a pair of young Irishmen who travelled to the southern states in the mid-1830s, and their account of how they received the news from the Alamo was quite revealing. They, as neutral observers, saw the defenders of the Alamo as ‘brigands’ and ‘pirates’ who were rightly put in their place by the (Catholic) Mexican army. Lady of Perdition is set four years after the Alamo, but Texas is still riven by division between the pro-Mexican population, those who want Texas to join the USA and those who want to keep Texas a ‘free’ state. Barbara Hambly pulls no punches about the desperate need to maintain slavery (which was illegal in Mexico) and the prevalent racist and anti-Catholic sentiments rife at the time. Only with great trepidation does Benjamin January, the free man of colour, venture into Texas on the trail of a kidnapped girl thought to have been sold into slavery. This is an enthralling historical mystery which educates as well as entertains.

Books of NEXT Year!

Publishers seem to be getting ahead of themselves at the moment and are bombarding reviewers with news and even proof copies of books not due to be published for at least six months. These include a new Lynda La Plante, Buried, from Zaffre and The Treatment by Michael Math from Riverrun, both to appear in March 2020 by which time we could have experienced a no-deal Brexit and be grateful for anything to barter with or use as fuel.

The Boulevardiers’ Lament

Recently finding ourselves between social engagements, SHOTS editor Mike ‘Tombstone’ Stotter and I whiled away the early evening in a leisurely stroll around Notting Hill where we chanced upon Mike’s Café, a bijou tea-room which we both felt would be ideal for editorial meetings. Until, that is, we saw the sign which hung over the front door.

At which point, we retired to much more welcoming Goat and Strangler to continue our editorial conference.

Toodles!

The Ripster

|