|

Party Scene

It has been a hectic few weeks on the London social scene starting with the Vintage Crime Showcase featuring forthcoming crime fiction from the Penguin/Random House stable, held in the crypt of St Martin-in-the-Field.

(picture: Jasmine Marsh)

The event featured eight authors ‘in the flesh’ plus Denise Mina over a video link from somewhere north of Watford, among them (fourth from the left) Nicholas Shakespeare, whose ‘literary thriller’ The Sandpit will be published in July next year by Harvill Secker.

Now normally, when I hear the words ‘literary thriller’, that’s when I reach for my Browning, but I was interested to meet Nicholas that night for two reasons. Firstly because I am currently enjoying Six Minutes in May, his authoritative and quite fascinating history of the disastrous 1940 campaign in Norway and the replacement of Chamberlain by Churchill as British Prime Minister. Whilst regular readers of this column may jump to the conclusion, the book has nothing to do with John Frankenheimer’s 1964 film Seven Days in May, although both stories are absolutely gripping.

The other reason I wished to meet Nicholas Shakespeare was that thirty years ago, in 1989, he gave me my first job as a reviewer by appointing me as crime fiction critic for the Sunday Telegraph, where he was then Literary Editor. He has, therefore, a lot to answer for.

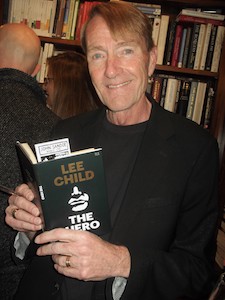

There was a chance to catch up with Lee Child on his visit to the excellent bookshop of John Sandoe in Chelsea to launch The Hero, his extended essay on the nature of the hero figure in myth, folklore and literature written at the behest of the Times Literary Supplement.

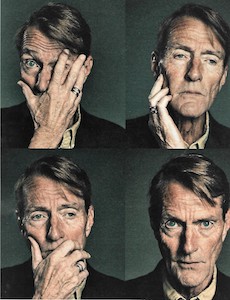

Despite a whirlwind tour of several European centres, Lee found time to appear on Mariella Frostrup’s Open Book programme on Radio 4 with novelist Pat Barker, and to give an extensive interview to The Times colour supplement of 23 November which contained some rather fierce mug-shots of him.

These pictures may be technically first class, but I don’t think they reflect the Lee who is a thoughtful and considerate judge of crime fiction and incredibly generous when it comes to support authors with quotes to be used as ‘cover blurbs’. Which reminds me, I must tell him when my next book is out. (Lee – it’s April. Just saying.)

In blessed relief from pre-Christmas madness, it was a delight, a it always is, to have a civilised lunch with Len Deighton where the table talk ranged from the technology of the fountain pen to the making of the film of Oh What A Lovely War, to ‘forgotten’ (though not by us) authors such as John Masters and Nevil Shute.

And then it was off to the hipster-friendly canal-side area of the Paddington Basin for the annual Christmas lunch of the Margery Allingham Society.

This small but enthusiastic Society, which contains few hipsters, hosts two extremely companionable lunches each year, one to mark Margery’s birthday in May (where the guest speaker traditionally cuts Margery’s birthday cake) and the winter lunch which is held with a portrait of Margery displayed on the top table. The Society also organises a short story competition with the Crime Writers’ Association and talks and visits in East Anglia and London, in particular in one of my favourite venues, the Concert Artistes Association, one of whose pre-war members was Eric Ambler, who came from a family of amateur Music Hall performers.

Down Under Over There

My Australasia correspondent Jeff (‘The Honourable Schoolboy’) Popple tells me congratulations are in order following events at the recent Bouchercon held in Dallas, Texas.

Not only did Jeff win the Don Sandstrom award for lifetime achievement in mystery fandom, but Aussie author Dervla McTiernan took the Barry Award for best paperback original The Ruin. A lawyer in her native Ireland before emigrating to Western Australia in 2011, Dervla’s debut novel was critically acclaimed but, for legal reasons, never crossed my path. I believe she may have a new novel out next year but her UK publisher seems determined to keep me in the dark about that one too.

Treasures of the British Library

That eminent researcher and dedicated advocate for the works of Desmond Bagley Philip Eastwood has, like me, fallen for the seductive qualities of The British Library, where it is impossible not to be distracted from the original purpose of one’s research. In Philip’s case recently, it was spotting an advertisement in a copy of The Booksellerfrom April 1978 promoting the new novel by American thriller writer Ross Thomas, Chinaman’s Chance.

Ross Thomas (1926-1995), who also wrote as Oliver Bleek, was a well-respected author of crime novels and spy thrillers, often with a humorous and slightly left-of-centre bent, which twice won him Edgars from the Mystery Writers of America for Best First Novel (The Cold War Swap) and Best Novel (Briarpatch).

But it was not this reminder of Ross Thomas which distracted Philip Eastwood so much as the face used to promote the book in the advert and on the dust jacket of the first edition hardback, as he recognised it from the days when he made regular court appearances in Kent some years ago.

I should explain. At the time, Philip was a young Bobby on the beat (in those days, he tells me, policemen carried whistles and had truncheon pockets in their trousers) who was used to being in court to follow the fortunes of the miscreants he had arrested. In those courts in the Gravesend and north Kent area, those whose collars had been felt often found themselves up against prosecuting solicitor Cecil Cheng, the man who became the face of Chinaman’s Chance when it was published in the UK.

Apart from his legal life, Cecil Cheng (1925-2002) had an illuminating career not only as a male model for dust jackets, but also as a jobbing actor. He appeared in numerous television shows, among them The Avengers, Department S, The Saint, Jason King and Minder, as well as movies ranging from You Only Live Twice to The Fifth Element. Perhaps his most notable screen appearance though, was as “Number 7” in the hierarchy of the boardroom of SPECTRE in Thunderball.

It must have unsettled many a Kentish villain standing in the dock to see the police prosecution being led by a member of SPECTRE, who were not known for their tolerance or leniency when it came to sentencing.

Memories on the (West) Wind

The reissuing, by Orion, of Ian Rankin’s 1990 techno thriller Westwind has brought back many happy memories, though not of the book (which I never read at the time), but rather of the early days of a struggling writer thirty years ago, which are wonderfully encapsulated by Ian in his introduction to the new edition.

Having written a straight novel, the first Inspector Rebus novel, a spy story and toyed with poetry, Ian turned his hand to what we would now call a ‘techno thriller’ which begins with a space shuttle crashing on landing and, politically, a Britain torn between loyalties to the USA and its continental European neighbours. (That bit sounds a tad far-fetched to me.)

My memories of Westwind actually come not from the book, but Ian’s self-depreciating description of it at one of the first Shots in the Dark conventions in Nottingham in the early 1990s. During a panel session featuring Ian, the late Gwendoline Butler and Janet Neel (now Baroness Cohen) which I chaired, we were, inevitably asked the where-do-you-get-your-ideas-from?question.

I distinctly remember Ian telling the audience that his research into military technology for Westwind had come from a children’s book, which might have been The Ladybird Book of Military Aircraft or I Spy the Cold War in Space; I forget exactly which. I am delighted to find that my memory has not failed me, as Ian, in his introduction, admits that his sources of research material in a public library in Tottenham, were often limited to the children’s section.

Ian’s interest in revising and re-publishing Westwind followed a message from a fan reassuring him that the book was “better than you think it is” which is something a writer always likes to hear and I for one am grateful for the chance to read it, albeit thirty years late.

What the Papers Said

In amongst the rain forest of newsprint devoted to elections, Brexit and the no-longer private lives of celebrities both royal and (dead) common, two items caught my eye which were both worth reading and evangelising about.

In a week-end feature in that once great newspaper the Daily Telegraph, Jake Kerridge, that dashing hipster of crime fiction reviewers, takes to task members of the “literary” establishment who have uttered ‘caustic dismissals’ of crime fiction this year, which he in turn dismisses as sour grapes. He then goes on to pick out more than a dozen of 2019’s outstanding crime novels, many of which had their authors ‘crying all the way to the bank’. (In the interest of balance, I feel I must point out that crime fiction has always been the home of many fine writers who have cried all the way to the food bank.)

I particularly liked Jake’s take (could that be a column: Jake’s Takes?) on Thomas Harris’ Cari Mora: any Harris novel that doesn’t give you nightmares is going to leave you as disappointed as Hannibal Lecter on learning that all the waiters aren’t included in the all-you-can-eat buffet. He also reminds us that, as the late Marcel Berlins wisely used to say, the bulk of the sub-genre most heavily promoted these days, ‘domestic suspense’, are actually rip-offs of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca.

In The Guardian, crime writer Nicola Upson, who employs ‘Golden Age’ crime writer Josephine Tey as her detective in her own fiction, was asked to pick a Top Ten of Golden Age detective stories. Naturally, Josephine Tey features in the list with To Love and Be Wise at #3, and few would argue with her other choices, especially Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (#1), Christianna Brand’s Green For Danger and Margery Allingham’s The Tiger in the Smoke, although, as Upson points out, the latter is more of a psychological thriller rather than a classic fair-play-by-the-rules whodunnit.

Nicola Upson’s feature appeared in The Guardian on 13th November and Jake Kerridge’s piece on 16th November. I am told that both articles may be discovered by searching ‘on-line’ – whatever that means.

Fishy Business

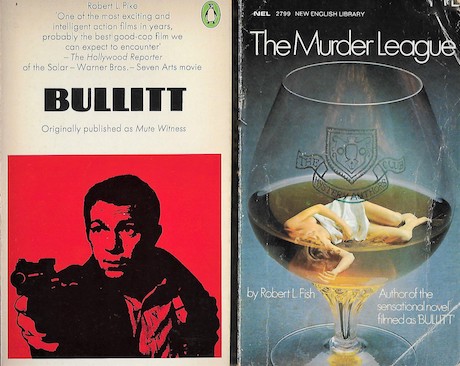

I knew that Robert L. Fish (1912-1981) was a respected American crime-writer who had twice won Edgar Awards from the Mystery Writers of America and is now honoured by them in the memorial award named after him for best first short story.

Of course I was well aware that he used the pen-name Robert L. Pike and that he wrote Mute Witness, famously filmed as Bullitt, but it was only a couple of years ago that I realised he had also written a short series featuring The Murder League, darkly comic novels about crime writers past their prime who turn to murdering people for real and for cash.

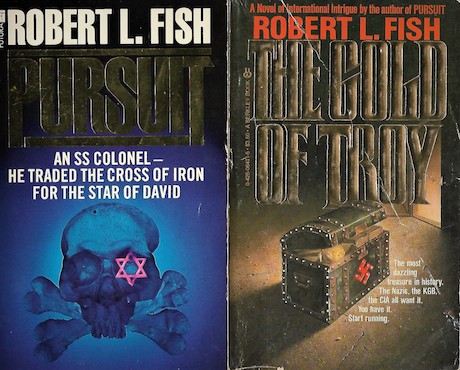

Among Robert L. Fish’s other accomplishments included completing the unfinished Jack London novel The Assassination Bureau and, I have just discovered, that in 1979 and 1980 he turned his pen to action/conspiracy thrillers (usually involving Nazis) of the type which dominated the bestseller lists.

Both Pursuit and The Gold of Troy are impressive vintage thrillers and my admiration for Mr Fish now knows no bounds.

The Golden Age from the Inside

I am not as familiar as perhaps I should be with the novels of Anthony Gilbert, possibly because I have never read one, but I do remember her praises being often sung by my old pal, the late Harry Keating, who was a fair judge of these things. I did know that the name Anthony Gilbert hid, for a long time, the identity of Lucy Beatrice Malleson (1899-1973), and that she was a prolific crime writer firmly associated with the so-called ‘Golden Age’ even though she never achieved the fame, or sales, of Agatha Christie – but then, who did?

In 1940, she published a memoir, Three-A-Penny under another of her pen-names Anne Meredith, which has now been reissued by Weidenfeld & Nicolson with an introduction by Sophie Hannah. It is a fascinating bit of social and feminist history, though in parts frustratingly vague on the nuts-and-bolts of crime-writing, and the title comes from Dorothy L. Sayers, who once told Gilbert/Meredith/Malleson that they may regard authors as “three-a-penny” but “they are quite exciting to other people”, which might strike one as slightly snobbish much as certain modern crime-writers call readers “Muggles”, though never in public.

In her memoir, Malleson recalls her invitation, from Sayers, to join the Detection Club in 1932: Everything snobbish in my system acclaimed this opportunity to hobnob with the Great. And the Detection Club is very snobbish indeed … an association of the aristocracy of the detective-writing world. Conditions of admission were exceedingly rigid; popularity had nothing to do with it. In no circumstances could a thriller-writer be admitted.

Three-A-Penny may be a period piece, but was a fascinating period, and it was written by an intelligent woman who did not lack talent, only perhaps confidence. When one of her novels received rave reviews it seemed a refutation of all one had learned in childhoodbut the book did not sell and Malleson concluded: I was one of those unhappy authors who can please everyone except the public.

|

|

Books of the Month

The new John Le Carré novel, Agent Running in the Field, published by Viking, confirms that there is less to badminton than meets the eye unless, that is, the games are used as cover for clandestine meetings by spies. (I am tempted here to reveal how, when a trainee journalist being recruited for MI6, my ‘handler’ and I agreed to meet under cover of darts matches in the local pub league. My recruitment was terminated after less than a month, however, when the agent ‘running’ me – a southerner – realised he could not get on with Tetleys Bitter, or keep up with the consumption rate of the rest of the team.)

Agent Running in the Field is classic, unmistakeable Le Carré, where brutal martial arts combats are portrayed as seemingly polite conversations between intelligent people. It has the added bonus of some wonderfully vitriolic rants about the stupidity of Brexit, a certain American president and the dismissal of Vladimir Putin as ‘a fifth-rate spy’ – surely the most damning condemnation in the Le Carré lexicon.

And it is Putin (‘and his gang of unredeemed Stalinists’) who is blamed by the narrator for Russia not going forward to a bright future, but backwards into her dark, delusional past, which is a faint echo of the sentiment expressed in the new Boris Akunin novel [see below] about Russia in 1918.

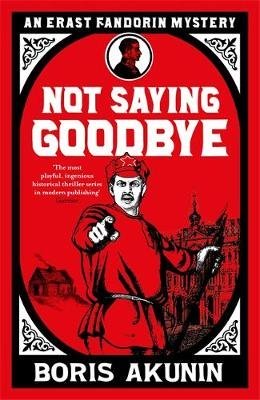

When Boris Akunin’s eccentric Russian detective Erast Fandorin first appeared twenty years ago, he was greeted as a refreshing cross between Sherlock Holmes and James Bond. The Holmesian homage is clear and clearly sincere, but I always felt that Fandorin, with his love of Eastern philosophy, sprung-coil energy and martial arts skills, had more in common with Adam Hall’s special agent Quiller.

I have been lax in following the Fandorin series in recent years and so was unaware of the ‘cliff-hanger’ ending of the last one, that did not, however, spoil my enjoyment of what is billed as Fandorin’s farewell, the perhaps ironically titled Not Saying Goodbye, published with a quite spectacular cover by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. That cover – and this isn’t a Spoiler Alert, or shouldn’t be – indicates that the setting is 1918 Revolutionary Russia into which Fandorin has emerged from a three-year coma. That he finds Moscow somewhat changed is an understatement and our rather groggy hero stumbles, sometimes literally, into adventures with Red Guards, Black Guards, anarchists, Checkists, White counter-revolutionaries, Socialist Revolutionaries, Bolsheviks and major and minor criminals in between.

Fandorin’s aim is to follow his Japanese sidekick Masa out of ‘a country that wishes to exchange a bad past for an appalling future’ and his struggle, often with tongue firmly in cheek, is as audacious as it is entertaining. For anyone completely ignorant of Russian history, there may be a few stumbling blocks (even I had to look up what an ‘artel’ was) and, amidst much to savour, there was one jarring note, when Masa’s Japanese accent is transcribed in a pure Benny Hill “velly solly” voice. At one point, he says that his master (Fandorin) ‘has been in a deep, deep sreep for more than three years. He srept through the war and he srept through the revolution.’ But then, despite the various revolutions, there was less political correctness back in 1918.

That Abir Mukherjee is a rising man of historical crime fiction is not in dispute with his popular novels set in the India of the 1920s, and I like to think of him, on fairly recent acquaintance as a chum of mine. I am sure, therefore that he won’t mind being taken to task on a couple of points about his latest novel Death in the East, from Harvill Secker, although neither should spoil anyone’s enjoyment of the book, which is both clever and very readable.

The novel comes, if one is lucky, with a promotional bottle of pale ale with a label proclaiming the punning name Death in the Yeast and I have to point out given my experience in the brewing trade in a previous life, that no sane brewer would ever joke about death in his yeast, or the infection which I think used to be covertly referred to as ‘rope’, but never in the earshot of the drinking public.

My other niggle is that in one of the intriguing flashback scenes to Whitechapel in 1905, a character is described as having ‘the sharp features of a Boudicca’. Now I can forgive, in the context of 1905, the mis-spelling of Boudica as they would not have been aware of the recent revisionist trend in archaeology, but then in 1905, wouldn’t they have used the popular (but inaccurate) Victorian term Boadicea? Just a thought, and a pretty idiotic one at that.

Abir opens his latest with his series hero, Captain Sam Wyndham, one of the Raj’s more sympathetic policemen, en route to an ashram in the hills of Assam in search of a ‘detox’ to cure his opium addiction, which might (or might not) have confused his memories of his earlier life as a fledgling copper in London’s East End.

Purely coincidentally, the hero of David Gordon’s The Hard Stuff (Head of Zeus) is also detoxing, trying to break an addictive habit with the help of a Chinese herbalist. But this is not India, this is present day New York and Joe Brody is no policeman. Except that he is, of a sort. To maintain law and order, or what passes for it, in the New York underworld, an alliance of the numerous gangs and mob bosses have appointed Joe their ‘sheriff’, partly due to the threat of fundamentalist terrorist cells operating on their turf, for they are nothing if not patriotic mobsters.

As Joe is an ex-Black Ops specialist now working as a strip club bouncer, he is ideally, if reluctantly, suited to the task even though he is dogged by pursuing FBI agent Donna Zamora to whom his feelings are not exactly professional (and the same goes for her). The plot involves a new drug dealer in town, and a possible Al Qaeda splinter cell looking for diamonds to fund a terrorist atrocity, all of which might disrupt the regular business of organised crime.

The action pops and crackles and the dialogue – particularly amongst the various gangsters – positively zings. The Hard Stuff is a fast and furious crime caper which reminded me of the crime novels of one of my favourite American writers of about twenty years ago, Doug J. Swanson.

There was a time – I will not say ‘when I was a lad’ – when the outline of a nuclear submarine on the cover of book indicated a good action-adventure thriller; think Ice Station Zebra, or Antony Trew’s Two Hours To Darkness or Stephen Coulter’s Threshold or Geoffrey Jenkins’ Hunter Killer, and didn’t Tom Clancy write one about a Russian one…?

Now Michael Ridpath, who has shown he can write thrillers in numerous styles (including some of the best Nordic Noir around), brings back some fond memories as well as making the hairs on the back of the neck stand up, with Launch Code (Corvus), a modern take on the Cold War thriller.

In the author biography on the dust-jacket flap of The Lady of the Lake, published by Severn House, Peter Guttridge claims that he turned from the Daft Side (comic crime writing) to the Dark Side for his ‘Brighton’ series of mysteries. I’m not too sure I totally believe him.

For a start, there is gentle undercurrent of comedy bubbling away just under the surface of the relationship between his two lead police detectives, Sarah Gilchrist and the slightly Dickensian Bellamy Heap; plus, in his new novel, there’s a body in a lake discovered by a naked swimmer, which reveals Peter’s current obsession with death and open stretches of water (his last book was Swimming With the Dead – enough said). It used to be, in his comic-crime writing days that a Guttridge trademark was something absolutely awful happening to an animal, which probably put him high on the RSPCA’s Most Wanted list. In his latest there is a nod to his long-standing fans in a tangential reference to a police briefing where one of the ‘crimes’ reported concerns a woman’s emotional support guinea pig dying of fright during a fireworks rehearsal for the famous Lewes Bonfire Night celebrations.

Here, and in many other places, Peter is breaking the fourth wall and exchanging sly winks with the reader, especially as he delves into the psyche of a Hollywood film star preferring rural Sussex to L.A. only to find it a no less ruthless and cut-throat environment.

I will make ‘quality time’ this month to read the new novel by Chris Petit, for his thrillers are always most rewarding when read with concentration and a clear head. Mister Wolf(Simon & Schuster) is Petit’s third ‘Morgen and Schlegel’ thriller set in Nazi Germany, ricocheting between the 20th July 1944 bomb plot to assassinate Hitler and pre-war Munich and the unsavoury case of the ‘suicide’ of Hitler’s niece Geli Raubal. This is not new territory for thriller writers but you can bank on Chris Petit to provide, if not a historical reinterpretation, then at least a characteristic Petit spin on events.

Pick of the Year

Two historical thrillers with German heroes, both, in a sense, ‘prequels’ to established series. Philip Kerr’s posthumously published Metropolis takes the reader, and the cynical Bernie Gunther, back to 1920’s Berlin for what was his first, but sadly our last, case. Ben Pastor’s The Horseman’s Song features her hero, aristocratic soldier Martin von Bora, at an earlier, more innocent, stage in his military career in the 1930’s during the Spanish Civil War.

Still on a wartime footing, Alan Furst’s Under Occupation is a skilled and atmospheric novel of the early days of the French Resistance which describes heroism in a calm and totally believable understated way. Furst is a stylist par excellence, making the writing of historical spy fiction look deceptively easy.

For a modern take on the spy story as, dare one say it, Eric Ambler might have written had he been around in the 21st century, Peter Hannington’s A Single Source proved immensely satisfying and brought to mind all the old clichés about new authors ‘jumping the difficult fence of the second novel with ease’.

Pick of the Non-Fiction

Several years ago I was asked by a distinguished thriller writer, whom I much admire, if I would consider mentioning the non-fiction books I had read in my annual ‘pick of the year’ selection, presumably to show that I was a well-rounded human being and not a robot. It is a tradition I have not kept up, but intended to from now on and this year I heartily recommend Dominion by Tom Holland, published by Little, Brown.

Tom Holland (no, not the Spiderman one) is possible the best, certainly the most accessible, historian of the classical world working today, with a growing reputation as a broadcaster. The depth of his source material, both historical and archaeological, is staggering and his skill at assembling and presenting it – telling a story – is first rate. He brings the classical world to life in readable, occasionally wise-cracking, prose and is not afraid to slip in references which an historian of a more staid generation would not have considered, probably not understood. Dominion charts the establishment of Christianity, originally subversive and disruptive, and its lasting influence on the Western world. ‘It is – to coin a phrase – the greatest story ever told’with a core tenet best summed up by Lennon and McCartney.

I noticed, as will certain others readers of this column, that Holland acknowledges a particular (uncredited) source when he uses the phrase ‘I neither know nor care’ but he also comes up with some excellent nuggets of his own, as when describing the letter-writing of the apostle Paul (aka Saul of Tarsus): Sufficiently tutored in the art of rhetoric to deny that he had ever learnt it, he was a brilliant, expressive, highly emotional correspondent.

Continuing on a classical bent, I cannot recommend too highly In The Shadow of Vesuvius, a biography of Pliny the Younger, by that talented and appallingly young classicist Daisy Dunn, published by William Collins.

There is much to learn here about first century Rome in addition to the life of young Pliny, though he was a bit of a dull swot compared to his uncle Pliny the Elder, who fatally insisted on a close-up and personal look when Vesuvius erupted and took out Pompeii.

As Lucius Apuleius, philosopher and putative novelist, said (probably about his own work) Lector intende: laetaberis– ‘Reader, pay attention: you will enjoy yourself.’

Far Side of the World

The name Nalini Singh may not be instantly familiar here in Europe (we’re still in, even if it is pantomime season), but it is in many countries on the other side of the globe.

Born in Fiji, raised in New Zealand and now resident there, although she has lived and worked in Japan and other parts of Asia, Nalini Singh is a prolific author of romantic fiction, romantic suspense, paranormal romance and something called ‘urban fantasy’ (which I used to think covered the Congestion Charge and Boris Bikes). She is a bestseller in these genres in America and has now turned her hand to a claustrophobic thriller, A Madness of Sunshine, published by Gollancz, which is set in the small, remote town of Golden Cove on the west coast of New Zealand’s south island.

Last Word

Last month I noted one of the most unusual titles for a crime novel I had ever come across – The Twenty-Five Sanitary Inspectors – and had a feeling that it would not be the last word on the subject. It wasn’t. I have just discovered The Flagellator by Carter Brown (the British-Australian pulp master, 1923-85) from 1969.

There’s nothing more to say, really.

New Year’s Resolutions

I have long suffered criticism and sarcasm from my junior colleagues in crime-writing and reviewing (which is all of them) for not possessing what I think is called, in modern parlance, a ‘smart’ phone. It is not that I am against mobile phones per se, of course, it is just that I am perfectly happy with my faithful Nokia ‘burner phone’ which I rescued from the set of a Jason Bourne film.

I am more than ever resolved not to replace my battered Nokia having learned, from the last series of the superb police drama Spiral, that the French for a burner phone is un portable de guerre.

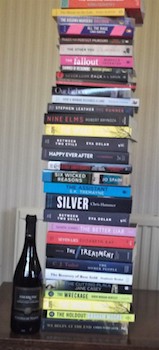

One resolution I may have to make is to tackle the leaning tower of advance proofs of crime novels I have already received for 2020.

For the purpose of scale, I have used a bottle from one of the cases of Amarone I ordered in for the Christmas holiday. Given the height of that pile of proofs, plus a matching one of books I have accumulated during the year and not yet read, I think I will need to re-order.

Having been informed that a General Election is pending, I will perhaps double that re-order.

In the meantime,

Have an absolutely spiffing Christmas,

Ho-ho-ho,

The Ripster.

|