|

So Farewell Then, Lee – But not Jack

My breakfast ritual of reading The Times over toast and a bowl of Mocha-Mysore blend is normally an oasis of tranquillity here at Ripster Hall, even though since the newspaper went tabloid it has been no fun to make the staff iron the morning’s copy before presenting it. However, a bombshell landed on the 18th of January, when the front page announced that Lee Child is to retire at the unreasonably young age of 65.

It is well known, indeed Lee has said in print, that I am ‘a slightly older codger’ than he is, but surely he is too young to be thinking of abandoning a promising career. With 24 novels, numerous short stories, several anthologies edited, two blockbuster films and a television series in the offing, surely now is not the time to quit, just when things are finally starting to look up.

I am sure I said as much to him when we collected our awards at the 2018 CrimeFest in Bristol (I got mine for writing a book, he got his for turning up), hoping that he would take the advice of someone a few months older. I had no qualms about offering Lee my thoughts as I have followed his career with some interest since I, with Maxim Jakubowski, edited Fresh Blood 3 in 1999 which contained the very first Jack Reacher short story.

In addition to his writing career, Lee has also had a notable reading career, praising hundreds if not thousands of books by other authors and always being encouraging. The scale of his reading and his enthusiasm certainly impressed this cynical reviewer, though that may be a factor of age, him being some hours younger than I, and many fledgling authors have been grateful for his endorsement.

Reacher fans, and I believe there are several, should not despair, however, as the series will continue in the hands of Lee’s even more youthful brother Andrew.

M. C. Beaton, Married to a Spy

Whilst writing the obituary of Marion Chesney Gibbons, better known to millions by her most successful pen-name M.C. Beaton, I discovered several things about her journalistic career in Fleet Street in the Sixties which I had not known. As well as reporting, for the Daily Express, on the Profumo/Christine Keeler affair, she once tried to interview Oswald Mosley as he marched with some of his ‘national socialist’ supporters down The Strand. Caught on film by a BBC news crew, Marion was later horrified to see herself on television counted, in the voice-over, as being among Mosley’s ‘loyal followers’.

I was also unaware of her late husband’s extra-curricular activities in his journalistic career until I discovered a fascinating little film on You Tube as part of a series archived on the subject of Kim Philby, his career as a spy for the KGB and his eventual defection to Russia in 1963.

Harry Scott Gibbons, who married Marion Chesney in 1969, was a fellow journalist with the Daily Express, but his beat was the Middle East and in 1958-59 was the newspaper’s correspondent in Beirut. The short film, made I think around 1970 [https://bit.ly/2GEM9uP] recreates Harry’s flirtation with the world of espionage after being ‘recruited’ by the KGB resident at the Russian embassy. Harry Gibbons quickly contacted MI6 in London and became a double agent, passing disinformation rather than solid intelligence to the Soviets. All this at exactly the same time that Kim Philby, also living and working as a journalist in Beirut, was being re-activated as a spy for the KGB.

Harry Gibbons’ career as a double agent ended abruptly, but safely, when his Russian handlers suddenly lost interest in him and the information he was supplying. Clearly his cover as a ‘double’ had been blown by a mole within MI6, though not (for once) Kim Philby, but that other famous KGB spy George Blake, who was revealed as a double agent in 1961 and sentenced to a whopping 42 years in prison. (Blake escaped from Wormwood Scrubs in 1966 and for all I know is still alive and living, aged 98, near Moscow.)

Royal Coincidences

A royal princess forced to leave England to escape a cruel and implacable enemy. Sounds familiar? Substitute the Nazis for the Daily Mail and make that two royal princesses and you have the nub of the plot of The Secret Guests by B.W. Black, published this month by Penguin.

The premise is that during the 1940 Blitz and under the threat of invasion, London is proving far too dangerous a place for the royal princesses Elizabeth and Margaret and the idea is cooked up by some bright spark in Security that they would be much safer hidden away in Ireland. On the face of it, this is a highly unlikely decision as Ireland, only recently having fought its way out from under British rule, still seethes with anti-British and pro-German feeling and has opted for neutrality during WWII. {One wag in the book raises the question, with very Irish logic, ‘Who does that mean we’re neutral against?’)

Everything, of course, must be done in complete secrecy and so MI5 assigns one of their newest and inexperienced recruits as ‘close protection’ (that is quite believable) and naturally, things go wrong. Both sisters do, happily, survive and there is a brief coda set after the war which could form the basis for a lost episode of The Crown.

In one of those spooky coincidences which affect people of great age, my copy of The Secret Guests arrived on the very morning I was filing some old press cuttings and I had just enjoyed reading, for the sixth or seventh time, a glowing review of That Angel Look published in the Irish Times on the 18th April 1998. The generous reviewer who seemed to like my book was the journalist Vincent Banville, the elder brother of novelist John Banville, who uses the name Benjamin Black – and now ‘B.W. Black’ – when writing crime fiction.

A Real Honey

My South American correspondent, in a recent piece of nostalgia, has reminded me of my youthful admiration for that ground-breaking female private eye Honey West by highlighting the Spanish edition of the 1964 novel Bombshell.

I must admit to not being familiar with the Honey West novels of G.G. Fickling, the joint pen-name of husband and wife team Gloria and Forrest Fickling, of which there were eleven in total, starting with Honey’s debut in This Girl for Hire in 1957. My admiration was rather for the television series of 1965-66 though not so much for the plotting or production values but because I had something of a boyhood crush on Anne Francis.

Yet my crush started before I ever saw Honey West the TV show, with the actress’ sterling performances in films such as The Satan Bug (above), the Shakespearean sci-fi classic Forbidden Planet and that superior modern western Bad Day at Black Rock.

Kind Editors and Coronets

Those charming and energetic ‘Golden Age’ enthusiasts at the Dean Street Press are continuing their quest to rescue the fiction, and hopeful the reputations, of some overlooked if not forgotten authors with new editions of titles by Moray Dalton and Henrietta Clandon (no, me neither). I was, however, already aware of the work of married couple Edwin (1890-1973) and Mona (1894-1990) Radford, admittedly only thanks to the Dean Street Press, who wrote novels featuring their doctor detective Harry Munson between 1944 and 1972.

This latter date suggests that the ‘Golden Age’ extended into my university days, but I will let that pass in order to recommend the Radfords’ 1959 novel Death of a Frightened Editor, which is fast becoming one of my favourite titles and is a phrase I will undoubtedly employ in the future.

The real star, though, in the new Dean Street list for 2020 predates the ‘Golden Age’ and is a book which provided the source material for one of the greatest of the Ealing Comedies – now there was a golden age…

Kind Hearts and Coronets, the classic 1949 black comedy and perfect satire on the English class system, was based on the 1907 novel Israel Rank by the actor manager and screenwriter Roy Horniman (1972-1930). The famous film (one of my three favourite films EVER!) follows the book in detailing the narrator’s rise to a dukedom by murdering all the family members who are in line ahead of him and, at the time, the novel was very much an attack of the anti-Semitic attitudes of the British establishment. The film, made in the aftermath of WWII and revelations about the extent of the Holocaust, chose to make the protagonist half-Italian rather than half-Jewish, but did not pull its punches when exposing xenophobia and snobbery. It is also famous for Alec Guinness taking on all eight roles as murder victims without, happily, any of the concomitant crudities….

Anyone who does not understand that last sentence should see the film as a matter of cultural emergency. It is shown often enough on terrestrial television and I understand that a 70th anniversary edition was released on DVD and Blu-Ray (whatever that is) last year. I did not know, until recently, that on its original release in those United States, the wonderfully enigmatic ending was changed in case American audiences got the impression that crime really did pay.

Waiting for the Minibus

I have been on the lookout for a copy of The Allingham Minibus for many months, ever since overhearing two veteran Margery Allingham fans discussing their favourite among her short stories and agreeing on The Wink, which is one of the stories in the ‘Minibus’ collection, first published in 1973, several years after the author’s death.

With immaculate timing, as far as I was concerned, Agora Books have produced a new paperback edition of The Allingham Minibus which contains eighteen stories, three featuring her famous detective Albert Campion, but most ranging over the ghostly as well as the ghastly.

Allingham always gave a distinct shape to everything she wrote, at whatever length and during the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of English detective stories, her novels stood out ‘like a shining light’, but don’t take my word for it; I’m quoting Agatha Christie.

The range of the stories and Allingham’s natural lightness of touch make this an anthology any sane reader would curl up with and enjoy with a few chills and thrills along the way, even though the dedicated Allingham fan would have appreciated some details of when and where the stories were first published (and a Contents Page would have been nice). Recalling the days when short stories were far more popular and the market for them much bigger, The Allingham Minibus makes a fascinating companion piece to Tales on the Off-Beat, the collected short stories of Pip Youngman Carter, Margery’s husband, who collaborated with her on several books, designed the dust jackets for many, if not all, of their UK editions, clearly shared her taste for the spooky and supernatural as well as the criminal, and who was the first, but by no means the last, continuation author for the adventures of Albert Campion.

Cover Up

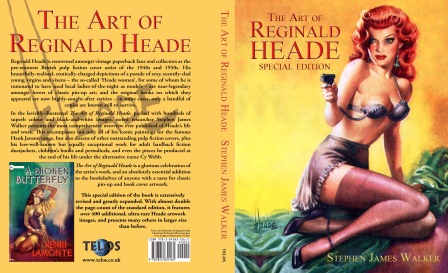

In the days before the covers of crime novels depended on typography, montages of stock photographs or pictures of females walking away into the distance – or to put it another way, in the days BC (Before Computers) – dust jacket design and art was a noble and very professional calling. Readers of recent columns (we know there are some) will have seen mentions of jacket designers and illustrators such as Tom Adams (Agatha Christie and Eric Ambler paperbacks) and Philip Youngman Carter (Margery Allingham and around 2,000 other titles) and in the past I have highlighted Richard Chopping (Ian Fleming), James Broome-Lynne (Dick Francis and Adam Diment), Raymond Hawkey (James Bond paperbacks and Len Deighton) and indeed Len Deighton himself.

Back in the 1940s and ’50s, in the heyday of British ‘pulp’ fiction publishing, covers were, shall we say, somewhat less restrained or indeed subtle, though undoubtedly many hours of concentration and perspiration in front of the artists’ easels went into them. One of the most famous, and I suspect widely imitated, cover artists was Reginald Heade, the pen-name (should that be brush-name?) of Reginald Cyril Webb (1901-1957).

To celebrate the work of ‘Heade’, which was how he signed many of his illustrations, The Art of Reginald Heade by Stephen James Walker was published by Telos Books in 2016 and a special extended edition came out in 2018. I now learn that those energetic and innovative people at Telos Books are planning a follow-up second volume, co-authored by Stephen James Walker and Steve Chibnall, to be published in August this year.

.jpg)

It is ironic, or perhaps poetic justice, that Heade’s cover art has survived and is celebrated long after the novels they adorned have been forgotten. An example, purely at random, would be Lady, Your Gun’s Showing by Timothy Trenton. Now I am pretty sure Timothy Trenton was an in-house pen-name used by the publisher, whoever it was, when in need of a story to fill a printing schedule as I can find no trace of him other than that he was also the author of Some Dames Die Quick in 1952, which also had a Heade cover. Another lost classic. (Sigh!)

Talking Pictures – What Next?

Ever since I discovered some of the Ripster Hall staff watching it on the 12-inch black-and-white television I allow in the under-butler’s pantry, I have become a devotee of Talking Pictures which can be found on Channel 81 (who knew there were more than four?) and is dedicated to old films and television programmes. And I do mean old, some of them almost as old as I am.

Apart from some fascinating documentary shorts showing life in Britain, especially London, in the 1940s and 1950s (when it was compulsory for everyone over the age of ten to smoke or work in a fish or flower market), the Channel specialises in old, mostly British, films which have not been seen on television for some time, and not at all by me.

One such, in January, was the 1952 film Venetian Bird from the novel and script by Victor Canning (1911-86), who was one of the leading thriller writers of the day. Several of Canning’s books were filmed, most famously one by Alfred Hitchcock, and he wrote widely for television, but his novels are sadly neglected these days.

Being an enthusiast for Venice as well as Victor Canning, I was keen to see how the film had turned out and, frankly, feared the worst. I was pleasantly surprised in that the film not only followed the plot of the book, but also had spent some time (and money) filming on location and it was delightful to recognise bits of Venice and not just the tourist sights, as they were in 1952 when everything was in black-and-white. True, there were repetitions of crowd scenes and some clumsy studio-shot interiors as the action moved briefly to the island of Murano but Richard Todd made a fair fist of the upright and slightly uptight British private eye who gets dragged into a political assassination. (The film was also known in some markets as The Assassin.)

My only qualm was with the casting of the minor characters, with stock British character actors such as John Gregson, George Coulouris, Sid James, Miles Malleson, Michael Balfour and Sydney Tafler all playing Italians, with cod accents ranging from the comical to the excruciating.

And if you recognise the names of any of those actors, then Talking Pictures is the channel for you.

|

|

Books of the Month

Back in 1999 I was one of many observers of the crime fiction scene who were disappointed, not to say outraged, that River of Darkness by Rennie Airth not only did not win the CWA’s Gold Dagger, but wasn’t even short-listed. It was Airth’s third novel, and his first for 18 years, and offered the unique combination of a 1920’s Home Counties set country house mystery with the hunt for a very scary serial killer by a police force which had no concept of a ‘serial’ killer. It was, and remains, an outstanding crime novel and is thankfully still in print, as are the subsequent adventures of its policeman hero John Madden, which have covered the period of WWII and beyond.

Fans of Airth’s thrillers are used to their sporadic appearance, but few could have expected two to come along at once.

Readers in the UK will welcome his stand alone thriller Cold Kill, published by Severn House, which is set in an unusually snowbound London (I personally don’t remember a time when snow was allowed to settle in Knightsbridge) and concerns a young American woman thrown in at the deep end of a conspiracy to steal the odd billion from Russian gangsters (who have stolen several billion). As well as our young heroine, some seriously violent characters are also after the loot and a very violent hitman is after them. Characters come and go with frightening speed and I mean ‘go’ in the Game of Thrones sense, as the body count is remarkably high even before the melodramatic finale at the Globe Theatre.

Cold Kill may require a hefty suspension of disbelief on occasion, but it will be generously given by the reader willing to be swept along by the sheer pace of the story-telling and the large number of plot shocks delivered along the way.

I am delighted to report, though I know nothing about it, that there also seems to be a new John Madden novel out, The Decent Inn of Death, though I believe this to be only in America.

The award-winning Australian writer Peter Temple (1946-2018) was one of the leading lights of crime fiction, known for his too-short series featuring Jack Irish, stand-alone novels, screenplays and journalism. In The Red Hand, now published by Riverrun, we get samples of all of Temple’s aforementioned skills and a tantalising hint of another one not included. In an introduction by his Australian publisher Michael Heyward, Temple is described as ‘a charismatic curmudgeon’ who had a penchant for sending caustically funny emails. Sadly we are only given a glimpse of these, but the ones from author to publisher which mention ‘Orange’, supposedly Temple’s literary agent – Agent Orange, geddit?- are hilarious.

This collection of short stories, an unfinished Jack Irish novel, reviews and essays, is a cornucopia of delights showing a fertile mind and a dry wit which is nowhere better on show that in his reviews of crime fiction. Here he ranges from Sherlock Holmes to Hannibal Lecter with observations which may not endear him to fans of Conan Doyle or Thomas Harris, but which are logical and fair. He is far from kind, but again possibly fair, on the work of John Le Carré and Kathy Reichs, and rather too generous to James Lee Burke, but he reserves his spleen for James Ellroy’s The Cold Six Thousand, which gets a good kicking. One wonders, with trepidation, what he would have made of Ellroy’s more recent work.

Reading Harry Dolan’s The Good Killer (Head of Zeus), I felt the same frisson as when, many years ago, I read my first Elmore Leonard. Here was a contemporary American crime novel pared of pretentions (no diversions into Catholic guilt, extended Irish immigrant families, lapsed alcoholics or lectures on baseball) which had good guys and bad guys all using violence to serve their ends or commit their crimes without a thought for the consequences except where they may incur more violence. Everyone who carries a gun in this gripping thriller shoots someone or gets shot and indeed the plot kicks off with a random ‘spree’ shooting by a crazed gunman in a shopping mall in Texas. It should say something about the availability of guns in America, but it probably won’t.

I was so impressed with the fluent pacing of the narrative, the twisty plotting (which involves theft, revenge, flight and pursuit across half America) and clearly but swiftly drawn characters, wonderfully displayed in a scene where the hero talks his way out of being arrested by a patrolling policeman, that I assumed The Good Killer was an exceptional debut novel, simply because I could not believe I had never come across Harry Dolan before. To my surprise, I discover that he has been writing crime fiction since 2008 although his output has been relatively small. I am assuming Mr Dolan has concentrated on quality not quantity and I intend to check out his backlist just to be sure. I will certainly be on the lookout for his next.

It is, incredibly, forty-two years now since Susan Isaacs’ debut novel Compromising Positions caused quite a stir here in the UK with striking covers for both the hardback in 1978 and the paperback in 1979. I remember them and the impact they had here – I believe the American covers were more restrained – and thinking at the time: was this really a book about the murder of a suburban dentist?

Susan Isaacs, however, proved that life (and death) in the suburbs was no laughing matter, by showing that it actually could be a laughing matter, and in Takes One To Know One (Grove Press) she does it again. Her heroine this time is a former FBI special agent now married and living in, of course, the suburbs working as a freelancer for three literary agents, even though sticking with the FBI might have been safer, especially given the book’s long and gruelling climactic struggle as she frees herself from a violent abductor.

I have never been a great fan of legal thrillers (nothing to do with the writing, just an aversion to lawyers), but I found Graham Moore’s new novel The Holdout (Orion) more gripping than those ubiquitous plastic restraints which have replaced handcuffs in crime fiction. This is probably because my own service on (and being foreman of) a jury many years ago was a supremely frustrating experience, but that is a story the world is not yet ready for.

In The Holdout Graham Moore, who wrote the screenplay for The Imitation Game so he knows what he’s doing, references both 12 Angry Men and Agatha Christie, and the novel has a similar premise – a single juror in a murder trial holding out for a ‘not guilty’ verdict – and then a murder in a closed environment with a limited number of suspects, all former jurors.

The narrative flits between the trial and a reunion, for a television documentary, of the jurors ten years after. One of them, convinced the Not Guilty verdict was wrong, is murdered and the prime suspect is the ‘holdout’ juror who swung the jury away from its initial Guilty verdict. Prime suspect, but by no means the only one as the back stories of the jurors are revealed. Out on a million-dollar bail, our ‘holdout’ (now a lawyer) is given remarkable freedom by the police to go off and investigate not only the murder she is accused of, but reassess the Not Guilty verdict of the original trial.

It is convoluted, pacey and has a final twist which Dame Agatha herself would have been proud of.

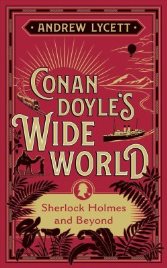

An absolute must for Sherlock Holmes fans, as well as devotees of good travel-writing, is Conan Doyle’s Wide World, published this month by Tauris Parke/Bloomsbury, which tracks the travels and writings of Arthur Conan Doyle from an Arctic adventure to Africa, South America to Switzerland (and a certain waterfall). Compiled and edited by Andrew Lycett, the bespoke biographer of Conan Doyle, Wilkie Collins and Ian Fleming among others, this marvellous collection contains extracts of Doyle’s writings and photographs not seen for some time, if at all before.

The fact that a new 50p piece honouring the Sherlock Holmes stories has just been put into circulation is, I am told, purely co-incidental.

It is terrible to admit, but the starting point of A Deadly Divide, a mass shooting at a mosque in Quebec sounds totally plausible these days. In her new novel, from award-winning publisher No Exit, Ausma Zehanat Khan, who was born in Britain but has lived in Canada and now the US), has her Canadian detective duo Khattak and Getty take on this high profile crime and uncover an electric web of community tensions.

A former human rights lawyer and editor of Muslim Girl magazine, Ausma Khan folds an all-too-topical storyline into a well-paced mystery plot and tackles serious political issues without ever preaching.

I had heard that Kensington had gone somewhat downhill in recent years but had no idea that the deprivation, drug-taking and prostitution had taken such a hold. Fortunately I quickly realised that Long Bright River by Liz Moore, now out from Hutchinson, is set in Kensington Avenue in Philadelphia.

To call it a police procedural is to do it a disservice, though it does centre on how the police deal with a drug problem of epidemic proportions and one policewoman searches for her lost sister; and to call it the story of a city, or a specific district of one, is to under-estimate it, for Long Bright River is really about a condition. It is long and densely written, eschewing punctuation marks and formal chapter breaks which may put certain readers off (ones as old as I am), but there is much to admire in the writing as it creates sympathetic and intimate characters from seemingly the skimpiest of raw material. Even in the squalor of life on those streets – and I am reminded of David Simon’s masterly Homicide set in Baltimore – one damaged character refers nobly to another as ‘not all bad, almost nobody is’.

Not technically a crime novel, but no doubt of great interest to fans of Scandinavian crime writers (some would say the Scandinavian crime writer), is The Rock Blaster, the debut novel of Henning Mankell (1948-2015), originally published in Sweden in 1973 and now in England by MacLehose Press.

It is, as one mighty expect, a grim, socially-realistic novel about a ‘blaster’ caught in a dynamite explosion in 1911 (losing a hand, an eye and other internal bits) who goes on working despite his crippling injuries until retirement and death in 1969. The novel charts not just his survival, but the impact on his life of social change (and injustice), the labour movement and his socialist ideals, the Hungarian uprising of 1956 and the threat of nuclear war. It’s gloomy and there are not a lot of laughs, but it provides a fascinating preview of the psychology of Kurt Wallander who was to become Mankell’s most famous creation.

Revival of the Month

I am delighted to hear that Severn House are to publish new editions (trade paperbacks and eBooks) of 21 Inspector Ghote novels by the late H.R.F. Keating, starting this month with A Small Case for Inspector Ghote and Inspector Ghote’s Good Crusade.

Harry Keating wrote about his self-effacing Bombay detective from 1964 to 2000, then took a break to develop a second series featuring Harriet Martens – as well as writing stand-alone novels, being crime fiction critic for The Times and President of The Detection Club – before returning to Ghote in 2008.

To mark Ghote’s return, I interviewed Harry in 2009 for Shots (https://bit.ly/2GCjOFql) and prophesied that there would be many more adventures for ‘the Mumbai Maigret’. Sadly, it was not to be and A Small Case for Inspector Ghote (it is, of course, anything but ‘small’) was his last appearance, but it is good to see him back.

Also, watch out for the biography H.R.F. Keating: A Life of Crime due in April.

Veganuary

A month ago I was asked by an inquisitive journalist if I intended to commit to ‘Veganuary’ which apparently is some sort of promotional ploy by the fruit and vegetable marketing board. My response was that as we would all be eating grass after Brexit, I was going out of my way to stress my carnivorous credentials.

But now that Brexit has been “done” – as have we all – I see no need to mention it ever again, for surely it has already dropped from public consciousness. One of the brighter ‘sunlit uplands’ promised, however, does mean that I no longer have to be nice about Scandinavian crime fiction and can read American mysteries under WTA rules.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|