|

Lockdown

Reading

Being a writer, I am used

to self-isolation. Being a reviewer, I am used to people crossing the street to

avoid me. Therefore the current lockdown promised little in the way of a change

to my routine, as long as my wine merchant was able to deliver (he was), except

that the number of new books getting through to me declined by an estimated 90%

due to under-staffed publishers and distributors and an over-loaded postal

system.

I was particularly

looking forward to John Lawton’s new novel Hammer To Fall from

Grove Atlantic, but for legal reasons this proved impossible.

So I have turned instead

to some notable non-fiction and a re-read of some trusty fictional favourites.

I was both educated and

entertained by Violet Moller’s The Map of Knowledge, now out in

paperback from Picador. This is basically the story of how classical ideas of

learning (i.e. books), on mathematics, astronomy and medicine, went from

antiquity to the Middle Ages and were rediscovered in the Renaissance thanks to

Greek, Arabic and Christian scholars and translators working in seven cities

from Alexandria to Baghdad, Cordoba to Toledo, Salerno to Palermo and finally

Venice over a period of almost a thousand years. If this sounds dry and boring,

it isn’t. It is a combination of intellectual travel writing and history,

packed with insight and reminiscent of Jan Morris’ outstanding books on Venice

for sheer readability.

I first read If Not

Now, When? by Italian Holocaust survivor Primo Levi about thirty years

ago, not long after his tragic death in Turin, which at the time was put down,

controversially, to suicide but is now thought to have been accidental. The

title of this episodic novel comes from ‘The Song of the (Jewish) Partisans’ of

Byelorussia during WWII and relates, loosely, the struggle of one band to get

out of Nazi-occupied Russia and into

(and then out of) Poland to an uplifting arrival, for some, in Italy at the end

of the war. It ought to be a grim struggle for survival, against the Nazis,

pro-Nazi Ukrainians, hunger and freezing winters, and it is but there is a

curious, noble optimism about the partisans’ odyssey. These are not heroes and

certainly not professional soldiers, but ordinary human beings coping with

unimaginable horrors. An outstanding novel by an outstanding writer of

non-fiction and surely somebody must have suggested before now that Steven

Spielberg ought to film it.

For another WWII story,

but this time a no-frills, action-adventure thriller, I returned to Colin

Forbes’ The Heights of Zervos from 1970, which is set over a

hectic few days in 1941 as a crack commando unit attempts to deny the invading

German army the key observation point of a monastery on top of a Greek

mountain. Colin Forbes, the pen-name of Raymond Sawkins (1923-2006), is perhaps

best known today for his spy stories featuring spy boss ‘Tweed’ but his early

success came, as with Alistair MacLean with war stories inspired in part by

personal wartime experiences. In Forbes’ case, both The Heights of Zervos

and The Palermo Ambush were straight out of the MacLean

playbook: a small number of unconventional military men on a crazy mission

against impossible odds succeeding on sheer guts, cunning and absolutely no sex

to slow down the action, all the action confined to timed periods within two or

three days to heighten the tension.

And then for something

completely different to revitalise those brain cells which I mothballed after

university, Jean Gimpel’s The Medieval Machine, which I believe

has been out of print since 1992. Gimpel, by no means an orthodox economic

historian, advances the theory that first industrial revolution took place not among coal fields and with

steam power in the 18th century, but with the technological

innovations made in Europe between the 12th and 14th

centuries in agriculture, water power, engineering and the invention of the

mechanical clock. (Okay, so the Chinese probably got there first on that one.)

If nothing else this energetic piece of revisionist history will answer the

sceptic who scoffed at John Turturro’s character (called Baskerville) in the recent TV film of The Name of the

Rose constantly searching for his ‘spectacles’. In a sermon in 1306, a

Dominican friar from Pisa gave a sermon of thanks in Florence for their

invention ‘not twenty years since’. This book overflows with such nuggets.

A

Life in Crime (Fiction)

I have neither trusted, nor

believed, any crime writer who claims to ‘never look at reviews’. I was

therefore delighted to discover that H.R. F. (Harry) Keating had kept newspaper

clippings of all of his going back over a crime writing career spanning half a

century, often tucked inside the jacket of the book being reviewed.

Harry Keating (1926-2011)

was a highly respected authority on, and practitioner of, crime fiction and

now, from Level Best Books, comes his long-awaited biography H.R.F.

Keating A Life of Crime, by Sheila Mitchell who married Harry in 1953,

and therefore is perfectly placed to provide some private insights into the

life of a working sub-editor on national newspapers and then crime writer.

I was interested to

discover that Harry insisted on total domestic silence when writing and loved

the image of him, in the 1950s, terrorising other road users as he zoomed

around in a Bond Minicar three-wheeler.(I’ll bet it was bright red, they

usually were.)

But Harry was a man of

books, not cars (and certainly not computers or the internet) and Sheila

Mitchell painstakingly lists the glowing reviews he received over the years, an

amazing number from fellow crime-writers including Anthony Boucher, Julian

Symons, Edmund Crispin, Anthony Price,

Reginald Hill, James Melville, Joan Smith and, I add humbly, even myself.

Most of those reviews

were for the novels featuring his most famous creation, Inspector Ghote, the

Maigret of Mumbai, and the famous story is retold of how Harry had been writing

about India and an Indian police detective for ten years before he first went

to the country, courtesy of a surprise invitation from Air India. It is Len

Deighton, however, in his introduction to A Life of Crime, who divulges the secret that Harry couldn’t

stand Indian food.

As if his award-winning

crime novels were not enough, Harry was a thoughtful and perceptive commentator

on crime fiction. If one thing is lacking from this affectionate biography, it

is not what the critics thought of Harry’s work, but what Harry thought of the

many books he reviewed for The Times over a number of years as their

crime fiction critic. Those reviews, pithy and exact, were quoted on hundreds

of paperbacks and were, for me at least, a fingerpost directing the reader to

good writing and sound plotting.

I have some personal experience of Harry’s

breadth of knowledge of crime fiction, as we co-operated to produce a list of

the best 100 crime novels of the 20th century for The Times in 2000.

(Our list can currently be seen on the CrimeFest website)

I still refer to several of the excellent

reference books written or edited by Harry, especially the wonderful Whodunit?

from 1982 and I had the good fortune to appear on several panels with him at

conventions and festivals over the years. I also, from the back stalls, saw

Harry’s bravest public performance when he was delegated to interview a

well-known American female crime-writer in a 250-seater auditorium in London.

Unfortunately, the crime-writer in question was not as big a draw as she

thought she was and seeing only 13 people in the audience (12 after I left),

she decided not to co-operate with the interview and remained sullen and

unresponsive throughout. Professional as ever, Harry carried on with gritted

teeth for the required hour, remaining totally polite and seemingly interested

in the career of his interviewee. For that performance alone, he deserved a

medal.

More Biog

It

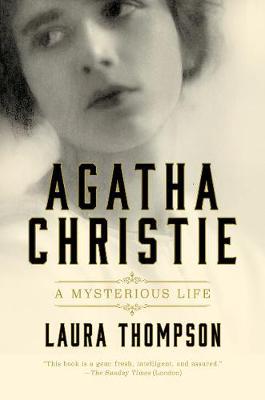

is shaping up to be a good year for biographies of crime writers as the recent

Keating biography appears alongside a revised edition of Laura Thompson’s Agatha

Christie – A Mysterious Life from Headline.

In a new Introduction to her book, first published in

2007, Laura claims that in the intervening period, thanks to revisionist

television adaptations, Christie ‘has become cool’.

I

met Laura Thompson in 2008 when we were both guest lecturers at the annual

convention of the Dorothy L. Sayers Society at the University of Surrey and I

remember teasing her about her refusal to watch The Unicorn and the Wasp,

the classic Dr Who episode where the Doctor meets Agatha Christie. We

also had a friendly disagreement about the novel Passenger To Frankfurt,

which she liked but which I had found (and still do) incomprehensible, but I

also heartily recommended A Mysterious Life, and do so again.

The

light at the end of the lockdown tunnel has come in the invitation to a launch

party – in October – for The Reacher Guy, the authorised

biography of Lee Child by Heather Martin, to be published by Little,Brown. For

that reason alone I am liking the book

already.

Looking

even further into future sunlit uplands, I hear that Steve Powell of Liverpool

University, has been commissioned by Bloomsbury to write the biography of that

‘demon dog of American crime writing’ James Ellroy (Ellroy’s words, not Steve’s)

with a view to publication in 2022.

Boris

I mentioned recently that

I recalled an article by Boris Johnson when he was a lowly journalist rather

than a prime minister which expressed his views on Scandinavian crime fiction.

Thanks to the wonders of the jolly old interweb, I learn that the article

appeared in that once great newspaper the Daily Telegraph on the 18th

January 2010.

Boris’ basic thesis to

explain the popularity of Scandinavian crime fiction is that we perceive that ‘Scandinavians

leave us standing in virtually every relevant category…Danes are rated the

happiest and least corrupt people in the world, closely followed by Sweden…

Iceland and Norway are the leaders in maintaining a free press, and Denmark,

Sweden and Finland have some of the world’s most open and competitive economies.

Let’s face it, folks, these countries are global goody-goodies. With their

historic (and unspoken) aversion to immigration they boast considerable social

cohesion, extraordinary literacy rates, beautiful and emancipated women and

such an effective health and safety culture that their cars must drive with

headlights on in broad daylight in the middle of summer.’

So far, so Boris, but he

concludes that because we cynical Brits

have been drip-fed this image of a superior Scandinavian life-style, we are

intrigued and ‘thrilled to discover that the whole place is in fact a whited

sepulchre of organ trading, prostitution rings, child murder and all the rest

of it’.

So is it a case of

British schadenfreude? Or, as the late, great Gore Vidal might have put

it: When I hear of a Scandinavian failure, my heart sings.

|

|

Screen Gems

The self-isolation edict is probably the reason I missed reports of the death of American actress Dyanne Thorne, at the age of 83, in January. Who? You may well ask. I did.

I am reminded, by a correspondent in South America, that she was the star, in the 1970s, of several films in what I believe is called the ‘exploitation’ school, most notably as the eponymous ‘Ilsa’ in Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS and then, after a spot of time travel: Ilsa, The Tigress of Siberia.

I have never seen either of these films – surely I would have remembered – possibly because the censors here refused to give them a certificate, for their gratuitous torture scenes, for which we should be grateful. I am, however, intrigued to discover that in later life Dyanne Thorne became an ordained minister of religion – in Las Vegas, of course.

Eurocops

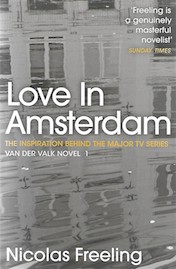

I cannot remember ever seeing the original television series of Van Der Valk even though it ran, off and on, for twenty years. It was, however, impossible to avoid the orchestral ear-worm that was its theme tune ‘Eye Level’, which turns up occasionally on select retrospectives of Top of the Pops, i.e. the ones without Jimmy Savile.

However, I was tempted to watch the recent remake starring Marc Warren and to welcome the new edition of Love in Amsterdam by Nicholas Freeling, the original source material, now published in Orion’s The Murder Room imprint.

I had not realised that Freeling’s first novel first appeared as long ago as 1962. Whilst there were undoubtedly examples before that, for me, his Van der Valk novels and their Amsterdam setting, marked the start of a trend, which continues to this day, of British crime writers creating European policemen protagonists.

Nicholas Freeling (1927-2003), who lived most of his life outside England, created two. After killing off Van der Valk (Spoiler Alert!), Freeling created a French detective, Henri Castang; and then there was Roderic Jeffries’ Inspector Alvarez (Mallorca), David Serafin’s Superintendent Bernal (Spain), Magdalene Nabb’s Marshal Guernaccia (Florence) and Michael Dibdin’s Inspector Zen, who covered most parts of Italy. Although never one to stick to a series, the late Julian Rathbone also experimented with numerous ‘Eurocops’.

In those far off days in the last century, such authors gave us an insight into life (and death) across the Channel when there was relatively little European crime fiction available here in translation. There was Simenon of course, a few Jean Bruce novels for thriller fans, left-leaning police procedurals from Sjöwall & Wahlöö and then later, in the early 1990s, the gritty Parisian tales of Leo Malet, but little else. At least that’s how I remember it through rose-tinted glasses, all the time thinking: if only there was some sort of club or ‘union’ of European countries we could be a member of …

A Tripp down memory lane

I have known for many years that ‘John Michael Brett’, the creator, in 1964, of man-about-danger Hugo Baron, was the pen-name used by crime-writer Miles Tripp (1923-2000) for his short series of thrillers clearly aimed at the booming James Bond market following the release of Dr No.

I am sure I must have read, perhaps even reviewed, some of his later detective stories but I have only recently started to catch up on the thrillers he wrote under his own name. The Claws of God, first published in 1972, is a taut, suspenseful tale set in Egypt in the 1960s, of an ill-fated ‘tourist trip’ into the desert beyond Cairo. The reason for the trip (no pun intended) eventually becomes clear and violence follows, but at the heart of the book is a wonderful character study of an unheroic hero, Oliver Pugh, a listless, fly-blown ex-pat RAF officer who had spent WWII in Egypt and who had neither the imagination nor drive to find a life outside the routine he had created for himself there.

Miles Tripp himself served in the RAF in the Middle East during the war and must have known that character type and his description of Pugh is spot-on, sympathetic and often funny, but without being cruel.

Books

of the Month

A limited selection this

month, as both book distribution warehouses and the post office have both been

affected by shortages of staff for sadly obvious reasons.

The horrific mass shooting

of young people perpetrated by right-wing nut-job Anders Breivik in 2011 rocked

Norway and shocked the world. Clearly inspired by such a horrific event (if

‘inspired’ is anywhere near the correct word in this context), Ben McPherson, a

Brit who now lives in Oslo, makes a mass-shooting both the opening and core of The

Island, out now from HarperCollins.

The protagonist, Cal Curtis, is a foreigner, married to a Norwegian and

raising a growing family in Norway. When his eldest daughter is assumed to be one

of the victims of the recent mass-killing, but then it appears she wasn’t, both

his wife and younger daughter begin to act in distinctly odd ways and Cal

realises he is an outsider in more ways than one.

The Island is

a totally gripping suspense thriller and the fact that you know something like

the opening section not only could, but has, happened in a prosperous,

peace-loving country like Norway, simply adds to the dramatic impact.

What better way to celebrate

a 75th anniversary than with an anthology of crime stories each

featuring an anniversary? That could, I admit, sound a rather contrite and

contrived excuse for an anthology but when the 75th anniversary in

question is that of the Mystery Writers of America, and all the

contributors to it are past presidents, Grand Masters or MWA award-winners,

then the real crime fiction fan ought to sit up and take notice.

Deadly

Anniversaries, edited by Marcia Muller and Bill

Pronzini, from Hanover Square Press, contains stories from some very familiar

names, including Lee Child, Sue Grafton, Jeffrey Deaver, Margaret Maron, Laura

Lippman, Peter Lovesey and Peter Robinson, as well as some who ought to be

better known on this side of the Atlantic, such as Carolyn Hart and Julie

Smith. And there are contributors whose acquaintance I look forward to making

for the first time, including Doug Allyn, Naomi Hirahara and Wendy Hornsby.

And speaking of

anthologies, one arrived too late to be read closely, or indeed at all, but as Broken,

from HarperCollins, is a collection of six short novels (novellas?) by American

maestro Don Winslow, need I say more?

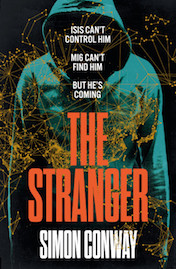

Those who like a traditional ‘thick-eared’ thriller – and I

don’t mean that in a pejorative sense as I like a bit of thick-eared escapism

now and then – need look no further than the new novel from Simon Conway,

published by Hodder.

The Stranger features

an MI6 agent (and perhaps gigolo) who seems attractive to all the women he meets

and the plot, at first, centres on the hunt for a suspected terrorist called

The Engineer, who was subjected to rendition ten years ago and has only

recently been broken out of a Syrian prison. But The Engineer is not The

Stranger of the title. He is a far more dangerous terrorist who comes out of

hiding to conduct a private war of revenge against…well, that’s the mystery

(unless you twig the clue when his real name is revealed). The action is fast

and furious though it does require a suspension bridge of disbelief to accept

how, after ten years in an Isis cave, The Stranger can suddenly call on vast

resources of cash, false documentation, the devotion of numerous suicide

bombers, a female assistant with a very odd take on love-making and, once in

Britain, a huge arsenal of ordnance needed to deliver the frighteningly high

body count. (One assumes he kept up with all the updates for Microsoft 10).

There are times when the

‘tradecraft’ reminds me of Day of the Jackal and others where the plot line echoes

that of Skyfall, and our MI6 hero has, as all good 1960s sub-Bondian

heroes had, his own personal expertise in ‘the ancient martial art of pencak

silat’.(No, me neither but it comes from Indonesia apparently.) I did love Conway’s description of a posh

Berkshire village as the ideal retirement home for ‘Whitehall mandarins and espiocrats’

– a term I had not come across before, but which I will purloin immediately.

Missing

in Action

There were several books

I was looking forward to seeing in May but have so far failed to set eyes on.

These include Double Agent by Tom Bradby, The Less Dead by Denise Mina and The

Sandpit by Nicholas Shakespeare, to name but three. This I am sure is

not due to legal reasons, but down to self-isolation and reduced working in the

publishing trade, at least I hope so. It may be that their dates of publication

have been book back to later in the year, as has already happened with several

forthcoming titles.

Lockdown Blues

Whilst the death toll from Covid 19 is, of course, awful – and in April included my old chum, thriller writer Alan Williams – I am constantly bemused by the complaints of those, mostly urbanites, who can ‘think of nothing to do’ during self-isolation in their homes. And then I am comforted by the large number of messages I get from fellow writers who say I’m sitting in front of a keyboard drinking too much and not talking to anyone, so no change there then.

The only consolation to be taken from this horrid situation is that Norwich City have stayed in the Premier League far longer than anyone thought they would.

Stay safe, stay well

and keep your distance,

and as they say in Italy,

‘Andra tutto bene’.

The Ripster.

|