Lockdown Discoveries

In July the Covid-19 lockdown brought a peaceful respite with few new books being sent out for review and only minimal pestering by publicity assistants working from home as opposed to being at Wimbledon as they normally are. It was an opportunity to have a thorough Spring Clean and sort out of the contents of filing cabinets not opened for many a year.

I discovered something I had almost forgotten: the souvenir 500th edition of Red Herrings, the normally highly confidential monthly newsletter of the Crime Writers’ Association. The break with secrecy and the production of a special issue to mark its 500th edition (price £4) resulted in some excellent copy and some wonderful historic photographs, all smoothly edited by that erudite man-about-town Mr Peter Guttridge.

Published in 1998, it contained contributions from the leading crime writers of the day and a quiz set by me, celebrating (it seems) my ‘tenth anniversary as crime critic of The Telegraph’ (sic) and relying on my ‘encyclopaedic knowledge of crime fiction’.

I have honestly no memory of setting this quiz, which offered the prize of a ‘summer hamper of crime books’ and I am pretty sure I was never told if anyone had entered or won because I was not a member of the CWA and therefore not allowed to see the 501st edition of Red Herrings, which probably contained the answers and winner.

There was, however, much to relish in that souvenir edition, much, I admit, I did not fully appreciate at the time twenty-two years ago (perhaps I should have read it). There is, for instance, a lovely piece about ‘forgotten man’ Francis Clifford by the late Harry Keating, although I was well aware that Harry and I were both fans of Clifford’s writing. And then there’s Peter Lovesey’s contribution, fondly remembering international trips by the CWA to the USA and Sweden.

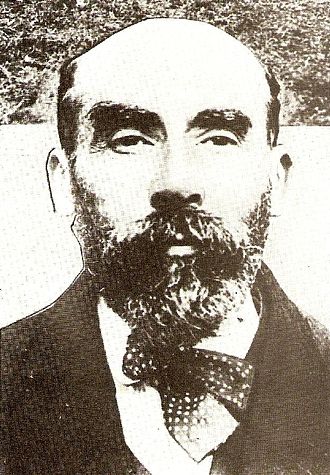

But best of all are the snippets of gossip about the CWA such as when, at a 1967 meeting held in London’s Chamber of Horrors museum, a television reporter covering the event spotted that Desmond Bagley was a dead ringer for Henri ‘Bluebeard’ Landru, the French serial killer guillotined in 1922.

} }

But the CWA’s earlier days in the 1950s provided some of the juiciest morsels. Founded by the prolific John Creasey, the CWA boasted 60 members in its first full year (1954) only for it to be discovered that twenty names on that membership list were pen-names used by John Creasey. (Yes, twenty. I told you he was prolific and tried, but failed, to limit his output to twelve books a year.)

Creasey also attempted to have critic (and crime writer) Julian Symons expelled for not being ‘positive’ enough about fellow members work. Symons himself is quoted as saying he found sitting next to Agatha Christie ‘a trial’ and for causing a stir when he chose Yes, we have no bananas as one of his Desert Island Discs.

There were some notable absences in the ranks in the first years of the CWA. Agatha Christie politely declined to join, as did Winston Graham, despite winning the first Red Herrings Award, the forerunner of the CWA’s ‘Daggers’. Dennis Wheatley was persuaded to join, but resigned almost immediately when a membership secretary spelt his name ‘Denis’ not once, but twice. Dorothy L. Sayers was thought too intimidating to be even asked if she would like to join, and there seems to have been no mention of Ian Fleming or Margery Allingham who were both very much on the scene in those formative years.

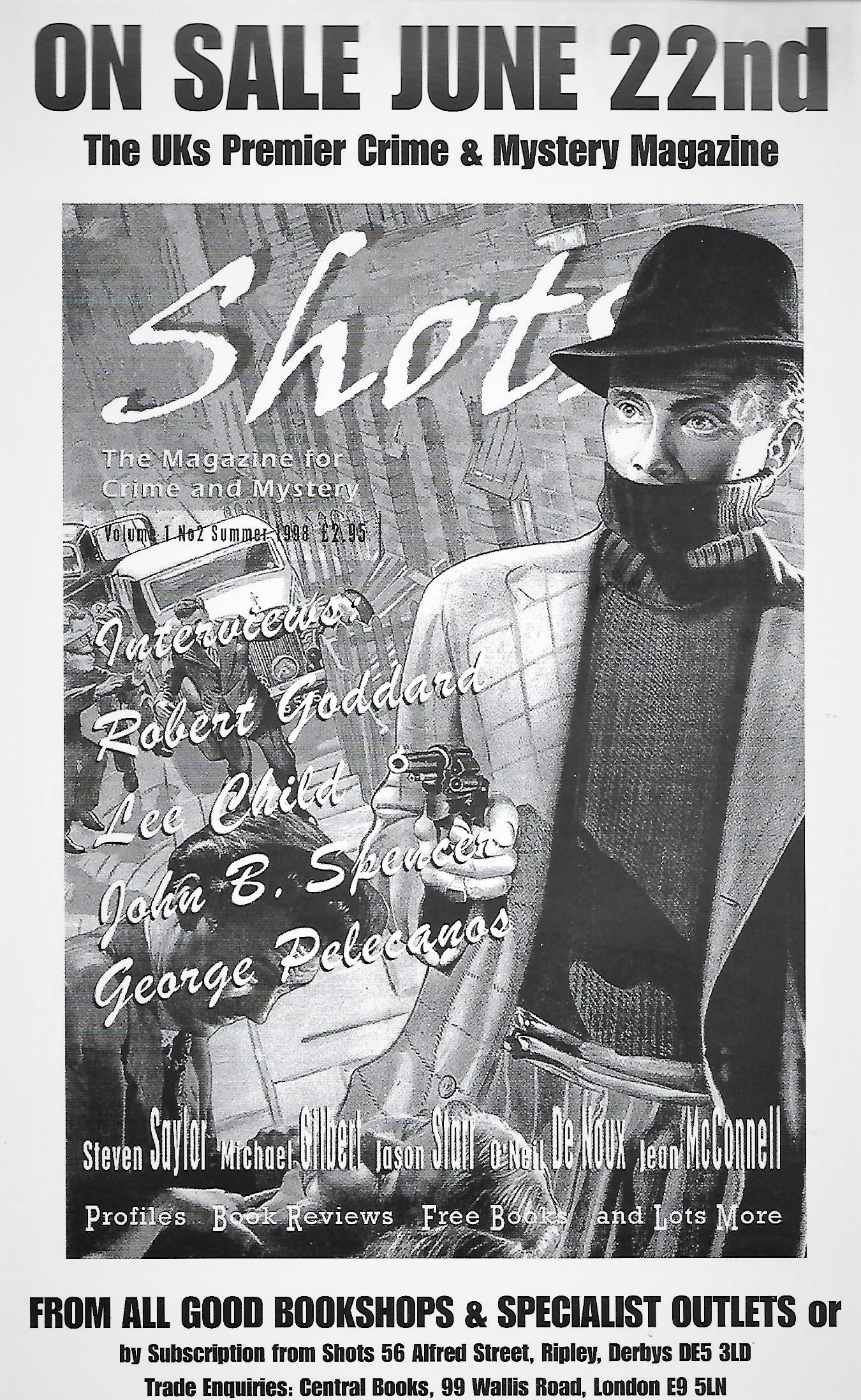

That 500th Edition ‘special’ of Red Herrings was also notable for an article by one Mike Stotter and a full-page advertisement announcing a new format for a magazine called Shots with a cover designed to appeal to the nostalgia felt for the early days of the CWA. What became of the magazine is anyone’s guess.

Red Herrings returned to being the private monthly house magazine of the CWA but after twenty-two years, it must surely now be on issue #750 or thereabouts, which would be a good excuse for another souvenir edition, perhaps revealing a few tasty morsels about life behind the scenes in, say the 1970s and 80s. I’d pay four quid for that.

*

And among other gems discovered in a dusty filing cabinet was the original typescript of my 1995 Dorothy L. Sayers Lecture. I was, I am pretty sure, the second crime writer to have the honour to deliver what is still an annual event, P.D. James (a hard act to follow) having given the inaugural lecture to the DLS Society.

Skimming through that lecture, my eye was caught by a slightly waspish aside concerning television adaptations of ‘Golden Age’ detective stories trying to compete with the success of Poirot, in particular those of Ngaio Marsh. I suggested that it had proved difficult to find an actor who can make Roderick Alleyn an interesting character. Simon Williams and Patrick Malahide have tried, as has George Baker, who wisely opted instead for Ruth Rendell’s Inspector Wexford.

As I was reading that twenty-five-year-old script, the wireless was repeating some demented monologues from a makeshift ‘lockdown’ edition of The Archers and I realised just how much I was missing hearing Simon Williams’ perfect diction in the role of Justin Elliott.

Lockdown Delays

The lockdown may be easing, but its effects will linger like a bad odour with many new crime and thriller titles already having suffered from the effects of disruption to the workings of publishers’ offices, bookshops, libraries and distribution warehouses. Some titles have (wisely) been re-scheduled, although not everyone was told about this…hence my review of one new thriller in May although the book is not available until later this month.

Some publishing date changes have been publicised. For example Steve Cavanagh’s new thriller Fifty Fifty which has been moved from July and will now be released in September by Orion.

I was also looking forward to Simon Scarrow’s move from ancient Rome to World War II in a thriller set in Nazi Germany, Blackout, from Headline, which was scheduled for this month but has been rescheduled for March 2021.

For legal or virus or postal reasons, or perhaps all three, I am unable to report on several books which had been firmly on my radar for August, including: Moonflower Murders by Anthony Horowitz, Arkhangel by James Brabazon and The Package by the bestselling German crime writer Sebastian Fitzek.

Every Day a School Day

I am constantly indebted those energetic Americans behind Stark House Press for introducing me to writers I was unaware of. The latest is Gil Brewer and Stark House have just produced one of their ‘double decker’ two-books-in-one volumes containing The Tease and Sin No More.

Gilbert Brewer (1921-1983) was, and I quote, ‘the author of dozens of wonderfully sleazy sex/crime adventure novels of the 1950s and ’60s’ possibly the most famous being Nude on Thin Ice.

Surfing the Interweb

As my regular pastime of lurking in second-hand bookshops has been curtailed this year, I have taken to trawling the jolly old interweb for hidden or forgotten gems. Although I was not tempted to purchase it, I did come across Criminals of Want, published (possibly self-published) in 1968, by Stephen Frances.

This is hailed as the first volume of a quartet of novels set during the Spanish Civil War, but what sparked my interest was the name of the author. I knew that Stephen D. Frances (1917-1989) had a long association with Spain and always thought it slightly odd that a left-leaning, avowed conscientious objector should be so happy to live there under the Franco regime.

Of more interest to crime fiction fans, or at least historians of the genre, is the fact that Stephen Frances was at one time one of the best known, nay notorious, names which adorned some of the most garish paperbacks covers of all times, or rather his far better known pen-name: Hank Janson.

And speaking of garish covers, though more tasteful ones, I am looking forward immensely to Cover Me, the vintage art of Pan Books 1950-1965 by Colin Larkin, which is expected in December this year.

{

As this is certain to contain the covers of many of the books in my paperback library (it had better!), this likely to be the ideal Christmas present for the crime fiction buff this year. It will be published by those enterprising and inventive chaps at Telos Publishing (www.telos.co.uk), who also, incidentally, publish several Hank Janson titles as well as many other notable (prize winning) crime novels. Just saying.

And still speaking of cover art, I have learned of a cover artist and jacket designer of whom I was previously unaware, thanks to the researches of Philip Eastwood (of The Bagley Brief website), aided, I am told, by Jamie Sturgeon, of JRS Books, one of my aforementioned favourite bookshops on Ebay.

Oliver Elmes (1934-2011) was an artist and graphic designer who is probably best known for his work with the BBC on the title sequences for, among others, The Good Life and Dr Who (the Sylvester McCoy incarnation). He was also a prolific designer of book jackets, notably for novelists John Harris and Simon Raven, but of particular interest to fans of vintage thrillers are the covers he did for Simon Harvester.

Simon Harvester was the pen-name of Henry St John Clair Rumbold-Gibbs (1909-1975) whose first book was published in 1942, but who establish his reputation as a thriller writer for his 1960s spy novels set in Central Asia and the Far East, which were noted for their local colour, detail and often shrewd predictions about power politics in in the region. Legend has it that the KGB station in Kuala Lumpur always placed a bulk order for copies of any new Harvester novel.

Twice is Coincidence

It may simply be happenstance if the publication of Stephen Clarke’s new novel in November coincides with the delayed release of the new James Bond film. For legal reasons – real ones this time – I will not speculate

The Spy Who Inspired Me does not actually mention Mr Bond, but is a comic thriller featuring a suave naval intelligence officer called Ian Lemming who is accidentally stranded in Nazi occupied Normandy in 1944. To escape capture, Lemming gets a crash course in spycraft from a female agent called (wait for it) Margaux Lynd, though I am unaware as to whether she takes him to the local casino. She is, however, inspirational and Lemming has a fertile imagination, so the outcome is inevitable.

This may sound like heresy to Bond fans, but you have to admire one thing about Stephen Clarke: after writing books entitled A Year in the Merde and 1000 Years of Annoying the French, he is still alive and prospering, living in Paris.

More Bodies

I am unsure what the appropriate collective noun for Golden Age detectives is, but a clutch of them crop up in Bodies From The Library 3 anthology edited by Tony Medawar and published by the famous Collins Crime Club.

The library in question is, of course, The British Library which (in happier days) served as my London office on very favourable ‘hot-desking’ terms.

The detectives in question include Hercule Poirot, Roger Sheringham (in a bit of patriotic wartime propaganda), M. Henri Bencolin, the aforementioned Roderick Alleyn, Nigel Strangeways and a Captain Mainwaring (no, not that one).

This third volume of “forgotten stories” contains may famous names from the ‘Golden Age’ (which is specifically defined as the years between 1913 and 1937) and beyond: Christie, Marsh, Anthony Berkeley, Dorothy L Sayers, Cyril Hare, John Dickson Carr, Ethel Lina White and, perhaps surprisingly, Peter Cheyney. There are one or two authors I was unfamiliar with along with mentions of two fictional detectives – the Rev. Ebenezer Buckle and Inspector Clutson – which allowed me my usual “Me neither” reaction.

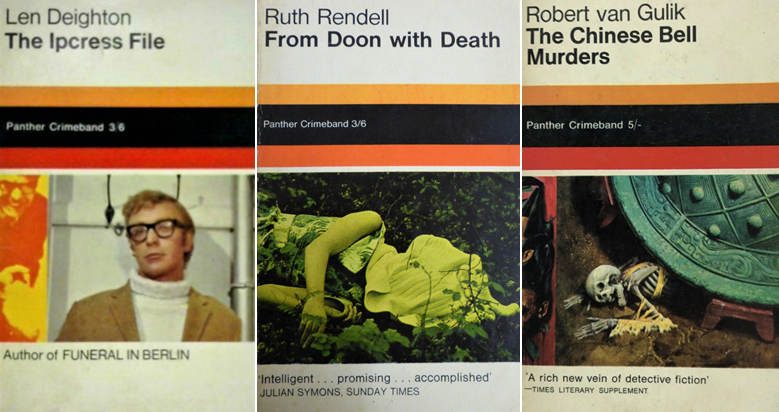

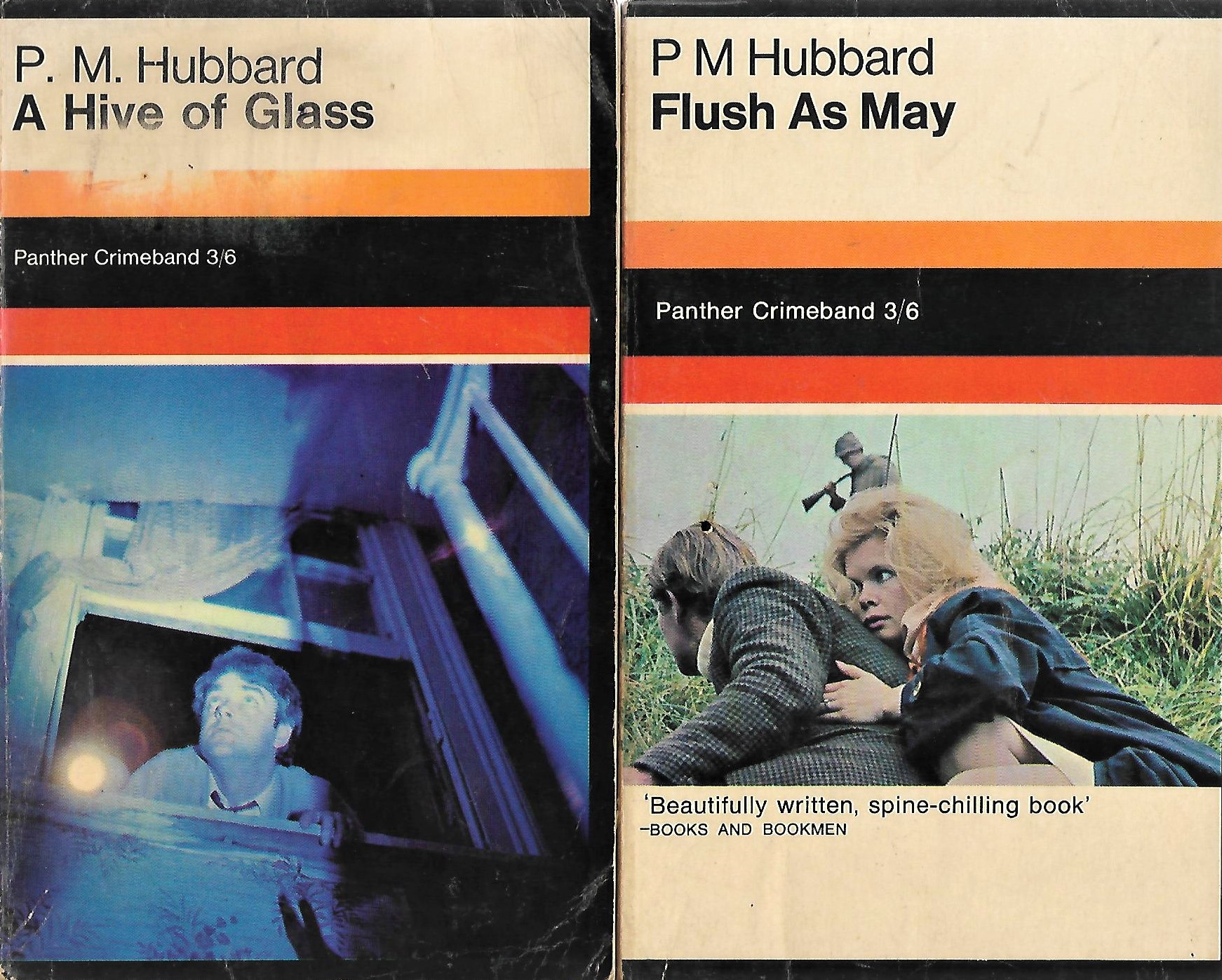

Tune to the Crimeband

In the days when you turned a dial to tune the wireless (‘Wireless, grandad?’) the paperback publisher Panther launched a crime imprint known as Panther Crimeband, the promotional idea being that readers could ‘tune in’ to good crime fiction by following the eye-catching ‘bandwidth’ branding on the cover.

As far as I can ascertain, only a handful of authors made it into Crimeband paperbacks in the imprint’s heyday between 1966 and 1968, but among them were some personal favourites, including Len Deighton, Ruth Rendell, Robert Van Gulik, John Blackburn and P.M. Hubbard.

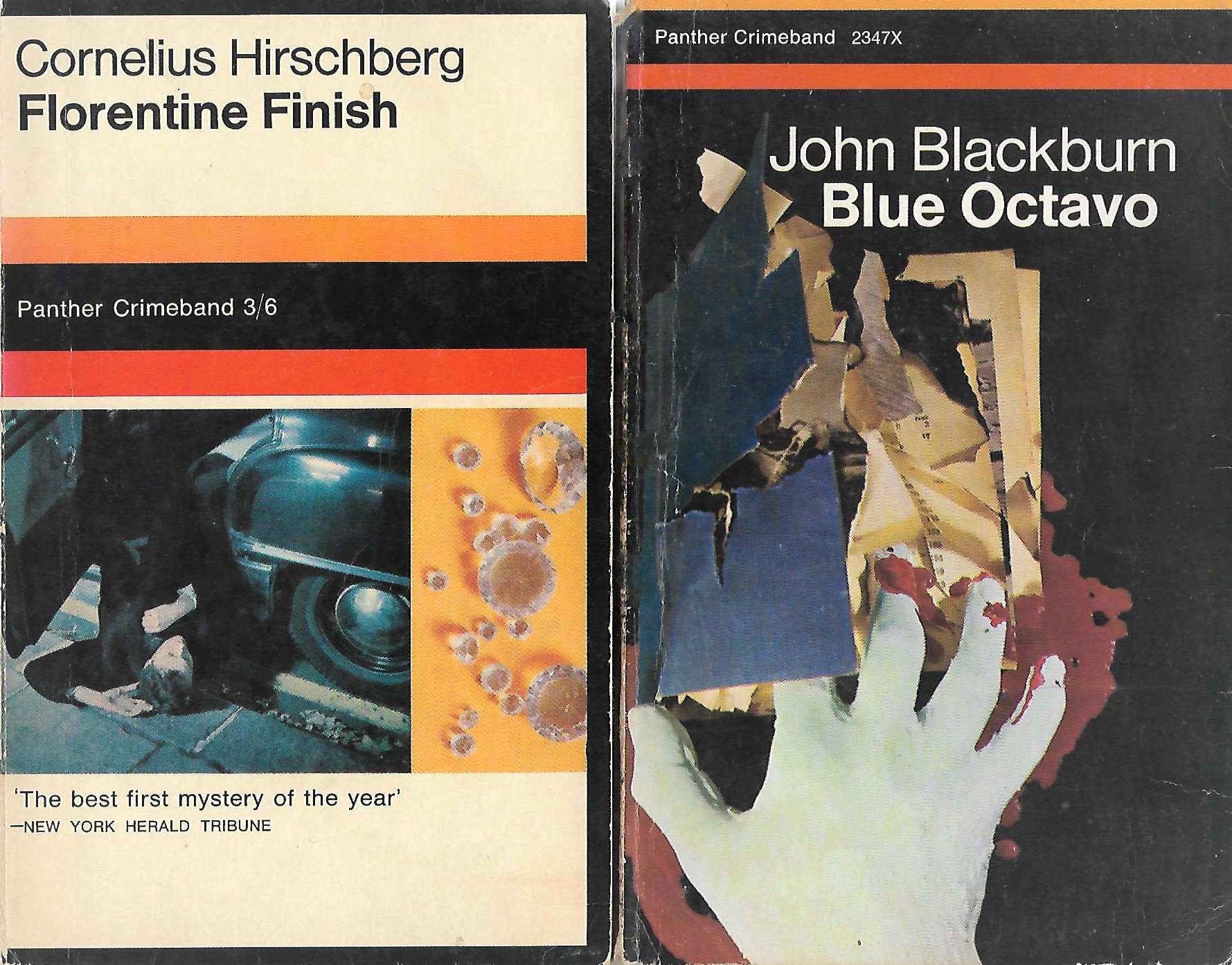

There was one author I was totally unfamiliar with, but his name, and the title of his Panther Crimeband, stuck with me over the decades until I spotted a copy for sale at last year’s Paperback and Pulp Fiction jamboree in London.

I still know very little about Cornelius Hirschberg and it could be that Florentine Finish was his only crime novel, but I remembered the book as a familiar sight in the bookshops I haunted in the second half of the 1960’s. Perhaps it was because it was one of the few Panther Crimebands which ‘got away’ from me. Certainly, I was unaware at the time that it had received a rave review from Francis Iles, the accolade ‘best crime novel of 1964’ and had won the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for best first novel.

It is a good, solid crime story set in the diamond and jewellery district of New York where an ex-cop turned diamond dealer is framed first for the theft of a diamond and then murder. There is a lot of detail about diamonds, their cuts, evaluation and appearance, all told in a downbeat, hard-boiled style, which suggests Hirschberg knew what he was writing about and his hero is a straight-up, honest sort of guy who rarely resorts to bad language. I mention this because on the few occasions he lets forth an exasperated ‘Good God!’, ‘God-dammit’ or ‘God knows’ and even a ‘Jesus!’, some enthusiastic previous owner of my copy has attempted to censor him.

That sensitive soul has tried to eradicate any and all uses of the words God and Jesus not by crossing out with pen or pencil but by trying to remove the words with a razor, and I don’t know about you, but anyone with strong religious opinions and a sharp blade makes me uneasy.

Panther Crimebands are now rare and the imprint seemingly not valued greatly, or even remembered, by collectors, which is a pity and surprising given some of the authors who appeared on their list, however briefly. Apart from Cornelius Hirshberg, one other Crimeband author eluded me, and still does: Jeremy Potter. At the time, Ronald Jeremy Potter (1922-1997) was writing conventional crime novels, which I did not realise when I first heard his name in connection with the Richard III Society, of which he became chairman and then president. In the 1970’s he was to establish a reputation with historical mysteries and it is for those he is best remembered.

I have identified a dozen Panther Crimeband titles (I am sure there must have been more) of which I read seven at the time (and still own four of them) and now, more than 50 years later, an eighth. I don’t think that’s a bad hit rate.

|

|

Books of the Month

(And possibly last month or maybe next month. Publishing dates and the distribution of review copies have been somewhat erratic of late, plus I have lost all sense of date and time.)

Still smarting from the enforced cancellation of a Spring Break in Bologna, it was ironic that three of my favourite reads this month have come from Italian authors and I strongly recommend all of them.

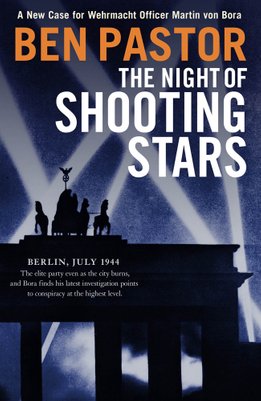

Ben Pastor’s series hero, Martin von Bora, and the late Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther are invariably linked, both being German protagonists operating in the Nazi era. But where Gunther is a left-leaning professional detective and occasional, reluctant, soldier, von Bora is an aristocrat and dedicated front-line soldier, an often reluctant detective and even more reluctant dispenser of justice.

The fictional von Bora is often compared to the real Claus von Stauffenberg, an aristocrat and Catholic mutilated in the war, and also a senior Wehrmacht officer. But there are important differences and nowhere better illustrated than in The Night of the Shooting Stars [Bitter Lemon Press] which is set in Berlin in the dozen or so frantic days before the 20th July 1944 and the ‘Stauffenberg bomb plot’ against Hitler. [Spoiler alert: it failed.]. There is even a crucial, and very dramatic scene between von Bora and von Stauffenberg where von Bora makes it clear he has no time for political coups (at that stage of the war) and simply wants to return to lead his troops on the Italian front. The fact that he is in Berlin at all is down to his reputation as in investigator, for while attending the funeral of his uncle (whose death may have been an officially sanctioned suicide) he is ordered to investigate the murder of an eccentric clairvoyant and stage magician from Weimar days.

It is not, as one might expect, a straightforward case, though if any reader remembers the original English title of Die rote Kimono, they should keep it to themselves, and once again Ben Pastor shows the depth of her research, from brands of cigarettes and army-issue condoms to ballistics and firearms – she is particularly good on small arms.

This is the seventh Martin von Bora novel to be published in the UK, though in fact it is actually the thirteenth on the series. Ben (Verbena) Pastor writes in English but her books are published first in Italy and, having bought La note delle stelle cadenti in Milan last year, I can say with confidence that she is brilliantly translated into Italian by Luigi Sanvito.

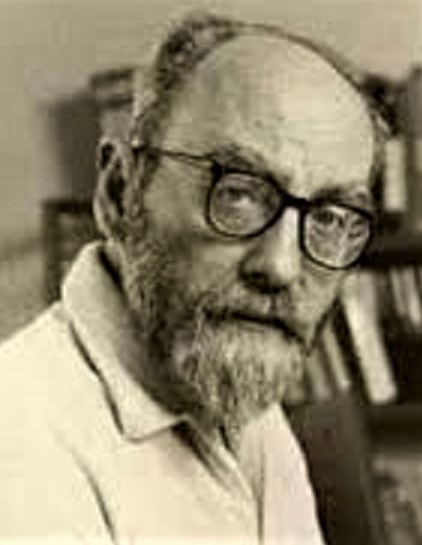

Ripster with his translator and Ben Pastor with hers

Ben Pastor’s Martin Bora books, which she has been writing since 2000, are a remarkable achievement. Not only is the background research which goes into them – involving settings from the Spanish Civil War, wartime Italy, France and Crete, to campaigns in the Ukraine and Russia – absolutely stunning, but so too is her grasp of the mentality of the professional solider following his own code of honour whilst doing his best to be a decent human being. For all his personal faults and weak spots (women in particular), and the fact that he is fighting for the most odious of regimes, Martin von Bora is a hero you want to cheer for.

This is superior, very intelligent, historical thriller fiction at its best.

I fondly remember a conversation with the late Marcel Berlins about Superintendent Teresa Battaglia, the Italian detective created by Ilaria Tuti, and agreeing that here was a character whose career was worth following. Now Teresa returns in a second thriller, Painted In Blood [Weidenfeld & Nicolson], set in Friuli, the top right-hand corner of Italy above Trieste, bordering Slovenia, where the author makes the most of the wild terrain of mountains, forests and hidden valleys, especially those spooky hidden valleys.

Teresa is an unusual heroine: over sixty, overweight, short-tempered and foul-mouthed, suffering from diabetes and the onset of Alzheimer’s, something she is desperately trying to hide from her colleagues. She suppresses a personal trauma from her past which dovetails into one of the several major themes of the book, and she is also described as having ‘an elective affinity with the dead’.

The mystery here centres on a painting, ‘The Sleeping Nymph’. dating from 1945 which is found to have been, literally, painted in blood, possibly the heart blood of the young female model. The artist, seventy years on, is still alive but in a vegetative state, not having spoken for decades, but obsessed with watching the forest across the valley. Identifying the girl in the painting and then the search for her remains involves Teresa Battaglia in a heady, sometimes hallucinatory, mix of graveyard excavations, pre-Christian shamanistic rituals, infighting within the police hierarchy, partisan activity during the Nazi occupation, a missing religious icon, possibly witchcraft and another murder by heart-removal. In this she is aided, and sometimes hindered, by her sidekick deputy Massimo Marini (who has his own tragic sub-plot) and a blind woman who has trained a dog to sniff out human remains. They, and all the minor characters, are fully realised and well- drawn and the whole thing comes to a frantic (perhaps a little too frantic), almost mystical conclusion.

Painted In Blood shows a young writer flexing her muscles trying, and succeeding, to produce a crime novel which is distinctive, unusual and makes full use of the myths and magic of its chosen landscape.

Maurizio Di Giovanni’s early crime novels were atmospheric, rather spooky (and also rather good) historical mysteries set in Mussolini’s fascist Italy, specifically the Naples of the 1930s. His current series is set in modern Naples, mostly in the district of Pizzofalcone and around a beleaguered police station there which may come to be known as the Italian 87th Precinct.

Puppies (For the Bastards of Pizzofalcone) [Europa Editions] does indeed feature a lost puppy dog, but that’s not the main focus of the book, which opens with the discovery of a baby abandoned next to a dumpster near the Pizzofalcone station, and the subsequent search for (and awful discovery of) the child’s mother among the substantial population of illegal immigrants from Ukraine and Romania.

When I met Maurizio Di Giovanni some years ago, he had just embarked on his new series of ensemble-cast police procedurals, which have now been successfully adapted for Italian television. He explained to me that the Pizzofalcone district of Naples fascinated him, not because it was such an ancient part of the city, but because in the contemporary, rebuilt city its borders touch on areas of old working-class poverty as well as new middle-class prosperity, making it a crossroads of values, morals, religious belief and, of course, crime and corruption. The criminal element is nowhere better illustrated than by the Pizzofalcone police station itself. Once so corrupt was it that it was in danger of being closed down and the cops now posted there do not see it as a promotion, hence their nickname of i bastardi.

Most, possibly all, of Maurizio’s fiction is set in his beloved Naples (where he is a fanatical supporter of the local football team) and I asked him if it was true that Naples was in a way, in a different country to the rest of Italy. ‘No,’ he said forcefully, ‘it’s on a different planet.’

Pizzofalcone is well worth a visit, particularly for anyone who enjoyed the work of Ed McBain and Joseph Wambaugh (and, it could be argued, the Resnick novels by John Harvey in this country), as Di Giovanni is in that sort of company.

My find of the month, if not the year, is S.A. Crosby’s debut novel Blacktop Wasteland [Headline], a turbo-charged heist thriller centred on a professional getaway driver, some amateur thieves and some very scary gangsters who rule the roost in rural southern Virginia. This is not an environmentally-friendly thriller as much of the action involves vehicles burning up the ‘blacktop’ highways (or, indeed, just burning) with enough super-charged detail to satisfy the most ardent petrol head.

British readers may also be slightly disconcerted to discover that two of the ‘poor white trash’ thieves featured (they don’t mind being white trash, but they hate being poor) are brothers called Ronnie and Reggie…

But get over that, strap in and enjoy a screaming wild ride through the best slice of hardboiled American noir published this year. There are plenty of good one-liners along the way and, in Chapter Eight, a world-class one; and if Shawn Crosby’s narrative voice doesn’t quite yet match that of Elmore Leonard, it’s getting there.

Just how many unreliable narrators can you squeeze into a crime novel? Simon Lelic goes for at least four (not a spoiler alert) in The Search Party [Viking] where a group of young teenagers go, as if channelling Stephen King, into the dark, dark woods to hunt for a missing girl friend, presumed dead by the police although they have conspicuously failed to find a body. The official investigation is hampered by a bullying senior policeman more worried about budgets and public relations than finding the missing girl and the copper in charge of the search, which takes place in his home town, who has to face the bad memories it holds for him.

When the unofficial search party sets out, they quickly run out of food and water and – worst of all – have their mobile phones stolen. Clearly there is a psychopath lurking in the woods, if not (as one of them is convinced), a bear and from the way the group rapidly disintegrates, you’d think this was up country Cambodia and not the wooded estuary of a seaside town (on the south coast?).

Simon Lelic leads his readers into this particular heart of darkness by the nose, throwing in plot-twists and mis-directions at every opportunity. A careful reader keeping count can spot one very important clue and the cynical reader familiar with this sub-genre of mystery will spot (by default) the murderer very early on, but those happy to go along for the ride – and why not? – will suspend disbelief and be delighted to let Simon Lelic bamboozle them.

As my familiarity with mathematics has never gone beyond trying, and failing, to understand a publisher’s royalty statement, I will certainly have missed many a subtle pointer and/or clue in Alex Pavesi’s Eight Detectives [Michael Joseph] which plays with, and occasionally subverts, the conventions of the ‘Golden Age’ detective novel.

Unlike Leo Bruce’s wonderful 1936 spoof Case for Three Detectives, which sends up the fictional characters of classic Golden Age mysteries, Eight Detectives concentrates on the mechanics and plotting. Grant McAllister, professor of mathematics and Golden Age crime writer, was also the author of a research paper, The Permutations of Detective Fiction, a schema by which all detective novels could be categorised, but after limited success, McAllister gives up writing fiction and retreats to a Mediterranean island to live as a recluse. Thirty years on, an ambitious young editor tracks him down with a view to republishing a collection of his short stories which ‘prove’ his mathematical theories.

The reader is then treated to seven short stories and accompanying notes and observations from the young editor as she goes through them with an ageing and uncertain McAllister. The stories contain multiple nods to the ‘Golden Age’ in terms of plot, motive, misdirection and fantastical methods of murder (plus the familiar trope of the murderer conveniently dying from a consumptive disease) and one in particular is a brilliant homage to the book I am told I must now refer to as And Then There Were None.

But the stories in Eight Detectives are a smokescreen for the real duplicity behind them, which is cleverly revealed in multiple endings, proving that Alex Pavesi is almost as clever as the fictional Grant McAllister when it comes to getting away with murder.

As far back as 2006 I was having doubts about James Lee Burke’s fictional detective Dave Robicheaux, worrying that the character I had so much admired for almost two decades was turning into a bit of a bully. More recently, Robicheaux has kept his conscience clear for his frequent visits to Mass or AA meetings by sub-contracting most of the bullying to his sidekick Clete Purcell and a particularly unpleasant theme was emerging.

In Robicheaux (2018) he sadistically beats up a ‘suspect’ in a lavatory whilst the psychopathic Purcell attacks two hoodlums in a public lavatory. In this he had form having, in the previous book, tortured a man in a lavatory by making him eat disinfectant urinal cakes. It was thus with some trepidation that I approached A Private Cathedral [Orion] and, sure ’nuff, by page 25 there was Clete viciously smashing a man’s head into a toilet bowl, a man he was happily strangling with a bedsheet until he notices a convenient lavatory. And he’s doing this because, as usual, someone has ‘disrespected’ his friend Robicheaux or looked at him in a funny way, which is why Robicheaux calls him his ‘noble mon’. If Clete Purcell really is a Sancho Panza figure, then it’s a Sancho Panza carrying a pair of grenades with the pins out.

None of this worries Robicheaux (is it just me?), who thinks of Clete as ‘an archangel in disguise’ and a character with a ‘Biblical dimension’, as he continues his philosophical search for the ‘origins of human cruelty’ though in truth he needs look no further than Clete Purcell’ abusive upbringing. Still, that’s no justification for allowing Purcell to perpetrate, on his behalf, some distinctly nasty violence because his pride has been hurt.

As usual Robicheaux seems convinced that evil is somehow genetic, rarely giving a thought – in the southern states of the USA – that violent crime and corruption might have something to do with the massive gulf between the richest and the poorest and the legacy of that ‘peculiar institution’ slavery.

Burke’s legendary baroque prose and lyrical style are still much in evidence and you have to admit that any crime novel which uses words such as riparian and solipsistic can be rather beguiling, if one can only get over the insistence on lavatorial mayhem.

Arriving too late for decent consideration this month, two American thrillers I have been looking forward to.

On the cover of Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Evolution [Head of Zeus] you have two of thrillerdom’s most famous names in Ludlum and Bourne, yet it is the third name there, that of author Brian Freeman, which has secured the book’s place on my summer reading list. Freeman, in his own right, is a dab hand at tough, suspenseful crime thrillers and his name should be better known in this country.

The advance publicity for Robert Pobi’s Under Pressure [Hodder] suggests a plotline similar to that – for those of a certain age – of Philip MacDonald’s The List of Adrian Messenger, where a large number (an aeroplane full) of people are murdered to cover up the sole, intended victim. Robert Pobi uses a precision bomb attack on the Guggenheim Museum rather than sabotaging a trans-Atlantic airliner, but out of 702 victims, was there only one real target? If anyone can tackle this mystery, Dr Lucas Page can. He is a former FBI agent turned university professor and astrophysicist, which sounds unlikely, but he proved himself resourceful enough in Pobi’s excellent City of Windows last year.

And the Book Comes Later

I can stand it no longer and must protest. Over the past two months I have noticed a disturbing number of reviews of crime novels which have praised particular works to the extent that I was sorely tempted to read them, yet a modicum of research showed that the reviewer was referring to a ‘Kindle’ version (whatever that is), and the real book was not to be available for many months. There was absolutely no mention of this fact in the glowing reviews and indeed the price quoted for each title was that of the (unavailable) hardback edition.

I could name and shame three well-known reviewers guilty of misdirecting potential readers this way, but I have a new crime novel out and so will refrain.

And So Does the Next Column

This is advance notice to my loyal reader that next month’s Getting Away With Murder column is unlikely to appear until mid-September.

From now until then I have been recruited by a leading market research company to conduct an important poll of the reading public. My brief is to give one hundred members of the public one hundred seconds to name the murderer in The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman, which is to be published by Viking.

The exercise strikes me as fairly pointless, but the money’s good.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|