|

When A Subtle Knife Won’t Do

It has long been the philosophy of this august magazine [Ezine, you old fool. - Ed.] to recommend goodcrime novels to its many readers worldwide, rather than rubbish those which offer up derivative plotting, cardboard characters, inadequately-researched settings and flavourless prose. (It is rare to find one which demonstrates all four flaws, but it is not unknown, and indeed those can occasionally be found at the top of the bestseller lists.)

I will therefore neither name nor shame a new debut crime novel which threatens to be the first of a series, but within the first sixty pages, it commits - not once, but twice - a cardinal sin in my book by getting local newspaper coverage of a murder so badly wrong. When a gruesome murder is committed and a body part removed from the victim, the details are never immediately released to the media and no newspaper would print them anyway, no matter how much it helped the plot along.

I can forgive a crime-writer fudging police procedure, because the most effective police procedure is usually painstakingly dull. (Colin Dexter always used to say he didn’t ‘do’ police procedure because he didn’t know any.) But it should not be beyond the wit of the would-be crime writer to read a newspaper now and then to see how it should be done.

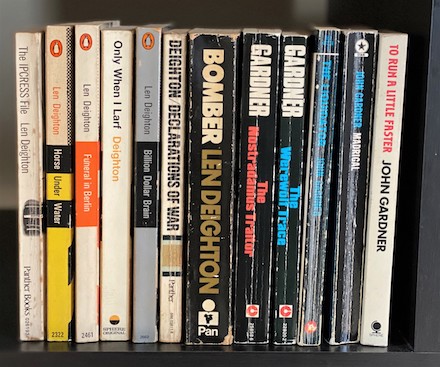

This month’s debutant is by no means the first to strain disbelief when featuring newspaper reporting of a murder and certainly won’t be the last. I did enjoy one aspect of the book, however, as the author, clearly seeking inspiration for the names of two subsidiary police officers glanced up from the keyboard and ran an eye along a convenient bookshelf stocked with much-loved paperbacks:

And thus the characters of DCI Deighton and DS Gardner were born. Oh, come on, we’ve all done it.

Memoirs Are Made Like This

Biographies of writers vary enormously from the revealing (and hopefully salacious) to the worthy but dull, to the downright awful. But then writers are an odd bunch, either reticent about life outside their fiction or prone to exaggeration. The best thing a biographer can do is probably rely on the writer’s own words as, after all, that is their business, and be an editor rather than a hagiographer.

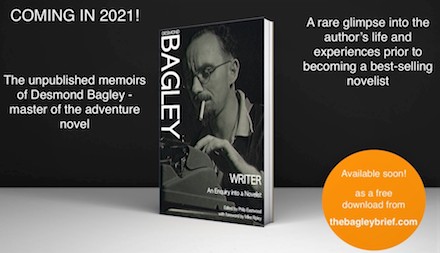

Which is precisely the role Philip Eastwood has adopted in his painstaking reconstruction of the memoir Writer: An Enquiry into a Novelist from raw material left by Desmond Bagley (1923-83), a master craftsman of the adventure-thriller and, in his heyday, one of the ‘Big Three’ of that genre along with Hammond Innes and Alistair MacLean.

Begun by Bagley as an exercise in formulating a coherent answer to all those ‘how do you..?’ questions thrown at writers and left abandoned for many years, Writer has been rescued from the archives by Philip Eastwood and embellished with his own extensive research into the current Memoir, which will be made free for download via the website www.thebagleybrief.com as of 1st March. It covers Bagley’s early life from wartime Britain to his overland trek to South Africa in 1947 and his career in journalism before his rather more stellar career as a thriller writer, despite the fact that Bagley himself wrote: This is not an autobiography. I have not led so interesting a life as to want to embark on such an enterprise, a statement many would disagree with.

Thanks to the wonders of modern technology, I am told that it will even be possible to read Writer on a telephone.

In my world of course, this smacks of witchcraft but I feel that Desmond Bagley, who was always happy to embrace new technology, would approve.

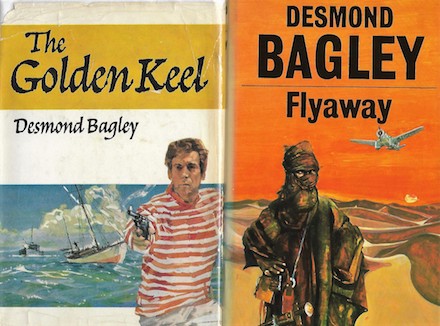

Of the many fascinating things I learnt from other research material uncovered by Philip Eastwood was that following the success of his novel Flyaway, set in the Sahara and among the Tuareg clans, Bagley was approached by Professor Glyn Daniel ‘at Cambridge saying he was organising an anthropological expedition to study the exact impact of modern conditions on the lives of the Tuareg’. Bagley generously agreed to contribute to the financing of the expedition, but it is not clear whether he knew that Professor Daniel was himself the author of some noted works of fiction.

Comfort Reading

One unsung consequence of the current plague is that due to staff shortages, the postman only calls at Ripster Hall once every eight days, which has meant a dearth of new books thudding on to the driveway from a speeding red van. This has resulted in several lulls - often far too short - in the crowded reading schedule forced upon me by publishers and publicists.

I have used these brief moments of quietude to reading authors whose work I have long regarded as comfort food, in that their books are easy to digest and usually leave me warm and satisfied. And so I turned to a previously unread Victor Canning, The Chasm, from 1947.

By that time, Canning (1911-1986) had published a dozen or so picaresque novels pre-war and a war story during, but as he resumed his writing career after military service, he took a different turn towards the thriller. Not that The Chasm was a conventional thriller, in that it clearly started out as a reflection on the aftermath of war, then morphs into a romantic novel before, in the last quarter becoming a suspenseful revenge thriller. Although something of a mish-mash, publisher Hodder gave it a first print run of 15,000 such was Canning’s reputation, despite the fact that it was his first book for several years. It was a book where Canning seems to have been experimenting with the thriller and, finding the genre to his liking, he then produced a slew of them in the 1950s (and beyond), many of which were filmed.

The setting is Florence and northern Italy immediately after the end of WWII; an area in which Canning had served in his army days and which he describes lovingly through the eyes of a depressed ex-army officer called Burgess, who is drinking too much whilst working for UNRAA, the United Nations relief agency. (The initials must have been well-known at the time as Canning never bothers to explain them.) Burgess mooches around a superbly-evoked war-damaged Florence and then heads off to a tiny village in the mountains as winter sets in quicker than expected. Cut off by a collapsed bridge, he discovers love-at-first-sight, finds an old enemy and makes a new one. At this point, Canning the thriller writer kicks in.

The Chasm is by no means the best Canning, but it is an interesting one, showing a writer, after his wartime experiences, switching to a tougher, more suspenseful style. It also references the work of American novelist Joseph Hergesheimer and uses the word herisson, neither of which I had ever seen before in a popular thriller. Details of Canning’s life and work can be found on the exhaustive dedicated website curated by John Higgins at http://canning.marlodge.net/ and for lovers of trivia, the literary estate of Victor Canning is controlled by his godson Charles Collingwood, the actor best known for playing Brian Aldridge in The Archers.

I am not, I see, alone in this nostalgic bent, as in recent weeks I have read articles by noted media personalities waxing lyrically on how they have enjoyed revisiting novels by Ira Levin (the outstanding A Kiss Before Dying, a book as old as I am but which has held up far better), Porterhouse Blue by my former history tutor Tom Sharpe, and the novels of that master storyteller Nevil Shute.

Inspector Bucket and Sergeant Cuff

I am not sure whether it was a dark and stormy night when Irish mystery writer Cora Harrison had the idea of teaming up Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins as detectives in her Gaslight Mysteries series. As they created two of the nineteenth-century’s earliest fictional detectives (Bleak House and The Moonstone if you have to ask), surely they would be a dream team at solving crime.

In Harrison’s third ‘Gaslighter’ Summer of Secrets, out now from Severn House, the pair are at Knebworth House for a special event. No, not an early incarnation of Led Zeppelin, but a performance by the house guests of a play written by the owner Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, whose best-selling prose took, as one of the characters admits, quite an effort ‘to wade through’.

Bulwer Lytton, still famous for coining the phrase ‘The pen is mightier than the sword’ for the film Indiana Jones and the last Crusade [Are you sure? - Ed.] and, of course, the most cringeworthy opening line in fiction, turns out to be a bit of a cad, at least in the way he treats his wife (and dogs) and is surely ripe to be murdered. After all, we have a country house, a closed circle of unpleasant suspects all with suitable motives and the presence of two literary detectives. It can only be a matter of time before a shot rings out, and it does in suitably theatrical fashion. The victim, though, is not Sir Edward, but should it have been?

Step forward Bucket and Cuff, or rather their alter egos, to solve the case.

Postbag

Whilst the snail-mail may be intermittent, my electronic post box was flooded in January with Happy New Lockdown messages, one even challenging my liking for Amarone and recommending instead a Negroamoro from either Sicily or Puglia, to accompany my February reading chores, the wine being readily available via ‘Aldi’. If only I knew what an ‘Aldi’ was.

A senior figure in publishing sends her greetings along with the uplifting sentiment that we should ‘remind ourselves how lucky we are to work in a business that makes something people can enjoy on their own...’ If by this she means that a good crime novels can be seen as an effective way of making readers stay home and stay safe, then surely all involved in producing them are eligible for a government grant. And I can think of no other stimulating activity which people could enjoy on their own, although I will probably be told of one.

Praise, like alcohol, is said to be dangerous for writers, though I’ve never fully subscribed to that maxim. Which is why I delighted on the way the January column, launching another decade of Getting Away With Murder, was received. One regular correspondent thought it ‘whip smart as always’ another claimed ‘They seem to get more interesting all the time’whilst a long-time fan of the genre, and now an editor in it, wrote: Happy New Year, Sir M. I love your column; it always takes me back to the golden days of crime gatherings. Which is a lovely sentiment but clearly there is something wrong with her typewriter as instead of a full stop it printed an odd yellow blob with what appears to be a smiling face drawn on it. Perhaps this is a reference to modern drug culture which I do not understand.

In Remembrance of Time Teams Past

In my days as an archaeologist, the words ‘Night Hawks’ were always preceded by a very rude adjective, but in the latest addition to Elly Griffiths’ crowd-pleasing Dr Ruth Galloway series, they appear to be a fairly respectable society of metal-detectorists operating in North Norfolk.

I remain to be convinced, as although many a metal artefact now graces a museum thanks to the metal detector, many archaeological sites have been wrecked (usually at night) by unscrupulous ‘treasure hunters’. But in The Night Hawks [Quercus] the detectorists are the plot generators as their activities (on the coast at night) looking for Bronze Age treasure, lead to the finding of a body - one which has certainly not been dead for two thousand years and Dr Galloway is, once again, called in to help the police.

She is hampered rather than helped by a new recruit to the University of North Norfolk who is at times so obnoxious that he deserves a slap, the sort of archaeologist who sees a fragment of old metal and immediately assumes it is from a spear and therefore grave goods and immediately starts thinking of facial reconstruction on a skull (or even a grave) not yet found.

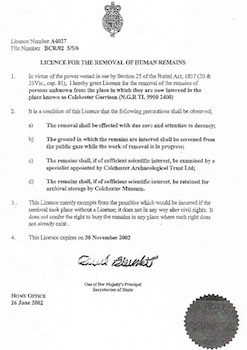

Ruth Galloway, however, has her head screwed on and realises she must do the right thing and apply for an official Licence For the Removal Of Human Remains. These are real things and I still have the last one I worked under when excavating graves dating from Roman Britain.

They are issued by the Home Office and mine was signed by the then Home Secretary, David Blunkett. Ruth Galloway’s licence will presumably come signed by Priti Patel, and if she doesn’t frighten off the illegal night hawks, nothing will.

|

|

BOOKS OF THE MONTH

Is it really sixteen years since Argentinian mathematics professor Guillermo Martínez gave us the much-lauded (and bestselling) The Oxford Murders? It seems so, but at last the enigmatic narrator, known only as ‘G’, returns to Oxford to apply various types of mathematical logic to the problem that was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, an eminent Oxford mathematician as well as the author, under the pen-name Lewis Carroll, of some rather famous stories.

The Oxford Brotherhood [Little Brown] centres on the diaries of Lewis Carroll, or more specifically on pages torn from them which have been found by an enthusiastic researcher and are about to be presented to the ‘Brotherhood’ - an organisation of dedicated Carroll fans. Salacious photographs of a young ‘Alice’ then start to be circulated, supporting the rumours about the author’s unhealthy interest in young girls, but not before the researcher is the victim of a suspicious road accident.

Fluently written and seemingly flawlessly translated, this is an intriguing cocktail of mystery and literary detection with some memorable characters. One, an eccentric Englishwoman, has a party trick whereby she can, blindfolded, tell which cup of coffee has had the milk put in first.

Here I feel Guillermo Martínez is betraying his South American heritage, for surely any Englishwoman worth her eccentricity would insist on performing the trick with cups of tea. My chum the late Reg Gadney always answered any question or survey on his religion by declaring he was a predelictantlactatarian because he preferred the milk in first, but I don’t think even he, a noted prankster, ever claimed to be able to tell the difference in a blind tasting.

If anything is going to put people off going on an ocean cruise apart from the threat of a virus or having to sit through after dinner lectures by crime writers, then it will be Passenger 23 by Sebastian Fitzek [Head of Zeus] despite the protestations of the author who says he really likes them.

Passenger 23 basically suggests that the reason 23 people disappear each year from cruise ships is because there may be a serial killer or two on board. When one ‘victim’ disappears only to reappear in a catatonic state two weeks later, who better to send to investigate than Martin Schwartz, an undercover German cop with a bit of a death-wish, following the disappearance of his wife and son from - you guessed - a cruise liner some years before. Our hero uncovers an incredibly twisted tale of murder, torture and sexual abuse (and be warned, some bits are graphic) along with a transgender theme which I am not going to comment on. There is even, in a coda to the main plot, an example of cosmetic surgery of the most extreme kind.

The whole thing is bloody, breathless, deliberately discomforting and outrageously gripping.It was back in 2008 when I tipped German author Sebastian Fitzek for great things after his chilling debut thriller Therapy appeared in English and this could be his year, with other translated titles, Seat 7a and The Soul Breaker, appearing in April and August.

The thing that’s always amazed me about (fictional) serial killers is where do they find the time? Not to do the killing, but to elaborately arrange their victims as ghastly trophies. A prime example of this was shown, tongue in cheek (well, somebody’s tongue...), in the television series Hannibal where we were treated to an over-the-top portrait of the serial killer as a sort of psychopathic Raymond Blanc.

In David Fennell’s The Art of Death [Zaffre] the serial killer is a sort of psychopathic Banksy, leaving gruesome examples of his work as art installations all around Central London, not giving a fig for the Congestion Charge, and, perhaps not surprising in London, only when someone starts screaming are they noticed.

Just when you thought the serial-killer thriller had gone as far as it could, David Fennell attempts to breathe new life (okay - poor choice of words) into the genre, though by calling his police detective protagonist Inspector Grace Archer, he is bound to raise the hairs on the necks of dedicated Radio 4 listeners of a certain age.

Veteran thriller writer Gerald Seymour changes tack from his usually exotic and invariably dangerous locations to set his new novel The Crocodile Hunter [Hodder] almost entirely in comfortable southern England. The plot line is, however, uncomfortably topical.

When young British jihadi fighters begin to drift back from the Middle East after fighting under the black flag of Isis, bent on a final act of violence, the Security Service refers to them as ‘crocodiles’ because they lurk beneath the surface waiting to strike. To track, trace and catch them, a crocodile hunter is required, and the one created by Gerald Seymour is Jonas Merrick, a methodical, desk-bound, unflashy operative nearing retirement who was known (behind his back) as ‘the Eternal Flame’ until a close encounter with a suicide bomber earns him a reprieve from retirement and the title ‘Wobby’ - Wise Old Bird.

Merrick, with his flask, sandwiches, suburban routine and caravan holidays is so unlikely a spy, he’s probably the perfect one, everything about him seems so mundane. As a fictional hero he is a world apart from George Smiley and a universe away from James Bond, but when the final showdown comes with a dangerous lone fanatic who has made it back from Syria by crossing the Channel with a party of illegal immigrants, Merrick proves to be just as resourceful and just as brave.

Those wonderfully generous people at Stark House Press in California are determined to educate me in classic American noir which may not have managed to cross the Atlantic and they have sent me their new Black Gat edition of Hoodlums by George Benet, first published in 1953.

As far as I can tell, this was the only noir tale, about lowlife in Chicago, written by George Benet (1918-1990) under the pen-name John Eagle and despite selling half a million copies, Benet abandoned the novel (although he did produce other work later in life) in favour of work as a longshoreman in San Francisco. He was a life-long member of the ILWU - the dock-workers union - which probably marked him down as a dangerous socialist in American eyes, though I’ve never been totally convinced that Americans know what a socialist is.

A good private eye novel is like a smooth single-barrel bourbon and a new Easy Rawlins tale is to be savoured in the same way. Walter Mosley’s Blood Grove [Weidenfeld & Nicholson] contains all the traditional ingredients: the client with a problem appearing in the PI’s Los Angeles office (where desk drawers come complete with a bottle of bourbon), car trips out into the Californian hills, deserts and (blood) orange groves, telephone calls from gas stations, and a truly spectacular femme fatale.

The Rawlins books may be reminiscent of Ross Macdonald at his best, which is praise indeed, but with Rawlins being a black war veteran and this being 1969 with another war in progress, Walter Mosley puts his own individual stamp firmly on the private eye genre.

If you like your mysteries set in wild and rugged places, look no further than the Alaskan settings employed by Dana Stabenow. The Spoils of the Dead [Head of Zeus] is the fifth novel in her second series, following her successful ‘Kate Shugak’ series, featuring State Trooper Liam Campbell.

It is a cosy mystery featuring some well-drawn female characters - the male ones less so - and it’s a good hundred pages before we get to a murder, but the detail about Alaska, its history, geography and population, which Stabenow packs in is fascinating stuff. For instance, I learned that the expression ‘the bush’ is used in Alaska for the wildlands beyond any urban area, no matter how small, whereas I had always associated the term with the hotter, desert regions of Australia or southern Africa, but then I’ve always maintained that crime fiction broadens the mind.

This was the first of Stabenow’s Liam Campbell books I have tried and clearly am missing much of his back story, and it has left me intrigued as to why his perfect (too perfect?) wife is called ‘Wy’.

No Trumps

As regular readers know, for almost twenty years, this column has never commented on politics (belittling Brexit-voting Little Englanders doesn’t count) and certainly not American politics. Now that President Trump has retreated gracefully to a golf course somewhere (but not Scotland), however, I feel safe to share the following.

I have not, to my knowledge, ever met an American private citizen who owned a gun. Similarly, though I may be naïve, I have never met an American who has admitted to voting for Trump - save one.

It was at a well-known crime-writing convention (remember them?) shortly after the 2016 election and a casual meeting in a bar with an American delegate (not a crime writer) somehow led to a discussion of the, as I saw it, rather incredible result. My new American friend turned out not only to have voted for Trump, but declared themselves an active and enthusiastic supporter. When I asked them why, they replied simply and without explanation: ‘I’m from the South.’

It was a rather chilling full stop to the topic.

French Vocab.

Many loyal readers of this column - far more than I imagined or hope for - are suffering withdrawal symptoms following the final episode of the excellent Spiral. However, I can offer hope and succour to those who wish to continue to expand their familiarity with and pronunciation of Parisian obscenities.

Call My Agent (Dix pour Cent), now on Netflix, is not a cop show or a crime drama, but rather a satire on the world of talent agents and film production. It is tightly written, brilliantly acted and absolutely hilarious. An English version is, I understand, being made and one hopes for the best but fears the worst, which I suppose is the motto of all agents.

Zut alors!

I am told that despite the pandemic, the English cricket team did rather well last month in a Test Match in Gaul. Who knew the French played cricket?

Welcome to 2021 – “The Sequel”

The Ripster.

|