|

A Day That Will Live In Infamy

The dedication in Michael Ridpath’s new novel The Diplomat’s Wife (see Books of the Month) struck a particularly poignant note with me as the book is dedicated To the English country pub. May it open soon.

Whilst totally sharing the author’s sentiment (and Michael and I have had learned discussions in the past on the history of ale, usually on licensed premises), I was reminded by it that the 12th of this month is a date forever scarred in my memory as it marks exactly one year since I was last in a British public house.

I remember the occasion well, as it also marked the last publishing party I attended, thanks to the generous hospitality of those charming publicists at Headline and the last time I was able to enjoy the company of my Shots colleague, the voluptuous Ayo Onatade.

But my message to Michael Ridpath is that the pubs will re-open at some point and all those drinks I have been promised in the past year will be accepted. I have been keeping a list...

True Colours

Last month I suggested that best-selling author Elly Griffiths might be more sympathetic than I to those buccaneer metal-detectorists which feature in her latest novel The Night Hawks.

In April, a new novel by up-and-coming thriller-writer Russ (not Ross) Thomas, Nighthawking [Simon & Schuster] investigates, so I am told, the secret world of treasure-hunters who operate under cover of darkness, seeking the lost and valuable, and willing to kill to keep what they find.

That sounds more like it.

Old Jokes?

Whilst wading through the deluge of March titles which suddenly appeared after a very slow start to the year, I spotted two examples of humour (something I tend to look out for) which got me thinking, as well as laughing.

In his latest novel, Chris Brookmyre (see Books of the Month) describes one character (I paraphrase) giving another a sarcastic ‘Nancy Pelosi’ round of applause. Now I know what he means by that, but will a post-Trump reader get the reference in the future, or even by the time The Cut comes out in paperback?

Similarly, Mick Herron, in his latest bestseller Slough House, makes a joke about Chris Grayling, but surely we will soon have forgotten about him, won’t we? Please say we will.

I Spy

I remember being very impressed with John Fullerton’s The Monkey House, set in war-ravaged Sarajevo, when it first appeared in 1996, but cannot think of anything else of his I have read since. However, the memory of that impressive debut was triggered when I discovered that Fullerton was back in the spy-fi game, with the aptly titled Spy Game [Burning Chair].

And the fact that I discovered his new book thanks to a very positive review by Russell James in this very eZine (https://bit.ly/3c5n63v) only peaked my interest further, as Russell is a connoisseur of the hardboiled.

In Memoriam

I was saddened to hear of the death of American mystery writer, and good family friend for more than thirty years, Margaret Maron although I knew she had been ill since before Christmas. I was asked to pen a hasty tribute for the Shots Confidential blog (https://bit.ly/30dczxq) and since that appeared numerous people have been in touch offering sympathies and sharing memories.

Although far better known in America, where she was active in the MWA and Sisters-In-Crime, than here, there was a time when Margaret Maron paperbacks occupied several shelves in the original Murder One on Denmark Street. After early success with her New York-set police detective stories, her second series of novels featuring North Carolina county judge Deborah Knott won her multiple awards and began a trend in ‘regional’ mysteries set outside the big US cities, which brought forth many imitators. Margaret, however, drawing on her North Carolina heritage, was a hard act to top and her obvious affection for her home state brought her further local honours. Astonishingly, none of her books were ever optioned for television.

It became something of a regular event as to whether she or another good friend of mine, Canadian Louise Penny, would win the annual Agatha Award at the Malice Domestic convention, and a great rivalry between the two was widely gossiped, though I suspect they got on quite well together and once combined to send me photographic evidence of how much they enjoyed this column.

She was a generous host, a generous person in fact, who delighted in showing off her home state’s natural beauty and its culinary traditions. These included several in-depth lectures on the perfect barbeque and a masterclass in making ‘red eye’ gravy, as well as a visit to the home of Krispy Kreme Donuts. Best of all, she introduced me to Quail Ridge Books, her favourite bookshop, where she regularly hosted visiting authors, including Ian Rankin.

Margaret Maron was the first American mystery writer I ever befriended, but then it was difficult not to become a friend once you had met her, and she was fiercely loyal, rarely having a bad word to say about anyone (certain American presidents excepted). In a rare moment of carelessness, however, she did tell me a juicy piece of historical gossip about the Mystery Writers of America.

Over the years, we hosted the Maron family on trips to darkest East Anglia, Cambridge and Oxford. In turn, they hosted us in North Carolina from Boone in the west to Harkers Island on the Outer Banks in the east, where the Marons and the Ripleys, armed with a jug of Margheritas sat out a hurricane in 2004.

Several jugs, actually.

I Am (A) Legend

One of the great pleasures of this game is finding something new, or discovering something old for the first time.

I have long been an admirer of the work of Richard Matheson (1926-2013), as has - to drop one famous name - Stephen King, primarily for his contribution to horror fiction in classics such as I Am Legend and Hell House. But I was also well aware of his contribution to the sci-fi and crime fiction (and Westerns) genres.

I was, though, unaware that he had written an autobiographical novel based on his experiences in the American army during World War II. First published in 1960 and, as far as I can tell, out of print in the UK since 1975, The Beardless Warriors is set over a two week period in December 1944 on the front line in Alsace in France.

It is a simple story of very young men, members of a squad of infantrymen, who are thrown into battle in a hostile landscape against an enemy they don’t really understand and rarely actually see. The fact that they are young and relatively innocent is rammed home by the central character’s near obsession with how many of his squad’s replacements are only eighteen, with one veteran sergeant saying ‘I ain’t running a rifle squad, I’m running a kindergarten’.

References to the youth of the squad, as they go through their first terrifying combat actions, dominate the book, as do the references to the various bits of equipment an infantryman has to carry and look after (another obsession is keeping a rifle clean), all of which indicates that this was written by someone, aged 18, who had been there and had to do that.

Revivals of the Month

Two authors a world apart in backgrounds and in the scope and style of their crime fiction are having large chunks of their backlists reissued.

Rightly published as Penguin Modern Classics this month are five novels in the famous ‘Harlem Detective’ series by Chester Himes (1909-1984) featuring that magnificently-named detective duo of Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones.

Having suffered considerable discrimination in his native America, including as a scriptwriter in Hollywood, Himes turned to fiction whilst in prison, but it was after leaving America to live in France in 1953, that he wrote his best-known hardboiled crime novels. (He wrote in English though several were first published in French).

In 1982, Harry Keating’s seminal Whodunit? guide to crime fiction said of Himes: ‘He wields that pure, revealing magnifying-glass on life, showing it to us clearly for what it is, a weapon not given to every fiction writer by any means. He is extraordinarily funny; his vision is fundamentally tragic.’

From a middle-class English upbringing, Anne Morice (Felicity Worthington Shaw, 1918-1989) turned to crime-writing in 1970 with Death in the Grand Manor and was to write 25 novels in total, the vast majority featuring her amateur sleuth, Tessa Crichton an actress married to a Scotland Yard detective.

In April, Dean Street Press are to reissue ten of Morice’s Tessa Crichton mysteries, including Death of a Gay Dog from 1973. Tessa’s theatrical background was not coincidental, as Morice worked in the film industry before WWII and was a distant relative of one of England’s premier thespian dynasties, the Foxes (as in Edward, James, Emilia, Laurence, Freddie, etc. etc.)

The (Real) Thick of It

A life in politics clearly does not supply the suspense, danger, suspicion and back-stabbing it once did and to compensate, two stars from different parts of the political firmament have taken to thriller-writing.

Long-serving Labour MP and former Home Secretary (not to mention best-selling memoir writer) Alan Johnson is to enter the fray with Late Train To Gypsy Hill published by Wildfire in September.

He will be up against political guru Robert Peston whose thriller The Whistle Blower appears from Zaffre in the same month.

Lockdown Comfort Reading

In the long dark nights of the winter lockdown, I have, like many, taken to revisiting favourite authors of old. One of my preferred writers of adventure thrillers - and a favourite of Ian Fleming - has always been Berkely Mather, now very much a ‘forgotten author’ and it was on that basis that I was supposed to talk about him at the 2020 CrimeFest, and then again at the 2021 CrimeFest. Sadly, neither was to be even though I had already had the t-shirt printed.

Mather (John Weston Davies, 1909-1996), after a military career in India and the Middle East, made his name as a scriptwriter of radio and early television dramas before his first novel appeared in 1959. His contemporary thrillers (he also wrote historical novels) all had themes of espionage and he had a trio of heroes who sometimes collaborated, sometimes worked alone. They were perfectly summed up by an Anthony Price review: ‘Action, pursuit, violence and villainy’.

With Extreme Prejudice, first published in 1975 certainly has plenty of the ingredients Anthony Price identified, plus a plot which involves an international gang of hi-jackers and a sympathetic, n’er-do-well narrator who is dragged back into intelligence work against his better judgement. As with all Mather’s adventures, the characters face tremendous physical hardships and there’s a lot of hard marching involved, but what adds value to the mix here is the setting: the Suez Canal (post the Egypt-Israel Six Day War) and the island of Cyprus and I cannot recall reading any other thriller set in the war damaged Canal Zone.

It was a part of the world Mather/Davies knew well as after leaving the regular army he served with Military Intelligence in Egypt in the early 1950s, trying, it seems, to prevent the Nasser coup which deposed King Farouk. I have a feeling he was a better thriller-writer than an undercover agent and by all accounts he was extremely popular with the female members of the Crimes Writers Association, of which he became chairman.

Diamond Martina

I am truly delighted to hear that my old chumette Martina Cole (we are members of the same London club) is to receive the Diamond Dagger from the Crime Writers’ Association later this year.

I am relieved that whoever dispenses this honour chose to ignore the ugly rumour that Martina, some twenty years ago, was photographed in the company of known hooligans...

|

|

Books of the Month

(Part I: Scotland)

A septuagenarian ex-jailbird, having served a 25-year sentence for murder, and a young film studies student with a talent for petty thievery make for an unlikely pair of heroes in a road trip of a thriller which rocks and rolls from Glasgow to Paris to Rome to the ruins of Pompeii in Chris Brookmyre’s The Cut [Sphere]. En route to the final justice being sought by former film make-up artist Millie who was, of course, framed for the murder, the couple are pursued by corrupt policemen and assorted gangsters, and discover a cover-up with political implications in the bowels of the Italian horror film industry in the days when films went straight to VHS.

Chris Brookmyre, being Chris Brookmyre, has lots of fun with this scenario, which revolves around a ‘lost’ (and therefore cursed) Italian horror epic and with his student hero’s obsession with t-shirts promoting Heavy Metal music - ‘the whitest form of music known to man’. The humour is mostly on the dark side, and spiked with needles of Scots vernacular - I can make a case for why I hit the guy with a hammer, but I cannot claim I yeeted his body into the river in self-defence.

(Spoiler alert: the ‘yeeting’ of a dead body off a bridge doesn’t exactly go to plan.)

The Cut sees Brookmyre on top sarcastic form tilting at many a windmill and managing to skewer most of them.

For a different take on the high and low life of Glasgow, this time the Glasgow of 1899, I can recommend seeing the city and its crimes through the lens of the camera of photographer-sleuth Juan Camaron, who brings to those mean streets, concert halls and tenements a fascinating Scots-Cuban personal history. The Art of the Assassin by Kevin Sullivan [Allison & Busby] is Camaron’s second outing and apart from providing a fluent historical mystery, gives an absorbing account of how photography became a vital part of police forensic investigations.

Glasgow, 1974, when HMP Barlinnie had the reputation for being the most environmentally-friendly prison in Europe (because all the lead from its roof had been removed), and was where even hardboiled police detectives like Harry McCoy can’t stand the sight of all the blood.

With The April Dead [Canongate], Alan Parks has given us an absolute belter of a crime novel with a multi-layered plot and a police hero who could, one day, be ranked up there with Laidlaw and Rebus. Harry McCoy may be a tad squeamish, and have too many dodgy friends from the wrong side of the legal tracks, but his heart is in the right place and his creator imbues his story with the dry self-depreciating wit which made the audiences at the Glasgow Empire notorious.

In a burst of Good Samaritanism, McCoy gives a visiting American, after a trans-Atlantic flight, a lift to Aberdeen and they stop at a roadside café for breakfast. The American orders freshly-squeezed orange juice, pancakes with maple syrup and a side order of crispy bacon. He is served with a sausage sandwich and a can of Fanta. Welcome to Scotland.

(Part II: Everywhere else)

In The Fine Art of Invisible Detection [Bantam], Robert Goddard plumps for an unlikely protagonist, a quiet, middle-aged Japanese widow working as a secretary for a Tokyo private detective. Umiko Wada actually has no ambition to becoming a detective herself, but fate doesn’t leave her much choice and the mousey Umiko has to adapt to something of a jet-set life as the investigation more or less dropped on her, involves travel to London, Exeter, New York and Iceland where she has to prove she can take care of herself when things turn violent.

Robert Goddard is a thriller writer who is never content with one plot-twist when three will do and reveals more about the development of Sarin gas than I was comfortable knowing. He also cannot resist the necessity, by all foreign writers, to comment on the weather in Iceland: Sunday in Reykjavik was no less bleak than Saturday, with drizzle, sometimes intensifying into rain, drifting across the grey city.

A gap-year (as we would say now) road trip around Europe in a flash sports car, all expenses paid, would have surely appealed to any red-blooded 18-year-old male in 1979, but with your granny as a travelling companion? If, however, your nan was a British diplomat’s wife in Paris and Berlin of the 1930s, a committed spy for the Comintern who travels with a revolver in her luggage, and is clearly on a mission to tie up old loose ends, then the journey becomes even more exciting, not to say a little dangerous.

Told as a twin narrative - the 1979 road trip with flashbacks to Europe on the brink of war - Michael Ridpath’s The Diplomat’s Wife [Corvus] is an engaging piece of spy-fiction which examines naïve loyalties and ruthless betrayals in both time frames, especially when the action moves to Cold War Berlin. The lesson for Phil, the innocent grandson and gap-year student, is trust no one, but he cannot resist the honey trap set by a young Stasi agent - blonde, naturally. It’s a good job granny knows how to use that revolver.

In my university days several centuries ago, I met a fellow undergraduate who hailed from Ormskirk in Lancashire. I mention this simply because I cannot recall having been conscious of Ormskirk in the years since, until now. Secret Mischief by Robin Blake [Severn House] begins with the murder of a prized pig in Ormskirk, no doubt a very serious crime in 1746, but which is quickly overshadowed by the murder of the pig farmer and the investigative duo of County Coroner Titus Cragg and Dr Luke Fidelis are soon on the case.

When the murdered man is found to be part of a seven-person tontine - whereby the last man standing scoops the pool of this rather bizarre non-life insurance wager (probably invented by the French) - there is no shortage of suspects among the other tontine subscribers, who have each invested £500, a staggering sum in 1746. The investigation undertaken by Cragg and Fidelis leads them into a particularly violent cricket match (this is Lancashire after all) as well as some very dubious drinking dens and alehouses where the favourite tipple, I learn, was something called bumbo - an explosive rum-based cocktail.

Trying to summarise the plot of Every Last Fear by Alex Finlay [Head of Zeus] is rather like trying to herd cats who have fallen into a pit of snakes. Any attempt to do so would be bound to confuse, so I won’t try. Thankfully, author Alex Finlay knows exactly what he or she is doing and in a bravura performance has given us an absolute cracker of a crime thriller about a miscarriage of justice over a gruesome small-town murder which leads to an appallingly cold-blooded cover-up.

A large cast of characters, different points-of-view narration and a likeable and competent female FBI agent, all keep the story moving at a fair lick, with some neat revelations and gut-churning twists along the way. ‘Alex Finlay’ is a pen-name and little information seems to be available about him or her. One thing I would bet a Nebraskan farm on though, is that Every Last Fear is not his or her first thriller. If it is, it won’t be their last.

I really liked Peter Swanson’s Rules For Perfect Murders even though (perhaps because) it irritated the purists who insist on ‘fair play’ detective stories. Whilst that book deliberately invoked memories of some favourite crime writers, his new novel, Every Vow You Break [Faber], reminds me of the early work of Ira Levin, which is no bad thing.

If I have a problem with it, it is because I personally find the main characters difficult to care about. The ploy revolves around Abigail who has a one-night stand with a complete stranger on her Hen Night or “Bachelorette Party” (though I’m not sure if either of those terms are politically correct these days, but then, what is?). The warning bells for Abigail should have started ringing with the handsome stranger’s initial chat-up line of ‘How many men have you slept with?’ which is not one I would recommend outside of a Channel 5 dating show.

Abigail’s intended is a strangely cold Silicon Valley millionaire and she does not seem too worried about cheating on him just before their wedding until she spots the one-night-stand stranger in the vicinity and things eventually turn violent on a weird ‘honeymoon’ island retreat off the coast of Maine. And I do mean weird, as in Wicker Man/Lord of the Flies weird.

The Mercenary by Paul Vidich [No Exit Press] is a vintage piece of spy fiction set in the bad old days of 1985, with a reluctant CIA agent sent to Moscow to ex-filtrate a defecting KGB officer. Naturally, in this kind of tale, Moscow Rules apply and Vidich plays it straight when it comes to the suspicion, fear and double-dealing as the opposing spies battle it out ‘old school’.

That The Mercenary is something of a throwback in terms of style and subject matter is not to disparage it in any way. In fact, if I told you just how good this spy story was, I’d probably have to kill you.

I was looking forward to reading Marcello Fois’ Valse Triste [MacLehose Press] as I had never read a crime novel written by a native Sardinian before. As it happens, Valse Triste is set mostly in Bolzano north of Lake Garda, although with many cultural and historical diversions along the way, which makes a complex, often poetic, tapestry of the narrative.

The core plot is a young, autistic child who goes missing and is thus a case for Commissario Sergio Striggio, but at the heart of the book is Striggio himself and his struggle as to whether to reveal the fact that he is gay to his father. It is a fascinating novel, sensitive and intelligent, which requires a certain amount of commitment and concentration from the reader, though that is well worth the effort if only to be able to say you have read a book where a character is described as looking more like a herm on the Janiculum than a hipster. (And, yes, I had to look up ‘hipster’ as well.)

I have greatly enjoyed Alan Judd’s recent diversions into spy fiction and am intrigued that his new novel, A Fine Madness [Simon & Schuster], centres on an Elizabethan spy scandal, the death of Christopher Marlowe, here treated as a ‘cold case’ being investigated years later, by a disgraced secret agent at the request of King James I.

Alan Judd brings his natural talent of writing firm, clear prose, as well as his background as a soldier and diplomat to bear on his version of a fascinating story, which was also the inspiration for Anthony Burgess’ A Dead Man In Deptford, a whole series of novels by crime-writer M.J. Trow featuring Kit Marlowe as a detective, and even in an outrageous short story, Our Man Marlowe, which may just be found in the anthology Angels and Others (see below).

Angels One Six

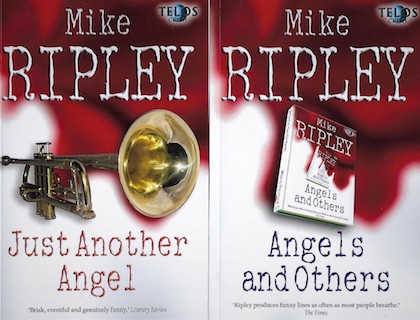

I hope I will be forgiven (like I care) for reporting that those splendid people at Telos Publishing have just produced new B-format paperback editions of all sixteen of my ‘Angel’ books, the fifteen novel series starting with Just Another Angel, plus the short story collection Angels And Others.

I thought I would mention this now as next month is April and I would hate for anyone to mistake this piece of shameless self-promotion as an April Fool’s Day prank.

Yours from the queue for

the second jab,

The Ripster.

|