|

An Auspicious Date

April 1st is an important date in the crime fiction calendar as it is the official opening date for taking bookings for the famous Chianti Crime Festival held in September. Not, of course, that the festival is always held in the Tuscan homeland of chianti, although its noble wine-makers have sponsored the event since its inception in 2013.

Last year’s convention of writers and readers from across Europe was scheduled to take place in ‘Bloodthirsty Bologna’ but had to be cancelled due to the pandemic. An alternative suggestion for 2021 has been the Sicilian city of Messina under the title ‘Murder In Messina’, to be held at the Hotel Savastano where the convention will have the run of both the Scylla and Charybdis executive suites.

In advance of the current travel restrictions and our exit from the EU, I decided I really had to go any check out the hotel’s super-fast WiFi and internet connectivity before a final decision is made.

(Very) Old Library News

Twenty-five years ago this month I was asked to establish a series of special features on popular genres in public libraries for the weekly trade newspaper Publishing News. As I was a regular contributor on crime fiction, that first edition of Library News was dedicated to some ‘arresting reading’.

It was an impressive spread, nobly supported with advertising from the then new Collins Crime imprint, and covered the latest titles by Lindsey Davis, John Grisham, Walter Mosley, Elmore Leonard, James Lee Burke, Robert B. Parker, Michael Dibdin, Val McDermid, Peter Lovesey, David Hewson and Jonathan Gash, among others.

I also made the effort, I’m proud to say, to highlight two relative newcomers to the dark arts of crime fiction, Stella Duffy and Colin Bateman, and a quarter of a century on, I stand by my recommendations, as most of the crime writers cited are still familiar names, many of them still going strong. Which is more than can be said for the Library News feature (I am not aware there was ever a second), or indeed Publishing News, which disappeared in 2008.

Postbag

Another interesting postbag - or should that be inbox? - followed last month’s column ranging from support for the reissuing of the work of Chester Himes to the revelation by a well-known crime-writer that he was asked to become a founder member of The Groucho Club in London’s fashionable West End, but turned down the invitation.

One correspondent commented on the featured cover of Berkely Mather’s With Extreme Prejudice, saying it was good to see an example of the painting of artist Dick Clifton-Dey (1930-1997), who was perhaps better known for his cover art on sci-fi and western novels. And a loyal Dutch correspondent picked me up on my rather dismissive remark about Ormskirk in Lancashire which he says ‘rang a bell even in the Netherlands’ as the birth place of crime writer E. S. Thomson, who now lives in Scotland and whose books, he says, ‘are certainly top-notch’. I was able to pass on the news to my eagle-eyed Dutch colleague that Elaine Thomson has a new novel, Nightshade, out this month from Constable.

Finally, in a charming missive from the west coast of America, I am commended for continuing to wear a tie at public events when so many have sadly allowed this invaluable fashion item to slip into extinction. I am already making my selection for the day the pubs re-open, so all those well-wishers who have promised to buy me a drink after lockdown (including, intriguingly, a ‘sconce’ of wine, which may be a challenge) should take this as a warning.

Lockdown Comfort Read

Lockdown and an erratic postal system have allowed me a respite in my gruelling reading schedule and allowed me to re-read some favourite authors or, in this case, discover a novel by a favourite which I had not read.

When first published in 1964 Philip Purser’s Four Days To The Fireworks was described by one reviewer as a spy story ‘more Graham Greene than John Buchan’, which is actually a  fair comment. There is a chase across unfriendly territory (East Anglia), in fact the whole story is one of pursuit, but no gunfights or cliff-edge moments, rather plenty of low-key domestic crises with a family of four, including a disabled boy and a baby, living out of a Mini-van as they try to flee the country. This is not a scenario where Richard Hannay or James Bond would have felt at home. fair comment. There is a chase across unfriendly territory (East Anglia), in fact the whole story is one of pursuit, but no gunfights or cliff-edge moments, rather plenty of low-key domestic crises with a family of four, including a disabled boy and a baby, living out of a Mini-van as they try to flee the country. This is not a scenario where Richard Hannay or James Bond would have felt at home.

Ten years previously, a young research scientist disappeared after passing secrets to the Russians, the scandal leading to the suicide (or was it?) of his team leader. But instead of fleeing behind the Iron Curtain, the missing scientist adopts a new identity, works as a humble garage mechanic, marries, has children and hides away in semi-squalor in rural Buckinghamshire. Until he is discovered, not by the police or MI5 (who seem to have forgotten him) but by a News-of-the-World style journalist. In a panic, he goes on the run with his family in an ill-planned escape via Cambridge to Boston in Lincolnshire with a pack of newspapermen on his tail.

The reader is never quite sure if the scientist did betray the secrets of a (long abandoned) military project back in 1954 or if he would ever face legal action if caught, but clues emerge along his escape route as it becomes clear his final destination is East Germany and then Russia. The tension in the chase/pursuit comes from small domestic incidents as our protagonist struggles to cope with a protesting wife, a disabled (insert a now politically incorrect description here) six-year-old and a crying baby in the days before disposable nappies, and the threat comes from the press hounds chasing the rather unsympathetic central character.

Four Days to the Fireworks was Philip Purser’s third novel and seems to have been a deliberate de-glamourisation of the boom in spy-fiction in the 1960s, whilst tapping into the existing paranoia about a ‘brain drain’ of British scientists. In contrast to the glitzy world of much spy-fi of the Kiss-Kiss-Bang-Bang era, this is kitchen-sink spy drama as well as, at times, a savage satire on popular journalism.

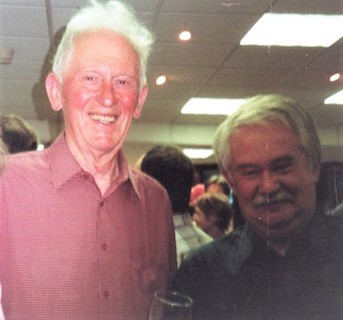

A journalist himself, Purser became known nationally as the long-standing television critic of The Sunday Telegraph from 1961 to 1987, as well as something of an expert on British films. He wrote only seven novels and I met him first just over ten years ago to edit a reissue of Night of Glass, his 1968 thriller about four Cambridge attempting to rescue a prisoner from Dachau concentration camp in 1968, as one of the titles which launched the Top Notch Thrillers imprint.

Interestingly, Night of Glass had a sequel, Lights in the Sky, published in 2005, some 37 years after the main characters first appeared and both are recommended.

I remember pointing out to Philip that 37 years for a follow-up wasn’t a record. It was 43 years before Rogue Justice, the sequel to Geoffrey Household’s classic Rogue Male, appeared in 1982. And, by the way, both of those are highly recommended too.

Mistaken Blues

When I first glimpsed the photograph of Mexican author Guillermo Arriaga on the jacket of his new novel, I was convinced it was a picture of the late Edward Bunker, former inmate of San Quentin and Folsom prisons, the author of numerous hardboiled crime novels and film scripts plus, famously, the actor who played ‘Mr Blue’ in Reservoir Dogs.

But it was only a trick of my fading eyesight and as far as I know Guillermo Arriaga has never been convicted of armed robbery or appeared in a Tarantino film, though he has written the scripts for numerous films, including 21 Grams, Babel and The Three Burials of Melquides Estrada (later shortened to Three Burials), the rather gruesome modern western directed by Tommy Lee Jones.

His new novel, The Untameable [MacLehose Press] is not, I think, a crime novel but rather a coming-of-age novel told in a parallel narrative of a boy growing up in the barrio of Mexico City in the 1960s and a native wolf hunter in the frozen north of Canada, with quite a few diversions along the way.

As biographical novels, this one certainly starts at the beginning - in the womb, with the narrator worrying that he has murdered his still-born twin - and then progresses through some toe-curling early sexual experiences to deaths within his family which leave him an orphan and seeking revenge against a corrupt policeman. Meanwhile, the wolf hunt in Canada continues and the narratives converge after 700 pages.

Arriaga is undoubtedly a powerful and highly respected writer, so the problem is with me rather than this book, but I definitely felt this was above my pay-grade.

Revival of the Month

I am not sure how many people read Georges Simenon these days. I do remember going on a UK author tour in the late 1980s with a British crime-writer who lived in Italy and at every bookshop we visited she would complain (very loudly) ‘why are there no Simenons on sale?’ Then there was a certain luminary (if that’s the word for someone who loomed over every meeting of the Crime Writers’ Association) who insisted that Simenon be always referred to not by name, but as ‘The Master’.

Whatever, it is good to see one of his non-Maigret novels from 1956, The Little Man from Archangel, now published in Penguin Classics in a new translation by Siân Reynolds.

It is a good example of Simenon’s skill in describing not very much, whilst revealing an awful lot about his characters; in this case a mild-mannered bookseller and stamp collector of Russian-Jewish origin who has (he thinks) created a safe space for himself in the old market quarter of a small town in central France. When his wayward, much younger, wife disappears, he tells a small lie to cover up her suspected (actually well-known) infidelities, which proves to be the first crack in his supposedly secure humdrum life. The final outcome is as tragic as it is probably inevitable.

|

|

Books of the Month

When Beside the Syrian Sea, the debut novel of ‘James Woolf’ appeared in 2018, I wrote: from the start this has a ring of truth to the plot, tradecraft and setting (Ambler and Kim Philby country) and I suspect has been written by someone who has been there, done that and got the t-shirt, though of course never wears it.

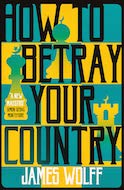

Now comes How To Betray Your Country [Bitter Lemon] and I am in danger of repeating myself, especially in the reference to the setting, Istanbul - classic Eric Ambler territory.

August Drummond is a spy on the edge of cracking up following the death of his wife. Thrown out of MI6 and heavily dependent on alcohol, he decamps to Istanbul and even before he gets off the aeroplane is embroiled in an ISIS-inspired plot which may be mercenary rather than ideological. The local MI6 officials, more concerned with office in-fighting than external threats, seem oblivious to any danger and only an intelligent Turkish intelligence officer (more shades of Ambler, though female this time) seems remotely capable.

The narrative unfolds in the third person, the first person and in extracts from documents and reports, which all point to the story being one long suicide note for the risk-addicted, much-troubled August Drummond who goes to his fate with aplomb.

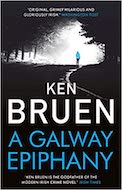

Anyone familiar with Ken Bruen’s series of novels featuring Jack Taylor over the past twenty years knows that Jack is no saint. In A Galway Epiphany [Head of Zeus] however, he is in danger of being mistaken for one, or at least a miracle if only by association. There again, it could all be a case of The Church’s insane determination to alienate all of the people all the time.

As you might gather, if you didn’t already know, Taylor has a healthy mistrust of organised religion, especially when organised by the Catholic Church and if he sends out an SOS he gets the Sisters of Solace. When Taylor is hit by a truck and spends weeks in a coma, his recovery may be miraculous, but was it a miracle? Does the Church want another shrine on its hands, or does it need one like Ireland needs another Eurovision win?

Taylor bludgeons and drinks his way through the conspiracies with his creator’s usual scatological running commentary on the current state of the worlds both temporal and spiritual. Along the way, the keen student of Irish pishogs (including what a pishog is) learns many a life lesson including how a statue of Saint Patrick has the power to deal out the final justice. This is Irish noir to the core and Ken Bruen, with his unique poetic style, is at its dark beating heart.

I cannot think of any crime novel centred on a Russian ballet company in London I have read other than Caryl Brahms and S.J. Simon’s 1937 comic classic A Bullet in the Ballet, until now.

Erin Kelly’s Watch Her Fall [Hodder] is anything but comedy-crime, emphasising the pain, dust, blood, sweat and paranoia of a ballet company and its egos, cocooned from the outside world, dedicated to giving the perfect (i.e. Russian) performance of Swan Lake. The early chapters, introducing the company and its ritualistic training regimes, which would surely put the SAS to shame, are not only fascinating, but educational, and at last I understood the plot of Swan Lake, which is just as well as the novel then gives us a mirror image of it as a noir crime story reminiscent of James M. Cain, which spins and twists faster than a turbo-charged fouetté.

Very well written, this is an impressive psychological thriller which confirmed this Philistine never to trust a black swan. Erin Kelly’s novel comes with a generous advance ‘blurb’ from novelist Charlotte Philby. Co-incidentally, the new paperback of Charlotte Philby’s A Double Life comes with a generous recommendation from....guess who?

For legal reasons I missed Alison Bruce’s new stand-alone The Moment Before Impact when first published last year, it is, however, now out in paperback [Constable] and I am glad it has caught up with me.

A horrific car accident (or was it?) involving a group of young students after a boozy picnic of the banks of the River Cam leaves Nicci Waldock, the driver, scarred in more ways than one. Three years and a prison sentence later, Nicci returns to her old stomping ground in Cambridge - not a part of the city familiar to tourists - and tries to pull together her life and her memory with the aid of a former journalist, only to discover things were not what they seemed.

The Moment Before Impact is an engrossing tale, sparingly but sympathetically told and Alison Bruce once again captures Cambridge the town rather than the gown brilliantly. She even manages a plug for Anglia Ruskin University (known as the College of Arts & Technology when I was there in the last century), where she now teaches creative writing.

Arthur Skelton is a barrister, he has a gloom-merchant of a legal clerk called Edgar, the year is 1929 and there’s a dismembered body in a suitcase in a quarry near Wakefield. That’s all you really need to know. Don’t bother trying to guess whodunit, just immerse yourself in the infectiously jovial atmosphere generated by David Stafford in Skelton’s Guide To Suitcase Murders [Allison & Busby].

It is the worlds which mild-mannered Skelton inhabits, both domestic and professional, which appeal here, often hilariously, from the highest law courts to his Yorkshire homeland to the epistolary contribution from Skelton’s cousin whilst on a religious mission to Scotland. There are some great gags at the expense of the Scots, the north/south divide (including a mention of a legendary Yorkshire figure called Joe Soap) and recalcitrant children, not to mention a cameo for an up-and-coming actor called Laurence Olivier.

Populated with a host of minor characters which could have stepped out of Wodehouse, you may not learn much about suitcase murders (though you might) but you will certainly find much to enjoy.

Just when you thought there couldn’t be any more twists on the classic American private eye tale, along comes Vera Kelly is not a Mystery [Verve Books] by Rosalie Knecht. The Vera Kelly of the title being a former lowly CIA agent who, on the day she loses her job and her girlfriend, reluctantly decides to become a private eye. She is by no means the first lesbian or gay fictional private eye, but having to live and operate in the New York of 1967-68 adds another layer of pressure, though it is not long before Vera is flying off to the Dominican Republic on the trail of a lost child.

In many ways, an imaginative riff on a familiar melody but one well worth listening to.

Legal Disclaimer

Two books which I fully expected to take pride of place in this month’s column, were the new novels by those firm favourites Lindsey Davis and Andrew Taylor: A Comedy of Terrors [Hodder] and The Royal Secret [HarperCollins] respectively.

For legal reasons - and for the second year running - I have not seen either prior to publication and thus am unable to provide any details. Given their provenance though, I can confidently say they will be pretty good.

Forthcoming

Richard Osman’s second crime novel will be The Man Who Died Twice and will be a follow-up to his hugely successful Thursday Murder Club.

As the book will not be published (by Viking) until September, and I know very few details, to go on about it would be pointless. Sorry about that; couldn’t resist.

Forthcoming 2

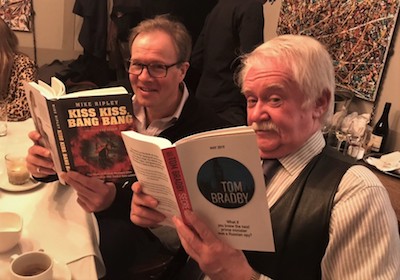

I am particularly looking forward (in fact I am reading it at the moment) to the new novel from ITN’s premier news anchor Tom Bradby, who gets an honourable mention in a well-known history of British thrillers in the period 1953-1976, despite not being born for much of it.

Triple Cross, to be published by Bantam on 13th May, is the third part of Tom’s trilogy of spy novels featuring Kate Henderson, now late of MI6 but still having to face up to the prospect that the Russians have infiltrated British Intelligence and are exercising undue influence in Downing Street. Given the cost of recent refurbishments there, I suppose we shouldn’t be surprised.

When Harry Met Agatha

I am delighted for my good friend Sheila Mitchell that her biography of her husband, the late Harry Keating, has been nominated for an Agatha Award at this year’s (sadly ‘virtual’) Malice Domestic convention in July.

Staycationing

As part of the government’s generously funded Track & Trace initiative, I have been asked to promote, given the current travel restrictions, the idea of vacations within the UK, ideally with a crime-fiction theme. I find that the ultra-prolific John Creasey was doing exactly that back in 1954.

‘The Toff’, aka upper-class sleuth Richard Rollison, was one of the many series heroes created by CWA-founder Creasey (1908-1973), who was to feature in 59 novels and two films. No wonder he needed a holiday.

Prediction

I now have the distinction, with the recent publication of Mr Campion’s Coven [Severn House], of having two novels published during lockdowns when bookshops and libraries were closed.

Another volume of my ‘continuations’ of the adventures of Margery Allingham’s famous detective, Mr Campion’s Wings, was scheduled for 2022 but there is a suggestion that UK publication may be brought forward to 31st October this year. Should this prove to be the case, I can confidently predict that the government will declare another lockdown on 30th October.

Sorry about that, but I will advise when the book can be pre-ordered so that you will have something to read.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|