| The Dark Side of Spying

I can’t quite remember how I first heard of the fictional spy Charlie Dark. It may have been a reference in one of Dan Fesperman’s excellent spy novels or a recommendation by my old friend Randall Masteller who curates the invaluable Spy Guys & Gals website. Either way, I am grateful to both of them for many things, especially the need to track down a copy of Checkpoint Charlie by one of my favourite American thriller writers, the late Brian Garfield (1931-2018).

It was not an easy book to find as I do not believe it was ever published in the UK and the only edition was the 1981 Mysterious Press one which I have finally acquired thanks to one of my bespoke book dealers. Checkpoint Charlie is not a novel, but a collection of twelve short stories originally written for publication in magazines between 1976 and 1979, which all feature the old, fat, badly-dressed and insubordinate CIA operative Charlie Dark. Charlie is, of course a brilliant agent, thanks to his quick-witted application of years of tradecraft, which is why he gets the difficult jobs, often those which have to be ‘off the books’, even though he declares himself to be inept with weapons and desperately avoids violence.

Dark’s missions take him all over the world, from California to Caracas, Finland to Africa, Australia, Hong Kong, Russia and Berlin (naturally) and, perhaps most unusual of all, the Aleutian Islands. Though this is perhaps not surprising given that Brian Garfield was, in 1969, the author of The 1000 Mile War, a history of World War II in the Alaskan and Aleutian Islands theatre of operations.

Charlie Dark is a wonderful creation, disgracefully little known over here, but then I have always felt that Brian Garfield - possibly best known for Death Wish, famously or infamously filmed by Michael Winner - has been much undervalued on this side of the Atlantic. After cutting his teeth on westerns, Garfield showed he was proficient at spy fiction (Hopscotch), crime fiction (Recoil), political thrillers (Line of Succession) and historical thrillers (Kolchak’s Gold). Always inventive and written in straightforward unaffected prose, anything by Brian Garfield spotted in a second-hand bookshop should be snapped up.

Antarcticana

After my ramblings last month about thrillers set in Antarctica, crime-writing supremo Peter Lovesey got in touch and insisted that I read Cold, Cold Heart by Christine Poulson, published by Lion Fiction in 2017, of which I had been shamefully ignorant.

As in last month’s The Dark, a young female scientist is sent as a replacement medical officer to an Antarctic research station where strange things start to happen as the darkness of a six-month winter descends. But in Cold, Cold Heart, a parallel mystery is unfolds around the disappearance of another scientist working on a breakthrough cancer cure back home in East Anglia, to which the only witness may be a very hungry cat.

Cold, Cold Heart is a smooth, well-crafted mystery and it is not giving anything away by pointing out that the main character, Katie Flanagan, survives the Antarctic darkness, as she reappears in An Air That Kills (2019) investigating a research project into a virus which may ‘jump species’ and result in a global flu pandemic. Now who could have thought that one up?

I was pleased that my mention of The White South provoked very positive messages from several readers declaring themselves, like me, to be fans of the work of Hammond Innes (1913-1998), who was, back in the 1950s, the one thriller writer Ian Fleming was anxious to outsell.

Innes cropped up in another rather surprising context in August, in The Times magazine in a feature on her new novel by actress Celia Imrie, surely a National Treasure in waiting.

In the context of male misbehaviour in showbusiness in the days before the #MeToo movement, the story is recounted of how she once stayed overnight at the home of ‘her widowed admirer’ the thriller writer Hammond Innes. Entering her room with a breakfast tray, Innes rested a hand on her breast. “I left it there,” was Imrie’s response. “Why not? The old boy was 80 and alone in the world.” (On his death, Innes bequeathed her his London home, according to the article.)

I met the charming Ms Imrie at the shiva held for our mutual friend Marcel Berlins and, having totally forgotten to commend her on her dramatic appearance in the early scenes of the cult movie Highlander, I then made a fool of myself by mishearing her when she said she was returning to America to star in a new series of a television drama. Thinking she had said Stranger Things, I professed to being a great fan only to realise, after some minutes of awkward silence, that Celia Imrie was in fact referring to the award-winning comedy series Better Things.

The last word on the subject (for now) goes to MacLehose Press who, this month, publish The Antarctica of Love by Swedish author Sara Stridsberg.

The novel, which involves the murder of a young woman has been described as ‘brutal and oddly full of light ...wild and violent’ but is not, as far as I know, set in Antarctica.

Every Day’s A Murder Day

No, not a valuable mis-printed edition of Richard Osman’s massive bestseller from last year. The Tuesday Club Murders is in fact a new edition of Agatha Christie’s The Thirteen Problems from 1932, under the title this anthology of cases for Miss Marple, was published in America.

The club in question, which meets on Tuesdays (the clue being in the title) is made up of amateur detectives tackling unsolved mysteries, though they don’t stay unsolved for long once Miss Marple has scrutinised them.

The idea of an informal dining club where members solve crime, or just generally exchange stories, is of course not restricted to the fiction of Dame Agatha, although Thursdays do seem more popular than Tuesdays. John Buchan, famous for his Rungates Club stories (1928) actually trailed the idea with a Thursday Club which featured in The Three Hostages in 1924 and later there actually was a Thursday Club, the late Duke of Edinburgh being a prominent member, which met in Wheeler’s restaurant in Soho.

In pale imitation, in the 1990s, there was another Thursday Club which met in The Three Tuns public house behind Portman Square, the brainchild of the late Bill Carmichael, the step-father of Pierce Brosnan, which attracted numerous celebrities and off-duty detectives based at the nearby police station. Many a crime writer also attended, some of whom are now quite famous and who have expensive lawyers. Therefore, I will say no more.

In Like Flynn, Again

Having, last year, republished the first twenty (of more than fifty) ‘Golden Age’ mysteries of Bryan Flynn (1885-1958), those tireless enthusiasts at Dean Street Press are now publishing books 21 to 30 in the Flynn canon, most if not all of which feature his amateur sleuth Anthony Bathurst.

The new titles are, in chronological order: Cold Evil, The Ebony Stag, Black Edged, The Case of the Faithful Heart, The Case of the Painted Ladies, They Never Came Back, Such Bright Disguises, Glittering Prizes, Reverse the Charges and The Grim Maiden. Originally published between 1938 and 1944, most of these titles have been vanishingly rare, at any price, for over half-a-century – until now.

Politics Today

Clearly there is not much going on in British politics these days, since Brexit got done; so it is no wonder that certain political figures have time on their hands to write their debut thrillers.

Alan Johnson, the former Labour MP and Home Secretary, is already the author of four best-selling volumes of autobiographical memoirs which have been universally described as ‘warm-hearted’ and that, I am afraid, is the problem with his first foray into crime fiction, The Late Train To Gypsy Hill [Wildfire].

The ‘hero’ of the book is mild-mannered, easily-embarrassed accounts clerk Gary Nelson (named after a member of Take That, as if life wasn’t already cruel) who lusts silently after a mysterious blonde on his commuter train. Gary’s life in London was perhaps less exciting than he had expected when moving to the big city from Aylesbury. He shares a house in Crystal Palace and the highlight of the week seems to be the ‘housemates’ meeting which, if quorate, takes decisions on whether or not to invest in a sink tidy. Until, that is, he finally makes contact with the blonde on the train, or rather she makes contact with him, as she is being threatened by two Moscow-trained hoods after the poisoning of a Russian dissident.

Our Gary helps the girl off the train at Gypsy Hill and they throw off their pursuers ‘walking through the streets of London SW1 scoffing pizza and ending [up] at the Premier Inn, Victoria’ where they spend the night together as Mr and Mrs Nelson, though we are reassured they slept in separate beds.

Railway stations and bridges feature again in the dramatic climax of the story as Russian gangsters and Scotland Yard’s finest collide, though I doubt very much that The Sun would have reported it as: In one dramatic showdown, heroic Detective Superintendent Louise Mangan, nabbed the Russkies responsible...

It is a rookie mistake in crime writing that a newspaper report always serves the plot rather than accurately reflects what a national newspaper - even The Sun - would, or even legally could, print (“nabbed” - perhaps; but “Russkies”???).

In contrast to Alan Johnson’s well-meaning though rather vanilla hero, the protagonist of political journalist Robert Peston’s The Whistle Blower [Zaffre] really is an unpleasant piece of work. Gil Peck is, not surprisingly, a financial journalist with impeccable political connections. He is also venal, selfish, arrogant, an appalling driver and certainly somewhere on the spectrum when not sorting cocaine. It’s a wonder anyone talks to him let alone trusts him with sensitive information, as his own definition of journalism is solely to upset people.

It is 1997 and an election is pending and so is a financial scandal involving pension funds if Gil Peck has anything to do with it, especially as his sister, a Treasury economist, has been killed in a cycling accident having started the financial hare running. Not that Gil Peck, initially, lets a little thing like his sister’s murder get in the way of a good story - as long as it’s his by-line.

Somebody once said that the best thrillers had a sympathetic hero who then had to be put through hell before triumphing. I’m afraid with Gil Peck, you just want to see him suffer, though The Whistle Blower does provide some interesting insights into the workings of Whitehall and there is great fun to be had putting real politicians’ faces to Peston’s 1997 characters.

Parisian Beat

It is rare that this column, or any other, can announce the arrival of a ‘new’ book by Georges Simenon (1903-1989), who was known to many in the world of crime fiction simply as ‘The Master’, and it might be pushing it, but I am assured that Death Threats [Penguin Classics] contains short stories never published in English before. That’s good enough for me.

Two of the five stories in Death Threats were written before WWII, three during it, though the war never seemed to impinge on the pipe-smoke wreathed contemplations of Inspector Maigret. All are classic examples of the genre which is uniquely Simenon.

I know from reader feedback when I mentioned the impressive job Penguin Classics are doing reissuing Simenon’s work, that new readers are continuously discovering Simenon. As a sampler, or an hors d'oeuvre, Death Threats is an ideal introduction to the world of Maigret.

Stark Reminder

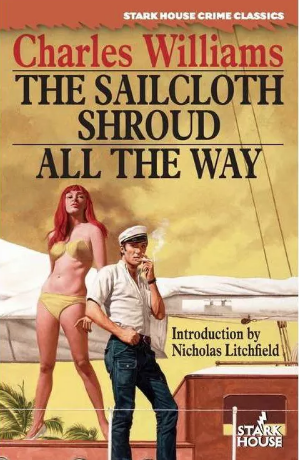

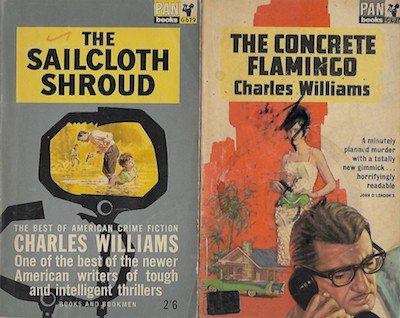

Once described as ‘the best kept secret in American pulp fiction’, Charles Williams (1909-1975) was a fabulous writer of hardboiled crime stories, often with a nautical theme. Although forgotten here, many of Williams’ thrillers were published in the UK in the 1960s and were successful as Pan paperbacks, alongside titles by John D. MacDonald and Ross Macdonald (no relation). But Williams’ novels seemed to disappear from both bookshops and memory, despite a spurt of interest when the Nicole Kidman/Sam Neill film of his book Dead Calm came out in 1989.

I’m delighted to say that the Charles Williams flag is still being flown from the mast-head of the inventive Stark House Press in America who have just published a double volume containing All The Way (1958) and The Sailcloth Shroud (1959), both of which I can recommend as excellent examples of American noir.

As their condition might suggest, my collection of Charles Williams’ thrillers was the result of many years scouring second-hand bookshops and jumble sales, slightly handicapped by buying (on more than one occasion) a book I already had under different title. For example, the Stark House edition of All The Way - the original title - was better known in the UK as The Concrete Flamingo.

Good News

In the depressing chaos of the current news cycle (Afghanistan, hurricanes, climate change, Covid and the unfortunate return of Norwich City to the Premiership), two flashes of good new to lighten the gloom.

Firstly, my Italian wine merchant, despite the restrictions on travel and the shortage of lorry drivers, has battled through and delivered the new vintage from Tuscany.

Secondly, my old friend Sheila Mitchell has won the 2021 Macavity Award for best critical/biographical work presented by Mystery Readers International, for H.R.F. Keating - A Life of Crime.

I will be celebrating the latter thanks to the former.

No Relation

I hear that American author Susanna Calkins has a new novel out, The Cry of the Hangman [Severn House], a historical mystery set in 17th century London featuring her series heroine, a printer’s apprentice, Lucy Campion.

I am fairly confident that this Lucy Campion is not a distant relative of a certain Albert Campion, who just happens to feature in a new novel next month, also from Severn House. Just thought I’d mention this.

|

|

Books of the Month

I have been informed, so far, of 50 new crime and thriller titles being published in September, which is more than one-and-a-half a day. Given the restrictions imposed by Covid, the number of publishers who have unfriended me, plus those who simply don’t bother telling anyone when a new book appears, fifty is the absolute minimum number of books to be published here for the first time this month. (I do not count reissues, paperback editions other than originals, e-book only or self-published.) Given all that, I will certainly have missed some interesting titles, for which I can only apologise, but I can say with certainty that the first three titles covered here will dominate the best-seller lists in the coming weeks.

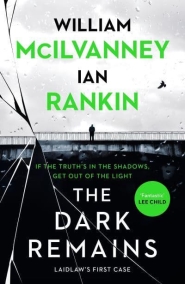

In the words of the late William McIlvanney, Jack Laidlaw was a man who ‘found himself doing penance for being him’ especially in Glasgow on a Friday night: ‘the city of the stare’. McIlvanney also called Ian Rankin’s creation John Rebus ‘the Edinburgh Laidlaw’, whereas Ian Rankin has a character tell Laidlaw: ‘Your head might be hard but your heart isn’t’.

In The Dark Remains [Canongate], Ian Rankin has written a prequel to McIlvanney’s ‘Laidlaw’ trilogy which broke the ground for the new wave of ‘Tartan Noir’ crime writers, based on notes left by McIlvanney after his death in 2015. So it’s not a ‘continuation’ novel, nor a completion and it is tempting to think this might be an homage to the writer who inspired him. Well, it probably is, and clearly it is a labour of love, as Rankin has had to exchange his Edinburgh for McIlvanney’s Glasgow, and set the novel in 1972, when Ian would have been still at school. Nonetheless, the Laidlaw gang’s all here - or should that be the gangs are all here as turf wars between gangster families simmer following the fatal stabbing of one firm’s dodgy lawyer.

Jack Laidlaw, a lowly Detective Constable at this point, and a ‘streetman’ in the sense that Davy Crockett was a ‘woodsman’, solves the murder and averts a gang war in his own forthright style, despite the incompetence of his police superiors and his ability to cite John Updike and W.H. Auden along the way. Rankin not only keeps faith with McIlvanney’s creation, but even adds a further nod of admiration by having ‘his’ Laidlaw quote an old school friend called ‘Tom Docherty’.

Is The Dark Remains merely a worthy homage to one of the godfathers of crime fiction - and not just of the Tartan variety? Well, yes, but there’s no ‘merely’ about it. Is it a good crime novel? Damn right it is.

It would take more than a global pandemic to stop there being an annual Dick Francis novel entirely, but it has managed to delay one. However, Iced [Simon & Schuster] by Felix Francis is now here, showing that he has a firm grasp on the reins of the family business.

Dick Francis brilliantly conveyed the dangers of horse-racing and the bone-crunching effects of coming off a horse at thirty-odd miles-an-hour. In Iced, his son now tells us how to risk life and limb at even greater speeds, plunging down the Cresta Run. The adrenalin-junkie hero of the novel is the son of a champion steeple chase jockey but has swapped the saddle for the toboggan yet cannot resist getting involved in the White Turf week-end in St Moritz, where horse-racing takes place on a frozen lake (just to increase the risk factor one presumes) and naturally there’s some chilly skull-duggery going on. [See reviews]

It would be churlish, not to say absolutely pointless, to condemn Richard Osman for repeating the winning formula of The Thursday Murder Club in his sequel, The Man Who Died Twice [Viking]. I mean which bit of ‘winning formula’ do you not understand?

The amateur sleuths of Cooper’s Chase retirement home are revving up their Zimmer frames for another case which duly comes along courtesy of a ghost from Elizabeth’s past and a missing cache of stolen diamonds. In other news, Joyce, waiting for something exciting to happen, has joined Instagram and Ibrahim has discovered an App which allows him to pay for car parking. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, it’s pointless going on. Just read and enjoy.

For most of its not inconsiderate length, Winter Counts [Simon & Schuster] by David Heska Wanbli Weiden reads like a blend of Tony Hillerman and James Crumley - two famous crime-writing names well worth dropping - but it is in the end its own unique creation.

Set on the Native American Rosebud reservation in South Dakota, Winter Counts - the title refers to the calendar system used by the Lakota Sioux (though they don’t like the term ‘Sioux’) - where Virgil Wounded Horse acts as the local enforcer to hand out two-fisted justice when the tribal police can’t and federal law enforcement won’t. When hard drugs start to appear on the reservation and his teenage nephew becomes unwittingly involved in the marketing activities of a Mexican cartel, Virgil determines to stop the trade before it gets a grip and along the way uncovers other crimes which exploit the already deprived inhabitants.

As a thriller it has its weaknesses, by turns overly sentimental and occasionally over-dramatic (does a gunshot really have to be spelled out as ‘BANG!’ in capital letters?) but as a novel which reflects the plight of a badly-treated people trying to hang on to its traditional beliefs, it is a thought-provoking account of a modern-day tragedy.

Velvet Was The Night [Jo Fletcher Books] by Silvia Moreno-Garcia is described by the author herself as ‘noir pulp fiction’ but I think it more than just a homage to the genre as it shows how the form can be used to deliver a political novel, and one which does not pull its punches.

Set in Mexico in the early 1970s, the two main protagonists of the novel are not themselves political animals. One is a day-dreaming, lovesick secretary in a dead-end job, the other a young hooligan and aspiring gangster and they find themselves unwitting foot soldiers in the country’s ‘Dirty War’ where a right-wing government determined to see Reds under every possible bed, deploys the police, the secret service and gangs of organised thugs known as Hawks, to harass and disrupt any and all left-leaning groups. Each of the lead characters is used as cannon-fodder and, linked only by their taste in music (at a time when music was repressed as well as political freedoms), employed separately in the search for a missing journalist, with violence dogging their every step, the only lesson to be learned being to trust no-one in authority. Can they survive, or do they face the ultimate result of noir fiction, which is the dark tunnel at the end of the light?

An assured piece of historical fiction, as well as a slice of noir, Velvet Was The Night sheds a dark light on a period of Mexico’s past which will not be forgotten, nor is likely to be forgiven.

Regular readers will know that I am unstinting in my admiration for good Scandinavian crime fiction, though I cannot claim anything like the expertise of Professor Barry Forshaw, who actually tours the London embassies of the Nordic nations as a guest lecturer, no doubt enjoying a roll-mop herring or two along the way.

However, a home-grown piece of ‘Nordic Noir’ has recently caught my eye, My Name Is Jensen [Muswell Press] by Heidi Amsinck, and it’s rather good. I say ‘home-grown’ because although set in Copenhagen (where somebody seems to be killing homeless people), author Heidi Amsinck is a journalist who has covered Britain and been a London correspondent for Danish newspapers and has had short stories adapted by BBC Radio 4.

Not surprisingly, her protagonist, Jensen, is a journalist having just returned to Copenhagen and literally stumbled over a murder. I believe Heidi Amsinck writes in English, so I cannot complain about dodgy translations nor that the author does not know about what she writes, for she clearly does and, impressively, in two languages.

Another female journalist, this time a naïve trainee fresh from an Oxford degree, features in The Man on Hackpen Hill [Head of Zeus] by J.S. Monroe, who as Jon Stock, has authored some impressive spy fiction in the past.

Bella, our ingénue journalist, dogged by concerns over a mentally ill(?) undergraduate friend, and DI Silas Hart of Swindon CID, find themselves investigating crop circles - something Wiltshire has a reputation for. The latest pair of elaborate circles are well worth the attention of the police as both have bodies at their centres; one a naked man, the other a woman in a straight-jacket as might have been used in mental hospital. In addition, the complex design of the crop circles depict mathematical formulae which may well be relevant to the work carried out at the secretive Porton Down research centre nearby. Naturally there are dark forces determined to stop Bella and Silas (and a rogue scientist) from getting anywhere near the truth.

Thriller writer Tom Bradby has described the book as ‘A kind of Wiltshire Da Vinci Code’ but don’t let that put you off. It’s really rather good.

To celebrate the 38th birthday (and why not?) of the Short Story Dagger awarded by the Crime Writers’ Association, the current CWA chair Maxim Jakubowski has done what he is famous for and edited an anthology of 19 winning stories in Daggers Drawn [Titan].

The bulk of the stories gathered here were written in the last ten years, but it’s good to see earlier contributions from such luminaries as Peter O’Donnell, Julian Rathbone and Larry Beinhart among the star-studded cast which features Ian Rankin, Jeffrey Deaver, Denise Mina and John Harvey. It is only sad that, for legal reasons, stories by Reginald Hill and Robert Barnard could not be included.

Reissue of the month without doubt is The Winteringham Mystery [Collins Crime Club] by Anthony Berkeley, which may have slipped the attention of some of my senior readers when it was first published in 1927 as Cicely Disappears under the pen-name A. Monmouth Platts. Prior to that it was a 30-part newspaper serial which offered substantial prizes if readers could guess the solution. A certain lady from Sunningdale in Berkshire, using her husband’s name, Colonel A. E. Christie, entered but her solution won only one of the £5 consolation prizes, which, if you think about it, is a stunning revelation. I mean, who knew Agatha Christie read the Daily Mirror?

Anything by Anthony Berkeley Cox (1893-1971), or ‘A.B. Cox’ or ‘Francis Iles’ or indeed ‘A. Monmouth Platts’, is well worth reading as, in the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of English detective fiction, he usually provided solid gold with innovative plots and at times a wonderful irreverence. I have read reports that he could be irascible, curmudgeonly and ‘gin-soaked’ but then he was for a time the crime fiction critic for the Daily Telegraph and, speaking from personal experience, those seem the ideal attributes for the job.

Good Reads? Good Grief!

My attention has been drawn to a website called Goodreads and a ‘review’ of Val McDermid’s new novel 1979 by someone called Barbara Fisher which, frankly, almost made me choke on my breakfast Sanatogen. I quote verbatim:

A novel without the Internet, where the characters “call on the telephone” rather than message via mobile, or send a letter rather than email is a distraction. To “get” the social, political, economic and technological setting of the 70s you’d have to have been born in 1961 to even have reached the tender age of 18 in 1979 - so we are looking at a current readership of a post aged 60 age group who could begin to find this era relatable. Of course age becomes irrelevant when looking at an era of more widespread interest historically e.g. World War One...But the 70s??!! Hardly an era of general fascination. And the IRA? When today’s terrorism is so very different? How many under 55s can relate to that? It’s a poor choice of era/setting for most to relate to I’m afraid.

As an over-55, who often calls people ‘on the telephone’ and who was a university student and then newspaper reporter in the 1970s - an era when clearly nothing of import happened because the Internet wasn’t there - and had first hand experience of the miners’ strike, too-close-for comfort encounters with two IRA bomb incidents and the terrorist attack on the Munich Olympic Village in 1972, I found myself speechless.

But I was not the only one to be outraged. A regular correspondent from North Wales, whose opinions I respect, expressed the following view: ‘The utter ignorance of how social past makes social present and social future is probably why we keep making the same fatal mistakes again and again, and people like Barbara Fisher get put in charge of a government's PR.’

I couldn’t have put it better.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster.

|