| First Blood

This month marks the 25th anniversary of the first (and only) First Blood Award made by a gang of renegade crime fiction reviewers with absolutely no connection to the Sylvester Stallone film of the same name. It was conceived, judged and actually awarded in a remarkable burst of frenetic activity, mostly co-ordinated on a mobile telephone (the size of a brick in those days) from the back of a black London cab.

It all came about because in 1993 the Crime Writers’ Association had refused to present their annual John Creasey Memorial Award for best first crime novel because none of the titles on the CWA’s short-list was deemed good enough. This despite the short-list having been made public, announcing the name of authors and titles not thought to be of sufficient quality to be so honoured, a salutary and humiliating experience to say the least. There was minor furore about this and the chairman of the judges, Bill Pardoe of the Birmingham Post, offered his resignation, which was not accepted.

In the Autumn of 1996, the CWA announced that again there would be no John Creasey Award as there were no first novels of sufficient quality around that year, though fortunately no short-list of ‘unsuitable’ candidates was published.

As this seemed a ridiculous dereliction of duty - one of the purposes of the Creasey Award surely being to help newcomers to the genre - a number of crime fiction reviewers were asked to nominate first novels from that year which could and should have been eligible. Very quickly it became clear there was no shortage of worthy candidates and a long list was whittled down to a short-list of six strong candidates. More phone calls to publishers insured that all the reviewers had copies of all six books, some rapid reading took place and it was decided, after all that work, to select a winner and actually make an award, if the CWA wasn’t prepared to.

Those renegade reviewers were: Marcel Berlins (The Times), Frances Fyfield (Mail On Sunday), Maxim Jakubowski (Time Out), Val McDermid (Manchester Evening News). Philip Oakes (Literary Review), John Williams (GQ Magazine) and myself (Daily Telegraph). And the authors on our short list were Christopher Brookmyre, Ken Bruen, Gerry Byrne, Manda Scott, John Fullerton and Margaret Murphy, most of whom seem to have done quite well in subsequent years.

Maxim Jakubowski allowed us the use of his Murder One bookshop for the actual presentation, which was made by Minette Walters, who had won the John Creasey in 1992 (and a Gold Dagger in 1994), and Christopher Brookmyre was the recipient.

Sadly, I was unable to attend the ceremony as I was in Milan on business, but thanks to a very expensive phone call from a hotel room, Maxim Jakubowski provided a detailed account of how things had gone.

I realise that I have now taken the name of my old chumette Minette Walters in vain two months running, without mentioning her new novel, The Swift and the Harrier which is published by Allen & Unwin this month.

Some years ago Minette moved away from the Dark Side of crime writing and into historical fiction set in the wonderful county of Dorset, or perhaps I should say Dorsetshire as it was known in 1642 when The Swift and the Harrier is set. The year is significant, as I am sure readers of this column know, as it saw the opening shots of the English Civil War (entirely caused by the introduction of a tax on beer, according to an old brewer I once knew) and much of the action takes place during the siege of Lyme Regis, a conflict I was shamefully ill-informed about, until now.

I Hear of Crime Writers Everywhere

I try and make it a rule that every fifth book I read is non-fiction, partly to keep the little grey cells active by taking a break from crime fiction. It is, however, proving almost impossible to get away from the genre completely.

In a recent foray into military history, I was fascinated by Carlo D’Este’s comprehensive account of the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943, Bitter Victory. Now being Sicily and the legend that Lucky Luciano and the New York Mafia helped in planning the campaign (a legend dealt with by D’Este in an appendix to the book), I might have expected a hint of crime/thriller fiction to creep in to the narrative. After all, Jack Higgins had got a book out of it with Luciano’s Luck in 1981.

What did surprise me, though, was that in describing the role of airborne troops in the invasion, one of the sources consulted by Carlo D’Este was The Red Beret by Hilary St George Saunders.

Regular readers of this column with good memories and too much time on their hands, will instantly recognise the name Hilary St George Saunders (1898-1951) as one half, with John Palmer, of the writing partnership which was Francis Beeding, the author some well-known detective novels and a host of mostly-forgotten thrillers which were hugely successful in the 1930s.

Saunders served in both world wars, winning the Military Cross in the first as an infantry officer and being on the staff of Lord Mountbatten in the second. The Red Beret was his history of the British parachute regiment and formed the basis of the 1953 film Paratrooper (aka The Red Beret), an early partnership between director Terence Young and producer Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli who went on to make Dr No.

Reading Bitter Victory and the account of the campaign around Mount Etna (it was near there that General Patton infamously slapped a shell-shocked soldier), I could not help remembering my personal ascent to the summit of the volcano three years ago, aided only by a Sicilian chauffeuse, a cable car and a Mercedes moon buggy whilst drawing courage from several of the fiery liqueurs brewed on its slopes.

At the time, Etna, which is constantly active, was merely warm to the touch, but I understand it has been flexing its muscles this year. In fact, from recent news footage, it is clear to me that something has awoken the dragon which lives in it.

What the Papers Said

On Saturday 9th October, it was a good morning for crime fiction fans who were reading the Times or the Daily Telegraph over their breakfast kedgeree.

In that once-great newspaper the Telegraph, the always-great Jake Kerridge revelled in the new, but sadly posthumous, Andrea Camilleri novel Riccardino, which is now published by Mantle, but for legal reasons I have not seen one.

This twenty-eighth and final Inspector Montalbano story has, it seems, Camilleri in playful mood, mischievously having his main character aware that his earlier cases have been turned into a television series (with a handsome young actor) and being interrupted by telephone calls from a sinister figure known as ‘The Author’. (I know several young Italian crime writers who have met Camilleri, who all described the experience as slightly sinister, as well as awesome.)

In the Times, television critic Hugo Rifkind had a go at Murder Island, the Channel 4 reality show where members of the public play competitive homicide detectives and try to solve the murder of a young woman in a wild and lonely Scottish location which bears an uncanny resemblance to Father Ted’s Craggy Island. The plot of the murder story is by Ian Rankin, who Rifkind rightly describes as ‘the master of getting Scottish people to kill each other for interesting reasons’, but how much better it would have been if John Rebus had been doing the detecting rather than stumbling civilians (muggles?) who just wanted to be on the telly. The focus of the show quickly becomes which of the rather irritating couples participating you want to see eliminated, rather than why the victim was murdered and by whom.

The same newspaper’s regular My Culture Fix feature was filled by Lee Child, who reveals that his favourite film is David Fincher’s Se7en, the box set he’s hooked on is New Tricks, thinks that Dreda Say Mitchell is ‘Britain’s finest crime writer’ and that he’s seen the stage show of Mama Mia eight times - but thought the movie version was pants.

And to mark the posthumous publication of John Le Carré’s final novel Silverview (which for legal reasons...), the Times’ thriller reviewer James Owen surveys ten possible successors including usual suspects Mick Herron, Charles Cumming and Joseph Kanon, my personal tip for future fame James Wolff and one author I was disgracefully unaware of, Lawrence Osborne (probably for legal reasons again). Surprisingly there was no mention in the feature of John Lawton, Robert Littell or Alan Furst.

The Ripster Rides Out

I have long had an interest in groups of fans - sometimes individual readers - who keep the flame burning for long, often unjustly, forgotten authors. In this way I have increased my knowledge and appreciation of Ian Fleming, Victor Canning, Dorothy L. Sayers, Desmond Bagley, Leslie Charteris, Francis Durbridge, Alistair MacLean and, above all, Margery Allingham.

So I was delighted to be invited to take part in the 14th Dennis Wheatley Convention which, sadly, had to be held over an erratic ‘Zoom’ connection.

The convention opened in the traditional manner ( I learned) when the agenda for the day was produced from Dennis Wheatley’s actual briefcase and topics covered included Wheatley’s ‘Library of the Occult’ imprint, a group book review of Unholy Crusade, a discussion on what audience Wheatley was writing for and a section where delegates recalled the first Wheatley novel they read, usually at an unsuitably early age. Despite the restrictions of Zoom, everything went swimmingly until one disruptive newcomer to the proceedings introduced an unscheduled discussion on Mayhem in Greece, clearly one of Wheatley’s most controversial books...

Southern Hemisphere Connections

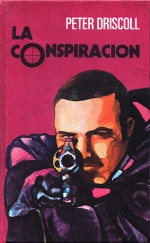

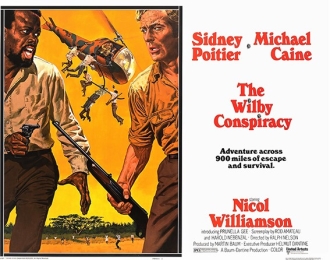

My South American correspondent, who curates the excellent website Una Plaga de espias, recently brought to my attention the Argentinian edition of Peter Driscoll’s The Wilby Conspiracy which was first published in 1973 and quickly filmed starring Michel Caine and Sidney Poitier.

To be honest, if I had not recognised the name of the author on that Argentinian edition, I would have been hard-pressed to identify the book, which I really should do as I edited a new edition in 2018.

The Wilby Conspiracy is probably the best-known thriller by Driscoll (1942-2005), drawn from his experiences as a journalist in South Africa and provided an early reference to Robben Island and its black activist prisoners - mostly famously, Nelson Mandela - one of whom escapes and goes on the run aided (reluctantly at first) by a white mining engineer. The novel charts the long pursuit of the pair across South Africa and in particular over the semi-desert known as the High Karoo.

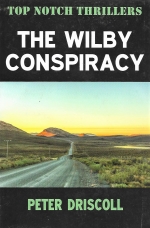

In need of a cover illustration for the reissue as a Top Notch Thriller, I contacted South African crime-writing supremo Deon Meyer, knowing him to be an expert photographer and a fanatical motor-cyclist. Deon kindly saddled up and rode out on to the High Karoo to photograph the road, near the town of Loxton, which the fugitives took in the book.

TBR or FGRT?

I have no idea where the expression ‘TBR’ came from but most readers of crime fiction are familiar with the concept of a To Be Read pile of books and indeed most readers have one - at least one.

For the purposes of this column, my personal TBR pile (actually a box or small crate rather than a pile) is organised, though I use the term loosely, on a monthly basis. Far less ‘organised’ and considerably larger is my FGRT - Finally Got Round To - pile of books by authors I have been meaning to try or re-read for many years. I know I am not alone in having a FGRT pile, or gravity-defying tower, but when I do finally get around to taking a book from it and discover that it had been worth the wait, it is a cause for celebration.

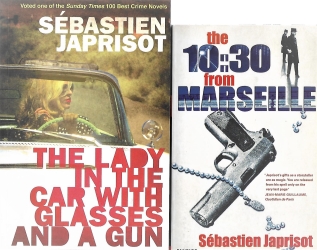

Of course, one reaction is ‘why did I not get around to this author before now?’ and that usually involves tracking down further books by that author and so the pile renews itself and never actually shrinks. This is exactly what has happened with French thriller-writer Sébastian Japrisot when I FGRT reading his 1962 novel The 10:30 From Marseille, a wonderfully-constructed murder mystery.

Japrisot (1931-2003) was a prize-winning author, translator (of J. D. Salinger), and film director. He also wrote the screenplay for the film The Story of O which I thought was a documentary on the application of the Arabic term Zero by the Pisan mathematician Fibonacci, until I discovered that it wasn’t...

Having arrived very late at the Sébastian Japrisot appreciation party, I immediately sought out his most famous thriller, the brilliantly-titled The Lady In The Car With Glasses And A Gun from 1966 and discovered that Gallic Books of London had produced a new edition in 2019 though that had somehow passed me by. First published in English in 1967, the novel won a ‘Best Foreign’ dagger from the Crime Writers’ Association in 1968, the first translated novel, I think, to be so honoured as previous ‘foreign’ awards had been given to Americans.

|

|

Books of the Month

Anyone suffering withdrawal symptoms from the ending of that most excellent French police drama Spiral (and who isn’t?) should rush out and get acquainted with the work of Olivier Norek, a former Paris policeman and scriptwriter on the series. Turf Wars was published in France in 2013 but has now finally made it into English thanks to MacLehose Press, and forms the second volume of Norek’s prize-winning ‘Banlieues’ trilogy. The Banlieues are the modern suburbs of Paris where tourists, if they have any sense, rarely go.

Unforgiving tower blocks, teenage gangsters, a thriving drugs trade and corrupt politicians all have to be patrolled (reluctantly) and contained (barely) by various rival departments of the French police. A sadistic killing (or two, or three) is the opening shot in a turf war between drug dealers which soon escalates into full-blown riot and civil disorder where the police count themselves just lucky to get out alive.

This is tough stuff and not for the faint-hearted - or anyone with a cat and a microwave - but you will have to go a long way to find a better hard-boiled policier.

The Killing Hills [No Exit] by Chris Offutt takes the bare bones of the traditional hard-boiled American crime story and fleshes them with a layered account of life, death and what passes for family ‘honour’ in the backwoods Kentucky town of Rocksalt. It’s the sort of town where the garages sell tires (sic), petrol and Bibles because they will all ‘get you where you need to be.’

Faced with her first murder case, the local sheriff asks her brother, Mick Hardin, for help. Hardin not only knows the local woods, but is a CID agent in the US army, currently home on leave as his (estranged) wife is very pregnant. While his sister fends off local political interference, for which read ‘cover up,’ Hardin investigates the web of tribal loyalties which govern the isolated families who seem to take a perverse pride in poverty and deprivation - families with fourteen children brought up in a two-room shack - and their ability to hold a violent grudge for many generations. In fact, their ability to sustain a blood feud makes the average Sicilian vendetta look like an argument over a supermarket car parking spot. It is a place where the only booming industry is the importing of drugs and the only escape route is to move north to Detroit to work for gangsters, or join the army as Hardin did.

It is Hardin’s army training which helps him solve the murder, though it has also destroyed his marriage, and in the end it is his army home he returns to. This short, powerful novel evokes, above all else, a terrible sadness about life in the Kentucky hills and the awful inevitability of it all. Hardin’s wife is thought too young for a midlife crisis but they came early in the hills. Everything did - death, hardship and loss.

I don’t think that The Inheritance [Faber] by Australian Gabriel Bergmoser qualifies as ‘outback noir’ as most of the action takes place in Melbourne and its environs, but it is certainly noirish in the sense that nobody is going to come out of this well.

Maggie, daughter of an abusive ex-policeman father is lying low and off the grid (for good reason), concerned only with searching for her missing mother and not really worried about inheriting a secret hard drive from her late father. Unfortunately, others are very interested in it and after alienating a local gangster and then a whole squadron of violent bikers, not to mention a cabal of crooked cops, Maggie is determined to find the thing despite seemingly overwhelming odds. Fortunately, she is a resourceful - in the Jason Bourne sense - survivor and proves herself very handy with guns, letter-openers, machetes, a rounders’ bat, broken glass, rocks and fire and the violence escalates, to really ridiculous proportions resulting in a body count equivalent to Round One in Squid Game.

It is over-the-top and the grand finale has the feel of a bit of a plot afterthought, but the bloody and violent action never lets up.

Although it must be a quarter of a century ago, I remember telling an editor at Orion how much I had enjoyed a book (The Concrete Blonde) by an unknown, to me, American, called Michael Connelly. To my surprise, the editor said that it was such as shame that Americans ‘didn’t sell’ in the UK crime fiction market.

I am sure she was delighted to be proved wrong as Connelly has gone on to create several distinct series protagonists and sell over seventy-four million copies of his books worldwide. His latest is The Dark Hours [Orion] and it features a double-act of Connelly’s most famous creation, Harry Bosch, working in tandem with more recent arrival, LAPD detective Renée Ballard. It’s Connelly’s thirty-sixth novel and, like the other thirty-five, it is frighteningly good.

Connelly has won multiple awards; his books have been filmed and he has produced a hit television series from them. I think I hate him.

According to the Daily Mail (so it must be true) Dominic Nolan ‘is set to become Britain’s Michael Connelly’ yet his new novel Vine Street [Headline] reminds me more of the work of another American idol, James Ellroy, partly for the breadth of his story spanning nearly 600 pages, and partly for his diversions into visceral, staccato prose often resembling blank verse. Nolan is also, like Ellroy, not frightened to throw in the odd Hollywood name - in this case Tallulah Bankhead on fine, disreputable form.

Set in 1935 and around the legendary Vine Street (next to the Free Parking corner on my Monopoly board) police station, familiar to many upper-class miscreants from squiffy toffs in P.G. Wodehouse to the Marquis of Queensbury, most of the action takes place on the Soho patch of Vice detective Sergeant Leon Geats as he battles the local crime kings as well as his rivals in the Flying Squad. In among the wreaths of Woodbine smoke is the ever-present fear of white slavery, but with new twist: are the girls being trafficked in from Europe really plants by the German Abwehr? (It is 1935 after all).

The period detail seems all there, though I had to look up ‘High Top’ (an Austin taxi sometimes known as an ‘Upright Grand’), as Geats goes about his detecting with his own personal mantra of ‘kick-in doors, crack heads.’ An epic historical crime novel which, like its hero. pulls few punches.

The cover of Zoë Sharp’s new thriller The Last Time She Died [Bookouture] carries the strapline ‘Blake and Byron Thrillers: Book 1’ which could be seen as a bit of a spoiler, or at least a puzzle as the two characters in question seem, initially, an unlikely pairing. John Byron is a senior police detective currently not on active duty (for reasons which become clear), whereas ‘Blake’ is a young woman with a mysterious past who quickly shows her skill as a burglar and clearly has her own agenda when she reappears at the family home after being missing for ten years.

Missing, as a 15-year-old, but never reported missing by her MP father - not the only suspicious thing about him - Blake appears as if back from the dead at her unlamented father’s funeral. This is not a happy home-coming and Byron, on hand to help the local constabulary, is intrigued and then involved as crimes past and present come to light.

The Last Time She Died is a fluent, fast-paced crime thriller, sharply written (as one has to say about an author called Sharp) with several hairpin plot twists and leaves the reader keen to find out what ‘Book 2’ in the series will bring.

As if she didn’t have enough on her plate (without, rumour has it, her favourite gin-and-tonic these days), Her Majesty the Queen has been roped into crime fiction as a sort of regal Miss Marple and makes a second outing as a detective in A Three Dog Problem by S.J. Bennett [Zaffre].

The Queen has, obviously, some disadvantages when doing her secret sleuthing (in this case into a missing painting and a body in a swimming pool), as she is constantly under intense scrutiny from the media and dedicated ‘Royal Watchers.’ On the other hand, she can always call for back-up from the army, the navy and the air force as well as the police if things turn nasty.

But I suspect they will not be called upon as the blurb for the book says that it is ‘perfect for fans of Agatha Christie and The Crown’ and it probably does exactly what it says on the tin - sorry, cover.

Re-issue of the Month

Like Sandi Toksvig, I was too young to remember Nancy Spain (1917-1964) in her prime as a journalist and broadcaster and neither Sandi nor I were born when Spain was writing detective stories, several of which are now available again in Virago paperbacks.

I was aware of who Nancy Spain was, of course, and not just because of her reputation as a clever and funny journalist and ‘media personality’ before anyone thought up that particular job description, or for the fact that she wore ‘mannish clothing’ and although her lesbianism - as Sandi Toksvig writes in her introductions to the Virago re-issues - ‘was never openly discussed, she became a role model for many, with the closeted dyke feeling better just knowing Spain was in the public eye.’

It was while researching the work of Margery Allingham that I discovered that Nancy Spain had been a visitor to Margery’s Essex home in the early 1950s, almost certainly to persuade Margery to write for one of the magazines she worked for, though it possibly led to a rather surprising relationship with Margery’s husband, Youngman Carter.

At last I have the chance to read one of Spain’s irreverent detective novels, Cinderella Goes To The Morgue, which was first published in 1950, but has lost none of its sense of fun and farce as the annual Christmas pantomime at the Theatre Royal in Newchester (perhaps Spain’s home town of Newcastle) has a cast of music hall veterans and raving egomaniacs such as Hampton Court who has made a career out of playing ‘Buttons’ and who only talks about himself, but at least he knows something about that.

When a suspicious death removes one of the principals from the cast, Spain’s regular amateur sleuths Miriam Birdseye and Natasha Nevkorina (having solved a famous poisoning case at Radcliff Hall - geddit?) are on hand and both, fortunately have thespian credentials. Natasha in particular has a wonderful gift for surreal lines such as ‘A principal boy without a pantomime is like a man without a moustache.’ With little concern for their own safety, or their alcohol intake, the pair gloriously charge into the breach once more.

The Long and the Short

I was always told, when I started out, that crime-writers, however long their careers, should not expect to see more than one or possibly two anthologies of their short stories published as publishers and agents both claimed they were a ‘hard sell’ these days - but what do they know?

Still, it is a remarkable achievement for a crime-writer to be celebrating their sixth collection, though not surprising when that crime-writer is Peter Lovesey, who has been producing high-grade crime fiction for more than fifty years.

His new collection Reader I Buried Them will be published by Sphere in February 2022 and I am told, by one of my trusted moles, that there is a treat in there for fans of Ellery Queen.

Baffled

I am usually well aware of how I might have offended publishers and authors. Agents I do not worry about, following Raymond Chandler’s maxim that it’s enough you let them live.

Yet I am baffled as to what I could have done to upset Belinda Bauer - a crime writer whose work I have admired in the past - or her publisher for the first I knew of the existence of her latest novel Exit was not when it came out in February, but when I heard it serialised on Radio 4 in October. It sounded jolly good.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|