|

Deadly Pleasures Missed

The American magazine (I suppose I should say eZine these days) Deadly Pleasures always entertains and informs and its multiple contributors show no remorse when they ‘review to death’ (their words) new mysteries. It seems a popular technique as far as its readers go, though I have never been sure what those readers, mostly American, make of this august and upstanding column which is syndicated in each issue.

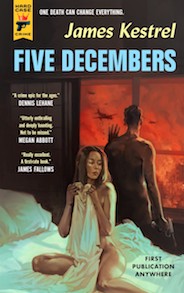

It is not uncommon for a new book to be reviewed more than once in Deadly Pleasures but I could not help but notice in the latest edition that one title was very favourably mentioned no less than four times. Five Decembers by James Kestel (a pseudonym), published by Hard Case Crime, is also the subject of a rave review on Steve Powell’s website The Venetian Vase, and Powell, a leading authority on the work of James Ellroy, is an academic whose views on, and reviews of, crime fiction I take seriously.

The book charts the hunt for a killer across south-east Asia in the months of November and December 1941 - so you can guess what’s coming - and has been described as a ‘terrific’ historical crime saga. Of course, for legal reasons, I have not actually read it, so I will just have to wait and see what Santa brings....

The Parties Over?

For a second year running there has been a dearth of the traditional publishing parties and book launches normally held in the run-up to Christmas. I am, however, pleased to report that at least one took place at Goldsboro Books in London’s humming and vibrant West End, though for legal reasons I was unable to attend.

The occasion was the launch of Tony Kent’s new thriller No Way To Die [Elliott & Thompson] which, although I’m told is just as exciting, should not be confused with the new James Bond film. That James Bond seems quite a character and I suspect we haven’t heard the last of him.

Royal Typo

The Review section of The Times on Saturday now carries a regular feature called ‘Rereading’ and last month it was turned over to thriller writer James Wolff who waxed lyrically over one of my favourite American crime writers, George V. Higgins and his 1970 debut novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle. I found myself in total agreement with everything Wolff wrote and, like him, I have an early paperback edition in my library, along with Cogan’s Trade and several other of his Boston based crime and legal thrillers (which were also pretty good).

Wolff’s analysis of Higgins’ talent is spot-on, as one might expect from the author of one of the spy thrillers of the year (How To Betray Your Country), but even he cannot explain why George V. Higgins is a far less well-known name than his contemporaries Robert B. Parker or Elmore Leonard, who, incidentally, was a big fan of Higgins.

My one claim to fame in terms of a connection with the hardboiled maestro Higgins, came more than thirty years ago when Lord Ted Willis, he of Dixon of Dock Green fame, reviewed my Angel Hunt for the Daily Telegraph and went generously over-the-top by suggesting I might be ‘mentioned in the same breath as George V. Higgins.’ It was, however, too good a quote not to put on the cover of the paperback.

Unfortunately, in the first draft design of that paperback cover, either the designer or a typesetter made a rather crucial mistake and the quote came out as ‘mentioned in the same breath as George V.’

Minefield

Unlike my colleague Professor Barry Forshaw, I have rarely been tempted to dip a toe into the world of academia on the subject of crime fiction, preferring to stick to my personal specialist subject areas: the wines of southern Tuscany, the military mistakes of Scipio Africanus, the wines of northern Tuscany and tegestology (look it up, it really is a thing).

I am convinced that it was a wise decision, especially these days, to stay out of the academic arena, despite being approached by an International Convention on Crime Fiction in a recent call for papers on the following thesis:

Crime as a social construct inhabits a liminal position. Like gender, it crosses boundaries and is thus positioned on a perpetual threshold between what is read as “order” or “normality” and “chaos” or “deviance.” Crime Fiction provides the space to investigate this liminality and to open up stereotypical concepts of normativity in crime, gender and sexuality. Crime Fiction’s relationship with sex and gender is thus fascinatingly complex and allows for a broad variety of critical angles on the topic.

Whilst this is clearly above my pay grade, I do hope Professor Forshaw will contribute a paper on the fascinating gender options offered in the works of the late, great Sarah Caudwell.

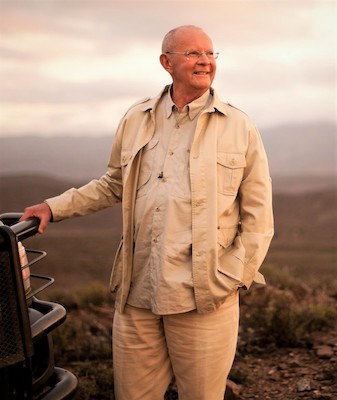

African Skies

Ten years ago I defended Wilbur Smith, who has died aged 88, from a ridiculous personal attack in the Daily Telegraph (a newspaper I had proudly written for in the last century) which made much of the fact that his fourth wife was forty years his junior and very little of his books

In rare public appearances (in this country) Smith made numerous remarks about the need for ‘real men’ in leadership roles and how he personally was proud of fathering numerous children ‘without ever having to change a nappy.’ All of which made Wilbur Smith the sort of guy I probably wouldn’t be happy having a pint down the local with, even if his ‘local’ did happen to be in the Maldives, and especially not having learned of the amount of ‘big game’ he had shot on safari (two elephants; lions and leopards too many to count).

But there is no denying that Wilbur Smith’s brand of Africa-based adventure fiction, openly influenced by Rider Haggard, had a tremendous impact on the British thriller scene in the 1960s and the reading habits since of many young males, who became loyal fans, not just here but across the world.

His books were tremendously popular in India - one fan announcing he was to be buried with his collection - and Italy, where he was given the Seal of the City of Milan in 2013. I long since stopped telling people, when visiting Italy, that I was a writer because I would immediately be asked if I knew Wilbur Smith and there was always such disappointment when I said I did not.

Spotted by The Spectator

My name has not often graced the pages of The Spectator, but when it has, the context has, so far, been quite flattering.

Recently, thriller-writer and former BBC reporter Peter Hanington wrote a piece on haikus and how the short, seventeen-syllable Japanese poetry form had kept him sane during various lockdowns and wormed their way into his fiction. Knowing that Ian Fleming (You Only Live Twice) had played with the haiku, he began to wonder if any other crime writers had included poetry and poets in their work, but it was not until he consulted that walking encyclopaedia of crime writing, Mike Ripley that he realised just how many had.

I was able to suggest a few authors and titles to Peter, not the least being P.D. James’ detective Adam Dalgliesh, who is currently experiencing a new lease of like thanks to the recent rather good Channel 5 TV series.

My Pun Is Quick

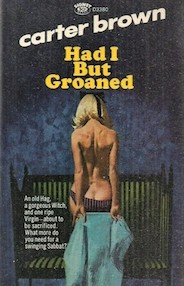

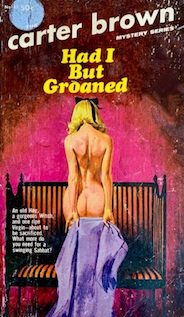

My Australian correspondent Jeff Popple has introduced me to one of the most unusual titles I have ever come across in crime fiction, Had I But Groaned by that prolific purveyor of pulp, ‘Carter Brown’ (a.k.a. Alan Geoffrey Yates, 1923-1985).

Said to have written up to twenty novels a year at his peak in the 1950s, and over 200 in total, Carter Brown’s books were popular worldwide and enjoyed a reputation for salaciousness and bad language in their time, and though those aspects would not raise eyebrows today, other aspects could well offend.

Certainly the covers of a Carter Brown book usually suggested something risqué and some covers were more risqué than others. When Had I But Groaned was published in 1968 the American and Australian covers were remarkably similar, but one was slightly more revealing than the other. Can you tell which was which?

|

|

Books of the Month

I can’t quite believe that it is now thirty years since I was introduced to a young American crime writer called Patricia Cornwell whose debut novel Postmortem introduced Dr Kay Scarpetta and a whole new sub-genre of forensic thrillers to the reading world.

In Autopsy [HarperCollins] Scarpetta is back on home turf, Virginia, where she was a pioneer as the first female chief medical examiner, although this time she is a White House appointee on the US government’s ‘Doomsday Commission.’ Yet not long into her new job she is involved in the case of a near-headless woman found on railway tracks and a catastrophe in a top secret lab in outer space, so it sounds like business as usual for the world renowned forensic pathologist, ably assisted by her psychologist husband, extended family and her ‘officious British secretary Maggie Cutbush, who speaks ‘in her lovely London accent.’

Any Francophile who has been unable to travel in the last eighteen months will either choke with envy and frustration or devour with gusto Bruno’s Challenge by Martin Walker [Quercus]. And I do mean devour, for this collection of short stories featuring Benoit ‘Bruno’ Courrèges, the police chief of the Dordogne village of St Denis, are less about crime but more concerned, delightfully, with food and drink, key concerns in a rural idyll which also enjoys horse-riding and rugby.

Bruno’s actual challenge involves cooking and the menu stretches from Kir Royal aperitifs through chicken with tarragon to strawberries in sweet wine, but food and cooking permeates all the stories, many of which centre on St Denis’ infant vineyards and attempts to launch its new wines. The whole collection is quite charming and heart-warming and there are nuggets of fascinating information, such as how many bubbles there are in a glass of champagne. (Fifty million it is claimed. I intend to check.)

There are shades of Line of Duty and echoes of The Usual Suspects in the new Simon Kernick thriller Good Cop, Bad Cop [Headline]. The cop in question starts off good, with the customary baggage of a broken relationship and (the latest thing) the loss of a child. He is ordered to go undercover and infiltrate a rogue band of right-wing vigilante cops who may be working for mysterious mastermind Kalian Roman, a sort of geo-political Kayser Soze.

Running with the bad cops, our good cop is involved in murders and cover-ups until he reverts to good cop (or does he?) during a terrorist attack on a restaurant resulting in multiple fatalities. Told in time-shifts across fourteen years, the good cop is forced to realise he has been a pawn in a game where the only thing which can be relied upon is the rising body-count.

The hero of The Lost by Simon Beckett [Orion] is also a policeman, this time a firearms officer, and has also lost a child - this time a young son who disappears from a playground in broad daylight.

Ten years later our hero gets a call out of the blue from a colleague he hasn’t seen since that loss and, unusually for an experienced firearms officer, he agrees to a midnight meeting without back-up, in a deserted warehouse on the spookily-named Slaughter Quay. The name should have been a clue; it was always going to lead to trouble.

It amazes me that such a nice chap as Jeffery Deaver can come up with such plots of twisty nastiness for his thrillers. Then I remember that Jeffery has degrees in both law and journalism and so has deep understanding of the world’s second and third oldest professions.

The Midnight Lock, his latest [HarperCollins] features his legendary hero Lincoln Rhyme and a worthy adversary in the form of a night stalker who can pick the locks on your apartment to gain entry and then lock up after he’s gone. How spooky is that? Well, that’s Deaver spooky, and when it comes to fast-paced serpentine thrillers, Deaver’s your guy.

It was, I suppose, inevitable that Holmes and Dracula would lock horns, or fangs, at some point but I never expected Drac to appear as a potential client, seeking the help of the famous consulting detective. Sherlock Holmes & Count Dracula by Christian Klaver [Titan] is, therefore, the ultimate ‘mash-up’ and I think the author had great fun writing it. Whether the Holmes purists, and they are legion, will have the same fun reading it is another matter.

A gruesome trail of severed finger(s) send Holmes and Watson to a spooky house in Kirby Cross in Essex and here the author displays his American roots. He could not, of course, as an American, be aware of local jokes that Kirby Cross, a suburb of Frinton-on-Sea, is probably just the place to find a vampire’s hide-out, but in telling Watson to join him there, Holmes sends a telegram instructing him to come to Kirby Cross ‘in Essex County.’

Books of the Year

It’s been a funny old year in many ways, but a good one for crime novels and thrillers; so much so it has been difficult to select one outright pick of the year, but I have, in S.A Cosby’s Razorblade Tears [Headline].

I had, however, so many other personal favourites in 2021 that I thought it worth listing them all, so - as they say on Strictly - in no particular order: Girl A by Abigail Dean [HarperCollins], Garden of Angels by David Hewson [Severn House], The April Dead by Alan Parks [Canongate], The Trawlerman by William Shaw [Riverrun], Kyiv by Graham Hurley [Head of Zeus], The Dark Remains by William McIlvanney and Ian Rankin [Canongate], The Killing Hills by Chris Offutt [No Exit] and Turf Wars by Olivier Norek [MacLehose].

And I haven’t even mentioned, though I will now, excellent spy thrillers by Tom Bradby, James Wolff, Paul Vidich, Dan Fesperman, Owen Matthew and Charles Cumming.

Reissue of the Year

Although not classed as a ‘thriller,’ The Passenger by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz [Pushkin Press] is hypnotically thrilling and also heart-wrenchingly sad. Written by a young German who had fled Nazi Germany and first published in 1939, it describes the mental implosion of a Jewish businessman’s attempts to leave Germany in the aftermath of Kristallnacht in 1938. Frightened and confused, Otto Silbermann evades the stormtroopers even as they are knocking on the door and leaving wife, home and business behind, embarks on a Kafkaesque series of train journeys looking for a way out. His paranoia increases as his attempts to leave the country are frustrated at every turn and his world, that of a good citizen who has paid his taxes and fought on the Western Front in World War I, crumbles around him. His one advantage is that he ‘doesn’t look Jewish’ which results in numerous interactions with his fellow citizens (by no means all fanatical Nazis) on his circular and increasingly futile train journeys. As madness descends, Silbermann is trapped like a hamster on a wheel in a cage topped with barbed wire.

First Book of the Year

I realise to my surprise that my career as an ‘influencer’ can now be said to have lasted thirty years, as it was in 1991 that I was first asked, by the Daily Telegraph, to nominate a (crime) Book of the Year.

My choice that year was Michael Dibdin’s Dirty Tricks, where he took a break from his series featuring Italian detective Aurelio Zen to write this excellent black comedy, savaging Oxford, Thatcherism and lots more.

Christmas Book of the Year

It has to be the new edition of Agatha Christie’s The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding [HarperCollins]. This ‘chef’s selection’ (Agatha’s description) of short stories, originally published in 1960 comes in a suitably seasonal hardback edition with festive endpapers.

The titular story also contains one of my favourite Christie lines, when Hercule Poirot is invited to spend a traditional Christmas in a fourteenth-century English country house. Even though there is a juicy mystery to tempt him, he is very reluctant to accept the invitation: He had suffered too often in the historic country houses of England.

Haven’t we all?

Non-Crime Book of the Year

In recent years I have been asked to recommend a favourite non-fiction read, if only to prove I am not a robot and can enjoy something other than crime fiction and thrillers.

Though to be fair, River Kings by Cat Jarman [William Collins] is both thrilling and something of a detective story as archaeologist Jarman follows clues from Repton in Derbyshire to the Ukraine and beyond on the fabled Silk Roads to chart an extensive Viking world of travel, trade (including slave trading), conquest and influence.

Until the New Year

(which simply has to be better).

Don’t forget to get boosted,

The Ripster.

|