|

Under The Influencer

I take my role as an influencer when it comes to crime and thriller fiction very seriously and feel genuine sympathy for the dozens of readers suffering from financial hardship having purchased books recommended in this column. Truly we are in a cost-of-reading crisis.

Occasionally I do get asked to provide bespoke reading lists or suggest titles from an author’s backlist. Often the request comes in the form of a plea: “I have read everything written by X, who should I try now?” In recent years, since his untimely death in 2018, the most common request I have received has been who can replace the late Philip Kerr?

Of course no one can, but what I think is behind the question is: I have read all Kerr’s Bernie Gunther books – what next? In which case, I have some suggestions for anyone who likes outstanding historical thrillers set in and around WWII where good men and women struggle to stay good in a mad, bad world. And right on cue this month comes Graham Hurley’s fantastic new novel Katastrophe [Head of Zeus].

Set in final months of the war, Katastrophe follows the fates of British and German characters established in previous novels. This does not mean the book cannot be read as a stand-alone, but I do urge anyone who will listen to read the entire six-volume series penned by Graham Hurley since 2016: Finisterre, Aurore, Estocada, Raid 42, Last Flight to Stalingrad, Kyiv and now Katastrophe, which has a former German spy and a journalist once a confident of Josef Goebbels both forced to work for new Russian masters in the ruins of Berlin, whilst straight-laced Scot and MI5 officer Tam Moncrieff is in Switzerland on a mission bound to be sabotaged by MI6 rival Kim Philby.

All are superb characters, their stories told in triple narrative streams, their joint aim is to see out the end of a catastrophic war where they have spent more time in infighting with their own side rather than tackling the enemy. Hurley’s series now goes under the collective title Spoils of War although it was originally called the Wars Within series which, in my (not so humble) opinion was the better description. To anyone who likes an immaculately-researched historical thriller (and the depth of Hurley’s research is breath-taking) which seamlessly blends fact and fiction, this series cannot be recommended too highly.

There are, however, two other series I would offer to the reader suffering from Gunther-withdrawal syndrome.

The Martin Bora series has been going for more than twenty years, though not all have been published in the UK -yet - by Bitter Lemon. Originally appearing in Italy the series by Ben (Verbena) Pastor, traces the aristocratic Martin von Bora’s military career from the Spanish civil war to (so far) the July Plot against Hitler in 1944. Where Bernie Gunther was a detective who often had to operate in a military context, the aristocratic Bora is a professional soldier who is forced, often reluctantly, to act as a detective.

Published, by Old Street, mainly between 2007 to 2013 (with a coda in 2021), the ‘Station’ series by David Downing are all named after Berlin (and Prague) railway stations: Zoo, Silesian, Stettin, Potsdam, Lehrter, Masaryk and Wedding. They feature Anglo-American journalist John Russell’s career, mostly in Berlin, in various years from 1933 to 1948. With his talents and contacts, it is hardly surprising that Russell gets recruited as a spy and thanks to many clever plot twists, he finds himself working for multiple intelligence networks and countries.

The Quill(er) is Mightier Than...

Recently a cabal of lovers of spy fiction held an internal discussion on which was their favourite ‘Quiller’ novel, referring of course to the series featuring secret agent Quiller who made his debut in Adam Hall’s 1965 thriller The Berlin Memorandum which quickly became The Quiller Memorandum when it was filmed. There were 19 Quiller novels in all, plus a lukewarm television series, until the author’s death in 1995, and I have no idea which title won that popularity contest among spy-fi fans, but for the record one of my favourites was Quiller’s Run from 1988, though all were rather good.

In considering the question, I began to realise what a prolific author, under a variety of pen-names, ‘Adam Hall’ was. When he published that first Quiller novel – which he admitted was inspired by the interest in spy fiction generated by The Spy Who Came in from the Cold – in 1965 as Adam Hall, he already had more than sixty novels under his belt, having started writing children’s stories whilst serving in the RAF during WWII. After experimenting with various pen-names, Trevor Dudley-Smith changed his name legally to his favourite one, Elleston Trevor, which he used as his main writing name for the bulk of his novels, many of which were filmed, including the bestselling The Flight of the Phoenix.

Among his now mostly forgotten pen-names, as Simon Rattray, he wrote a short series in the early fifties featuring the rich, eccentric private detective Hugo Bishop, whose passions were chess and his Siamese cat. All five novels had a chess piece in the title: Knight, Queen, Bishop (obviously), Pawn and Rook.

The Balance of Proof

The benefit of being sent an advance proof of a new novel to review is that, hopefully, one can read it and write about it on or around publication day, though having received 28 for July alone (plus a dozen actual finished copies of some titles), the sheer quantity of proofs can be overwhelming. The disadvantage of reading a proof is that when spotting something odd, one never knows – unless the publisher supplies one – if the oddity has made it into the published book.

Because I have seen only the proof and not the finished book, I will not name the impending ‘psychological thriller’ which contains the phrase (on page 179): I fished cock-handedly into my bag which I think should have been ‘cack-handedly’ but then again, I could be wrong.

All That Jazz?

Undertones by Nancy-Stephanie Stone [Galileo] is a book for people who like reading lists while listening to jazz. After a short potted history of jazz, the book lists crime novels in which jazz features, or at least is mentioned, and a further 200 pages is then taken up with lists of the authors and their books, a jazz discography, a chronology of those books, a list of locations of those books, the authors ‘hot one hundred’ list (of books, not tunes) and finally a list of ‘Jazz Books by Authors’. Not surprisingly, some authors end up with multiple mentions and though there is no index, a first impression would suggest that Brits John Harvey and Peter Morfoot come, quite rightly, high up in the most tagged list.

What is surprising is that the book comes blurbed by Barry Forshaw, no less, who calls it ‘assiduously researched,’ yet I could not see any mention in the European section of Django Reinhardt, Stephane Grappelli and the famous Hot Club and I would take issue with Bix Beiderbecke being described as a clarinet player, when in fact he was a noted cornetist. There is also no mention at all of Fitzroy Maclean Angel, the jazz trumpeter hero of a 15-book series of award-winning comic crime novels by someone whose name escapes me at the moment...

Golden Ageing

Publisher Galileo is also moving into the nostalgic ‘GA’ market with attractive new editions of mysteries by authors I had never heard of, though I am unashamed about that as one authority on the so-called ‘Golden Age’ has described one of them as ‘barely known’ although when I saw the title Midsummer Murder I did a double take and thought: surely not.

Old and infirm as I am, I had of course confused the book with the rather well-known long-running television show Midsomer Murders.(There cannot be many people left alive in Midsomer by now, can there?) Clifford Witting’s novel, featuring Inspector Harry Charlton (no, me neither) was first published in 1937 and takes place in the fictitious ‘Paulsfield’ which I believe is based on Petersfield in Hampshire. Witting (1907-1968) wrote 16 novels over 27 years, a quite gentle pace for a GA author.

Even less prolific as a writer of detective stories, though she also wrote ‘young girl’ novels, was Joan Coggan (1898-1980), who penned four mysteries in the 1940s featuring amateur sleuth Lady Lupin ‘Loops’ Hastings. Dancing With Death, from 1947, was the last of her frothy comic-crime capers to feature the ditsy, quite adorable Lady Lupin, the wife of the twice-her-age local vicar who often puts her well-shod foot in it socially and is delightfully scatter-brained.

The Social Whirl

Crime fiction parties are definitely back on the social agenda, even when – or perhaps exactly when – I am unable to attend. Fortunately, the editor of this august magazine {Ezine, you old fool – Ed.} Mike Stotter was present to represent Shots at the launch of Simon Toyne’s new thriller Dark Objects [HarperCollins].

And whilst it is a very long time since I was allowed near a Gala Dinner of the Crime Writer’ Association, Mike was on hand to congratulate Mike (yes, another one) Craven on winning this year’s CWA Ian Fleming Steel Dagger for thrillers with his Dead Ground [Constable].

Vintage Haul

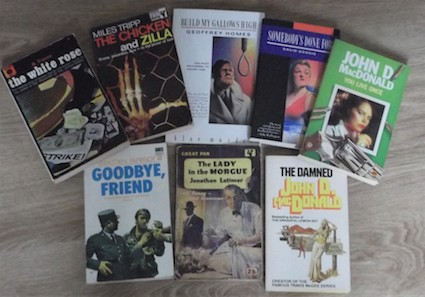

I have a bespoke second-hand book dealer who knows my tastes well and when the strain of wading through the tidal wave of advance proofs of new books gets too much, he supplies me with a selection of vintage paperback titles, a bit like a Red Cross parcel of pulp fiction.

A recent, much appreciated, parcel contained unread examples of work by authors known to me – notably the great John D. MacDonald, Miles Tripp. David Goodis. Jonathan Latimer and the mysterious ‘B. Traven’ as well as French crime-writer Sebastian Japrisot, whom I have discovered disgracefully late in life. The pick of the (very good) bunch though, was Build My Gallows High by Geoffrey Homes; a book and an author I had never read before.

First published in 1946, my edition dates from 1988 and was published in Simon & Schuster’s Blue Murder series, an imprint edited by Maxim Jakubowski, who was later to be co-editor with me on three Fresh Blood anthologies. But that is not my only personal connection with this classic piece of American noir.

In those pre-Internet days in the last century, I became pen-pals (you may have to Google that) with Philip Oakes, the long-standing crime fiction reviewer for the Literary Review. As well as being a journalist and poet of some distinction, Philip (1928-2005) was a man with a vast knowledge of jazz, crime fiction and film, and his autobiographical memoir From Middle England remains an absolute joy. One of his favourite film noirs was Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past, which was based on Build My Gallows High, and he would recommend it at every opportunity, flagging it up when it was due to be shown on television, which it is quite often, usually in the afternoon when a more discerning audience does not object to watching something in black-and-white. I have seen the film several times but never read, or actually ever seen, the book before.

‘Geoffrey Homes’ was the pen-name of Daniel Mainwaring (1902-1978) for crime novels written between 1936 and 1946 whilst working in Hollywood, first as a sound engineer and then as a studio public relations man. His most famous novel, Build My Gallows High, was also his last as he subsequently established himself as a prolific scriptwriter in television and on movies, including Invasion of the Body-Snatchers.

|

|

Books of the Month

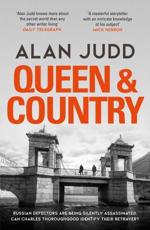

A spy, and a spy story, of the old school always find favour in this column and none more so than Charles Thoroughgood the hero of Alan Judd’s Queen & Country [Simon & Schuster].

Russian defectors hiding in secret locations in England are being ruthlessly knocked off by a new generation nerve agent, a sort of Novichok Plus, but how does the assassin know where to find them? Former head of MI6 Charles Thoroughgood is hauled out of retirement and sent into the field to find out, first into Russia and then Sweden, although it is the English home counties which prove the most dangerous place. Old school tradecraft and old school values of loyalty and honesty turn out to have value in the cynical world of modern espionage – and don’t anyone dare laugh at my Nokia ‘burner’ phone again.

Excellent characters, credible plot, fluent writing. I spy a great read.

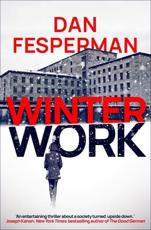

And then I spy another in Winter Work [Head of Zeus] by American spy-fi maestro Dan Fesperman.

Set in Berlin in 1990, a few months after the fall of the wall. The once-feared East German security service, the ‘Stasi,’ is in disarray but still holds sensitive information much sought after by both the Russians and the Americans. Senior Stasi officers, keeping their heads down, have to choose whether to ‘sell out,’ trust their Russian allies (although Russia itself is going through political change and it is a change frowned upon by a local KGB man called Putin!) or risk prosecution in a unified Germany.

Based on a real CIA operation where ex-Stasi officers were cold-called asking if they had any secrets for sale (!),Winter Work is an intelligent, atmospheric spy story perfectly conjuring up the final bad old days of the Cold War.

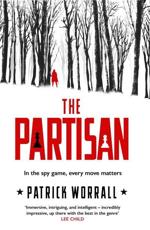

Certainly the most impressive debut thriller I have read this year, The Partisan [Bantam] by Patrick ‘Paddy’ Worrall is set in 1961 at the height of the Cold War but with frighteningly good flashbacks to the second world war in Lithuania and back stories set during the Russian (1920) and Spanish (1938) civil wars. There are also flash-forwards, so the narrative requires concentration, and the cast of characters is large, although thoroughly well-orchestrated. Centrally, the plot revolves around a pair of star-crossed young lovers, one English, one Russian, both chess-playing prodigies and both with family connections to their country’s intelligence services, who become entangled in thwarting a Kremlin plot to expand the Soviet empire into Western Europe.

Spies from both sides, sometimes seeming to change sides, become involved but always in the background is the partisan of the title, an exceptional character who breathes conviction into the description ‘avenging angel,’ with her own ruthless agenda.

Oliver Harris’ maverick cop Nick Belsey has done a bunk, given it all up and jumped on a plane to Mexico at the start of A Season In Exile [Little,Brown]. Quite why, I am not initially sure, not having read of his previous escapades and for a while it seems as if he is using Malcolm Lowry’s Under The Volcano as a guide book. After committing several minor crimes, getting drunk, getting high, drunk again, then robbed, our penniless hero ends up working a beachside bar where he comes to the attention of local hardmen working for a seriously big drug cartel which has come up with a novel method of shipping vast quantities of cocaine to Europe. Belsey falls suspiciously quickly into bed with the cartel and seems to be spearheading their export drive into England.

Or so it appears, but back in the UK, former colleague DI Kirsty Craik is convinced Belsey is being set up and pretty soon she is too and there’s a police interview scene worthy of Line of Duty. The violent action spreads to Belgium and the streets of London as double-cross follows double-cross, with armed gangs and armed police confronting each other at Christmas market where the present under the tree might be a hundred kilos of cocaine. The FBI also has skin in the game and there’s a wonderful description of the interior of the new American Embassy as ‘stylishly bland, like a Starbucks with ambitions.’

A Season In Exile is a breathless thriller which tears along dragging with it a reluctant hero who, amazingly, lives to fight another day thanks in no small part to the truly heroic efforts of the female police detective who believes in him.

From one breathless thriller to one which rips up all the speed limits completely. Total Control [HQ] by Alex Shaw features ex-SAS soldier turned MI6 agent Jack Tate up against a global conspiracy in which the violent action roams from America to Germany to the jungles of Myanmar, via London, Singapore and, to catch its breath, a rather sedate Brighton.

When a brilliant cyber terrorist hacks two billion dollars out of the bank accounts of Chinese criminal triad gangs, there’s bound to be trouble. When the funds appear to be heading for North Korea, it could be the start of a war and prove the old adage that political assassinations are easy but regime change might take a few days longer.

The empty Western Australian desert is most certainly an unhealthy place for two young females in a stolen truck on the run from the scene of a violent death, with a bag full of stolen gold pursued by one or more ruthless killers, so No Country For Girls [Sphere] lives up to its title and Emma Styles is to be lauded for an exceptional debut crime novel.

Alternately narrated mainly by the two mis-matched girls working in uneasy alliance to make their getaway from their respective pursuers, the story doesn’t shirk from the hardships facing them both from the landscape and their pasts and is salted with wonderful Australianisms such as: She’s driving like an old woman, like there’s a Violet Crumble up her arse.

Naive and blissfully innocent in many things, the two protagonists, Charlie and Nao, have glaring flaws but you cannot help hoping they survive the perils which face them. They make Thelma and Louise look like characters from an Enid Blyton story.

Any master-spy who lives to see retirement is lucky; to retire to Venice and a career as a professional art restorer is bliss, and in the bosom of a loving family, this is exactly what Gabriel Allon, formerly of Israeli intelligence, faces. It is not long, though, before an old contact in the art world tempts him with a mystery about the attribution (possibly a 17th century Van Dyck) of a painting and Allon is back employing all his skills as one of the ‘espiocrats’ – a lovely word – of the spy world.

Portrait of an Unknown Woman [HarperCollins] by Daniel Silva is the latest outing for Gabriel Allon, one of the most popular heroes on the spy-fi scene, which takes him, not altogether reluctantly, to France, London and America and into a conspiracy involving hedge-fund finances and the fine art world. Fortunately, Allon has not lost his old skills and can still defend himself when attacked in a Venetian alley by using his training in Krava Maga, the Israeli Defence Force’s own brand of martial arts, at which Gal Gadot (Wonder Woman) is proficient. It is easy to become jealous of Gabriel Allon in his eminently civilised retirement, though I am rather surprised he chose a Brunello where the traditional accompaniment to osso bucco is surely a Barolo or an Amarone.

Unreliable narrators are fairly common in crime fiction these days, but the narrator of All I Said Was True [Raven] by Imran Mahmood is unreliable and unstable from the off, which isn’t surprising as she has just been found blood-red handed (literally) nursing the corpse of a murdered woman she claims never to have seen before.

Our narrator, who is a lawyer (of sorts) is being questioned by police and deliberately withholds information from them (and the reader) in order to see out the 48-hour detention rule, though quite what is supposed to happen then is unclear. The story revealed in flashback includes multiple examples of the female protagonist’s fragile mental state including an estranged mother, a missing father, a husband she suspects of having an affair, a mysterious stranger who may be a guardian angel or a stalker, an obsession with an expensive marble kitchen work top, a rather vague sub-plot involving industrial espionage and a lot of references to knives.

The narrative voice is, at times, florid to the point of overkill: ‘A ribbon from a pipe organ slipped out between the closed church doors;’ visiting a pub she ‘walked into a vale of hot ale;’ ‘But that’s how he was, a whorl of sunlit life;’ and ‘The room makes a sound likea katana pulled from its saya.’

The nub of a good thriller, somebody once said, is to create a sympathetic character and then put them through hell. When the hell seems to be mostly of their own making, the reader’s sympathy tends to slip away, but those who want a mystery of the how-on-Earth-does-she-get-out-of-this? school will devour this in one gulp.

One of the main mysteries of The Whisperer’s Game [Little, Brown] by Italian Donato Carrisi is not who is the serial-killer (or proxy serial-killer) being hunted here, but where is this story meant to be happening? There is a city and a countryside with a lake, but no specific places; countries or currencies are not named, although distances are measured in kilometres and there is a Federal Police Department, so at least Brexiteers can sleep soundly.

Characters have names suggesting a variety of nationalities – Bauer, Shutton, Berish, Delacroix, Karl and Frida Anderson – and the lead investigator, Mila Vasquez, has the (hopefully) unusual trait of carrying a fresh razor blade in her handbag in case she feels the need to self-harm. All this adds to the generally bleak dystopian atmosphere and somehow lowers the tension level because the whole world portrayed is unreal, especially the behaviour of Mila Vasquez which at times require a suspension bridge of disbelief.

However I did learn (though I had to look it up) what a Howavart was thanks to a character called Hitch, a big, friendly retired police dog, and I will look out for the breed at next year’s Crufts.

Advance Warning of Service Disruption

Please note that there will be no Getting Away With Murder in September, although all normal Shots services continue unabated. I will be away, officiating at the annual Chianti Crime Festival, which this year is launched under the banner Bullets In Bologna, followed by a research project in Meiringen in the Bernese Oberland, at a venue which I understand offers spectacular views over a nearby waterfall.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|