|

A Bridge Not Far Enough

Most visitors to Florence make a bee-line for the Ponte Vecchio, the city’s iconic bridge over the River Arno and the lucky ones cross it via the secretive Vasari corridor whilst the majority of tourists amble across the bridge itself gawping at the bling offered by the jewellers who occupy the shops there, though very few seem to purchase anything.

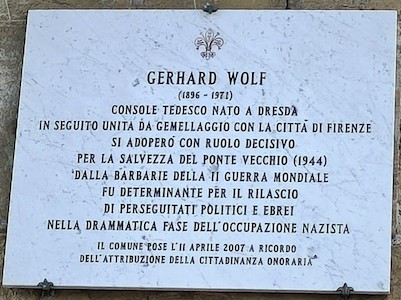

Halfway along the bridge there is an inscribed stone plaque which has always fascinated me since I first spotted it and was convinced that here was the seed of a screenplay I could pitch to Steven Spielberg should I ever run into him

The memorial stone, placed in 2007 by the city authorities honours Gerhardt Wolf, the German Consul in Florence during WWII who played a ‘decisive role in the salvation of the Ponte Vecchio’ in 1944, about whom I realised I knew next to nothing although I was aware of the rough outlines of the bridge’s story.

With the German army retreating to defensive positions north of Florence, a British army Corps (with Indian and South African troops in the vanguard) advancing from the south, American bombers attacking from above and Italian partisans active in the surrounding hills, there were genuine fears that the historic city might be completely destroyed. Of strategic importance were five bridges over the Arno, the most famous being the Ponte Vecchio with its medieval lining of shops, although the nearby Ponte Santa Trinita was thought by many to be of more architectural and historic importance, and as they prepared to depart, German troops mined them all.

On a night in August 1944, the bridges were systematically blown up, one after the other, but not the Ponte Vecchio – said to be Hitler’s favourite bridge. How did the Ponte Vecchio survive? Did Italian partisans disable the charges placed under the bridge? Did the explosives fail to go off? Did Dr Wolf, the German Consul, even though he was not in the city at the time, somehow intervene and prevent the destruction? Surely there was the making of a good movie here.

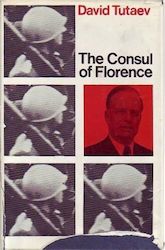

After a long search, I found a book, The Consul of Florence written by David Tutaev in 1966 which I thought I might be able to use (or steal from) as a basis for my pitch to Mr Spielberg.

Sadly it was not to be as the book, for all its interesting sidelights on Italy during the war, simply lacks any sense of tension or excitement when it comes to the fate of the bridges of Florence. Perhaps I was expecting too much, possibly something like Is Paris Burning? (the film of which was scripted by Gore Vidal). I’m still convinced, though, that there’s a good movie in this story somewhere.

Private Eyes I Have Known

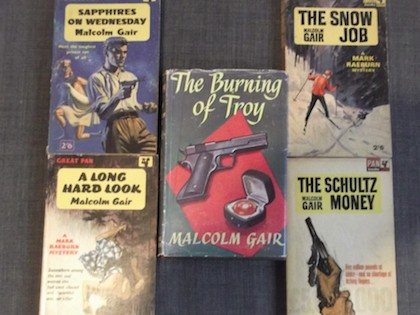

If I asked you to name a fictional private eye popular in the 1950s, I’m guessing Philip Marlowe, Lew Archer and maybe even Mike Hammer might be mentioned, but Mark Raeburn? I don’t think so, except by me.

I have recently completed my collection of novels featuring Mark Raeburn (though not the short stories) with the acquisition of The Burning of Troy after a long search, one of five thrillers written between 1957 and 1961 by ‘Malcolm Gair’. Raeburn was that unusual beast – a British (proud Scot actually) private eye – and has more or less been forgotten, as has his creator, though goodness knows why.

Malcolm Gair was the pen-name of John Dick Scott (1917-1980) who served in the Ministry of Aircraft Production during WWII and in 1944 joined the Cabinet Office as an official war historian. After the war he wrote novels under his own name and became literary editor of The Spectator. He adopted the Gair name for his thriller writing, most of his output featuring the astute and resourceful Mark Raeburn, who has a side interest in jewellery.

Which is handy as The Burning of Troy of the title of my latest acquisition is a fabled, flame-coloured opal, missing since supposedly being given to Josephine by Napoleon, but now rumoured to have been found somewhere in Europe. Hired by some fabulously wealthy ‘celebs’ as we would say today (and slyly satirised here), the case gives Raeburn the chance to enjoy first class trips to France and Venice and has the use of a driver, a Rolls Royce and private aeroplane, at one point flying in to a quaint little Italian airfield at Treviso, which in those pre-Ryanair days probably was quaint. Along the way he meets a blithe psychopath and there is the inevitable final shoot-out.

Although it would certainly have been judged as tame when compared to Dr No which was published the same year, The Burning of Troy - and all the Raeburn novels – offers a fast-moving, cleanly-written crime story with a likeable hero. I am so glad I finally, more than fifty-five years after first reading one, completed the casebook of private eye Mark Raeburn.

Bouncing Czech

Having mentioned, last month, four excellent thrillers set in Czechoslovakia, along comes a fifth, but I was wrong to get my hopes up. Czech Point by Nichol Fleming (1939-1995), nephew of Ian, was published in 1970 and features Billy Lester, an advertising copywriter who gets sucked into rescuing a Czech dissident (and skiing champion) from the clutches of the dastardly Russian invaders.

Unsurprisingly, Lester turns out to be a keen skier (and there’s a lot of skiing detail in the opening chapter) which is how he gets involved in the plot, following a lead to Vienna and then, with suitable romantic interest on board, to Prague. That Billy is an amateur at the cloak-and-dagger business is never in doubt; that he’s also a bit of a twit soon becomes clear.

For a start, he is obsessed with a legendary hero of thriller fiction. No, not his Uncle Ian’s creation, but an earlier incarnation, Bulldog Drummond; and I do mean obsessed. There are constant ‘What would Drummond do?’ asides in the first-person narrative. I counted nineteen instances before I gave up in despair. He also refers, as I am told Bulldog Drummond did, to the main female character as a ‘topping filly’ and at one point informs the reader ‘I’ve never been averse to necking’, which gives a flavour of how childish the writing can be at times. Other examples include ‘Crumbs!’ being the nearest we get to a swear word; a plot twist being described as ‘a brainy wheeze’; and, on seeing a border fence, the exclamation that this must be ‘The Iron Curtain!’

Essentially, Czech Point is an escape story, a run from Prague to the West by car, truck, horse, train and eventually driving a jeep through an electrified fence, though not, oddly, on skis. Perhaps they should have waited for winter. Lester’s credibility as a man of action does not age well given that his choice of car, which he raves about constantly, is a Ford Cortina which impresses the poor Czechs and gobsmacks the Russians as much as, say, an Aston Martin DB5 would have – but no, I mustn’t go there...

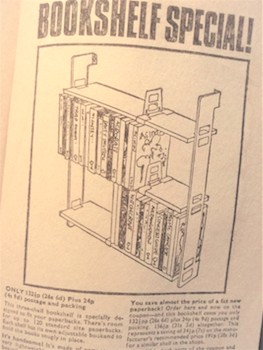

It is churlish to say that the most interesting thing about my 1971 Sphere paperback edition is the advert in the end papers, but it is one I’ve never seen before.

Readers are offered what every reader needs: more shelf space. A three-shelf self-assembly bookshelf capable of holding 120 mass market paperbacks could be yours for the rather curious price of 132½p plus 24p postage and packing (or, as the advert explains, 26 shillings and sixpence plus 4 shillings and ninepence).

As I am no economist, I have no idea how the cost of an Ikea Billy bookcase compares, but a shelving for 120 paperbacks for less than two quid back in 1971 sounds like it was a good deal I missed.

A Gentle Spy (Story)

I am a big fan of Alan Judd’s recent spy fiction, but it was only after chancing on the 2016 film The Exception, did I realise it was based on a 2003 novel by him, The Kaiser’s Last Kiss.

It is a short, really quite romantic spy story set in Holland in the early days of WWII, centred on the household of the exiled Kaiser Wilhelm II, which may be unwittingly harbouring a British spy. It is a clever, nuanced novel, particularly when the ageing Kaiser meets the new German regime in the form of Heinrich Himmler and the old king has to balance a possible return to position (if not power) against his ingrained, iron-hard snobbery. I recommend it highly and fail to understand how I missed it when it first appeared.

'Tis the Season to be John D.

I no longer expect to receive Christmas cards from publishers, having been ‘cancelled’ (as I believe the young people say) by so many these days, but I did think one or two might have sent me notice of their December crime fiction titles. But no, not a one.

Fortunately I have a contingency plan for my December reading needs (once the World Cup comes home that is) thanks to the services of my bespoke second-hand book dealer and will be feasting on a batch of vintage paperbacks by that old master, John D. MacDonald.

It was more than forty years ago when a fellow commuter into London, Jonathan ‘Lovejoy’ Gash, insisted that I really must discover John D.’s work. I did, and never looked back. Today I think I have more MacDonald titles in my library than any other author and that’s not counting Philip Macdonald or Ross Macdonald, two other firm favourites.

Late As Usual

I admit to being slow on the uptake in many things these day, so it will come as no surprise to hear that I have only just discovered how good the German television series Babylon Berlin is, a mere four years since Ali Karim, with Labrador puppy enthusiasm, recommended it most highly to me.

Based on the novels of Volker Kutscher, the series (four seasons so far) follows the multiple cases, criminal and political, of policeman Gereon Rath, and quite spectacularly so in one of the most impressive recreations of the Berlin of 1929-1931 I have ever seen.

There are five novels translated into English in the Inspector Rath series and a sixth, Lunapark, has been published in Germany but I cannot find if and when an English edition will appear.

Long Service Medals

If I could give out Long Service Medals I would, but I can’t so all I can do is give honourable mentions to two innocent ‘civilians’ who have survived the maelstrom of crime fiction.

The first is my Australian chum Jeff Popple, who this year celebrated 40 years as a reviewer, whose first review – of Ted Allbeury’s The Secret Whispers, appeared in the Canberra Times in 1982. Undaunted, Jeff continues to review for numerous publications and as Mr Campion’s Mosaic was one of his picks of 2022, it is clear that he is a man of great wisdom and taste.

I would award a personal medal to the long-suffering Fiona Messenger of North Wales (code-named Mrs Trellis) who in her 15th year as the sub-editor of this noble column. Yes, Getting Away With Murder really is sub-edited. Mostly for points of grammer and speling though rarely taste, with all the mistakes added later by a team of highly-paid typesetters and hot metal press operators.

Coming To A Bookshop Near You

As is traditional, I will be listing my fictional picks of the year, but to whet the appetite and strain the credit cards, here are a few books to look forward to in 2023.

Veteran thriller writer Gerald Seymour gives us the third instalment of his latest spy series with In At the Kill [Hodder] and veteran crime writer Peter Lovesey brings us another Peter Diamond mystery, Showstopper [Sphere], both in January. In April, former foreign correspondent Alan Philps tells the story of the Moscow hotel where Stalin billeted (and watched like a hawk) all the foreign journalists during WWII in The Red Hotel [Headline], out in April. And coinciding with CrimeFest in May, comes Moscow Exile [Grove Atlantic] by John Lawton, for which I am already saving pennies in a swear jar.

Re-Read of the Year

Whenever I get depressed at the state, or volume, of today’s output of crimefiction, which is increasingly often now I am of great age and approaching peak curmudgeon, I instinctively turn to one of the old masters when it comes to story- telling and reach for an ancient paperback by Hammond Innes or Nevil Shute or, especially, Eric Ambler.

Journey into Fear, set in the early days of WWII before Italy joined in, follows the sea journey from Istanbul to Genoa of an innocent British engineer unwittingly carrying information which the enemy wants to prevent getting to England. It is a wonderful thriller, showing Ambler’s skill at describing places and shady characters with great economy, as an ‘ordinary’ hero struggles to control his fear when he finds himself totally out of his comfort zone, alone and threatened by ruthless professionals. A masterclass.

Non-Fiction Read of the Year

Marc Morris’ The Anglo-Saxons [Hutchinson] might look daunting but it is a very readable narrative history of that period of history long dismissed as the ‘Dark Ages’ once you have sorted out your Aethelreds from you’re Aelfleads and your Cnuts from your Harthacnuts.

Don’t be put off and, thanks to the lavish illustrations in the hardback edition, you will discover that the period (the bit between Romans and Normans, which usually gets ignored in schools) is far from dark and, for devotees of thrillers, packed with intrigue, power struggles and back-stabbing – literally in some cases.

|

|

Books of the Year 2022

It has been a good year for thrillers and difficult to select an outright favourite so I have picked a round dozen and, as they say on Strictly, in no particular order, here are my favourites of 2022.

I would recommend Graham Hurley’s Katastrophe [Head of Zeus] with only one reservation, that it is a far more satisfying book if read immediately after reading the other five novels in Hurley’s quite magnificent ‘Wars Within’ series. The blend of fact and fiction is seamless across multiple narrative streams as WWII comes to an end, with the protagonists, British and German, often fighting their own side rather than the enemy. An outstanding achievement.

Tom Bradby’s superb spy thriller Yesterday’s Spy [Bantam] is set in 1953 and there is a KGB mole inside the British secret service (when is there not?) betraying operations in the Balkans resulting in dozens of deaths. I know what you’re thinking, but it’s not that straightforward. Maverick agent Harry Tower, both suspicious of and suspected by just about everybody, has to contend with the ongoing mole hunt whilst trying to find his estranged left-wing journalist son who has gone missing in Tehran, just as Iran is in political turmoil and, being oil-rich, a country of considerable interest to the major powers, who are not averse to backing a coup or perhaps a counter-coup. To cut through the political chaos and find his son, whose investigative journalism may have uncovered some unpalatable truths, Harry resorts to violence, at which he is remarkably good.

Another ‘historic’ spy story, this time from American spy-fi maestro Dan Fesperman was Winter Work [Head of Zeus]. Set in Berlin in 1990, a few months after the fall of the wall. The once-feared East German security service, the ‘Stasi,’ is in disarray but still holds sensitive information much sought after by both the Russians and the Americans. Senior Stasi officers, keeping their heads down, have to choose whether to ‘sell out,’ trust their Russian allies (although Russia itself is going through political change and it is a change frowned upon by a local KGB man called Putin!) or risk prosecution in a unified Germany. Based on a real CIA operation where ex-Stasi officers were cold-called asking if they had any secrets for sale (!), Winter Work is an intelligent, atmospheric spy story perfectly conjuring up the final bad old days of the Cold War.

William Shaw, writing as G.W. Shaw, came up with a rip-roaring seaborne adventure, Dead Rich [riverrun] which is absolutely terrific. A Russian oligarch falls out of favour with the Kremlin and flees with his family to the safety of his luxury super yacht currently moored in the Caribbean. The oligarch’s paranoia about personal security is well-founded because somebody is clearly out to get him along with the yacht’s crew and the rather timid British musician who has been dragged along by accident. Suspicions grow and no-one seems to be trustworthy, so perhaps being out on the high seas is the safest place to be; but that is exactly where all hell breaks loose and this being the Caribbean, all collateral damage can of course be blamed on pirates.

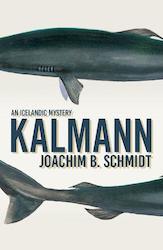

Clearly not getting enough snow and ice in his native Switzerland, in 2007 Joachim B. Schmidt made the logical choice to emigrate to Iceland, the setting for his new novel Kalmann [Bitter Lemon]. Apart from a stand-out cover showing a Greenland shark (pertinent to the plot), this Icelandic mystery features one of the most unusual protagonists in crime fiction. Kalmann is a 33-year-old shark fisherman and Arctic fox hunter living a solitary life in a small, run down coastal village, where the locals tolerate his eccentricities and think him essentially harmless, even when he dons a cowboy hat, a tin star, toy gun and holster, and proclaims himself town sheriff. A weird and oddly wonderful hero in a slightly weird but never uninteresting novel.

Staying with crime in a cold climate, Jo Spain’s excellent The Last To Disappear [Quercus] is set in a fancy Lapland resort in Finland which offers skimobile rides, sleigh rides, ice skating, ski-ing and other far more chilling activities in a small town called Koppe, which, under the surface is far from a Christmas wonderland. When a young British girl working in the resort goes missing and turns up murdered, her estranged brother turns up in Finland seeking answers, discovers that his sister is not the first young woman to go missing in Koppe in recent years and teams up with a brave, if inexperienced local policewoman (a wonderful character) to finally sorts things out.

May God Forgive [Canongate] by Alan Parks is crime fiction which pulls no punches and is the fifth outing for 1970’s Glasgow cop Harry McCoy, who will surely be one day ranked alongside Laidlaw and Rebus in the hallowed halls of Tartan Noir; a tough, old school copper up against everything his particular urban jungle can throw at him – and then some. Stunningly good.

Charlotte Philby, and quite honestly I can’t think who else could have written it better, tells the story of Edith Tudor-Hart and her connection to the ‘Cambridge ring’ of spies, the most famous of which was her grandfather Kim Philby, in Edith and Kim [Borough Press]. With a liberal sprinkling of extracts from SIS security reports (genuine ones as far as I can tell) and letters from Kim Philby in exile in Moscow, she constructs a Rubik’s cube of fiction around the real lives of a network of spies which, born out of anti-fascist beliefs in pre-war Vienna, showed a dogged faith in Stalin’s NKVD (and its dubious track record) as it infiltrated British industry and the intelligence hierarchy. A tour-de-force.

The Matchmaker by Paul Vidich [No Exit Press] is a stone cold, stone brilliant, Cold War spy thriller of the old school set in Berlin in 1989 as the Wall between East and West comes down. The CIA are hunting a Stasi spymaster known as The Matchmaker due his establishment of a network of ‘Romeo’ agents who seduce and marry vulnerable women in the West, thus providing them with a cover for their activities. What neither the Stasi nor the CIA have reckoned with, however, is the reaction of one of ‘Juliets’ when she realises she has been duped into a sham marriage and has her own score to settle with The Matchmaker. Scenes of Berlin street-life at the end of the punk era, the actual crumbling of the wall and the subsequent ransacking of personal files in the hastily-abandoned Stasi headquarters, are brilliantly evoked and Vidich even gives us a grieving woman at a graveside and a musician who played the zither in a nod to The Third Man, making The Matchmaker a book crying out to be filmed – but only in black-and-white.

Queen High [Quercus] by C.J. Carey is a fascinating and suspenseful novel of alternative female history set in a 1955 where Britain is a client kingdom of Nazi Germany. Or rather queendom as it is Queen Wallis, widow of Edward VIII, who sits on the puppet throne. In the caste system imposed on women by the Nazi Alliance, the lead character is in danger of slipping into the spinster category and being exiled to a ‘Widowland’ but before then has to combine her job as a censor of ‘degenerate’ (i.e. anything non-Nazi, especially Jane Austen) novels and poetry, in order to interview Queen Wallis to discover whether she is still towing the party line. To complicate matters, there’s a senior, but very dead, SS officer sitting on a bench in St James’ Park. Gripping, devilishly imaginative and far too plausible for comfort.

In Ashes In The Snow [Harper Collins], Italian crime writer Oriana Ramunno poses the question: where would a detective find a murderer in Auschwitz in the winter of 1943? The cynical answer, of course, is just about anywhere, especially when the victim is an SS doctor involved in horrific medical experiments and the nearest thing to an eyewitness is a young boy, a twin, who has been ‘selected’ by the notorious Dr Josef Mengele. Not surprisingly, the detective involved is changed by what he discovers there and his behaviour becomes somewhat irrational – as it would, given the circumstances – but there is no doubting the power of the story and the righteous anger of its telling.

My fun read of the year was, without doubt, the wartime thriller Basil’s War [Head of Zeus] by Stephen Hunter writing with tongue firmly in cheek. Our hero - and what a hero! - is Basil St. Florian, an outstanding British agent selected for an impossible mission in between bouts of love-making with his mistress, Vivien Leigh (whilst Laurence Olivier is in Ireland scouting locations for Henry V) by the Special Operations Executive in order to find the key to a code which ‘Professor’ Alan Turing of Bletchley Park cannot crack. This requires Basil to be dropped into occupied France, make his way to Paris and infiltrate the library of the Institute de France to find and photograph an 18th century manuscript with the Gestapo and the Abwehr hot on his trail. Basil St Florian may not be a prototype James Bond, but he certainly could be the secret agent Ian Fleming fantasised about being.

Missed Books of the Year

There were no doubt dozens of new thrillers I should have read in 2022 but I was particularly irked to have missed, for a variety of reasons, the following: The Medici Murders by David Hewson, Act of Oblivion by Robert Harris, Berlin Exchange by Joseph Kanon and Ian Rankin’s A Heart Full of Headstones.

Best Blurb Ever

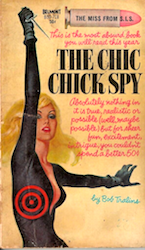

To get flavour of what a book is about, the innocent reader relies heavily on the cover and any ‘blurb’ contributed by the publisher. Until now I was unaware of the work of American Bob Tralins (1926-2010), who wrote more than 250 mystery and science fiction novels, but I much admire for its honest blurbage, his 1966 thriller The Chic Chick Spy.

The blurb states unequivocally that: This is the most absurd book you will read this year.... Absolutely nothing in it is true, realistic or possible (well, maybe possible) but for sheer fun, excitement, intrigue, you couldn’t spend a better 50 cents.

Night Lights

The ground staff here at Ripster Hall have come up with an alterative to the traditional Christmas tree this year, by illuminating the trees in the grounds to produce a stunningly colourful display.

But having seen my projected energy bill (does Octopus have the same logo as SPECTRE?) this display will be limited to the period midnight on Christmas Eve to five-minutes into Christmas Day.

Ding Dong Merrily

(Leslie Phillips, RIP),

The Ripster.

|