Party Time

I have only just recovered from the hectic Macmillan Crime Party held at Goldsboro Books in London’s Cecil Court, the absolute go-to venue for publishing parties these days. Distracted only by the gloriously book-lined shelves and an abundance of alcohol, I was able to meet several authors for the first time and before they realised who I was and could escape.

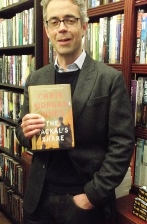

I have to admit to being slightly embarrassed to meet Chris Morgan Jones as, for legal reasons, I had not read his new thriller The Jackal’s Share, but it soon emerged that we shared a joint admiration for the work of Eric Ambler, which nicely broke the ice.

It was good to put faces to the dust-jacket names of William Ryan and Jessie Keane. William’s third Russian thriller The Twelfth Department appeared last month whereas Jessie’s eighth (I think) novel, Ruthless, appears in July.

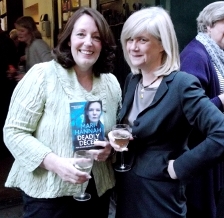

And it was a delight to finally meet the charming Mari Hannah, author of Deadly Deceit, even if under the strict supervision of Macmillan publicity supremo Philippa McEwan.

Street Party

I hope the staff of Goldsboro Books have allowed themselves enough recovery time before they host the annual Crime In The Court event on 4th July in Cecil Court in London’s West End, an event which is already firmly established as the hot ticket on the crime writing social calendar. Further details can be found on http://www.crimeinthecourt.com/ but for the uninitiated, this is a splendidly informal assembly of writers, publishers, agents and readers which rapidly turns from a serious debate on crime fiction into a street party! Not to be missed.

Centenary

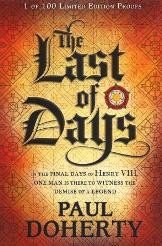

As learning about dastardly deeds within the Tudor court has never seemed more popular, it is fitting that history-mystery maestro Paul Doherty should set his one hundredth (yes, one hundredth) novel around the death bed confession of King Henry  VIII, though it is not a confession to a priest and in The Last of Days [published by Headline this month] few characters get to die peacefully in bed. VIII, though it is not a confession to a priest and in The Last of Days [published by Headline this month] few characters get to die peacefully in bed.

Set during the winter of 1546-47, the reader is never left in doubt that Doherty knows his stuff when it comes to Tudor in-fighting and politics, just as he has proved over the last 27 years (and perhaps six pen-names) that he knows his medieval history and has passed on his enthusiasm for it to millions of readers. I suspect the most common compliment Paul Doherty receives is along the lines of ‘If only I had been taught history like that at school’, which is something he should be very proud of.

Grand Master

Congratulations are in order for my dear friend Margaret Maron, who was recently made a Grand Master of the Mystery Writers of America, and not before time in my not-so-humble opinion.

The creator of two superb mystery series with female protagonists – New York cop Sigrid Harald and North Carolina judge Deborah Knott – and also a tireless campaigner for the mystery genre, Margaret has the distinction of being the person who inducted me into the Sisters In Crime organisation many years ago. Clearly she has now been forgiven…

Lost in Translation

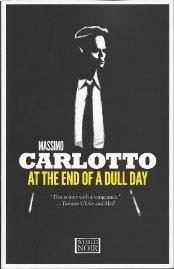

I was looking forward to discovering the work of Italian crime writer Massimo Carlotto in the very attractive World Noir imprint of Europa Editions’ version of At the End of a Dull Day.

A member of the ‘Mediterranean noir’ school, Carlotto describes that school’s philosophy as ‘telling big stories …that denounce what is wrong but at the same time posit the culture of solidarity as an alternative to that of greed and violence’. Well, I’m afraid I’m not convinced by that mission statement (or just don’t understand it) when it comes to At the End of a Dull Day as the main protagonist is a greedy, psychopathic control-freak who kills casually, tortures women and sells them into slavery without a qualm. The ‘big’ background story is, I suppose, corruption and sex in Italian politics, yet the ‘hero’ here, former terrorist Georgio Pellegrini now supposedly going straight, seems to be a holy mile away from providing any sort of viable alternative to that world. In fact compared to what Pellegrini puts his women through, a Berlusconi bunga-bunga party seems positively civilised.

Things aren’t helped by the translation, which is distinctly odd in parts. Whenever she misbehaves – or just he feels like it – Pellegrini makes his wife straddle a ‘spinning cycle’ and pedal furiously. At first I thought I was having a flashback to a perfectly horrible scene in a Derek Raymond novel over 20 years ago, but gradually I realised that what was involved was an exercise bike. In other places, a political party gets a ‘tanning’ in the elections where I think the word should be ‘drubbing’; the waiters in a restaurant are referred to as ‘waitstaff’; the hero ‘goggles’ something on the internet rather than Googles; a character says, with a straight face ‘Ah, the ripening maturity of my gerontophilia’; a political fixer is known as a ‘vote bundler’; and, best of all, I’d love to know which Italian word was translated as ‘hornswoggle’ as it might just come in useful one day.

I know that noir fiction isn’t supposed to be pleasant and when the cast of characters consists entirely of career criminals and corrupt politicians, a fair amount of violence and double-crossing is only to be expected. That much is delivered in generous quantity by Carlotto in At the End of A Dull Day, but I had hoped for a character – just one – I could cheer for, or fear for. However, it is the anti-hero Pellegrini’s attitude towards woman – and there do seem to be a lot of masochistic women in north-westItaly ready to be mistreated by him until their ‘mascara runs’ – which puts him beyond the pale.

A Noble Endeavour

I have thoroughly enjoyed the television series Endeavour which recounts the early adventures of a young Inspector Morse at the start of his police career in the Oxford of the early 1960s. Not only is the period detail spot-on, the casting and acting inspired and the plots convoluted enough for a skilled cruciverbalist, but in the last episode (of this series) we even got a glimpse of young Endeavour’s less-than-joyous domestic background.

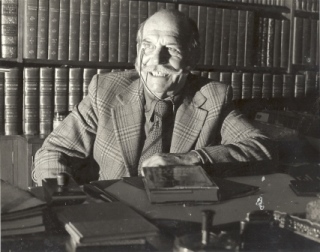

It was also a delight to spot my old contubernalis Colin Dexter making one of his famous cameo appearances early on in the episode, continuing a tradition started over twenty-five years ago, and it reminded me to send him a copy of the new edition of my historical thriller The Legend of Hereward for the very good reason that I have dedicated it to him.

I would never, of course, use this column for shameless self-promotion (though the book is now available through decent bookshops, Amazon and as a Kindle eBook) but my dedication is in part due to Colin having given the book a generous and favourable review in The Oldie when it first appeared, and partly because he pointed out to me that, like Hereward, he was born in Lincolnshire and therefore entitled to the local epithet of “Yellowbelly” – though no-one is quite sure where the name comes from.

Since reading The Legend of Hereward, Colin has often remarked on the fact that he is proud to be one of the three most famous “Yellowbellies” originating from Lincolnshire, alongside Nicholas Parsons and Hereward. Oddly enough, Colin forgets to mention Margaret Thatcher. Or perhaps he doesn’t.

1953 and All That

I have been rather tardy in recognising James Bond’s Diamond Jubilee, as the iconic secret agent made his debut in Casino Royale sixty years ago in April, but it has given me the idea of casting a quick look at what the competition was in 1953, a year which still had sugar rationing, but also a Coronation (which boosted the spread of television sets) and saw the conquest of Everest and two guys in a Cambridge pub discovering DNA. (Well, they probably went to the pub – The Eagle – afterwards.)

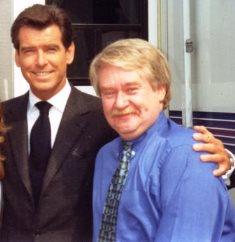

1953 was also marked by the birth of another ‘Bond’ – Pierce Brosnan, who generously invited me on to the set of The World Is Not Enough; a visit which inspired my 2001 thriller Lights, Camera, Angel! Of course Pierce’s arrival into this world was not in any way competition for fictional super-agent Bond. He and his creator Ian Fleming already had quite enough of that.

That ‘Prince of Thriller Writers’ Dennis Wheatley, who never used three words when twelve would do, had over 30 best-sellers under his belt by 1953, when he published Curtain of Fear which was set mostly in Prague and showed just how beastly the Bolsheviks really were in their ideological fortress behind the Iron Curtain. Geoffrey Household was just getting back into thriller writing a dozen years after the stunning impact of his Rogue Male and the reliable Hammond Innes continued to turn out a string of adventure novels with exotic settings and ordinary, sometimes slightly damaged, ‘Everyman’ heroes. Yet none of these three popular writers (and one could add Victor Canning and Nevil Shute) had really embraced the idea of a tough, professional secret agent like James Bond – or perhaps one should say ‘special’ agent as there seemed to be little ‘secret’ about Bond with his rather ostentatious tastes in wine, women and fast cars. It was the dangerous charisma of Bond, the suave thug who was on our side for once, which Fleming brought to the party and that trait of ruthless resourcefulness was to find its way into the adventure thrillers of Alistair Maclean and the spy fiction fantasies of a host of imitators in the 1960s.

Back in 1953, however, Fleming and Bond did have at least one direct competitor: a freelance special agent with what was, effectively, a ‘licence to kill’ from the British government whose creation pre-dated that of 007 by two years: Johnny Fedora.

The first Fedora thriller, Secret Ministry, was published in 1951 just as author Shaun Lloyd McCarthy (1928-2001) was graduating from Oxford University. Under the pen-name Desmond Cory, he would write fifteen Fedora titles in total, including Dead Man Falling in 1953 each one, as the reviewers said containing ‘colourful action, copious carnage and elaborate intrigue’. At the time, Fedora with his half-Irish, half-Spanish background, his eye for the damsel in distress and his wartime training which equipped him superbly for his battles with Nazis and ex-Nazis (and later the KGB), were understandably exactly the elements readers were looking for in their special agents and I’m happy to say that Johnny Fedora has not been forgotten. Thanks to the efforts of the sons of ‘Desmond Cory’ Dead Man Falling has been made available as an eBook and appears to be doing rather well, currently ranked #23 in Amazon’s best-selling downloads of spy stories and garnering dozens of positive reviews. A later Fedora novel, from the 1960s, Undertow, is also available as a Top Notch Thriller.

From the ‘Class of ’53 there are two other examples of spy-fi well worth mentioning, but which probably have been unjustly forgotten and relegated to remaining in the shadow of Bond. Not that, I think, the authors ever saw their fictional agents in the same way that Ian Fleming saw James Bond and both authors had other, personal, agendas for their stories rather than simply providing much needed escapist entertainment in Austerity Britain.

For his debut novel, A Flag in the City, Christopher Landon clearly drew on his own experiences as a serving British officer in the Middle East during World War II. His thriller is set in Persia (Iran) in 1943 and his hero, Major Bill Conway is in charge of running truck convoys of supplies and war material across the country to Britain’s Russian allies. Isolated in the south of the country with only a few troops, Conway becomes aware that the local population is being urged to rebel against the presence of the British (who ran the oil companies) by the mysterious ‘Friends of Iran’ organization. When he is personally threatened, he comes across as genuinely frightened but when the threats materialise into violence, he stiffens the sinews and becomes a real dog of war, is recruited into British counter-intelligence and sets out to hunt down the German agents behind the ‘Friends of Iran’ before they can put their master plan into action.

Conway is a believable and sympathetic hero, resourceful but also vulnerable, although I think this was his only appearance in print as Christopher Landon went on to write crime novels and, of course, the book (and film) for which he is best remembered, Ice Cold In Alex, before his untimely death in 1961. With its unusual locations, which include a gunfight in the ruins of Persepolis, credible characters and great pace, A Flag in the City is a remarkably good thriller which holds up well sixty years on.

Julian Symons never wrote anything uninteresting, but you get the feeling that his heart wasn’t really in his 1953 spy thriller The Broken Penny. His hero, Charles Garden (an embarrassing name to pick when the action, as it does twice, moves into a garden) is a former liberal socialist/anarchist who fought in the Spanish Civil War and in WW2 as an agent parachuted into a small European country (never named) shaped like a ‘broken penny’ and now under Communist rule. Recruited by a shady section of British Intelligence, Garden has to escort the political leader in exile back to the broken penny country to lead a popular uprising of liberal socialists against the hard-line Stalinists.

Hard-core spy-fi fans will find little ‘tradecraft’ or realistic detail in Symons’ deliberately unrealistic approach. There are characters called ‘Mr Hards’, ‘Latterley’, ‘Foskett’, ‘Floy’ and ‘Fanny Bone’ and bodies when they turn up – as they do – provoke absolutely no reaction from those who find them, which along with the two people who are ‘shot neatly in the head’, give the whole book more the feel of a ‘Golden Age’ detective story than a spy thriller. There are nods to Buchan, Greene and G.K. Chesterton in the plotting – and possibly Michael Innes in a farcical scene set during an army ‘Gas Artillery’ exercise in the Kent countryside; but in the end this is a novel about lost innocence which other spy stories have done much more convincingly and with far more tension and suspense.

|

|

Moscow Rules, OK?

It does not require a mole to reveal the fact that I like a good spy story, whenever it was written and especially if it was written by a real-life former spy and one can play the game of trying to spot which bits of ‘tradecraft’ have been changed to protect the innocent. (Dan Fesperman’s The Double Game [Corvus, 2012] played this game out superbly as a full length spy novel.)

So I was really looking forward to Red Sparrow (from Simon & Schuster this month) by Jason Matthews, a retired 34-year CIA veteran, about a modern CIA operative being ‘honey-trapped’ (or is he?) in Putin’s Moscow.

Sadly I found I just couldn’t get into this book and feel I must be missing something for it comes with a stunning publicity blurb from no less than John Le Carré who claimed it was “Gripping and so utterly convincing” and the film rights have already been sold in a traditional ‘seven-figure deal’. I was also rather mystified by the recipes (over 40 of them) reproduced at the end of each chapter and usually bearing the name of a character recently featured.

Now these recipes may be coded messages. I mean, who apart from me reads spy-fiction writers for their cooking tips? Or they could, of course, be red herrings as the one in Chapter 20, for a “Proper French Omelet (sic)” is clearly faulty. It simply says ‘beat eggs with salt and pepper’ where any decent recipe would tell you: ‘combine, don’t beat!’ and it also forgets (a deliberate double-bluff perhaps?) to mention the key fact that for every two eggs used, a half-eggshell of water should be added to the mixture. How do I know this to be the correct method for the perfect omelette? Because I know it works perfectly; or it has every time I have followed it since, in 1967, I read Len Deighton’s marvellous French cook book Où Est Le Garlic?

If it’s Florence, It must be Fate

I simply have to go to Florence. It is fate and I cannot fight it, for I have acquired a trio of books to read, all of which point me to its not inconsiderable charms.

Of course knowing my luck, I will visit at the same time as hundreds of thousands of Americans descend on the city clutching copies of Dan Brown’s latest mega-seller Inferno – just as when I once visited Paris, I was surrounded by Americans using The Da Vinci Code as a guide book, desperately looking for an Exit from The Louvre.

Should you be unaware of the book – remote a possibility as that may be – Inferno begins with a dramatic shoot-out in a Florence hospital and has hero Robert Langdon following a trail of clues based on and around Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Reviews in this country have been less than kind, as they usually are for Dan Brown; a fact which has not dented his sales one tiny bit. Even the normally mild-mannered Jake Kerridge (the Clark Kent of crime reviewers) of the Daily Telegraph damned with very faint praise: ‘As a stylist, Brown gets better and better: where once he was abysmal he is now just very poor’ and concluded that the author longed ‘to escape from the prison of his pleonasm.’

Now ‘pleonasm’ is not, I suspect, a word you will find in a Dan Brown novel (though, obviously, you will find many others) and in a post-modernist twist could be turned on the Daily Telegraph itself as, apart from Jake’s half-page review of Inferno, that once-great newspaper ran a full page spoof of the novel a week before it was published. Surely that was too much newsprint and too many words dedicated to putting readers off a book when astute reviewers such as Jake Kerridge get only miniscule allocations of column inches to recommend books which are really good.

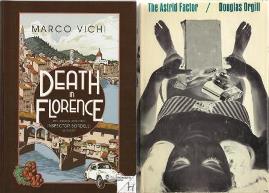

My other two Florence-set thrillers hark back to the famous floods of 1966, when the River Arno burst its banks and dramatically invaded the city. One was published in 1968 and the other comes out this summer.

Marco Vichi’s fourth Inspector Bordelli novel, Death in Florence, is published by Hodder in August and apart from cleaning up on all the crime-writing prizes going in Italy, the Bordelli series comes recommended as ‘Enjoyable, mystifying and well worth reading’ by my old chumette Jessica Mann, crime critic of the Literary Review, which is good enough for me.

Today journalist and military historian Douglas Orgill is probably best known for the ‘scientific’ or ‘eco’ thrillers he co-authored with scientist John Gribben, such as Brother Esau and The Sixth Winter. In the 1960s however, he wrote half-a-dozen very well regarded suspense thrillers, including The Astrid Factor, the climax of which takes place during the 1966 Florence flood.

I will be fascinated to see how the two books tackle the same setting and events. Douglas Orgill wrote his novel within a year of the floods actually happening. Marco Vichi would have been nine years old at the time, but was born and grew up in Florence.

No Orchids for Mr Wolfe

Last month I let slip that I had forgotten in which of Rex Stout’s excellent books Nero Wolfe’s orchid house gets machine-gunned by the bad guys. The first to remind me was spy-fiction expert Randall Masteller, of North Carolina. The book in question was The Second Confession, but there were no prizes.

Return of the Blues

This column has often championed unjustly forgotten or overlooked books but I cannot think of a book which has been sort of ‘mislaid’ for more than a decade as much as Tim Griggs’ Redemption Blues.

I really admired Tim Griggs’ 2009 thriller The Warning Bell, written under the pen-name Tom Macaulay and his more recent Victorian ripping yarn Distant Thunder (as T.D. Griggs), but what I hadn’t realised was just how big a success his earlier novel Redemption Blues had been, just about everywhere except here in the UK. I really admired Tim Griggs’ 2009 thriller The Warning Bell, written under the pen-name Tom Macaulay and his more recent Victorian ripping yarn Distant Thunder (as T.D. Griggs), but what I hadn’t realised was just how big a success his earlier novel Redemption Blues had been, just about everywhere except here in the UK.

First published in 2000 by Headline, Redemption Blues became a million-seller in Europe and, I think, Australia. Indeed German and French translations are still available although the British edition seemed to come and go almost without comment. I certainly do not remember being sent it for review, or indeed seeing any reviews of it anywhere and whilst it is not unusual for a British author to enjoy more success in Europe (despite the lobbying of UKIP) than at home, one usually gets to hear of it. However, I am delighted to say that Redemption Blues has now been reissued by Amazon and is also available as an eBook, and I wish it well getting its second wind.

Reach for the Stars

I have finally managed to see, in the comfort of my own stately home, the ‘controversial’ film Jack Reacher which is based on one of my favourite Lee Child thrillers, One Shot, and I have to say I found it jolly exciting and thoroughly enjoyable.

When I say ‘controversial’ I refer only to the hysteria whipped up by fans of the Jack Reacher character – sometimes known as ‘Reacher’s Creatures’– at the casting of Tom Cruise as their hero almost entirely on heightist grounds, moaning and wailing in any interweb chat room that would listen (and probably on Twitter, whatever that is) that Cruise was simply not big enough to fill Reacher’s fictional boots.

Being of non-heroic stature myself, I have little time for such carpings. I mean, which of us, like Alan Ladd, has not had to stand on a box to complete a love scene at some point? Having seen the film, I have even less sympathy, for Cruise does an excellent job even if the film seems to have a higher body count that the original novel and it was a delight to see Robert Duvall hamming it up in support, not to mention discovering Werner Herzog, no less, playing the bad guy.

Classic Corner

I have never been backward in coming forward to promote the Top Notch Thriller imprint which rescues Great British thrillers which do not deserve to be forgotten. Indeed, as Series Editor, I am morally and probably contractually obliged to do so and it is with great pride that I report the latest titles are Berkely Mather’s The Terminators, from 1971, and Antony Melville-Ross’ Tightrope from 1981.

Details of both books and all Top Notch Thrillers (there have been 30 titles re-issued in the past three years) can be found on www.ostarapublishing.co.uk along with information on the authors, whose life stories are almost as thrilling as their fiction.

Berkely Mather was the pen-name of John Evan Weston-Davies (1909-1996), whose family emigrated to Australia in 1913 where they were deserted by an alcoholic father in 1916. Returning to Britain just as the Great Depression hit, a penniless, unqualified Weston-Davies joined the army in 1932 and was posted to India where Gunner Davies successfully passed himself off as an officer for several years before being discovered. Transferring to the Indian Army as a sergeant, he began writing stories for Forces newspapers and magazines, graduating to writing radio plays and then television scripts (even though he had never seen a television!) after the war, whilst still in the army. As a civilian back in England in the 1950s he became one of the most prolific scriptwriters of the decade, receiving a special award for his work from the Crime Writers Association in 1961 and becoming CWA Chairman 1966-67. He was one of the scriptwriters on the first Bond film Dr No and his television work went on to include early episodes of The Avengers. His best known novels featured an Indian setting and his freelance agent hero Idwal Rees. The Pass Beyond Kashmir was the first and The Terminators was the second in the series.

Antony Melville-Ross (1920-1993) was never destined for an uninteresting life. His American explorer grandfather (a cousin of Herman Melville) was killed by a poisoned dart whilst on an archaeological expedition in a South American jungle. His father was first a balloonist during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904 and then a pilot for Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution before becoming a test pilot of new fighter planes in England during WW1, where he met his wife and their son Antony was born. ‘Just to show off’ as he later said, Antony joined the Royal Navy aged 18 and in 1941 transferred to the submarine service in which he served with distinction throughout WW2, being involved in the sinking of 25 enemy vessels. After the war he learned Polish and worked in Intelligence as a ‘Naval Attaché’ (and we all know what that means) in Warsaw before leaving the Navy in 1952 to work for BP on oil exploration projects in Libya and South America. He took up thriller writing at the age of 58 and his fast-moving spy thrillers starring Alaric Trelawney are thought to be based substantially on his own experiences.

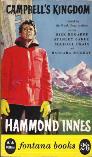

Yet no sooner have two classic thrillers been reissued, than four more come along, this time from Vintage Classics, highlighting the work of Hammond Innes (1913-1998), with the promise of a further ten titles and all in eBook format for the first time.

The Lonely Skier, from 1948, comes with an astute Introduction from Dame Stella Rimington and Andy McNab provides an equally enthusiastic and perceptive one for Campbell’s Kingdom, which first appeared in 1952. Both of these books were filmed and my much-loved 1960 Fontana paperback edition of the latter depicts Innes’ quintessentially lonely and vulnerable ‘Everyman’ hero as played in the film by Dirk Bogarde (supported by a roll-call of British character actors).

To accompany these two Innes titles this month, Vintage are also re-publishing The Wreck of the Mary Deare, his famous shipwreck adventure set off the Channel Islands (filmed with Gary Cooper, Charlton Heston and a young Richard Harris), and his remarkable wartime thriller Wreckers Must Breath about the discovery of a secret Nazi U-boat base in sea caves on the Cornwall coast, which I believe was written in 1939 in the very first months of the war.

Coming Up

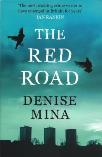

July looks like being another good month for ‘Tartan Noir’ – a useful, if lazy, catch-all term for crime novels which may or may not be noir and which rarely mention tartan, but whose authors and settings are invariably Scottish.

The award-winning Denise Mina like another famous Glaswegian (recently retired), has an impressive trophy cabinet and will probably add to it with The Red Road which is published by Orion on July 4th. On the very same day, Mantle will publish the second novel by Malcolm Mackay, a native of Stornoway, How A Gunman Says Goodbye, although the book is not set in the beautiful Western Isles but in the far wilder and less peaceful Glasgow underworld.

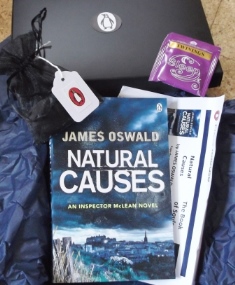

And just to make sure that July 4th will henceforth become known as Scotland’s Independence Day rather than America’s, Penguin publish the second Inspector McLean thriller, The Book of Souls, by East Fife farmer James Oswald, remarkably less than two months after publishing his first, Natural Causes.

Now both Oswald’s books were ‘bestselling’ eBooks last year, before actually making it into print and as with all eBooks, the cheaper they are, the more vitriolic the Kindle-using critic seems to be. For Natural Causes, one reader (or should that be ‘downloader’?) who got the book for nothing reviewed it as ‘Typical ITV drama stuff but unfortunately with no adverts to break it up’, which proves that you just can’t please some people.

To be fair, Penguin are putting a marvellous promotional effort behind the books and reviewers have been treated to not only a free book, but also a sachet of soothing herbal bath salts and a tea-bag of something called ‘sleep tea’ which will hopefully help the reviewer recover from the shocking revelations of the book. Unfortunately, for this particular reviewer, the promise of a solitary bubble bath and a non-alcoholic beverage are unlikely to cut the mustard. Like I said, there’s just no pleasing some people.

Now That’s What I Call Nordic Noir

Readers of this column will know of my endearing love and admiration for Scandinavian crime fiction in all its myriad and diverse forms, in fact Saturday nights will never be the same without an eight-hour chunk of Scandi-crime television. for Scandinavian crime fiction in all its myriad and diverse forms, in fact Saturday nights will never be the same without an eight-hour chunk of Scandi-crime television.

I am therefore straining at the bit in anticipation the latest Swedish crime drama 100 High, starring Michael Nyquist, a 12-part crime series which I am informed begins shooting this month. The author behind the series is that renowned Scandinavian philosopher Kenvik Bruensson, who bears an uncanny resemblance to my old mate Irishman Ken Bruen.

Surely not….???

Toodles!

The Ripster

|