|

Court Circular

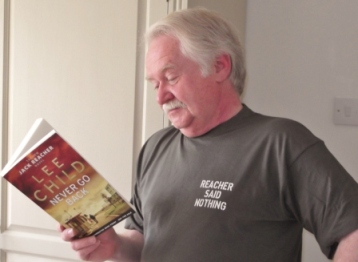

I was almost fashionably late for the social event of the year, the Crime In The Court street party brilliantly hosted as usual by David Headley and the staff of Goldsboro Books, the reason being that I had just received an advance copy of Never Go Back, the new Jack Reacher thriller by Lee Child, which Bantam will publish at the end of August.

Of course I could not resist donning the official ‘Reacher Said Nothing’ t-shirt, which all Reacher reviewers must wear by law now, and sneaking an early peek just in case I should manage to run into Lee whilst he visits the UK to receive the Crime Writers’ Diamond Dagger Award.

All my worries about tardiness evaporated the instant I arrived at Cecil Court in London’s muggy West End as I was greeted most warmly (so warmly the ambient temperature rose several degrees) by the vivacious Louise Penny, surely Canada’s sexiest lumberjack.

As we had not seen each other for several years, there was much catching up to be done and I particularly wanted to pursue a French linguistic phenomenon mentioned, tangentially, in Louise’s latest book The Beautiful Mystery which has just appeared in paperback from Sphere. Our intellectual musings would take too long to report here, but Louise and I will do so at some point in the future when we feel the world is ready for La complainte du phoque et morse.

And then it was off to do the rounds of this marvellous street party, noting that David Headley had once again made a pact with Satan to ensure fine, thirst-inducing weather for the event as I had several errands to run among the assembled great and good of the crime writing world.

Most pleasurably I had to seek out the frighteningly talented South African Mari De Villiers, author of the outstanding first novel City of Blood, and pass on (from the wilds of East Anglia) all best wishes from our mutual friend Lesley Grant-Adamson.

Apart from making new friends, events such as Crime in the Court are vital in order to renew old acquaintances which ought never to be forgot and in my case, being more of a country vole rather than a town mouse these days, it was the perfect excuse to discuss upcoming thrillers with boyishly enthusiastic publishers such as Bill Scott-Kerr and Edwin Buckhalter, clink glasses with fellow authors Roger Morris and Adrian Magson and fellow bloggers, the svelte Chris Simmons and the voluptuous Ayo Onatade.

Unfortunately, one person I had been really looking forward to seeing, the gorgeous Anne Zouroudi, whose latest The Feast of Artemis is the perfect book to take on a Greek holiday without the discomfort of travelling there, was unable to attend.

Always thoughtful of the needs of others, particularly elderly gentlemen easily confused by the hustle and bustle of the capital, Anne had however despatched two of her most intelligent and attractive publicists in order to look after me.

From our legal department

In 2003, some of my novels were dropped (far too casually I felt) from the lists of a British publisher and after due process, the rights to them reverted to me in 2005. Most have been recently reissued by another publisher including, for the first time, as eBooks…except that’s not quite correct as the original publisher, I discovered, had produced an eBook version of one title, despite no longer having the rights (indeed never having had electronic rights).

An embarrassed apology and a small royalty cheque eventually arrived after I voiced my amazement at such action and I was promised that the unauthorised eBook would be ‘taken down’. Now a literary agent has discovered that a second title of mine has been over-enthusiastically eBooked by the same publisher; again without permission. More apologies and token royalties followed, but it makes one worry about how many other authors this could be happening to.

Such incidents always give rise to the ‘cock-up or conspiracy?’ debate; though when talking about publishing, I usually come down firmly on the side of the former.

Sharpe End

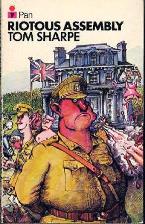

I was saddened to hear of the death of my old teacher, Tom Sharpe at the age of 85, although I had not seen him for many years. In the very early 1970s, Tom taught a course in Russian history, specifically (and in great detail) the history of the 1917 Revolution at Cambridgeshire College of Arts & Technology which later became the setting for his novels featuring the accident prone hero ‘Wilt’.

Tom was not a tutor one picked a fight with. Feared for his acidic tongue and withering sarcasm, he did not suffer fools gladly or otherwise and knew his subject backwards, interspersing the flow of narrative history with highly entertaining anecdotes about Karl Marx’s legendary pub crawls in Soho (true), Lenin’s ruthlessness towards those who supported him let alone his enemies, and the horrors witnessed by Swallows and Amazons author Arthur Ransome, a British spy in Russia in 1919 (whom Tom claimed he knew and we believed him).

It was only because we frequented the same pub, The Tiger, in Cambridge that I learned of my tutor’s other career as a writer. As students we had all heard of Tom’s experiences as a teacher, then photographer, then suspected Communist agitator in South Africa in the 1950s, and that he had made no secret of his loathing of the regime there; so much so that the South African secret police BOSS had made sure he was deported. The gossip in The Tiger was that Tom had written several dozen spectacularly unsuccessful plays and was depressed at the thought of being a failed dramatist. It was fellow lecturer (and noted poet) John James who, according to saloon bar legend, suggested that instead of trying to write overtly political plays, Tom should write a novel based on his experiences in South Africa and incorporate all the rude stories and gross anecdotes with which he regaled the regulars in the pub. Tom supposedly protested that “Nobody would ever publish it!” but went away and wrote Riotous Assembly. The rest was history, something which Tom soon gave up teaching to become the most successful English comic novelist since Wodehouse or Waugh.

When the book came out I was working on the Student Union newspaper (circulation: 250) and cheekily rang the publisher for a review copy. I gave it a great review, partly because it was a darkly hilarious swipe at apartheid and partly because Tom was still marking my essays, and Tom seemed genuinely pleased and a little embarrassed by all the praise he was starting to receive. He signed my first edition – subsequently ‘borrowed’ by a ‘friend’ and never seen again – and I passed history.

East, West, Spying’s Best

The cover of The Shanghai Factor, out this month from Head of Zeus, carries a quote from Lee Child claiming that ‘Charles McCarry is better than John Le Carré. Which makes him perhaps the best ever.’ Whilst I feel that the always generous Lee may have over-egged the pudding a tad, there is no doubt that Charles McCarry (himself a former CIA operative) is a master of his craft and should be regarded as an American national treasure.

The Shanghai Factor is a classic spy story, which is to say it is all about deception and betrayal. The main protagonist is an un-named American, well-educated, from a well-heeled background, student of Chinese languages who is embedded into Shanghai (capitalist China’s window on the west) as a sleeper agent with a long-term mission to gather intelligence on the hierarchy of the dreaded Guoanbu, China’s own intelligence service. When that mission seems to fail, the sleeper returns to America where he offers himself as double-agent to the Guoanbu before twisting the plot to recruit the Guoanbu agent trying to recruit him! All his efforts could be in vain, however, when it becomes clear that whilst the CIA are trying to infiltrate the Guoanbu, the Guoanbu has already infiltrated the CIA and the escalating threats against the sleeper agent come not so much from the perils of espionage but more from even older Chinese traditions of vengeance.

This is a fascinating read, with insights into the world of young, rich Chinese ‘princelings’ who are at heart ‘secret Americans’ rather than die-hard communist party members and a restrained, non-judgemental character study of an intelligent, patriotic, but painfully lonely young man caught up in the spider’s web of spying.

Shurely shome mishtake…

On 1st June, that once great newspaper The Daily Telegraph published a supplement entitled 500 Must Read Books (Part 1), recommending a dozen or so titles in various subject categories in a little detail and then adding another half dozen titles in a “Best of the Rest” postscript to each section.

As with all lists, the fun is in arguing about what was not included or with some of the judgements of the anonymous compilers – was Where Eagles Dare really ‘the greatest war film of all time’? – but in this instance, my argument is not with the Thrillers category, but with the Food And Drink section. After noting works by culinary experts such as Elizabeth David, Nigel Slater and the saintly Nigella Lawson, there is a “Best of the Rest” addendum which, for reasons I cannot quite comprehend, includes A Long Finish by Michael Dibdin and Hangover Square by Patrick Hamilton. Surely there must have been some mistake by an over-enthusiastic (i.e. young) sub-editor, should such things still exist, or was somebody at the Telegraph simply having a larf?

When the Mandrake Screams

When I heard I was being sent a novel with ‘Mandrake’ in the title, I immediately thought of my old chum Barry Norman’s debut thriller The Matter of Mandrake from 1967.

However, The Mandrake File turns out to be a brand new thriller, at least to the UK, from a brand new publisher and a French writer, Cédric Bannel, new to me.

The plot revolves the hunt for the missing ‘Mandrake File’ in both Afghanistan and Switzerland, with the narrative jumping between the two. The scenes in war-ravaged Afghanistan (with a police detective called Osama) are far superior to the parallel action in Switzerland, where the protagonist is a rather vanilla character, Nick Snee, who works as an analyst for a very shady international security firm. Where Afghan policeman Osama Kandar tries to do police work under impossible conditions, Nick Snee stumbles along being naïve, innocent and incredibly lucky, following a trail of unbelievably convenient clues and coincidences.

At times fascinating and at times intensely irritating The Mandrake File, originally published in France in 2011, is the first thriller to appear here from Australian publisher Scribe, and though it strives to emulate John Le Carré, some of it comes across as second-hand Dan Brown. All the female characters in the book are invariably ‘gorgeous’ or the mutilated victims of either drug addiction or the Taliban and in the Swiss sections, the young hero Nick Snee appears naively sexist and patronising (not to say wrong) when he muses that: ‘Prostitutes have an uncanny ability to recognise cops and, more generally, anyone who might wish to harm them.’

Part of the problem may lie in the translation. One character is described literally and without irony as having ‘steam coming out of his ears’ another wears ‘protective sunglasses’. A pistol has a ‘security catch’ instead of a safety catch and the hero picks up a gun and ‘checks the cartridge’ instead of the magazine. Thereare explosives which ‘might have been endowed with a device allowing it to be detonated remotely’. Endowed??? And there are bits of pure carelessness such as: ‘the ceiling was so low that Osama’s head almost touched the ceiling’.

A few years ago I attended a session chaired by the erudite and cosmopolitan Peter Guttridge at a literary festival. The topic under discussion was ‘Crime in Translation’ with Peter presiding over a panel of French and Spanish writers and their translators. At question time, I asked the translators (only) if they could name a crime writer who wrote in English. Despite the fact that their panel was being chaired by an English crime writer, only one could and that was Raymond Chandler. A less diplomatic member of the audience asked if they could name a living crime writer and whilst all the translated authors could name several (despite one of them not realising that Agatha Christie was no longer with us), the translators rather shamefacedly admitted that they didn’t read crime fiction.I think it often shows; which is a pity. Sometimes the translation needs to be translated by someone who does.

A Cunning Canning

Victor Canning was a prolific and popular British thriller writer whose career spanned over fifty years and more than sixty novels, yet his name and his books slipped rapidly into obscurity disgracefully soon after his death in 1986. Until recently, that is, when a handful of titles have been reissued by Top Notch Thrillers, Arcturus Crime Classics, as Lulu titles and as Bello eBooks.

Coincidentally, the electronic Bello version of A Forest of Eyes became available this year at almost exactly the same time as I picked up the first paperback edition of Canning’s 1950 spy thriller set in Tito’s Yugoslavia. (For younger readers: this Yugoslavia no longer exists having been replaced by five or six countries in the Eurovision Song Contest.)

When the novel appeared, it was quickly popularised as an All In Pictures edition, which in my day would have been called a ‘comic book’ but these days it would be a ‘graphic novel’, and as a spy story it holds up remarkably well more than sixty years on. The basic plot involves an English engineer on business in the socialist (but not Stalinist) Yugoslavia who meets up with an English spy on a mission to help a defector get to Italy. When the professional spy is killed, the engineer takes over the mission, always conscious of the ‘forest of eyes’ watching his every move.

The novel is, stylistically, clearly influenced by the pre-war tales of Eric Ambler, which is no bad thing at all, and I think it one of Canning’s best books. The plot is believable, the action and suspense described in full measure and there are some fascinating character studies, not least the local Chief of Police, Zarko, who takes a professional (but humanitarian) interest in the hero while the secret policeman Lepovitch, sent from Belgrade, keeps a less charitable eye on him. In fact all the minor characters are well-drawn and when the reluctant English hero risks all to ‘go back for the girl’ (of course there’s a girl), there’s a faint premonition of the ending of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold which was to appear some thirteen years later.

I’m glad I found this cunning Canningand delighted to report that Canning expert John Higgins has found and rescued another Canning gem, Fountain Inn, which was the author’s first stab at a thriller (after several well-received ‘straight’ novels) and dates from 1939.

John Higgins runs a fascinating website dedicated to Victor Canning and his works (http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/wordscape/canning/index.html)

and has reissued several early Canning novels, including Fountain Inn through www.Lulu.com .

Going Medieval

Those mischievous Medieval Murderers are back with another collaborative compilation published by Simon & Schuster, The First Murder, which begins with a play first performed in a snowbound Welsh town in 1199.

Naturally, this being a book produced by the joint talents of Bernard Knight, Susanna Gregory, Karen Maitland, Philip Gooden and Ian Morson, inexplicable deaths accompany the performance and as the play is performed over the following centuries, it seems to attract more bad luck to all involved making the superstitions surrounding Shakespeare’s infamous “Scottish Play” seem positively childish.

One of the long standing members of the Medieval Murderers group is Ian Morson, author of the Oxford-based ‘Falconer’ series of historical mysteries and later this month the last in the Falconer series, which began in 1994, Falconer and the Rain of Blood will be published by Ostara as the first of their new imprint Ostara Originals which will concentrate (the clue is in the title) on new, previously unpublished crime fiction.

Is Hadrian’s Wall big enough?

Having suggested last month that July 4th may be a date more associated with the celebration of Scottish crime writing rather than with Americans celebrating Independence Day (it was a good film, but I don’t see why it should be celebrated so lavishly), because of new titles by Denise Mina, Malcolm Mackay and James Oswald all published on that auspicious day, I have to say hold the phone as I have been informed of another.

Scottish journalist Craig Robertson’s new thriller Witness The Dead was also a July 4th publication, from Simon & Schuster, and although Craig now resides in Stirling, the ancient capital of Scotland and the venue for this year’s Bloody Scotland convention 13-15 September, his tale is set in the badlands of Glasgow, which seems to be drawing Scottish crime writers like a moth to a flame, presumably all the crime in Edinburgh having been solved…

|

|

Praise Indeed

I am never slow to praise publishers where praise is deserved, though on occasion it is enough that you let them live, but perhaps I do not thank them as much, or as often, as I should. Certainly I thank whoever it was at Doubleday who thought to send me a copy of The Road Between Us by Nigel Farndale, which had not blipped on my radar at all and is not what you might call a conventional crime novel or thriller. It is, however, extremely good.

There are crimes, thrills and several mysteries as the plot of The Road Between Us covers homosexuality (when illegal), long-kept family secrets and a hint of incest, a suicide, a British diplomat held captive by the Taliban for 11 years in Afghanistan, Nazi concentration camps and the liberation of France in 1944; the action spanning 1939 to more or less the present day.

Not everything is resolved neatly – just like life – and there are some characters you want to know more about but the quality of the writing is so outstanding, these should not be counted as flaws. This is, I suppose, what is known as a ‘literary thriller’ about the loss of love and how a father and son, seventy years apart, deal with enforced separation from the loves of their lives. Art plays a key role in the book, sometimes a crucial one when it comes to surviving the most appalling horrors. (There are also cameo roles for Francis Bacon and David Hockney.)

The Road Between Us is a proper, grown-up novel with strong elements of the best suspense thrillers. At times it is positively uncomfortable, but like all the best thrillers, you have to keep turning the pages.

Winning the ‘Harry’

I was shamefully unaware of the creation of the H.R.F. Keating Award in time to include the news in last month’s column. Since then, the inaugural Award, which recognises outstanding achievement in crime-fiction related biography or criticism and which will surely become known as ‘The Harry’, has actually been made at the Crimefest convention in Bristol.

I am delighted to be able to report that the first Harry has gone to a Barry – my distinguished colleague Professor Barry Forshaw in recognition of his outstanding editorship of British Crime Writing: An Encyclopedia (sic), a magisterial two volume work published by Greenwood. It is an invaluable reference work which has pride of place on the strongest of the Ripster Hall bookshelves and I am particularly enamoured of Volume 2, pages 651-653.

The Roaring Twenties

The 1920s is a decade inevitably linked, usually in the same breath, with the Jazz Age, the Golden Age of English detective stories, the rise of both fascism and hem lines, talking pictures and Eliot Ness and the Untouchables. With all that going on, it’s no wonder that crime writers still look back fondly on the period when seeking inspiration, though the imaginative ones do not confine themselves to bodies in libraries or in Chicago garages on St Valentine’s Day.

Dan Smith has joined a growing sub-set of thriller writers who have opted for Russia at its most turbulent as their setting, such as William Ryan and Sam Eastland (aka Paul Watkins). Dan’s latest, Red Winter, out from Orion this month is specifically set in Central Russia in 1920, as civil war rages and Red and White armies compete to outscore each other when it comes to atrocities on the civilians who get in their way.

I am looking forward to reading this thriller, which seems to make good use of scary Russian folk tales, but I will do so only when the weather improves and I can get out the sun-lounger and the wine cooler. I think it something of a disservice on the part of Orion’s publicity department to claim that the book “will attract readers already hooked on the snowy landscapes of Scandi-crime” and I intend to prove them wrong.

Slipping along the decade to 1929, Damien Seaman chooses the dog days of Germany’s Weimar Republic for his thriller The Killing of Emma Gross from that innovative East Midlands publisher Five Leaves.

A police thriller which uses the infamous case of serial killer Peter Kürten – sometimes known as the ‘vampire of Düsseldorf’- the book comes with a publicity blurb from author Tony Black who feels it “will be rightly compared” to Gorky Park, Child 44 and Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels. The latter is the most likely comparison, given the German (rather than Russian) setting and it got me thinking as to how far behind I had fallen in my reading of the Gunther series, of which I have been a fan since the first, March Violets, appeared in 1989.

For legal reasons I no longer get to hear about Philip’s new books and I was horrified to find there were at least three titles – including A Man Without Breath published this very Spring – I had missed. Almost immediately I despatched one of the under-footmen to the nearest town with a bookshop and he returned with a paperback edition of Prague Fatale from 2011.

I am enjoying it immensely, having been hooked from the wonderfully disrespectful opening paragraph and whilst wishing Damien Seaman and Five Leaves all success, I have been reminded how high Philip Kerr has set the bar.

But I digress, and really should mention a recent reissue which was actually written in the 1920s – or almost.

The Doctor of Pimlico was first published in 1919 and is now revived by Oleander Press as part of their ‘London Bound’ series – crime novels set in London from the ‘Golden Age’ of detective fiction – and was one of the 150 books written by the prolific William Le Queux (1865-1927).

Intriguingly, The Doctor of Pimlico features as detective Walter Featherston who is, conveniently, a writer of detective stories, a trait which was to feature in the work of better-known crime writers of the so-called ‘Golden Age’. I say better known not because William Le Queux is an unknown writer (and an atrocious one according to Julian Symons), but because he is better known as one of the earliest writers of spy fiction.

Most famously, Le Queux was the author of The Great War in England in 1897, which he wrote in 1894 and had the Russians joining the French in an invasion of England. Le Queux was to follow this sensational ‘what if’ thriller with another, The Invasion of 1910, published in 1905 where he switched potential enemies and had the Germans as the invaders – a concept Erskine Childers handled far better in his 1903 classic The Riddle of the Sands.

Should your taste be for a slightly less “roaring” twenties (though no less tumultuous and violent), you might like to try the 1520s asa time frame and Renaissance Umbria in Italy as a setting. Here the skullduggery involves the painting of religious frescoes in churches by a team of itinerant artists who over-winter in a mountain village and find that their latest commission involves rather unconventional iconography.

Your Money or Your Life is a charming novella (or long short story) by the Anglo-Italian married duo Michael Jacob and Daniela De Gregorio who write as ‘Michael Gregorio’ and who live in Spoleto in Umbria, where the action begins. It is published, in English, by Les Éditions Didier of Paris in their attractive new imprint for short fiction: Paper Planes.

And into the Thirties…

Ian Sansom is best known in crime circles for his ‘Mobile Library’ mysteries set (initially) in Northern Ireland. Now he extends the technique of having his amateur detectives solving murder mysteries whilst touring the countryside in a news series known as ‘The County Guides Mysteries’.

First in the series is The Norfolk Mystery published by 4th Estate this month, which introduces our hero Stephen Sefton – an unemployed, footloose Cambridge graduate and veteran of the Spanish Civil War – who takes employment as a general factotum with the eccentric and hyper-active Professor Swanton Morley, a prolific author of non-fiction guides and encyclopaedias who believes fervently in education and self-help for the masses, earning him the delightfully Blair-ite title of ‘The People’s Professor’.

For his latest project, the professor aims to create a Domesday Book for the 1930s through a series of County Guides detailing local tradition and habit. Naturally, this gives him, his rebellious daughter and his new assistant the chance to tour England, solving mysteries as they go. Their extended road trip, in the comfort of a stylish Lagonda, begins in darkest Norfolk (fittingly enough, as Swanton Morley is a village there) where, of course, murder lurks – as it will do in other English counties in the 39 books due to follow!

If my arithmetic and geography are correct, Ian Sansom’s total of 40 English counties for 1937/8 includes the Isle of Wight and correctly recognises that Yorkshire, like Gaul, was divided into three parts. Mr Sansom has set himself a fascinating if daunting task and whilst not wishing to discourage him in any way (especially not on the strength of the wry humour and careful observation shown in the first instalment), I would simply mention that Sue Grafton embarked on her ‘Alphabet mysteries’ starring private eye Kinsey Millhone in 1982 with A is for Alibi and the latest, W is for Wasted appears later this year with, presumably, only three more to go. At that rate – 23 books in 31 years – Mr Sansom should be ending his series, possibly in one of the lesser counties such as Lancashire, around the year 2064 give or take a few months.

It will be an interesting journey not just for his characters, a delightful trio of oddball Musketeers, but for his readers.

An honour not a duty

It was an honour and a pleasure to act as one half of the bodyguard team (along with David Headley, London’s most fashionable bookseller) for that maestro of the history mystery Paul Doherty at the official launch of his one hundredth novel.

It was not the easiest of tasks as on occasion David and I had to forcibly restrain Dr Doherty from giving away the ending of his new novel from Headline, The Last of Days.

In a formidable, note-free lecture Paul Doherty had explained to an enthralled audience the internal politics of the Tudor court of Henry VIII which had drawn him to his subject matter. The way he told it, it could easily have been Mario Puzo’s inspiration for The Godfather and whoever said ‘history is more or less bunk’ was talking out of the exhaust pipe of a Model T.

Trains now standing

I was a great fan of David Downing’s first four wartime thrillers featuring his spy hero John Russell and all named after Berlin stations, but for legal reasons I never got to see the fifth, Lehrter Station, which moved the series into the post-war period. Now comes the sixth, and last, Masaryk Station, set in 1948 as the Cold War starts to exert its icy grip.

Almost before we have time to digest this latest, Old Street Publishing launches Downing’s new series in September with Jack of Spies.

For his new venture, Downing changes wars, with Jack of Spies opening in the run-up to World War I in the German ‘protectorate’ in China, which was and still is famed for the Tsingtao lager brewery, the Germans having invented one of the few things the Chinese had not got around to.

It is not surprising given that next year is the centenary of the outbreak of WW1 that writers should be drawn to the subject. Rob Ryan and Andrew Williams have done so recently and this month they are joined by Robert Goddard with his new novel The Ways of the World, from Bantam, which is the first book in a planned trilogy opening at the Paris peace conference of 1919.

Atkins Diet?

Several years ago Maxim Jakubowski of Murder One fame recommended (i.e. made me buy) a copy of Ace Atkins’ first novel Crossroad Blues, which I seem to recall enjoying very much and more recently I reported the fact that Atkins had been commissioned to continue the ‘Spenser’ private eye series following the death of Robert B. Parker.

For reasons probably legal I have not seen any of Ace’s ‘Spenser’ books, if indeed they have been published here, which was something I had rather looked forward to, being a fan of Bob Parker’s work. It was quite a surprise then, when a new Ace Atkins novel finally did arrive at Ripster Hall, to find that it was not a ‘Spenser’ but the second in his own Edgar-nominated series to feature former US Army Ranger Quinn Colson.

The Lost Ones, to be published by Corsair in September is set in Mississippi, where Atkins now lives (not far from John Grisham I believe) and has hero Colson recently elected as the Sheriff of Tibbehah County. It sounds a far cry from Spenser’s usual hunting ground in metropolitan Boston, but I would have liked to have seen how Atkins tackled that.

Lavorare in Toscana

For the first time in many years I have been allowed a leave of absence by the tyrannical editor of this outstanding organ and will therefore be handing over the onerous task of filling theAugust Getting Away With Murder column to the very talented Mr Jake Kerridge of the Daily Telegraph.

I have not a scintilla of doubt that my regular readers will be well-served by the knowledgeable and generous (not to mention irritatingly young) Mr K and my mind will be left free to concentrate on the inaugural Chianti Crime Festival in Tuscany, which I have been asked to chair despite my protests that I am no longer of an age to traverse the Alps no matter how well-behaved the elephants are.

Ciao lettori!

The Ripster.

|