|

Welcoming the New Year in Style

I can think of no better way to kick start 2014 than by sharing a glass or two of bubbly with my old chum Deryn Lake, the Queen of the Georgian history-mystery, especially when the venue is The Old Bell Tavern, a 17th century tavern on London’s historic Fleet Street.

It was a fitting venue as The Old Bell (famous for providing lodging to the stonemasons employed by Sir Christopher Wren whilst he was renovating a local church…) is actually mentioned in Deryn’s new novel Death on the Rocks now out from those supremely civilised publishers Severn House. It is – much to the relief of the host of ardent fans who filled the tavern to bursting point – a new adventure for Deryn’s most popular hero, John Rawlings, Apothecary, of Piccadilly and sees him dragged away from the snug bars of London to investigate murderous goings-on in Bristol, now the home of the annual Crimefest convention, but at the time of Death on the Rocks at the epicentre of the British slave trade.

Poirot and Me

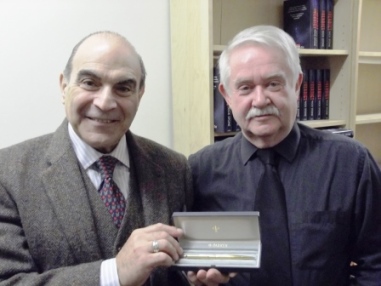

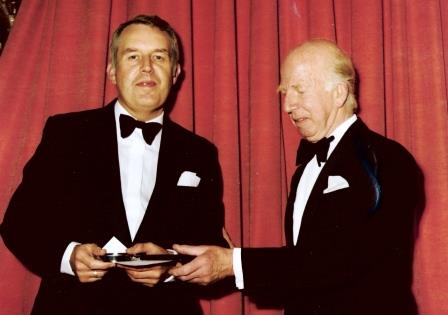

Twenty-two years ago, in December 1991, my novel Angels In Arms won me my second Last Laugh Award from the Crime Writers’ Association, which was presented at a lavish feast in central London by David Suchet, then embarking on his definitive interpretation of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot, a career celebrated in the Christmas bestseller Poirot and Me.

As that same event saw the presentation of a Gold Dagger to Barbara Vine (who as Ruth Rendell also won the Diamond Dagger that year), a Silver Dagger to Frances Fyfield and the John Creasey Award for best newcomer to Walter Mosley, by the time it got to the comedy award, I think the photographers on duty (if there were any) had hit the cash bar. Thus, in those far-off days before mobile phone cameras, the event went unrecorded, much to my longstanding regret.

However, having told my sob story to those nice people at Headline, publishers of David Suchet’s memoir, they suggested that I would be welcome to try and persuade Mr Suchet into a recreation of that presentation at a signing session to be held at the outrageously fashionable Goldsboro Books in Cecil Court. And so with thanks to Headline, to Goldsboro Books and, of course, to David Suchet, who was keen to oblige, the presentation of the 1991 Last Laugh Award was re-enacted for the cameras twenty-two years (almost to the day) later.

Private Eyes (Time-lagged)

Over Christmas I treated myself to reading two private-eye novels which follow many of the accepted traditions of the private-eye sub-genre but are set in different countries and adopt different moral compasses to guide their plots. Interestingly, though I do not understand why, both are set ten or more years ago. One is by that master craftsman of the American spy thriller, Robert Littell, the other by a leading light (perhaps the leading light) of the ‘Mediterranean Noir’ movement, Italian Massimo Carlotto.

Robert Littell’s A Nasty Piece of Work [Duckworth Overlook] is by far the better of the two as one would expect for although something of a departure from his usual spy fiction, Littell is master craftsman when it comes to clever thrillers. With a backdrop of New Mexico (a location he used brilliantly in 1996 in Walking Back the Cat) the new novel features Lemuel Gunn, an ex-homicide detective (and former CIA agent who served, with reservations, in Afghanistan) turned private eye, operating out of a mobile home – which may be a homage to Jim Rockford and his files. Time-wise, the setting may also reflect the days and methods of Jim Rockford, for this is the era where a ‘portable phone’ is a distinct novelty and newspaper photographers still use cameras with film in them.

Quite why the book is set in the 20th rather than 21st century (although Lemuel Gunn is a hero who could have come proudly from the 19th) isn’t clear, at least to me as it neither adds to nor detracts from the plot, which is classic private eye stuff. In fact A Nasty Piece of Work could be held up as a template for the private eye story, with its resourceful and very human hero battling rival mobster families whilst the three women in his life look on disapprovingly

Massimo Carlotto’s The Master of Knots [Europa World Noir] is also set in the near past and is more problematic. In the early sections of the book, there are constant references to the Italian currency being lira not Euros and sado-masochist pornography being distributed on video-tapes, rather than on DVDs or via the Internet. About a hundred pages in, it becomes clear that the year must be 2001, as the G8 economic summit is taking place in Genoa, a fact which is really only tangential to the plot of the book and clearly the anti-G8 riots and the brutal over-reaction of the police in quashing the protests have more resonance with the Italian Left than with a wider audience.

The book features Carlotto’s anti-hero Marco ‘The Alligator’ Buratti, an ex-con, former-terrorist, night club owner and blues singer tracking down a missing woman with a penchant for slavery, bondage and general unpleasantness. In turn this leads to a vendetta against The Master of Knots of the title who is behind an organised BDSM ring and expanding his operation into snuff movies.

The problem I have with recent ‘Alligator’ books is that the hero is not very heroic or hardboiled for a hardboiled anti-hero and apart from drinking vast amounts of Calvados, he actually does very little. Conveniently, he always has others to do the dangerous stuff and in the end, in the ultimate tough-guy cop-out, he gets the police in to deal with the diabolic villain. I know that in true noir tradition, it is not necessary to have a hero to cheer for, but usually there has to be a character for the reader to care about.

In the past I have taken the translators of Carlotto’s work to task and am happy to say that The Master of Knots has only a couple of jarring moments. As every thriller-reader knows, you might get sprayed with bullets from a Kalashnikov, but not sprayed ‘with Kalashnikov bullets’, and an Italian (or any European) is unlikely to describe a pistol as ‘a short-barrelled thirty-eight-millimeter (sic) handgun.’

The Only Way (really) Is Essex

Essex has been a much-maligned county, probably since the day rude and crude Roman soldiery coined the expression Res rarissima virgo inter Trinovantes, and strangers – notably the metropolitan elite who live within the M25 – are blissful in their ignorance of the attractions of the Essex countryside and the fact that it hosts one of the largest and most ambitions annual book festivals in the country.

This year’s Essex Book Fest runs through March and utilises venues across the county including libraries, theatres, universities, art galleries, churches, a Martello tower and tea rooms, from Canvey Island to Dedham Vale. Full details of a wealth of events can be found on www.essexbookfestival.org.uk for I have here only the space to concentrate on those events which relate to crime fiction, in what must be the strongest promotion of crime writing since the Festival began.

The first crime-themed event this year is also one of the longest running. The annual Dorothy L. Sayers Lecture must now be in its 24th if not 25th year and is given by a celebrated (or in my case, notorious) crime-writer in the Library at Witham, home of the Dorothy L. Sayers Centre and next door to the house where she lived for many years. This year’s lecturer (on March 6th) is my eminent chumette Natasha Cooper, a long-standing admirer of ‘DLS’.

The Festival’s second criminous event also centres on the career of a famous Essex Girl, Margery Allingham, and her distinguished ‘Golden Age’ hero Albert Campion. The talk ‘Albert Campion and Me’ is a personal memoir from a far less distinguished crime writer – myself – and takesplace at the Great Baddow Library near Chelmsford on March 10th.

Talking about Essex Girls: Cooper and Ripster

Then in rapid succession, a newcomer and an old hand in the crime fiction business. The newcomer is David Thorne who will be talking about his debut thriller East of Innocence (just out from Corvus) which comes with the catch-line ‘On the edge of London and way outside the law…Welcome to Essex’.

Despite such an ominous advertisement, I am sure David Thorne will get a warm welcome when he appears at Shenfield Library on March 11th. I know that veteran author (of over 90 books I’m told) and raconteur Simon Brett will when he appears at Halstead Library on March 12th.

March 17th sees the first of two female ‘double-headers’ of the Festival when Barbara Nadel and Anya Lipska appear in conversation at Canvey Library on Canvey Island. Both authors will be talking about their craft but I suspect will concentrate on the background settings to their novels, Barbara Nadel being best known for her Istanbul-set mysteries and relative newcomer Anya Lipska has already established a reputation for insightful plots set in and among London’s East End Polish community. A day later (March 18th) and some thirty miles to the north, Michael Dobbs, of House of Cards fame, will be appearing at Maldon Library to talk about his new thriller The King Is Dead.

Braintree Library on March 25th sees, I think, the first appearance of Louise Welsh at the Festival, launching her new novel A Lovely Way To Burn (from John Murray) which is actually the first novel in a planned Plague Times trilogy.

An ambitious project, the Plague Times trilogy is set during a global pandemic where London is a city full of death…so who is going to notice the odd murder? I have no doubt that much will be heard of A Lovely Way To Burn in the coming months and I am already taking bets on how many reviewers will use the word “infectious”.

The final (crime fiction) event of the Festival is the second female two-hander on ‘How to Plot the Perfect Murder’, although I am assuming that means how to plot and write rather than commit, and features those ‘expert crime writers’ Claire McGowan and Julia Crouch speaking at the University Centre, Harlow on March 29th.

There are many other goodies in the Festival to appeal to anyone with interests other than crime writing, from appearances by Peter Snow, Rageh Omaar, Joanna Trollope, Ann Widdecombe, Terry Waite, Henry Blofeld and the splendid performance poet Martin Newell. In March at least it really does look like the only way for the literate is Essex.

East of Peterborough

I was rather surprised not see Essex-based debut novelist Eva Dolan included in this year’s Book Festival, as Long Way Home (just out from Harvill Secker) is a noble attempt to put crime fiction in the context – the often grim context – of ‘multicultural’ modern Britain.

The perceived ‘problem’ of immigration into Britain certainly goes back to the 5th Century when a pompous Romano-Briton observed Saxons and Jutes arriving in Kent and muttered “Those bloody English coming over here, taking our farms…” and among the illustrated manuscripts now lost from those ‘Dark Ages’ were probably several prototypes for the Daily Mail. Other crime writers have tackled similar issues – John Harvey’s Inspector Resnick had a proud Polish heritage and, in 2005, Janet Neel’s Ticket To Ride covered the exploitation of migrant agricultural workers in the Fenlands – but Eva Dolan’s book looks at things from both angles. (Pun intended).

Not only do the crimes in Long Way Home involve both legal and illegal immigrants (in Peterborough) but the detectives in the local Hate Crimes Unit have migrant origins sure to enrage the BNP, the lead detectives, Zigic and Ferreira coming from Serbian and Portuguese backgrounds. Given the current paranoia about Romanian and Bulgarian invasions, Long Way Home is a most timely novel which paints a noirish and painfully depressing picture of Peterborough, or at least certain parts of it as when female detective sergeant Ferreira visits an area long in need of redevelopment: Gap was gone, Topshop was gone. The only new businesses opening up were pound stores and hole-in-the-wall gold dealers. Old-school fences given a gloss of legitimacy with a smart website and some cheap advertising space on Hereward FM. She parked outside Cash Converters.

|

|

The Fabulous Baker (Street) Boys

I for one (not counting about seven million others) was delighted to see the ‘modernised’ Sherlock return to our television screens after a hiatus where its two stars were busy tackling dragons down in Middle Earth.

Whatever die-hard Sherlockians may think of this 21st century take on the sacred Holmes Canon - although all the Sherlockians I know seem to approve and few can dispute that the episode featuring Dr Watson’s wedding was a cracker – I am convinced it has brought a new generation of readers to the original stories, and a generation who will certainly respond to the splendid new editions, originally dating from 1905 and 1917, published by BBC Books last month.

Spoiler Alerts

I have been a great fan of, and advocate for, the ‘Inspector Pekkala’ thrillers of Sam Eastland (a pen-name used by that fine novelist Paul Watkins) since they first appeared in 2010. Set in Russia in the years before and during WWII, our hero Inspector Pekkala begins as a special investigator for Tsar Nicholas, fails to escape after the Bolshevik revolution, is arrested, exiled to Siberia, and then is recalled to investigative duties by a new Tsar – Stalin – on the eve of war with Nazi Germany, a remarkable career trajectory for the period 1916 -1941 when simply staying alive was quite an achievement.

I am loathe to say too much about the plot without falling foulof the ‘Spoiler Alert’ rules of reviewing, but I have a feeling that in the new, fifth, Pekkala book, The Beast in the Red Forest (Faber), author Sam Eastland may be guilty of doing just that himself.

It is a problem with books and characters in a series – especially a series closely linked to historical events – that the author cannot assume that the reader has read the previous titles and therefore has to explain an awful lot of back-story and on-going sub-plots. In doing this in The Beast in the Red Forest, there are definite ‘spoilers’ to the plots of two earlier books which, necessary though they may be, give a rather disjointed feel to the structure – which is already slightly skewed as Pekkala himself does not appear for the first hundred pages, having faked his own death at the end of The Red Moth (as we all knew he did).

Given the complicated core plot of the book (which threatens to spiral out of control in the last third), this is not, I would suggest, the Pekkala adventure which new readers should start with, good though it is (despite the impression I may have given). For once I have to side with those readers whom I have often disparaged as possibly OCD in the past and insist on reading a series in chronological order. With the excellent Pekkala series I recommend starting at the beginning with Eye of the Red Tsar and you’ll soon be hooked.

Lost in Translation

I have recently come across a Spanish edition of (possibly) one of my favourite thrillers by one of my favourite authors and, to misquote the late great Victor Meldrew, I couldn’t quite believe it!

The book, by Geoffrey Household, is Animal acorralado, which I believe means ‘Cornered Animal’ in English and – I’m guessing here – is a translation of Household’s 1939 classic man hunt thriller Rogue Male. The figure on the cover is, however, rather familiar to anyone who remembers that excellent long running (1965-75) TV series Public Eye for surely it is Alfred Burke as the dour private eye Frank Marker.

Double Take

I admit to getting somewhat over-excited when I received the new James Oswald thriller The Hangman’s Song – a third outing for his Inspector Maclean – in its wonderful ‘green Penguin’ livery, which brought back so many memories of much-loved crime novels.

My enthusiasm was curbed somewhat when I realised I was holding an uncorrected proof copy and that the real cover, when the book is published in February, will eschew the iconic Penguin Crime design. Is it churlish of me – am I being a Mugwump, as Reginald Hill would have said – to suggest that the proof version is more appealing? Probably.

Christmas Cheer

I should not really be telling you this, but I belong to a highly secretive elite body of writers known as the S.O.E. which operates within The Guardian newspaper. The annual Christmas party of the S.O.E. is always a treat, whether held in a dusty pub in Clerkenwell or a fashionable cocktail bar near Regent’s Canal, but the problem with secret organizations throwing parties is that one is never sure who will be there.

I was delighted to discover that thriller writer, painter and art historian Reg Gadney was also a member of S.O.E. and that we shared many mutual interests in the worlds of both crime fiction and art, from John Constable to Francis Bacon.

Reg Gadney is also a television scriptwriter of some repute, probably best known for his biopic Kennedy (starring Martin Sheen as JFK) and for his adaptation of Minette Walters’ The Sculptress. In 1989 he also scripted the TV movie Goldeneye – no, not the one with Pierce Brosnan as Bond – but a film about Ian Fleming’s life and his Jamaican house, which starred Charles Dance as Fleming and Julian “Downton” Fellowes as Noel Coward.

And still on a Christmas theme, I felt I must share the splendid card I received from writer and producer Ian Dickerson, author of The Saint on TV and a respected authority on all things Simon Templar.

Ian’s card reminded me that the new Hodder edition of Leslie Charteris’ The Saint in Europe (first published in 1953) comes out at the end of this month. The reissue comes with a brand new Introduction from someone who is far from an authority on the famous character, the fictional bridge between Buchan and Bond, and who discovered Mr Templar’s adventures very late in life. Er….me.

Going Foreign

Yorkshireman David Hewson has written first rate thrillers set in many an exotic location, though never as far as I can think, in his native Yorkshire. In his new novel, The House of Dolls (coming from Macmillan in April), he sets his scene in Amsterdam, though he has had great success with previous books set in Denmark, in Venice, in Rome and in Seville in Spain with his famous debut Semana Santa in 1996.

In many ways, David Hewson is continuing in the tradition of a long line of British crime writers who have chosen to set their fiction in foreign fields with local detective heroes. Robert Wilson (West Africa, then Spain), Michael Dibdin and Magdalen Nabb (Italy), Anna Zouroudi (Greece) and Thomas Mogford (Gibraltar) are among the more recent examples, but the urge to ‘go foreign’ goes back a good fifty years, probably to Nicolas Freeling’s creation of detectives Van der Valk (Dutch) and Henri Castang (French), with an appreciative nod to Spanish detective Juan Llorca created by Delano Ames (an Anglophile American) in 1960.

In 1979 a new Spanish detective, bearing a rather cheeky resemblance to the recently late General Franco, came on the scene in the portly shape of Superintendent Luis Bernal in Saturday of Glory, the first crime novel to appear under the name ‘David Serafin’. Set in the turbulent years known as ‘The Transition’ when Spain moved, sometimes painfully, from Fascist dictatorship to constitutional monarchy, the six Bernal novels published between 1979 and 1988 were noted for their grasp of Spanish customs and history as well as their authentic police procedure.

Saturday of Glory, originally published by the Collins Crime Club, went on to win the Crime Writers’ Association’s John Creasey Award for best first novel, presented to David Serafin by Britain’s leading pathologist Dr Keith Simpson.

Given the depth of local and political colour in the Bernal books, it was somewhat surprising that the author’s first language was not only not Spanish, but actually Welsh, as the pen name ‘David Serafin’ was invented by Professor Ian David Lewis Michael, an Oxford scholar who was born in Neath in South Wales in 1936. As an academic, Ian Michael is best known as an expert on medieval Spanish literature and for his version of the epic Poem of the Cid. He first visited Spain in 1955 while reading Spanish at King’s College, London and has lived there for many years. In 1994 he became the first British-Spanish Foundation visiting professor at the University of Madrid and in 2011 edited a new Spanish version of his debut crime novel Sabato de Gloria.

In December, Ostara Publishing reissued three Superintendent Bernal books in new English versions and as eBooks for the first time under the Ostara Crime imprint, of which I have the great pleasure to be the editor. Normally, this is a spiritually rewarding exercise, for what could be more rewarding than seeing good backs back in print after too long away?

However, I have been given the unsettling news by my friend Count Aleksandr Orlov (who has some experience of such things) that whilst I often refer readers to that most excellent Ostara Publishing website (www.ostarapublishing.co.uk), it seems there is also a website for something called ‘Ostara Publications’ which deals not with crime fiction, but with books which seem to advocate a rather white supremacist view of history.

I would urge my readers not to give this odious site the oxygen of publicity by trying to locate it. For good books and good reading, stick to Ostara Publishing. As my friend Count Orlov would say: “Simples!”

Last Word

From my old and distinguished friend Margaret Maron in America, I received a lovely Christmas present in the form of a charming book of quotations on the subject of Books and Reading. One of the wisest of many wise sayings on the subject is by Witold Rybczynski (a name which would score quite a lot at Scrabble) and goes as follows:

I have always cherished valueless books; that is, books whose chief worth is their simple readability. Page-turners, they are sometimes disparagingly called, as if providing the reader with a reason to turn the page were contemptible, let alone easy.

Whilst admiring the sentiment of the above (although I can think of at least two ‘proper’ novelists who have claimed that their switch to page-turning crime and suspense fiction was because ‘it was easy’) I have to admit that I had no idea who Witold Rybczynski was until I looked him up. He is in fact the Emeritus Professor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and I suppose I should have known that if I hadn’t been engrossed in a serious bout of page-turning.

Other gems from the same source include: The ideal mystery is one that you would read if the end was missing (Raymond Chandler); and, on receiving an unsolicited manuscript, Benjamin Disraeli’s famous quip: Many thanks. I shall lose no time reading it.

I was slightly disappointed not to find myself quoted in the book, or rather mis-quoted and wrongly-attributed, for the saying You can’t tell a book by its cover is listed as an ‘English Proverb’. I really must write to the editor and point out that my original quote was: You can’t tell a book by its cover, unless it’s a Jeffrey Archer…

Happy New Year

The Ripster

|