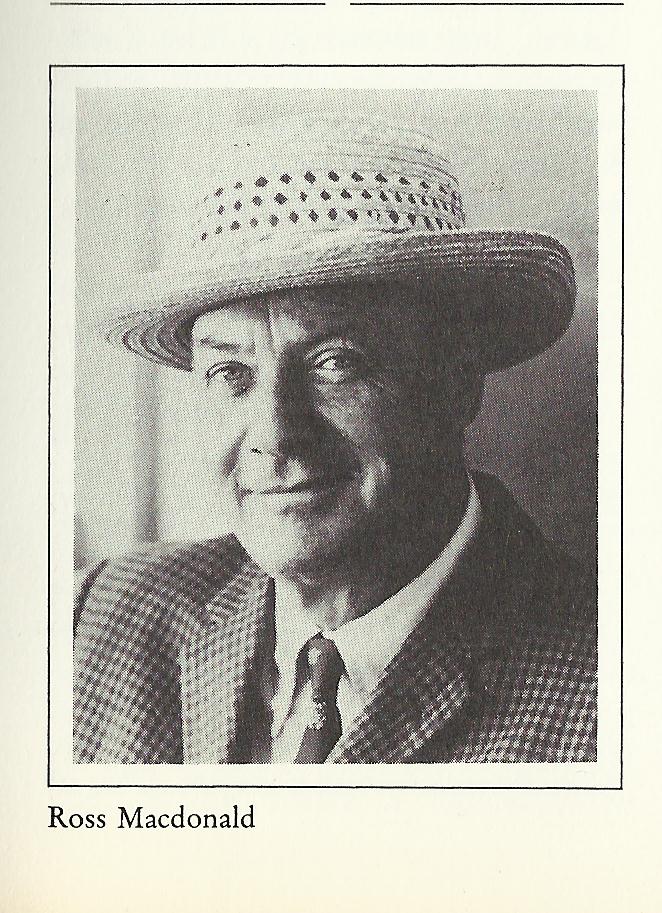

WALTER SATTERTHWAIT is the author of more than a dozen mystery novels and has published two collections of short stories. He is best known for his series featuring Santa Fe private eye Joshua Croft and for light-hearted historical mysteries featuring real historical characters, from Lizzie Borden and Oscar Wilde to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and harry Houdini. A long-time fan of the work of Ross Macdonald, he wrote this introduction to the short story The Sleeping Dog for the June 2010 edition of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, which is reprinted here by kind permission of the editors.

"I counted the number of rooms I had lived in during my first sixteen years," he once wrote, "and got a total of fifty."

As a son, he was born in California in 1915 but lived most of his childhood in Canada. He was abandoned by his father, John Macdonald Millar, at the age of three, and raised partly by his sickly Christian Scientist mother, Annie, and partly by other relatives, including his Mennonite grandparents. In high school, he drank and fought, smoked and stole and gambled, until he straightened himself out and went to work for a year on a ranch. When his father died in 1932, the insurance policy, still made out to his wife, provided her with enough money to buy a annuity that paid for their son’s college. Three years later, when he was twenty, she died of a brain tumor. He spent the next year traveling throughout Europe, bicycling by himself across Nazi Germany. At the University of Michigan, he studied under W.H. Auden and wrote his doctoral dissertation on Samuel Coleridge.

As a husband, he often argued with his wife, Margaret. Sometimes they merely screamed and shouted; sometimes they threw things at one another. Over the years, occasionally, they could not live together; but they could never live apart. By shaping and editing her work, he helped her become a published mystery writer before he became one himself. With the money from a movie sale, she bought their first California house, in Santa Barbara, the town in which they remained for most of their adult life. Collectively, in 45 years together, editing and helping each other, they wrote 53 books.

As a father, he had one child, a daughter. When she was sixteen years old, she went to trial for killing a young boy with the car he had given her. Afterward, he and she both underwent psychotherapy. He maintained, throughout his career, that the therapy had probably saved his life. His daughter, however, was still troubled; and, a few years later, while she was attending University of California at Davis, near Sacramento, she simply disappeared from her room. His frantic cross-country search for her became front page news. After she was found in Reno, Nevada, she went back into therapy, and he went into the hospital with a damaged heart. She died of a brain hemorrhage in 1970, sixteen years before he died of Alzheimer’s. She was only 31.

Over the course of his life, he went by a number of names: Kenny, Ken, Kenneth, Mr Millar. For his first few books, he was "Kenneth Millar." For the next one, perhaps to prevent any confusing of his books with those of his wife (who wrote as Margaret Millar), he used his father’s name, "John Macdonald." Then, to distinguish himself from fellow writer John D. MacDonald, he was "John Ross Macdonald." Finally he was just "Ross Macdonald," the name under which he became internationally famous.

Given all that, it is perhaps no surprise that what he wrote about most often, what seemed to obsess him, was identity. Where other mystery novelists concerned themselves with who done it, Mr. Macdonald wondered why it had happened – howhad individual men or women become who they were, how had they reached a point at which murder, the theft of a human life, appeared not only necessary but somehow inevitable?

His early detective novels were smart, solid, Raymond Chandler clones. His detective, Lew Archer, was a slightly gentler version of Phillip Marlowe; a tad more thoughtful, perhaps, but still quick with a quip or a fist. His cases offered all the standard hard-boiled furniture – corrupt officials, crooked cops, quack doctors, arrogant rich, noble poor, gats and shivs and molls. Starting with The Doomsters in 1958, however, and continuing on through The Blue Hammer in 1976, the books become crowded with outcast and runaway children, with boys and girls, young men and young women, who have been wounded, abused, kidnapped, or, like Mr. Macdonald himself, abandoned.

Over the length of the series, Archer becomes less a sleuth and (as readers and critics have frequently pointedout) more a kind of therapist. Again and again, rooting back through the years, he discovers what it was that had stunted, blunted, twisted the lives of the people he meets, villains and victims alike. The truth, when finally revealed, may not actually set these people free; indeed in some cases, much like the Monopoly card, it sends them directly to jail. But without it, they have no hope of freedom whatever. None of us do, Archer knows.

Mr. Macdonald wrote a spare, intelligent, unadorned prose that was always capable of a heart-breaking, seemingly off-hand beauty. Often coloured, like Archer himself, by melancholy and foreboding, his descriptions of the California countryside can be haunting. He gives it all to us: the cramped cottages, the elaborate private estates, the canyons and the hills, the forest fires, the oil slicks, the bowl of blue sky arching over the flat hammered blue of a Pacific Ocean that both Archer and Macdonald loved.

And the man could plot like a demon. The books are driven not only by Archer’s deepening sympathy, but also by his growing sense of urgency. Almost always, someone is missing, or someone is threatened, time is slipping away, doom is gathering around the next corner or beyond the next mountain. We watch as Archer desperately tries to prevent it from swooping down and consuming us all.

Like most Macdonald fans, I think that all the later Archer novels are terrific. But if I were slammed up against a wall, slapped around, and forced to pick a favorite, I would probably pick The Chill. "The surprise with which a detective novel concludes," he once wrote, "should set up tragic vibrations which run backward through the entire structure." The surprise at the end of The Chill does exactly that, and then some.

His story "The Sleeping Dog" was written in the mid-sixties, after he had found his voice and his purpose.

It’s one of the last short stories he finished; after writing it, he was basically too busy writing novels and becoming famous to deal with short stories.

As good as the stories are, and some of them are excellent, I believe that he showed more of his real strengths in his novels.

Back then, everyone seemed to know about the books. Two of them were reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, one by William Goldman, the other by Eudora Welty. He was on the cover of Newsweek. Throughout the seventies, he was probably the best known American mystery writer in the world. That he is pretty much unknown today, only thirty years later, is fairly depressing.

A few critics have maintained that Mr. Macdonald kept writing the same book. Well, maybe so. But I think that, in a sense, all writers keep writing the same book. It’s just that some of them start with a great book, and keep getting better at it.

online

online what to do when husband cheats

website

open cost of abortion pills

walgreens printable coupon

ravithkumar.com walgreens coupon code for photos

I cheated on my husband

site wives who cheat

temovate tube

link furosemide 40mg

tretinoin 0.025%

open ventolin pill

coupons for drugs

fyter.cn viagra coupon 2016

how much does it cost for an abortion

read medical abortion pill

prescription discounts cards

open free prescription discount cards

naltrexone alcohol side effects

open buy naltrexone