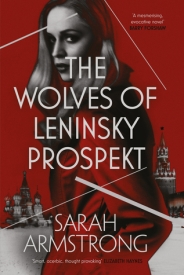

There are some jobs which just seem to suggest spying. Among the most obvious is any position in a foreign embassy, and this is the association I drew on in my first Moscow Wolves novel, The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt. My protagonist, Martha, has entered into a marriage of convenience with a diplomat working at the British Embassy in Moscow. Martha doesn’t work both because she doesn’t need to and because wives were not encouraged to. From a writing perspective, this freed her up to explore Moscow at her leisure, and allowed me to explore it too. Martha is never quite sure whether her husband, or any of his colleagues, are more than diplomats. What Martha never doubts is that at least one of them must be a spy.

This is an assumption which, like most speculation about spies, has been fed by novels and films. Autobiographies published by agents who have defected confirm that it isn’t a lazy stereotype, it is indeed based on fact. And yet, when it comes to the world of spies, as Mick Herron has exploited in his Slough House series, no one can disprove the facts you make up about spies. The world of spying is a closed one, and that allows writers all kinds of latitude.

This is an assumption which, like most speculation about spies, has been fed by novels and films. Autobiographies published by agents who have defected confirm that it isn’t a lazy stereotype, it is indeed based on fact. And yet, when it comes to the world of spies, as Mick Herron has exploited in his Slough House series, no one can disprove the facts you make up about spies. The world of spying is a closed one, and that allows writers all kinds of latitude.

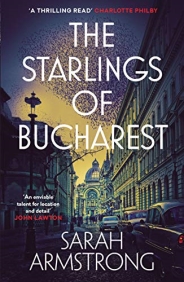

For the sequel to The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt, I wanted to explore different types of work that might fit into the world of espionage. One of the first things I do when starting a new novel is to look up what happened in the year and place I’ve chosen. In 1975 Moscow was host to the Soviet International Film Festival. In The Starlings of Bucharest, I decided that my protagonist, Ted, would be an accidental film critic with aspirations to become a news reporter. A job as a reporter would be a useful cover for a spy but it felt a little too obvious, so I resisted giving Ted this job. Instead, the idea of Ted making a temporary visit to Moscow was a better solution as it provided a way to experience the city which contrasted directly with the months that Martha lived in her flat in the first novel. While researching the range of film festivals across Eastern Europe, it also struck me that being a film critic had huge potential for covert meetings and socialising with people from suspect places in a way which would often be difficult to observe.

The film festivals of the 1970s were highly organised international affairs showing films from dozens of countries in dozens of languages. This meant that translators became a crucial part of the festivals too, and I found some fascinating pieces written by Elena Razlogova which discuss the simultaneous translations which enabled the Moscow International Film Festival, and other international festivals and film tours, to take place. Four of the translators that Razlogova discusses are her relatives, and this gives her discussion of live film translation some fabulous and telling details – often the film had not been seen before, let alone a script provided. The skills of great film translators were widely celebrated, but I was most interested in the power they held. Any translator sitting between two people who don’t share a language has the power to bend the conversation in any direction they like. And if one of the people does, in fact, understand what is being said by the other, the transfer of power becomes even more interesting.

The film festivals of the 1970s were highly organised international affairs showing films from dozens of countries in dozens of languages. This meant that translators became a crucial part of the festivals too, and I found some fascinating pieces written by Elena Razlogova which discuss the simultaneous translations which enabled the Moscow International Film Festival, and other international festivals and film tours, to take place. Four of the translators that Razlogova discusses are her relatives, and this gives her discussion of live film translation some fabulous and telling details – often the film had not been seen before, let alone a script provided. The skills of great film translators were widely celebrated, but I was most interested in the power they held. Any translator sitting between two people who don’t share a language has the power to bend the conversation in any direction they like. And if one of the people does, in fact, understand what is being said by the other, the transfer of power becomes even more interesting.

In The Wolves of Leninsky Prospekt, I introduced the idea of layers of communication, of someone secretly trying to communicate messages through the medium of fairy tales. The idea of hidden meanings within words is something which fascinates me. In The Starlings of Bucharest, the same power and influence comes from the ability to speak more than one language. In spy novels there are many ways to listen into conversations, with tapped phones and bugs in lampshades, but no one can spot and remove language skills. As superpowers go, it’s a pretty easy one to access, but one which many of use never bother to acquire. At least, that’s what we tell people.

Read SHOTS’ review by Sarah Townsend of The Starlings of Bucharest HERE

Published by Sandstone Press (22 April 2021) pbk/eBook