Take two extremes.

On the one hand, Jean Moulin, a prefect who refused to comply with the Occupiers from the outset of the Occupation and who was dismissed from the Vichy government. He became the first President of the National Council of the Resistance and is regarded as one of its heroes, both for his attempts to unify the Resistance under de Gaulle and for the bravery of his actions.

On the other, Robert Brasillach, editor of a Fascist newspaper, who embraced collaboration with the Occupiers. He turned against the Vichy regime to espouse more committed support of Nazi polices. He published the names and addresses of Jews who had gone into hiding, supported the German militarisation of the Unoccupied Zone and signed a call for the summary execution of Resistance members.

There are no nuances here. One was an absolute defiance of collaboration with the Nazis, the other was complicity to the core. But these were extremes – not isolated cases but extremes. The vast majority of the French population under the Occupation fell somewhere between the two, along a spectrum of complicity and defiance that was as shifting and vague as the two cases above were distinct and undeniable.

One of the questions to ask is how you define collaboration and resistance. If you were one of the few to keep your job at the Renault factory on the outskirts of Paris, but you were forced to produce vehicles for the German war effort, did that make you a collaborator? The alternative was unemployment, hunger and hardship.

But say at that same factory, you worked slowly, was that resistance or a form of resistance? You “lost” some of the parts you were manufacturing, or you deliberately spoiled a few parts so they were wasted. Or you damaged them in a way that they would later hinder the performance of the finished vehicle. Or you did something to the production line that caused disruption for a few hours or even days. At what point does collaboration become resistance?

Apply this to every job, every facet of life. In our case, a cop. Eddie Giral, the detective in the Occupation series, is forced to work with Hochstetter, a major in German intelligence. He gets away with what he can, but he also has to rely on Hochstetter’s support to see justice done, such as it is under the rules of the Occupation. There’s give and take on both sides. There’s complicity in what Eddie does to survive, but there’s also duplicity. He uses and is used, forced into both collaboration and resistance. They are dilemmas that will haunt him throughout the Occupation, and eventually come back to haunt him even more.

There were nuances in the act of resistance. Very broadly, the Communists chose direct action, killing German soldiers and sabotaging installations, no matter the retaliations taken by the Occupiers. The Gaullists saw their role as biding their time, building up a secret army that would rise when the Allies invaded. Each distrusted the other’s interpretation of resistance. Did the person who took up a printing press resist any less than the one who took up a rifle? Sheltering a Jewish family and sabotaging a German convoy were no less of an act of bravery than the other – each carried the same punishment.

After the libération came the épuration – the purge – when old scores were settled and where the nuances of complicity became more deadly. Retribution in the aftermath of victory over the Nazi Occupier was unequal at best. Mob rule found its favourite victim in the collabos horizontales, women who had had sex with Germans, although this was usually reserved for working-class women or sex workers, many of the latter forced into this work through hunger and unemployment. Not all of those who collaborated were convicted, not all those who resisted were saved. Intellectuals and artists who had been deemed to have collaborated paid a higher price with their careers – and sometimes their lives – than business owners and bureaucrats.

And the two examples at the start? Jean Moulin and Robert Brasillach? They were both executed. Jean Moulin by the Germans after brutal torture, Robert Brasillach by a French court after the epuration. The price they paid, the same.

And Eddie? The police came in for mixed treatment. During the Occupation, the French police were forced to do the Nazis’ dirty work for them. Some of them did so willingly, others fought back in whatever ways they could. As a whole, with a few exceptions, the complicity of the police under Nazi rule was swept under the carpet for decades, or the same imbalance of treatment in the purge was meted out as it was to others. A prestigious detective – possibly the inspiration for Simenon’s Maigret – who had solved a serial killer case was charged, then acquitted, but never worked again.

So where does that leave Eddie? That’s for me to work out over the course of his story. I’m as nervous about it as he should be.

Read Michael Jeck's review here

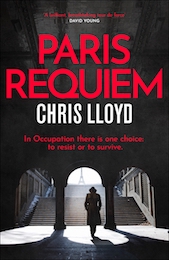

Paris Requiem by Chris Lloyd

Orion 23 February 2023 (Hardback, £18.99)