For some, writing is a form of therapy but author Kia Abdullah uses it for revenge. Here, she tells us why villains from her life have ended up in fiction.

The tiny village of Reeth is one of the prettiest you will ever see. Located inside the Yorkshire Dales National Park, it sits in a natural amphitheatre of classic English views: green valleys, fellside fields and meadows of grazing sheep. I know this because I visited the village in 2018 ahead of a move to the country. My husband and I fell in love with a particular stone cottage tucked away in a Shire-like courtyard. Sure, there was a hole in the roof and the bathroom was smaller than a thimble, but this was our rural ideal.

As we left the cottage after our first viewing, our would-be neighbour – a grey-haired gentleman with a cantankerous manner – came over and asked where I was from. When I told him that I was from London, he waved impatiently and said, “You know what I mean.”

I smiled politely and told him that my family was from Bangladesh but that I had been born and raised in London. As we talked, a young bull terrier bounded up to him. “Her name is Lola,” he told me, bending down to pet her.

Then, completely deadpan, he added, “She was a showgirl.”

I laughed out loud – a hearty, genuine laugh – and he graced me with a grin. It seemed that by recognising the words to the famous Barry Manilow song, I had proven something to him. I was not a peculiarity of which to be suspicious but someone that had a chance of fitting in.

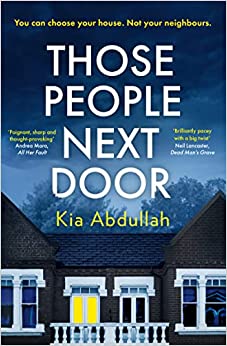

I never did move to Reeth but that exchange stayed with me. To me, it said something subtle but incisive about prejudgment, about belonging, about tribalism and acceptance. It’s why I repurposed this anecdote for my new novel, Those People Next Door.

Set in a safe, suburban development in the outer reaches of London, the novel follows Salma Khatun, a teacher who has just moved to the area with her family. Soon after arriving, she receives an invitation to a neighbourhood barbecue where she meets her next-door neighbour, Tom (who does indeed have a dog named Lola).

Tom is friendly enough but the next day, Salma spots him uprooting the anti-racist banner stuck in her plant pot. Salma chooses not to confront Tom. Her family are new there and she doesn’t want to cause a fuss. Quietly, she takes the banner inside and puts it in her window instead – but the next morning she wakes up to find her window smeared with paint. This time, she does confront Tom who reacts with hostility. Things begin to escalate and soon it becomes clear that somebody is going to get hurt.

Writers often say that fiction is a form of therapy, especially when it deals with social conflict. I would go one step further and say that it’s a form of revenge. While Lola’s real owner got off lightly in Those People Next Door, there are others from my life that have been painted in a less flattering light.

When I talk in the novel about Jay, Salma’s accountant ex who stole two thousand pounds from her after they broke up, I’m drawing on real-life experience. Like Jay, my real-life villain did not think I’d have the gumption to report him to the police. Like Jay, he called me in a panic and begged me to drop the complaint. Like Salma, I got my money back fairly sharpish.

Later in the novel, I talk about Helen, an old colleague of Salma’s. Helen is spiteful and petty in her efforts to undermine Salma. She excludes her from the BCC field when sending important emails, or changes the location of a crucial meeting and updates everyone but Salma. I modelled Helen on a real former colleague whose behaviour verged on bullying. I won’t name her but I know that if she should ever read the novel, she will recognise herself.

So too will the nepo baby whose sloppiness almost cost me my first dream job if she ever picks up my next novel. As will the man whose “shiny suit makes his neck fat crease” if he ever picks up my debut.

Anonymity is key to using fiction as revenge. My intention is not to reveal a villain’s identity. Rather, it’s to make them take a look at themselves; to hold up a mirror and say “this is who you are”.

Perhaps this is a bit grandiose. In reality, these real-life villains likely moved on a long time ago. I’d be surprised if they give me a second thought let alone read my novels, but I also know that my revenge is there, like a rotten easter egg, waiting to be discovered – and that’s enough to satisfy me.

Sometimes I wonder how I would feel if I read a fictional villain that I recognised as me. My instinct is that I’d be flattered. The fact that someone has immortalised me appeals to my vanity, but of course it depends on the type of villainy. If I was truly wrong – as I have been many times in my life – and my behaviour was genuinely hurtful, then I’m certain I would feel chastened. If you’re a decent person, being called out for stealing, cheating or bullying should feel awful. I’m sure that’s how I’d feel and I hope that’s true of my villains too.

Until then, I’ll leave them – and you – with a familiar warning: Don’t mess with writers. We’ll describe you.

THOSE PEOPLE NEXT DOOR, 3rd August 2023, Pbk HarperCollins HQ

read SHOTS' review