|

RIPSTER REVIVALS #12

An occasional column of ramblings around the world of (mostly) crime fiction and thrillers.

|

Christmas Viewing

For the umpteenth time I enjoyed the 1957 Western The Tall T, very much a vehicle for its star Randolph Scott but worthwatching for the performance of the always-excellent Richard Boone as the charismatic baddie. What I had not registered, to my eternal shame, until now was the fact that the screenplay was based on a 1955 ‘novelette’ in Argosy Magazine called The Captives by no less a maestro than Elmore Leonard.

However, my viewing highlight came on Boxing Day with BBC2’s scheduling of a real feast of favourite movies: The Big Sleep followed immediately by Casablanca followed, with barely time to draw breath, by The Magnificent Seven – the ‘original’ 1960 remake, not the more recent travesty. Best Boxing Day EVER!

However, my viewing highlight came on Boxing Day with BBC2’s scheduling of a real feast of favourite movies: The Big Sleep followed immediately by Casablanca followed, with barely time to draw breath, by The Magnificent Seven – the ‘original’ 1960 remake, not the more recent travesty. Best Boxing Day EVER!

I must also award five stars to the French series I discovered by accident, Les Espions de la terreur; a dramatic reconstruction of how various security services (often in competition) investigated the co-ordinated terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015 by Islamist militants.

Keeping Up With The Times

Full marks to Mark Sanderson, the esteemed crime critic of The Times for his round-up of Christmas-themed crime fiction (though he did overlook one notable seasonal title) in December, if only for his turn of phrase when reviewing the anthology Murder By Candlelight edited by Cecily Gayford for Profile Books, praising the assembled stories for “making this collection like Cyd Charisse, a perfect stocking-filler.”

Year Ending

Last year ended with the sad news, just before and after Christmas, of the deaths of veteran thriller writer Brian Freemantle, aged 88, and veteran crime writer Kinn McIntosh, better known as Catherine Aird, aged 94.

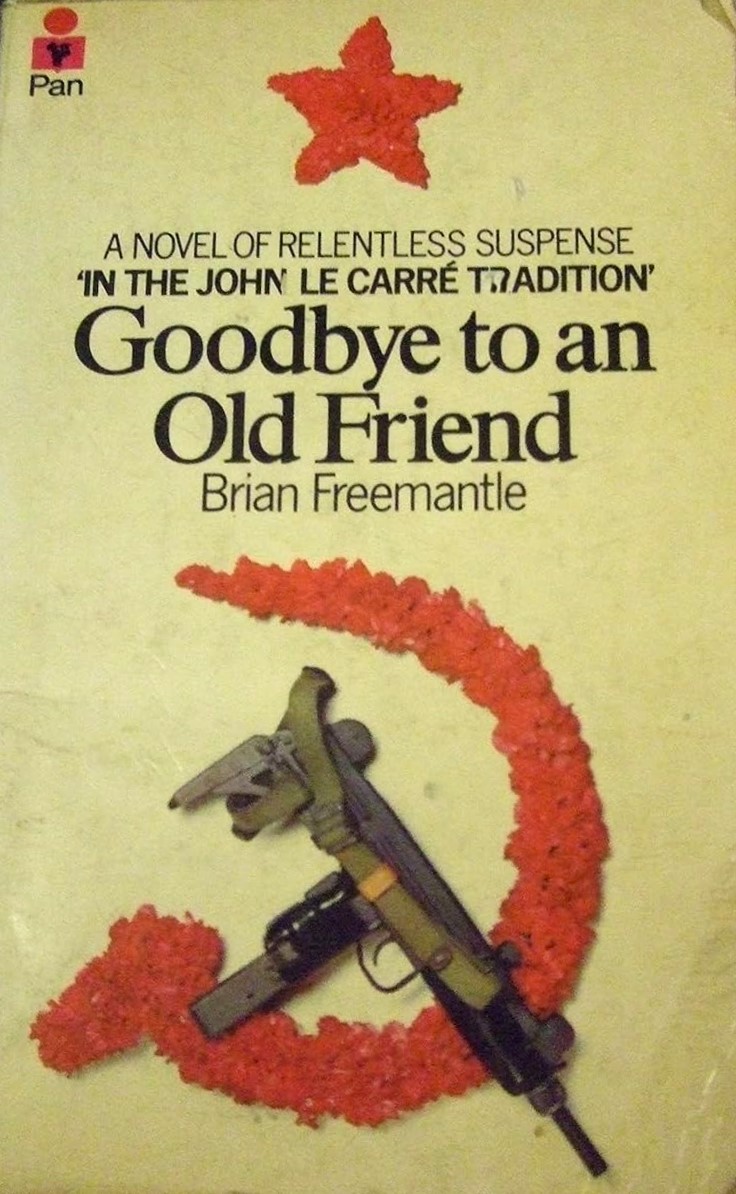

I had not realised how prolific an author Freemantle was, writing fiction in several genres (and under at least two pen-names) and non-fiction, but he is perhaps best known for his sixteen or seventeen book series featuring Charlie Muffin, the downbeat British spy whose favoured footwear were always Hush Puppies. A distinguished journalist and foreign editor of the Daily Mail, Freemantle’s first foray into spy fiction Goodbye To An Old Friend in 1973, brought him favorable comparisons with John Le Carré and Anthony Price, no less, claimed he was the natural ‘heir to Mr Deighton’. The book was optioned for filming, with Freemantle writing the screenplay, but never made although his Charlie Muffin character did make it into a TV movie in 1979.

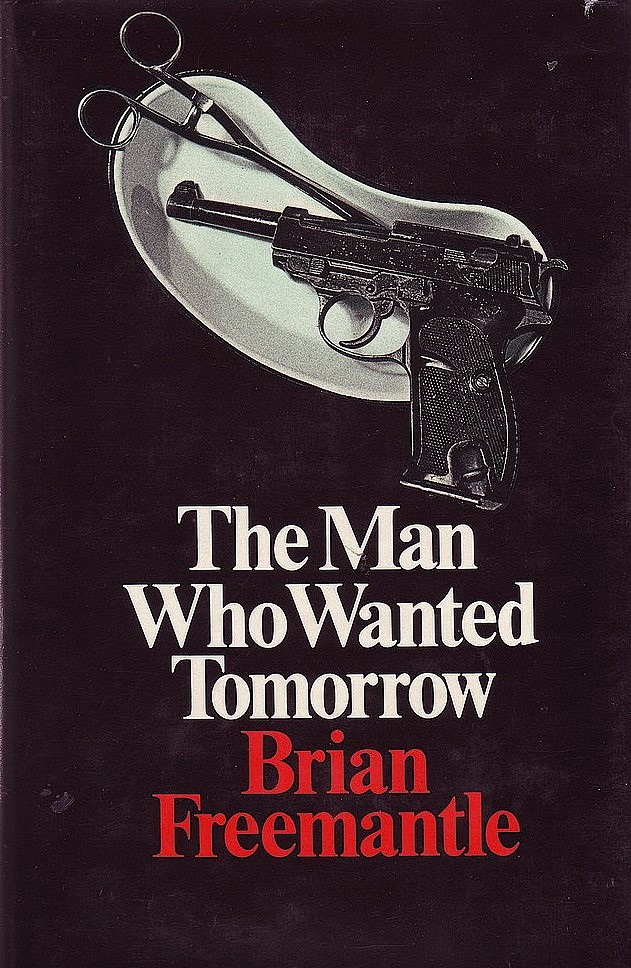

I only met Brian Freemantle once, many years ago, and was able to tell him how highly I rated his 1975 thriller The Man Who Wanted Tomorrow which was sadly overshadowed on publication by the blockbuster sales of The Eagle Has Landed.

I first met Catherine Aird thirty years ago when we seemed to run into each other at events organised by the Dorothy L. Sayers’ Society, often appearing on the same bill. In between the panels we discovered that we had both been born in Huddersfield and had spent childhoods no more than half-a-dozen miles but twenty-five years apart. It came as quite a surprise to both of us as I had always associated Kinn (a shortened form of a Scottish family name Kinnis) with Kent, where she lived for most of her life and which was the blueprint for the county of Calleshire she invented for her crime fiction. Likewise, based on my early ‘Angel’ books, she assumed I was a Londoner, mostly thanks to my constant references to The French House in Soho. She once sent me a lovely little coloured print of the Dean Street pub with the news that she had just had tea with an old friend, the sister of Gaston Berlemont, the pub’s famous landlord.

She always claimed, at least to me, that she had taught herself to read by copious borrowings from the local library in Huddersfield and by reading whilst walking to and from school through Greenhead Park, one of her not-so-guilty pleasures being the ‘Saint’ books of Leslie Charteris. We shared a common interest in the coal-mining industry – she was familiar with the mining villages nearby, including the one my family came from as well as the associated brass bands – which she pursued in studies and articles on the Kent mining industry.

A prolific writer and editor on matters of local history as well as a crime-writer, she also co-authored, in 1978, an article for the medical journal The Practitioner with her doctor father Robert McIntosh, on a possible explanation behind the black propaganda spread by those devious Tudors about ‘crookback’ Richard III.

In one of my early ‘Angel’ books, I appropriated her name (almost) for a character, Kim McIntosh, a topless, Page 3 model. Catherine responded in her next Inspector Sloan novel, with an acknowledgement in the plot to ‘the late Professor of Archaeology, Mike Ripley’. She was a regular reader of my Getting Away With Murder column and often suggested titles to add to my to-be-read pile.

Non-Fiction

My non-fiction read of the year (so far) is Money by Irish economist David McWilliams [Simon & Schuster], which is a history of money – coins, paper and beyond – but is sub-titled as ‘a story of humanity’.

It is a fascinating, and very readable, history ranging from Sumerian lines of credit 1000 years BC to Ancient Greek and Roman coinage and via the influence of Arabic mathematics, to the Florin of Renaissance Florence to the establishment of international trading routes and national banks by the Dutch and British. And then the almighty American dollar courtesy of Alexander Hamilton and though McWilliams resists the urge to write in hip-hop couplets, that section did give me the urge to re-read Gore Vidal’s Burr, especially having worked out that it is forty-nine years since I first raved about it.

Money is not quite perfect as the author tries too hard to be down with the kids (Peter the Great “rocked up” to Amsterdam in 1697) and I was always taught that the ‘discovery’ (looting) of vast amounts of gold and silver in the New World led to massive inflation in Spain, though this hardly rates a mention. The Anglo-Dutch wars of the 17th century are also treated rather skimpily, even the naval battle of Sole Bay which holds a special place in the hearts of all drinkers of the fine ales of Adnams of Southwold.

But these are minor niggles; it really is an enthralling story and I learned a lot, not the least being the derivation of the word ‘dollar’ and the fact that Hitler and Stalin (under the name Stavros Papadopoulos) once lived seven miles apart in Vienna in 1913.

The author, being Irish, is big on the story of Sir Roger Casement and no fan at all of the British colonialism, though that’s understandable. He is also illuminating on the economic (Gold Standard v. Silver Standard) subtext to The Wizard of Oz and the significance (in the original book) of Dorothy’s shiny silver slippers treading that yellow brick road.

A Littell Bit Of Magic

I could never really understand people who could only read a series of novels in the order in which they were written. Similarly I was mystified by one crime and thriller fan – an intelligent person of taste and judgement – who refused to read one of my ‘Mr Campion’ novels in case he liked it, which would thus require him to buy and read the other eleven and he simply did not have the time to invest in such a compulsion. Perhaps he was just letting me down gently.

Anyhow, the point I wanted to make was that I discovered the spy stories of Robert Littell in 1996 when I was sent Walking Back The Cat to review for the Daily Telegraph and then had the pleasure of reviewing his majestic, 900-page fictional history of the CIA, The Company, for the Birmingham Post, where I opined that Littell was “the nearest thing America has to a John Le Carre”.

.jpg)

Having discovered him, I have read a Littell novel wherever I have found one; by no means all of them and certainly not in any order which will confound the obsessives among us. I have recently acquired a copy of his 1991 thriller An Agent In Place and am really looking forward to it, safe in the knowledge that I will not be disappointed.

Littell, now 90, who has lived in France for several US presidencies, is a master craftsman and has a new novel, Bronshtein In The Bronx (about Trotsky’s visit to New York in 1917), out this month from Soho Press. As I have not been asked to review this one, it will go to the top of my Have-To-Buy list.

Finally...

I have finally got around to reading a novel originally published in 1988, the year my first novel appeared, not that the two have anything else in common.

Alan Furst, who is best known for his historical spy thrillers, many set in locations Eric Ambler would have appreciated, has been a favourite author of mine for some time yet I have only just discovered his Night Soldiers and think it might be his masterpiece and one of the best spy stories of the last century. Certainly it would make my personal top ten.

Opening in Bulgaria in 1933 just as a Nazi near neighbour begins to exert its influence, young Khristo Stoianev sees his brother killed by fascist street thugs and turns, for salvation, to Russian communism. In Moscow he is recruited into the NKVD as a trainee agent, showing considerable aptitude despite the totally ruthless training regime. Khristo is given his first mission, to Catalonia in the midst of the Spanish civil war ostensibly to aid the Republican cause, but in reality to root out ideological ‘traitors’ among the numerous left-leaning groups supposedly on the same side. When he learns he too is the target of a Stalinist purge, he decamps to Paris and creates a new identity for himself. But France, on the eve of World War II is not likely to be a safe haven for a spy on the run.

Night Soldiers is a tour-de-force of storytelling, political history and spy tradecraft, which doesn’t stint on the underlying paranoia of the professional agent, especially when it is clearly justified. The early scenes in Bulgaria and Moscow are cleverly done, the Spanish section, centred on the siege of Madrid (and its ‘Fifth Column’) is packed with examples of bravery, deprivation, brutality and betrayal and in Paris, our reluctant hero discovers that a spy’s life is not one from which you can retire quietly.

Con Molte Grazie

I am grateful to Bitter Lemon Press for introducing me to a pair of Italian crime writers I was previously unaware of: Carlo Fruttero (1926-2012) and Franco Lucentini (1920-2002), a writing and editing duo who always styled themselves Fruttero & Lucentini.

My introduction came via Bitter Lemon’s publication this month of Runaway Horses, the first English translation of Fruttero & Lucentini’s 1983 novel Il Palio delle contrade morte and I was immediately intrigued, as anyone who has ever been to the Tuscan city of Siena would be, by the words ‘contrade’ (the various ancient neighbourhoods, each with its own heraldic livery) and ‘Palio’ (the famously chaotic horse race between them which takes places in the main piazza).

I do not know if Runaway Horses is typical of F & L’s crime writing output as it is certainly not a conventional detective story. A Milan lawyer and his wife travelling through rural Tuscany during a violent storm take a wrong turn and end up seeking shelter in a strangely isolated villa populated by an eccentric cast of people who all have an interest, if not a dubious financial stake, in the next Palio race to be run in nearby Siena. Among the villa’s residents is a champion Palio jockey with an anti-social habit of biting delicate parts of female anatomy, who is relatively quickly brutally murdered – or is he?

Basically the book is a satire on the morals and values of the Italian rich as reflected in the crumbling marriage of the Milanese lawyer and the greed and corruption surrounding the medieval Palio. Above all, it is a love letter to Siena and its traditions, which are described in fascinating, often acerbic, detail. (There are seventeen contrade in Siena though not many Sienese can name them all straight off.)

I am doubly grateful to another Italian crime-writing duo, old friends Michael Jacob and Daniela De Gregorio (a husband-and-wife team who write as Michael Gregorio), for sourcing a copy of the original Italian edition for me. I will treat it as homework in my continuing attempts to learn the language. I suspect it will keep me busy for some time.

New From Down Under

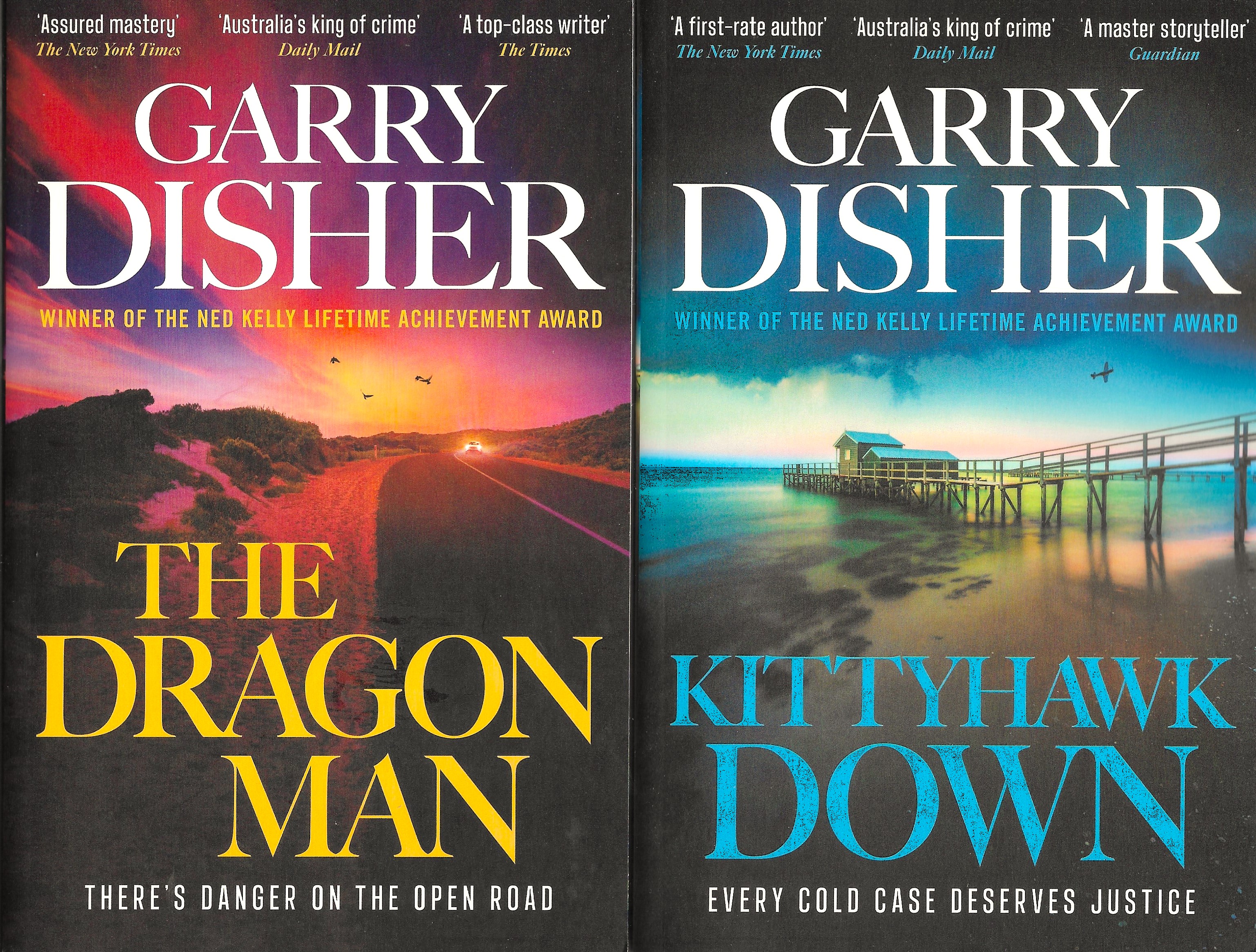

Garry Disher is a highly respected, multi-award winning Australian crime writer and has been called the Godfather of the school of ‘Outback Noir’ (if only by me, just now).

This year, Viper are releasing four of his Inspector Hal Challis mysteries, set in the Mornington Peninsula south of Melbourne. Indeed, Disher’s Challis books were known as the Peninsular series, although the area is probably better known for Pinot Noir than for Outback Noir.

The first two reissues, available in February, are The Dragon Man and Kittyhawk Down.

In July, Viper will release two more Hal Challis cases, both being published in the UK for the first time: Snapshot and Chain of Evidence. All four are worth checking out if you like a solid police murder mystery as you sip your Pinot.

Chinese Crackers

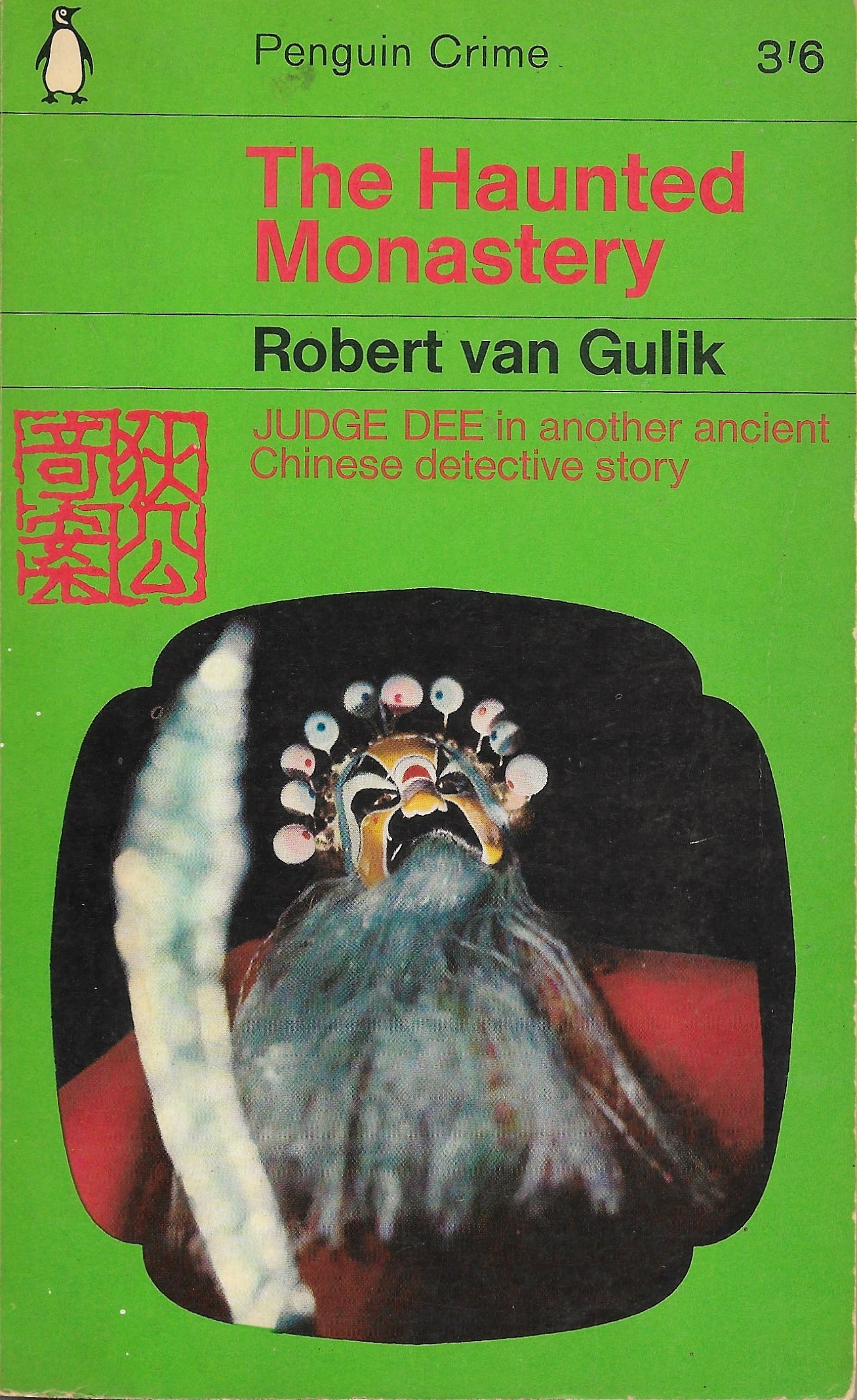

I discovered the exploits of Judge Dee – the Sherlock Holmes of the Tang Dynasty – as a schoolboy. The fact that they were written by Robert Van Gulik, a Dutch diplomat and orientalist, just seemed to add another layer of exoticism to reading about crime fighting in China at the turn of the 8th Century.

Blending the legend of a real historical character (probably a travelling magistrate) with his expert knowledge of ancient China and its superstitions, Gulik wrote four or five volumes and even illustrated them with charming line drawings of locations and of Dee Jen-djieh himself in full sleuthing mode. Dee, naturally, had a ‘Watson’ named Gan Tow and a TV series of six stories was made in 1969. Among the cast of one of them was a young Timothy Dalton in his pre-James Bond days.

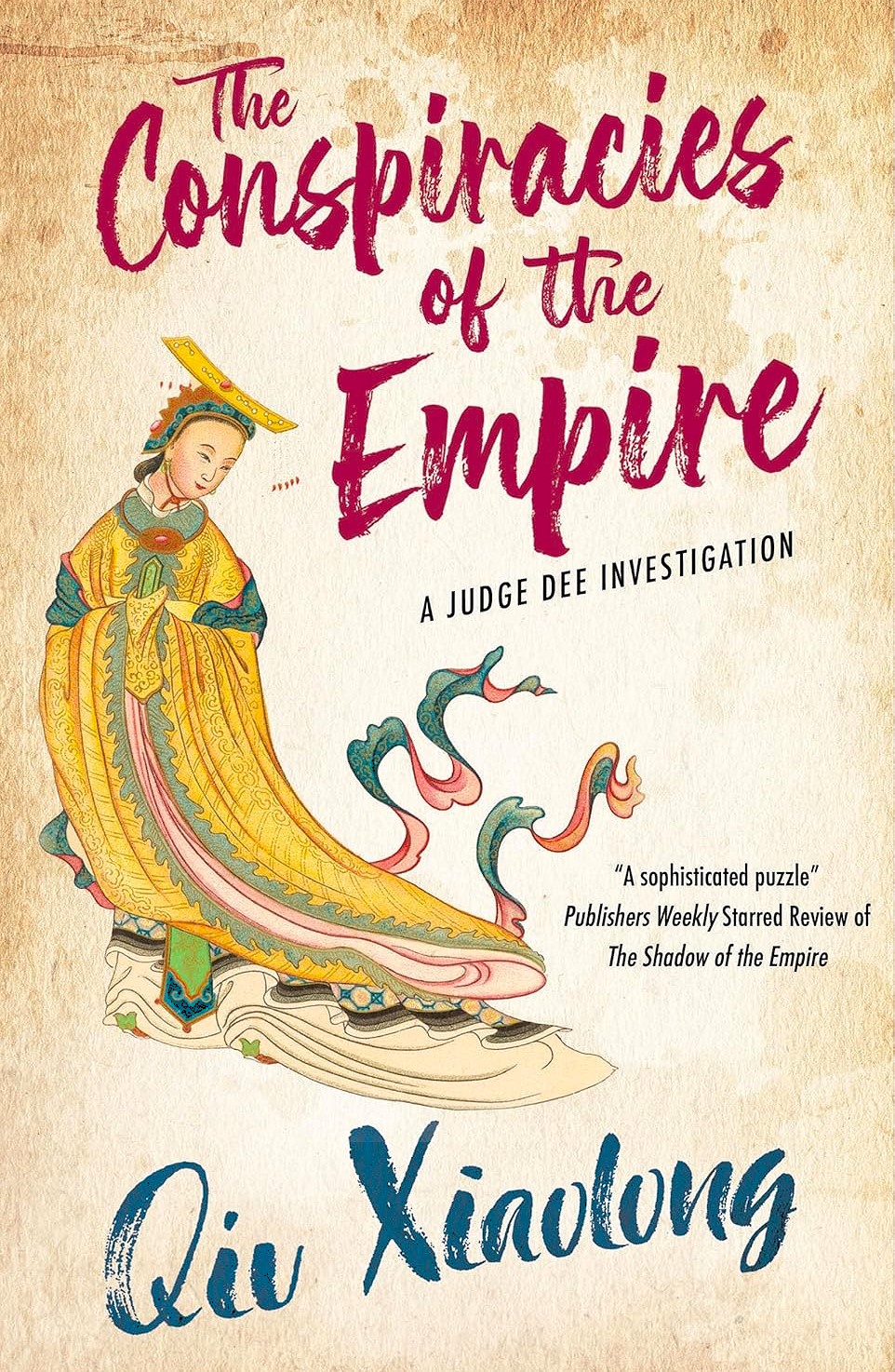

I had no idea, until recently, that the Judge Dee stories were getting a second lease of life thanks to Chinese-American writer Qui Xialong, the author of the contemporary mystery series featuring Shanghai cop Inspector Chen.

The Conspiracies of the Empire was, it seems, the second of his Judge Dee resurrections and was published by Severn House late last year.

From the To-Be-Read Pile

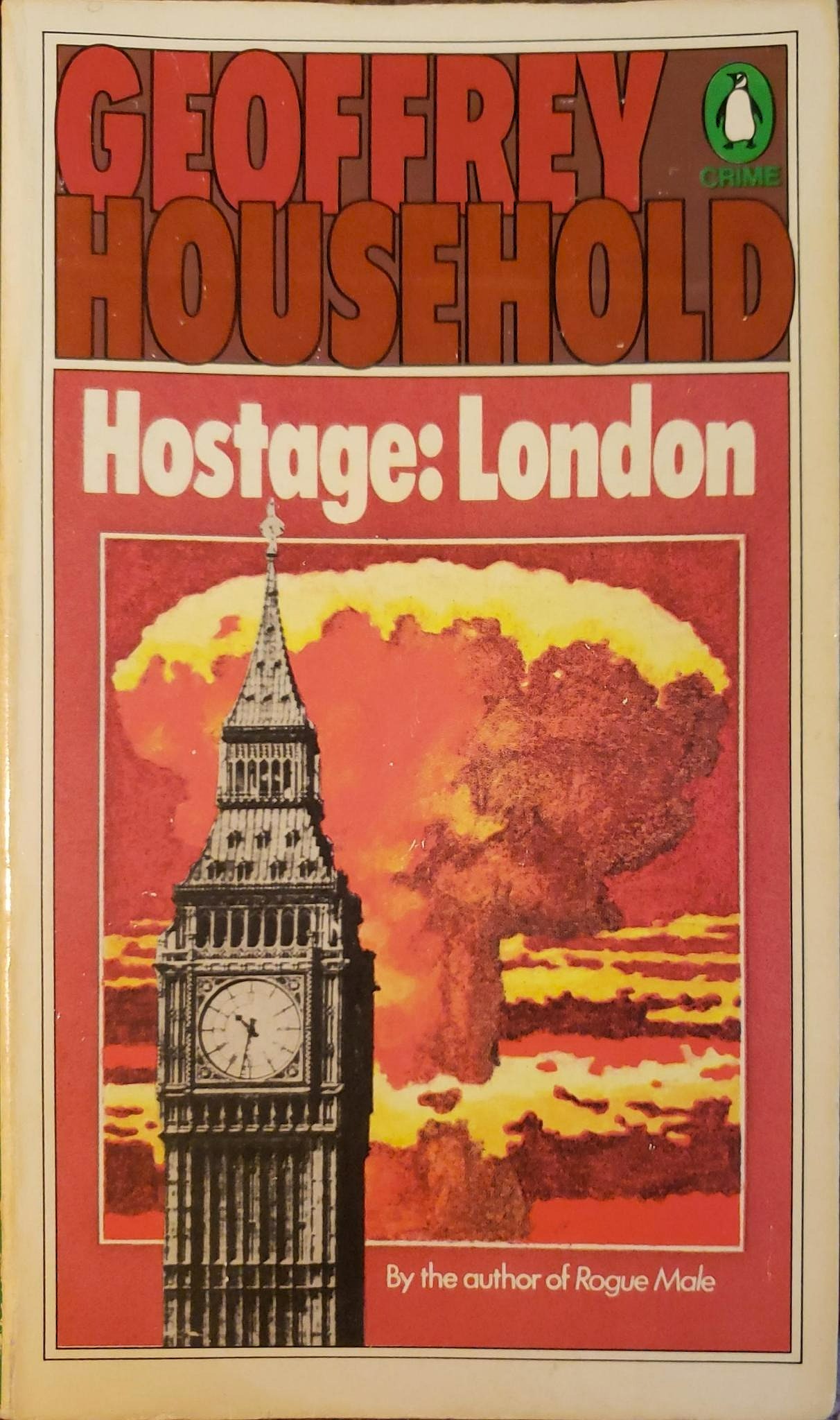

I am steadily making inroads into my groaning To-Be-Read pile, which currently stands at 265 novels, although this pile does not include non-fiction or an even larger Must-Re-Read pile. Part of the joy in this exercise is discovering an unread title by a treasured author, as I did last time with Gavin Lyall. This time it was Geoffrey Household, a long-time favourite of mine and I did have the honour of editing reissues of two of his thrillers – Watcher in the Shadows and Rogue Justice– which had been disgracefully out of print for far too long.

I had not, however, read Hostage: London one of his later novels, first published in 1977. The book is narrated by anarchist revolutionary Julian Despard who begins to have second (third and fourth) thoughts about the international organisation MAGMA to which he has offered his services as a professional terrorist. When he discovers that MAGMA have acquired the means and material to make a nuclear bomb (on a farm in the Cotswolds!) and then plant it in London, he thinks things have gone too far and begins to sabotage the plan to hold the city hostage.

I had not, however, read Hostage: London one of his later novels, first published in 1977. The book is narrated by anarchist revolutionary Julian Despard who begins to have second (third and fourth) thoughts about the international organisation MAGMA to which he has offered his services as a professional terrorist. When he discovers that MAGMA have acquired the means and material to make a nuclear bomb (on a farm in the Cotswolds!) and then plant it in London, he thinks things have gone too far and begins to sabotage the plan to hold the city hostage.

Although there are numerous points when a suspension bridge of disbelief is required, and there are seemingly endless debates about ‘Christian anarchism’ and it’s never very clear what MAGMA hope to achieve, our anti-hero Despard shows himself to be a true Household creation when alone and hunting, or being hunted (shades of Rogue Male), both across country and in urban London. Trained in guerilla warfare (in Uruguay), Despard is a dab-hand with the knife he carries in a shoulder holster and deadly accurate with a Lee Enfield rifle when push comes to shove.

In a violent finale, reminiscent of the suicide mission in Household’s superb Rogue Justice, London is saved but Despard isn’t. A curious jumble of political satire with surreal touches (a militant female anarchist using a false beard as a disguise to fool the police) and brutal violence, which certainly has its moments.

*

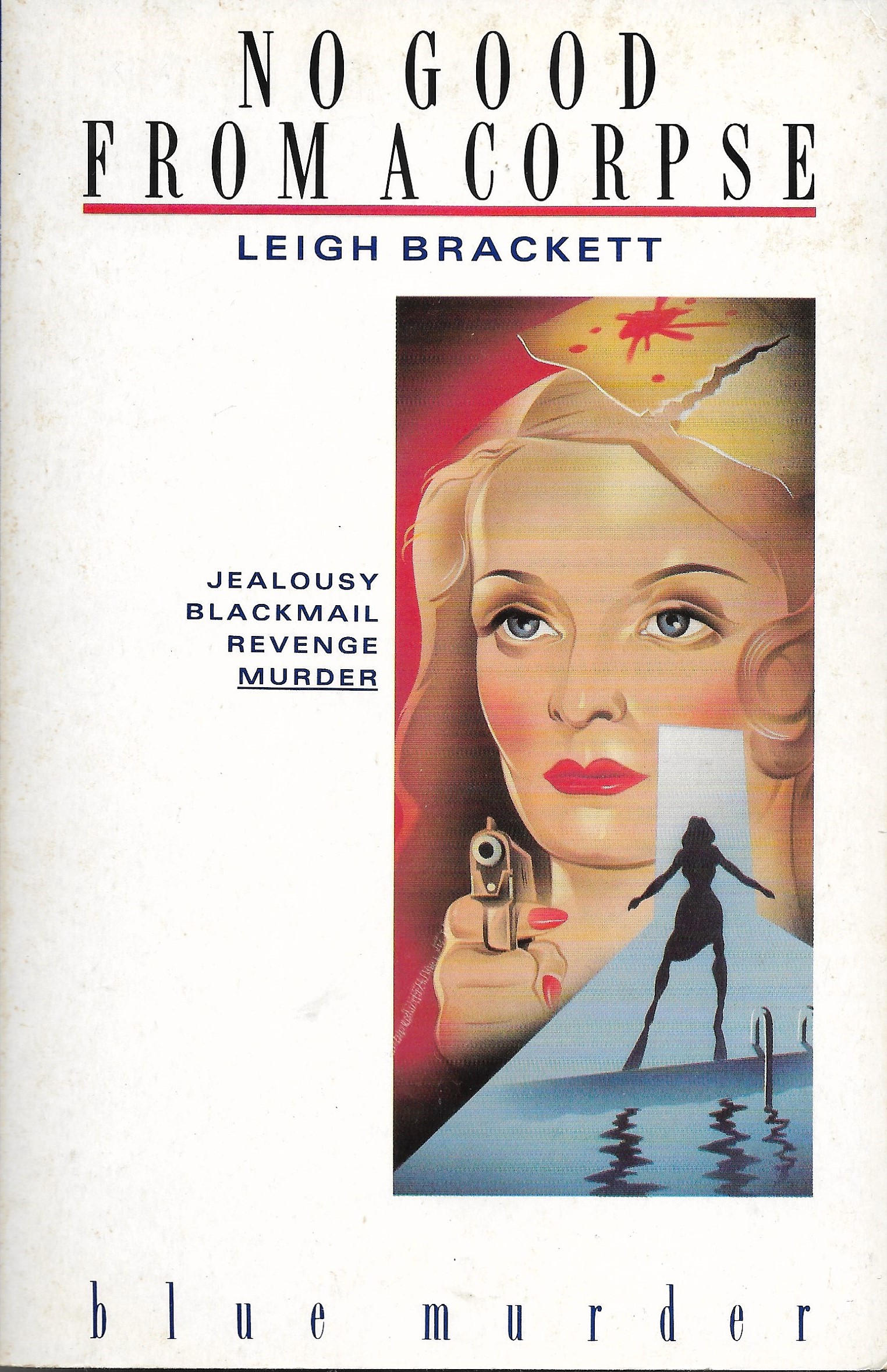

Leigh Brackett (1915-1978), who wrote mainly science fiction, but also westerns and screenplays (delivering a first draft screenplay of The Empire Strikes Back just before her death), but only a couple of crime thrillers. On the strength of her first, the hardboiled private eye tale No Good From A Corpse in 1944, she was hired to work on the screenplay of the film of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep; and you can see why.

This is classic Hollywood noir where crimes are solved (or committed) by private detectives and the police are there merely to help them, tactfully ignoring the mayhem their investigations cause. Edmund Clive is Brackett’s private eye hero, returning to Los Angeles from a case in San Francisco and into the arms of his true love, night club singer Laurel Dane. In short order Clive takes on a case for the rich, dysfunctional Alcott family but before he has time to light another cigarette or take a slug of whiskey, girlfriend Laurel is murdered by a savage blow to the head. She is only the first case of head trauma: Clive gets knocked out several times (also shot and hit by a moving car), as do others and another female dies this way.

This is classic Hollywood noir where crimes are solved (or committed) by private detectives and the police are there merely to help them, tactfully ignoring the mayhem their investigations cause. Edmund Clive is Brackett’s private eye hero, returning to Los Angeles from a case in San Francisco and into the arms of his true love, night club singer Laurel Dane. In short order Clive takes on a case for the rich, dysfunctional Alcott family but before he has time to light another cigarette or take a slug of whiskey, girlfriend Laurel is murdered by a savage blow to the head. She is only the first case of head trauma: Clive gets knocked out several times (also shot and hit by a moving car), as do others and another female dies this way.

But our hero is a tough guy - and his toughness extends to casually slapping females who irritate him and they, worryingly, seem to accept this - and survives to provide a final twenty-page explanation of the plot. Interestingly it is quite late on in the book before we get any indication that there is a war on (it is 1944 and word would surely have reached Los Angeles by now) when Clive tells a housemaid, clearly smitten if not yet slapped by him, that she “would look cute in overalls, riveting” and that he wouldn’t object if she got back at her employer by sneaking “all her girdles into the rubber drive”. Both references may well be lost on the younger reader.

Enjoy 2025 if you can,

The Ripster.