|

RIPSTER REVIVALS #16

An irritatingly frequent ‘occasional’ column of ramblings around the world of (mostly)crime fiction and thrillers which begs the question: what’s the difference between Ripster Revivals and the Getting Away With Murder column he used to churn out? {Answer: there is none.]

|

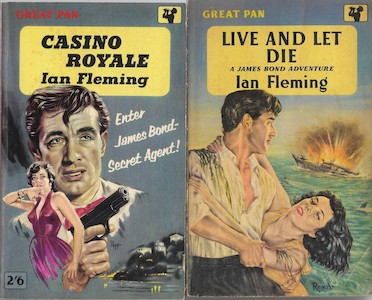

Is the name still Bond?

I was asked recently, by a distinguished colleague who fancied reading some ‘unadulterated Fleming’, if I knew when the James Bond books had been ‘edited’ to remove references to things which might offend the delicate sensibilities of the younger generation. I was aware that some form of sanitisation had been proposed but I had not followed its progress. I could only recommend that my colleague stick to the early paperback editions which I have owned for many years.

I can confirm that these editions do not come with what are called Trigger Warnings, but thinking about it, Trigger Warning wouldn’t be a bad title for the next James Bond film...

Up From Down Under

It was a pleasure to catch up with veteran Australian crime fiction reviewer the globe-trotting Jeff Popple on a flying visit to London. Having set the worlds of crime fiction (both hemispheres) to right we moved on to a detailed debate on the quality of Reisling available in darkest Soho. I could not possibly say which discussion lasted the longest.

It was a pleasure to catch up with veteran Australian crime fiction reviewer the globe-trotting Jeff Popple on a flying visit to London. Having set the worlds of crime fiction (both hemispheres) to right we moved on to a detailed debate on the quality of Reisling available in darkest Soho. I could not possibly say which discussion lasted the longest.

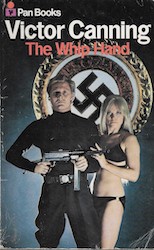

Although distance means that Jeff and I get together far too rarely, he knows my tastes well, particularly my fondness for garish paperback thrillers from the 1960s and he presented me with a famous (or infamous) Pan edition of Victor Canning’s 1965 thriller The Whip Hand which I remember reading and enjoying back in the days when such a cover – wrong in so many ways – would not have caused a raised eyebrow.

Being far more up to date than I am, Jeff also brought me an advance proof of a new novel by the distinguished Aussie journalist Michael Brissenden, Dust, to be published by Affirm Press in September. I think Dust is an example of what is known as ‘Outback Noir’ and all I can say is that if it is, it is a prime example because it is very, very good. Sadly, I cannot find any details of a UK publication date. I hope that is an oversight on my part and not the lack of initiative by British publishers.

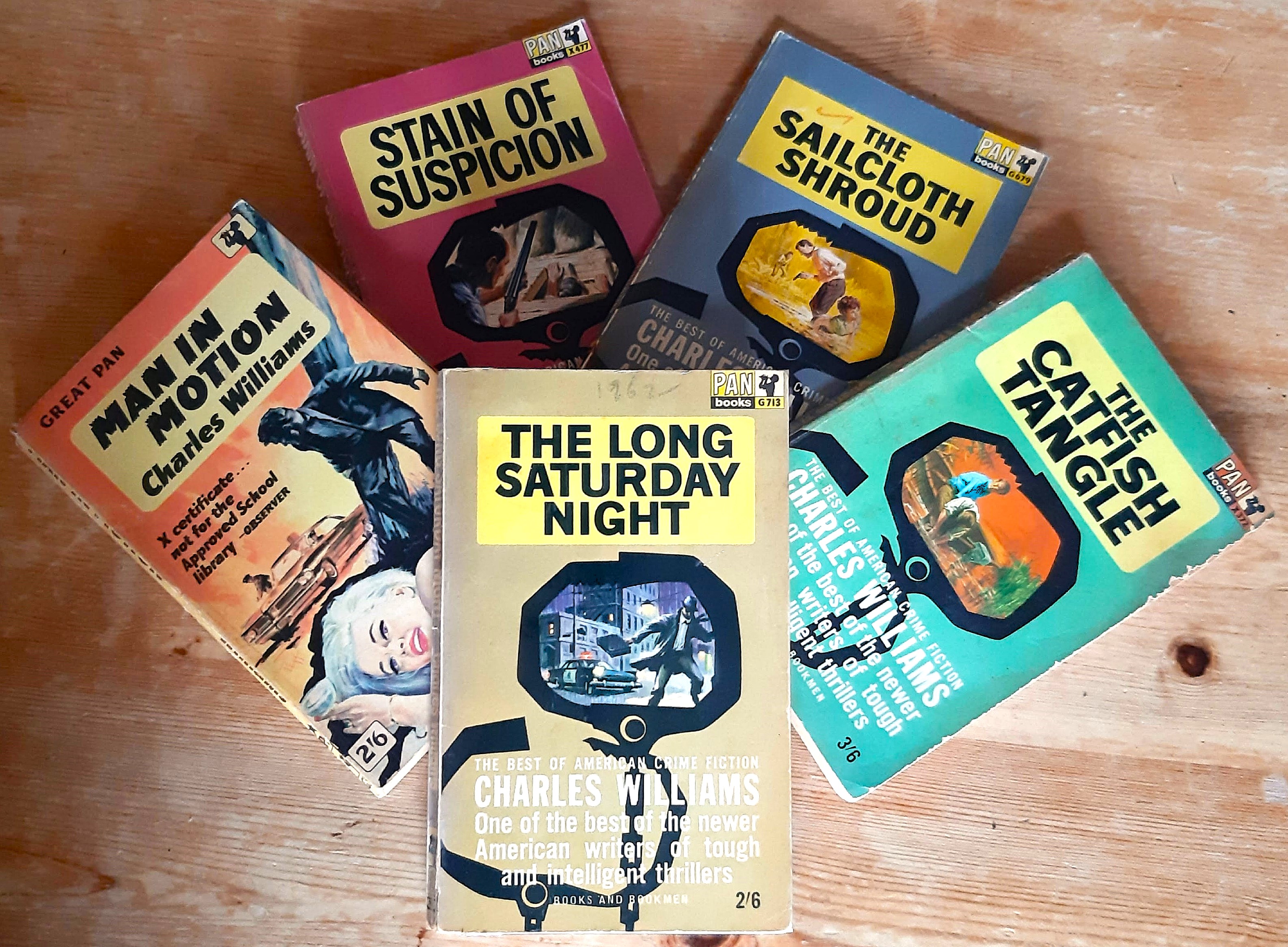

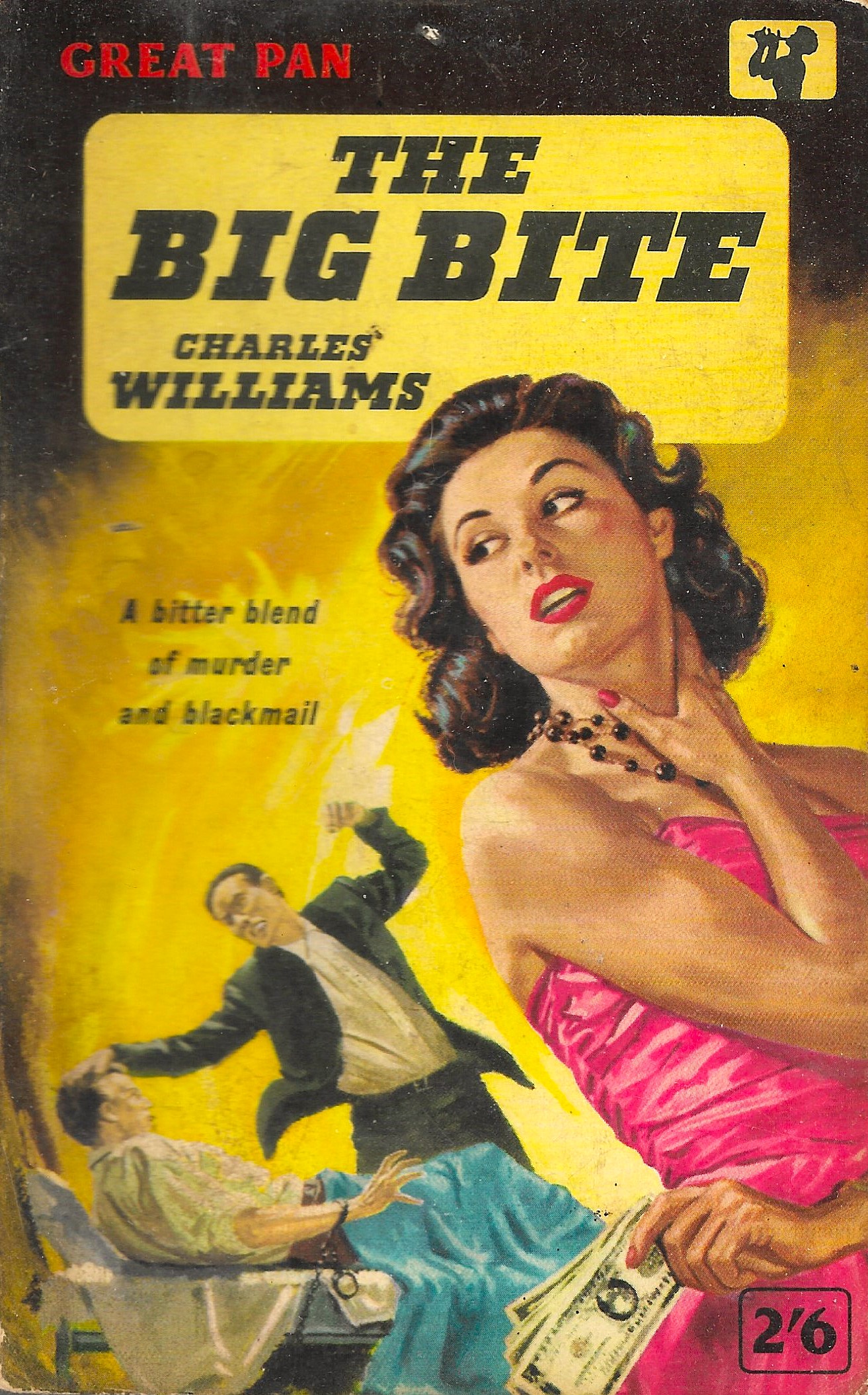

Chas Williams

I got into Charles Williams through films of two of his books which came out in quick succession in 1989 and 1990: Dead Calm and The Hot Spot, Dennis Hopper’s adaptation of the novel Hell Hath No Fury. Initially, I was more impressed with Dead Calm and the other Williams thrillers involving boats, coastal settings and murderousness on the high seas (Williams had been a radio operator in the American merchant marine) such as Aground and Scorpion Reef, which had recently come back into print thanks to No Exit Press and Maxim Jakubowski’s Blue Murder imprint for Xanadu.

Gradually, however, I discovered his more land-based crime novels and realised that he must have been something of a force to be reckoned with most of his novels being published in the UK as Pan paperbacks in the 1960s, seemingly with some commercial success and great acclaim from British reviewers, the Spectator describing his books as ‘Brilliantly composed plot; vivid phrase-making; pace; action and surprise.’ I became hooked and yet could never understand how Williams had so easily slipped from memory despite a mini-revival around the Dead Calm and Hot Spot films and I thought I had acquired and read most of his output.

And then, joy of joy, I discovered (thanks to my bespoke book dealer) that there was a Williams thriller I had not read. Originally titled (I think) Operator when published in the US in 1957, it was issued as a Great Pan paperback in 1960 as The Big Bite and it holds up incredibly well more than sixty years on as a suspenseful, twisty tale of murder and blackmail – one of the twists being when an amateur blackmailer falls foul of the femme fatale (and her ferocious boyfriend) he is blackmailing and finds himself outsmarted and the victim of even more vicious blackmail. It is a great example of noir crime fiction in that from the start you know this isn’t going to end well for the main protagonist, but he has been badly treated and you sort of want to root for him, until you realise his motives are just as venal as the people he goes up against. In the end nobody wins – or do they?

Oddly enough – and fresh from my To-Be-Read pile – the last novel by that American master of dark,

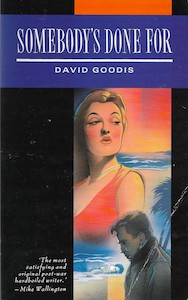

Oddly enough – and fresh from my To-Be-Read pile – the last novel by that American master of dark, dark noir David Goodis (1917-1967), Somebody’s Done For begins in a way one of Charles Williams’ watery offshore thrillers might have.

dark noir David Goodis (1917-1967), Somebody’s Done For begins in a way one of Charles Williams’ watery offshore thrillers might have.

A shipwrecked man is swimming in the sea, alone and out-of-sight of land and he’s almost done for, disorientated and exhausted. A rowing boat with two men appear and rescue seems at hand, but the men in the boat look at the swimming man then row away leaving him to drown. But of course he doesn’t, instead he washes upon a swampy shore where he is ‘rescued’ by the mysterious Vera who leads him to a refuge in the swamp which turns out to be anything but a safe haven and our swimming man’s troubles are only just starting.

Coincidentally, like some Charles Williams titles, this 1967 David Goodis thriller was reissued in Maxim Jakubowski’s Blue Murder series for Xanadu books, a splendid imprint which also revived great hard-boiled fiction by Kenneth Fearing, Jim Thompson, Jonathan Latimer and Cornell Woolrich, which is quite a line up.

Outrageous Spies

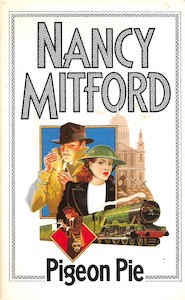

Inspired by the excellent television series Outrageous about the Mitford sisters, I sought out Pigeon Pie, the light-hearted spy thriller by Nancy Mitford which, she admitted, was ‘not well received when first published’. Perhaps that isn’t surprising as the book was written before Christmas 1939 and published on 6th May 1940, four days before the German army invaded France and the Low Countries.

It is, of course, not so much a thriller as a satire on the attitudes of the upper classes, stupid men and frothy debutantes who actually compete with each other to be the most exotic female spies in London (taking inspiration from The Thirty-Nine Steps) whilst doing serious war work in Air Raid shelters and make-shift hospitals devoid of real patients as the Blitz was yet to happen. The most overwhelming fear being that of German parachutists descending ‘Dracula-like’ in the night. Central to the zany plot – which involves an ageing opera singer and national treasure broadcasting subversive songs on behalf of the Nazis, a kidnapped bulldog and a plot to blow up London’s drains – is Lady Sophia Garfield and her circle of dotty aristocratic friends and rivals. Given that Lady Sophia is a thinly-disguised Nancy Mitford, and Nancy Mitford being Nancy Mitford, there are some good jokes and an especially nice poke at her earlier novel which satirised her own family’s Fascist sympathies.

It is, of course, not so much a thriller as a satire on the attitudes of the upper classes, stupid men and frothy debutantes who actually compete with each other to be the most exotic female spies in London (taking inspiration from The Thirty-Nine Steps) whilst doing serious war work in Air Raid shelters and make-shift hospitals devoid of real patients as the Blitz was yet to happen. The most overwhelming fear being that of German parachutists descending ‘Dracula-like’ in the night. Central to the zany plot – which involves an ageing opera singer and national treasure broadcasting subversive songs on behalf of the Nazis, a kidnapped bulldog and a plot to blow up London’s drains – is Lady Sophia Garfield and her circle of dotty aristocratic friends and rivals. Given that Lady Sophia is a thinly-disguised Nancy Mitford, and Nancy Mitford being Nancy Mitford, there are some good jokes and an especially nice poke at her earlier novel which satirised her own family’s Fascist sympathies.

I think the book was simply too ridiculous a thriller for the prevailing mood of the reading public (it was competing with Eric Ambler’s Journey into Fear) with agents blinking messages in Morse Code, secret instructions written on handkerchiefs and on breakfast boiled eggs, not to mention Nazi parachutists, when they come, being instantly captured by ARP wardens and Boy Scouts who bind their legs with twine just as they come in to land!

I did, however, learn a new word: gyves, a medieval term for fetters (or leg-irons) which are used to restrain those pesky Fallschirmjäger and it was interesting to see in full the phrase ‘he’s on the water waggon’ for someone who is off the booze. Not something you often read these days.

To Russia (and other places) With Love

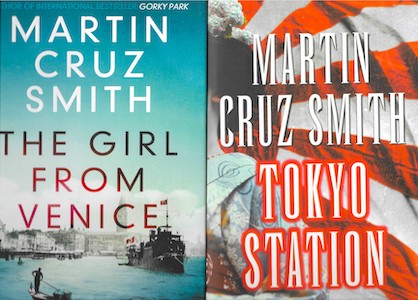

Martin Cruz Smith, who died last month aged 82, will always be celebrated, and quite rightly too, for his excellent thrillers featuring Russian investigator Arkady Renko, and I have been a fan since his debut in Gorky Park in 1981.

Splendid though the Renko books are (and Polar Star is on my To-Be-Re-Read Pile), I would like to give a shout-out to two personal favourites among Smith’s non-Renko work. The Girl From Venice from 2016 is an evocative portrait of Venice at the fag-end of WWII and the plight of a young Jewish girl on the run from die-hard Nazis who is sheltered by local fishermen and partisans who are in constant danger of betrayal to the remnants of Mussolini’s fascist regime. At the other end of the war, Tokyo Station, published in 2002 (and called December 6 in the US), tells of Harry Stiles, an American brought up in Japan and far too familiar with the Tokyo underworld, who finds himself suspected of being a spy on the eve of the attack on Pearl Harbour

Parisienne Walkways

When I was young, impressionable, and just starting out as a crime writer, I was intrigued by a character who seemed to hover on the edges of the Crime Writers’ Association and the Detection Club, who would appear wearing a brown bowler hat or a monocle or cloak which might have been a Dracula cast-off, sometimes all three. His name was John Kennedy Melling and he described himself as a journalist, a theatre historian, a showbiz accountant and a ‘self-confessed dilettante’. Although he did not write crime fiction himself, he had authored a book, Murder Done To Death, about parody and pastiche in crime novels, wrote regularly for a magazine called Crime Time and he seemed almost obsessed with the work of two crime writers in particular:  Gwendoline Butler (1922-2013) and Georges Simenon, whom he claimed to have known and who he called “Master”. On several occasions, I was treated to long and rambling reminiscences by JKM (as he was known) of conversations the two had supposedly had – perhaps they did – which involved lots of ‘But Master, you must admit...’ ‘Tell me, Master...’ ‘But you are the master, Master...’ and so forth. As a result, I am afraid to say that Mr Melling put me off reading Georges Simenon for several years.

Gwendoline Butler (1922-2013) and Georges Simenon, whom he claimed to have known and who he called “Master”. On several occasions, I was treated to long and rambling reminiscences by JKM (as he was known) of conversations the two had supposedly had – perhaps they did – which involved lots of ‘But Master, you must admit...’ ‘Tell me, Master...’ ‘But you are the master, Master...’ and so forth. As a result, I am afraid to say that Mr Melling put me off reading Georges Simenon for several years.

I am sure JKM (who died in 2018 aged 91) would be horrified to hear me say that nowadays I read a Simenon ‘Maigret’ in order to relax between reading books which require me to make a more serious effort. This is not meant to be disparaging in any way, rather that I find the cases of Inspector Jules Maigret to be effortless reading and, in a way, comforting for their familiarity: the pipe smoking, the beer drinking, the backstreets of Paris, the meals in brasseries or at home cooked by Madame Maigret. And there is always the knowledge that Maigret will usually solve the crime at hand by understanding the psychology of the perpetrator rather than via a car chase or a gun fight.

Which is exactly what he does in Maigret Sets A Trap from 1955 when faced with the vicious, seemingly random, murders of five women by a maniac who may be Paris’ very own Jack the Ripper. After a massive police operation to flush out the killer, Maigret follows (literally) a slim thread of evidence but the case only concludes after a tense psychological stand-off engineered by the clever and incredibly patient Inspector.

New Stuff

I am indebted, yet again, to that bold and big-hearted bunch at Brash Books in the U.S. of A. for introducing me to the work of comic novelist Tim Sandlin, an author who chronicles, with a far from lazy eye and a wicked sense of humour, the daily absurdities of life in the community of ‘GroVont’ in the backwaters of Wyoming. Published by Brash Books in December, Lit revolves around writing and books and so, naturally, opens with at a traditional Wyoming book burning! The open line reminded me of a famous James Crumley opening, or perhaps of a drunk Garrison Keillor channelling James Crumley: The first time I had what could be called dealings with Judge Joubert, he was in a push-and-shove fight with the Pollard sisters at a book burning in the parking lot of the GroVont library. From then on I was hooked.

Having noted the passing of the creator of Russian detective Arkady Renko, a new Soviet-era detective bursts into print. Anton Markovich Belkin is an official investigator in Moscow in 1934, albeit a minor one and one determined to keep his head down when a lot of his contemporaries are losing theirs in a Soviet state still finding its feet. Despite, or perhaps because of, his experiences in the civil war, Belkin retains his faith in Bolshevism, though he is well aware of the corruption and crime it has enabled within Stalin’s brutal regime which is busy constructing the Moscow metro system as a triumphal example of socialism in action. Tunnelling under ancient Moscow in truly awful conditions, buried treasures from previous ages, including the first Tsars, are discovered. So too is the murdered body of a distinguished archaeologist and Belkin is reluctantly drawn into the investigation. A little slow to get going as a thriller, Moscow Underground by Catherine Merridale, an academic specialising in Russian history, brilliantly evokes the doubts, suspicions and cruelties of the period as should be out now from William Collins.

I am keenly awaiting the publication in late September of Smoke In Berlin [Hemlock Press] by Oriana Ramunno, an Italian who lives in Berlin, as it features her war time detective Hugo Fischer who made his traumatic debut in Ashes in the Snow two years ago. Fans of the Martin Bora books by Ben Pastor (another Italian) and Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther should put this one on their radar.

Coming in October is an unsettling example of ‘Bush Noir’ - if such a thing exists - in a debut novel by Zoë Rankin, The Vanishing Place [Viper]. The ‘bush’ in question is the isolated west coast of New Zealand’s South Island and a harsh and lonely place it seems to be. Our narrator, Effie, escaped from a drastic home life in the area as a young girl but now is drawn back there when another girl staggers out of the bush, blood-stained and traumatised, displaying suspiciously similar genetic features. This is an unsettling story of innocent children badly treated, told with empathy and great skill and overall, quite riveting.

Before then, at the end of September I will be enjoying the new Felix Francis thriller Dark Horse [Zaffre] where the protagonist is, I believe, a female jockey. The novel also features Sid Halley, one of my favourite characters from the Francis stable.

And though it arrived too late for me to give it a full review here, I am enjoying the latest DCI Christine Caplan novel by Tartan Noirista Caro Ramsay, Where She Lies [now out from Severn House]. In Caplan’s fourth case – despite on-going battles with her family and the roads of west Scotland – the detective enters the cultish world of ‘the influencer’ and a generation which has just discovered the advantages of being a ‘nepo baby’. (Not that we had such a thing in my day, one just relied on one’s Godfather...) When a prominent lifestyle guru goes off the parapets of a coastal castle and smashes into the rocky shore below the act and the corpse have to look perfect for the inevitable Instagram pics because image is all. Thank goodness the pragmatic, not-to-be-influenced Caplan is on the case.

Odds and Probably Sods

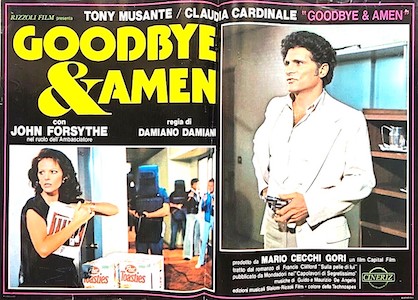

I can’t think how I found out, but it was a surprise to learn that a vintage thriller I have always had a soft spot for had been made into a film in 1977 in Italy. The novel in question being Francis Clifford’s The Grosvenor Square Goodbye which won the CWA’s 1974 Silver Dagger and which I was honoured to bring back into print as a Top Notch Thriller in 2010.

Few of Clifford’s novels were filmed in English for some reason (I can think of two), which is sad given the strength of his stories and the quality of his writing and I had no idea that the Italians had adapted (with Rome standing in for London’s West End) this one as Goodbye & Amen.

I am told it is available to view (in Italian) on something called YouTube and I intend to investigate.

From the Clubhouse

For reasons I cannot begin to comprehend, when Steve Jones’ thriller Terminally Kill appears as a Penguin paperback on 4th September, it will be called The Last Laugh Club.

I have no idea what could possibly have prompted this change of title by publisher Michael Joseph but if it reflects a popular trend then I am very happy to consider changing the name of this column to The Getting Away With Murder Club.

Toodles!

The Ripster.