It is one of the torments of writing about Northern Ireland politics that to understand the state of mind of those you are commenting on, you have to read an inordinate amount of ill-informed or ill-intentioned drivel. Fiction can be particularly painful, not least because so much of it has been predicated on the lazy myth that Catholics are romantic freedom fighters, Protestants oppressive bigots and the British wily and treacherous. Worse again, there are an alarming number of republicans who fancy themselves as writers but are in fact merely propagandists, and mawkish propagandists at that.

And then there are Troubles thrillers - around 400 of them so far. Yes, they include some fine books. When Gerald Seymour wrote Harry’s Game (1977), he had been a war correspondent for more than a decade, he knew Northern Ireland and he understood terrorism; his story about an undercover agent charged with finding the IRA assassin of the prime minister deserved to become the mega-seller it did. The Omagh-born Benedict Kiely’s Proxopera (1977) tells of a school-teacher ordered by IRA neighbours to drive a bomb to the house of a judge he admires or have his family killed: along the way we learn much about how apparently decent people can become sectarian murderers. In Divorcing Jack (1994), the Northern Ireland journalist Colin Bateman brilliantly lampooned the tribal thugs and hypocrites from all sides who have driven the violence. (Sorry for the blatant self-promotion, but I got a lot out of my system when I wroteThe Anglo-Irish Murders, which was a deserved satire on the peace process which heaped contumely on the British and Irish governments and their officials, Irish-America and loyalist and republican paramilitaries alike.)

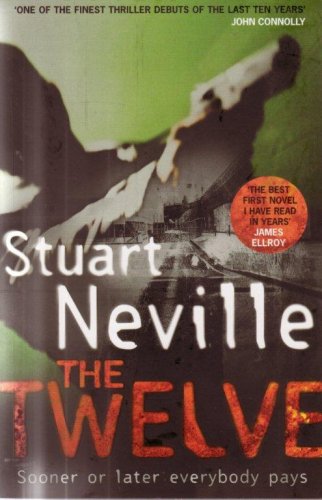

Still, most of the thrillers were what has rightly been christened ‘Troubles Trash’, which is why people who understand Northern Ireland have fallen on Stuart Neville’s The Twelve (in the US it is published as The Ghosts of Belfast) with shrieks of joy. His publisher sent it to me in manuscript form in the spring, asking if I’d have a skim and point out anything that jarred. I sat down one Saturday morning and was unable to stand up until four hours later when finally, heart in mouth, I reached the end. Nothing had jarred: like James Ellroy, John Connolly, Ken Bruen and others, I reached for the superlatives in my encomium.

I’m squeamish - though much less so than before I wrote a book which required me to read four volumes of inquest reports on 31 dead bodies (Aftermath: the Omagh bombing and the families’ pursuit of justice) - and I avoid novels containing graphic violence. I also never read anything about ghosts. So why am I an evangelist for a harrowing book about Gerry Fegan, a former IRA killer who is haunted by twelve people he killed - three British soldiers, two loyalist paramilitaries, a policeman, two members of the Ulster Defence Regiment, the boy tortured to death for giving information to the cops, and the butcher, the woman and the child blown up in a shop by Fegan’s bomb - and who sets about avenging the ghosts by murdering those they hold ultimately responsible for their deaths?

While The Twelve is taut and beautifully-written, it is not its success as a thriller that so impressed me. It is that it that after decades of painfully seeking to achieve an understanding of what went on during the Troubles, I am stunned to find a novel that reflects the extraordinary complexity of that period, that treats the various players without sentimentality but with deep understanding, and has empathy for the unfortunates caught up in something beyond their ability to control. The blurb provided by my friend Sean O’Callaghan, whose The Informer described how he became caught up in the IRA as a teenager and later atoned for his crimes by becoming an unpaid agent of the Irish police, says simply: ‘Stuart Neville goes to the heart of the perversity of paramilitarism’. And so he does, in his unflinching depiction of how idealists and ideologues who see themselves as community defenders can turn into brutal, hypocritic persecutors of their own people as well as their traditional enemies. But he also goes to the heart of the murkiness of elements of counter-intelligence, the cynicism and narrow self-interest of some of our rulers, the rotten apples that can be found in an honourable police force, the supine nature of fellow-travellers, the moral ambivalence to be found among some clergy and much else.

For readers that know Northern Ireland, there is much fun to be had in discussing where he got his inspiration for this or that frightful character. But no one should be put off because the action is set in a small province of the United Kingdom. The themes Stuart Neville is addressing are among the greatest in literature: in his treatment of crime, cruelty, guilt, punishment, suffering and justice it is impossible not to be reminded of Dostoevsky.

There is no white-washing of Fegan, who has truly done terrible things, and yet such is the power of the characterisation that it is impossible not to sympathise with him on his murderous mission. And as someone implacably opposed to the death penalty, and who has spent nine years helping victims of terrorism to find justice through the legal system, it is alarming to find myself drawn into a primitive reaction of cheering the killer on. Like the best fiction, The Twelveforces one is forced to confront one’s own frustrations and hidden demons.

In time-honoured fashion, Stuart Neville has knocked around a bit: he has, he tells us, ‘been a musician, a composer, a teacher, a salesman, a film extra, a baker and a hand double for a well known Irish comedian, and now I'm currently a partner in a successful multimedia design business in the wilds of Northern Ireland.’ Yet while such experience is of great help in writing realistically, it is his imagination, his intelligence and his empathy that lifts this book from the ranks of good thriller to astounding novel. He is collecting marvellous reviews. If you don’t take my word for why you should read him, have a look atwww.stuartneville.com and be convinced.

Ruth recently published: Aftermath: the Omagh bombing and the families' pursuit of justice Visit her website: www.ruthdudleyedwards.comwhere can i get the abortion pill online

online buy abortion pills online

online

online what to do when husband cheats

spyware apps for android

link cell spy monitoring software

my wife cheated on me now what do i do

link your wife cheated on you

viagra manufacturer coupon

go drug coupon

discount coupons for cialis

site cialis discounts coupons

discount coupons for cialis

go prescription coupon card

ventolin prospecto

click ventolini cali

early abortion pill

acnc.com abortion pill

withdrawal from naltrexone

click naltrexone pharmacy

where can i buy low dose naltrexone

link naltrexone uses