Robert Littell is a bestselling American novelist and journalist who specializes in spy novels concerning the CIA and the Soviet Union. He has been awarded the Crime Writer’s Association Gold Dagger and the LA Times Book Prize. His New York Times bestselling novel The Company was adapted into a TV series. He served for four years in the U.S. Navy and is a former Newsweek writer. He currently lives in France.

When Kim Philby fled to Moscow in 1963, he became the most infamous

double agent in British history. A member of the intelligence services since

World War II, he later rose to become ‘our man’ in Washington. The exposure of

other members of the Cambridge Five led to the revelation that Philby had been

working for the KGB for even longer than he had been part of MI6. Yet he

escaped, and spent the last twenty-five years of his life in Moscow.

Young Philby tells the story of this traitor through the eyes of more than twenty characters. As each layer is revealed, the question arises: Who, really, was this man?

Coda: A True Spy Story

Where the Author of Young Philby Explains Why the Idea That Kim Philby Might have been a Double Agent— Or Should That be Triple?—is Not Far- Fetched.

I

spent the winter of 2000 in Jerusalem doing research for a novel set in the

Middle East. One evening I had dinner with my great friend Zev Birger, the head

of the Jerusalem Book Fair at the time. He had been instrumental in introducing

me to then retired prime minister, now president of Israel, Shimon Peres, with

whom I eventually collaborated on a book of conversations. Zev, who was said to

know everyone important in Israel, asked me out of the blue if there was anyone

in the country I wanted to meet that I hadn’t met. I told him that as a matter

of fact there was. It was the long-time mayor of Jerusalem, Teddy Kollek, by

then retired.

The next morning Zev phoned to say he had arranged a

rendezvous. At noon on 31 January 2000 I turned up in Teddy Kollek’s office at

the Jerusalem Foundation on Rivka Street. Mr. Kollek, a heavy man, then

eighty-nine, who smoked thin cigars, waved me to a seat across the desk

from him and asked why I wanted to see him. He regarded me through professorial

half-glasses that had slipped down along his nose. I explained that I was

familiar with his biography: He’d grown up in Vienna and had been active in

Socialist circles there in the early 1930s. I was curious to know if Mr. Kollek

had come across a young Cambridge graduate in Vienna named Kim Philby. Mr.

Kollek said that everyone in the leftist community in Vienna had been

acquainted with Philby in those days, that he himself knew him by sight. I

asked if Mr. Kollek had known Litzi Friedman as well. Yes, he said, he’d known

Litzi well enough to say hello to her; in Vienna, he continued, everyone knew

she was a Communist and many assumed she was some sort of Soviet agent. I asked

if Mr. Kollek was aware that Philby and the Friedman woman had gotten married

in Vienna after the right-wing Chancellor Dollfuss suppressed the Socialists

and Communists in 1934. Again he said yes, it was common knowledge that Philby

had married Litzi to get her a British passport. And then, to my surprise, he added

that it had been widely assumed Litzi Friedman must have recruited Philby as a

Soviet agent.

Unprompted, Mr. Kollek began telling me another story:

When the Jewish state was born in 1948, the Mossad, Israel’s CIA, was eager to

contact the new American Central Intelligence Agency, but the CIA people,

believing that the Mossad could have been infiltrated by Soviet agents posing

as Jewish refugees, kept the Israelis at arm’s length. After repeated requests,

the Americans finally relented and agreed to a first tentative meeting. It was

Teddy Kollek, working for the Mossad, who was dispatched to a certain room in

the Statler Hotel in Washington to make contact. The person representing the

CIA at that initial meeting turned out to be none other than its legendary

counter-intelligence chief, James Jesus Angleton.

A word about James Angleton: Fresh out of Yale

University in the early 1940s, he’d joined the American wartime intelligence

organization, the Office of Strategic Services, and been posted to London to

learn counter-intelligence from His Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. It

was the older and more experienced Kim Philby, a rising star in the SIS, who

took the young American under his wing. The two became fast friends, bunking

together on beds in the SIS building during the German blitz, climbing to the

roof to watch the German bombers raiding London. After the war in Europe ended,

Angleton moved on to direct OSS operations in Italy and when President Truman

created the Central Intelligence Agency in the late 1940s, Angleton became its

counter-intelligence chief.

When Teddy Kollek and Angleton met in the Statler, they

hit it off and became good friends. In Mr. Kollek’s words, they had a close

relationship. Mr. Kollek brought Angleton, whose hobby was growing orchids,

rare Israeli orchids from a farm that belonged to the Rothschilds and dined

with Angleton and his wife, Cicely, at their Washington home. And of course

they regularly collaborated on intelligence matters.

Fast forward to 1952: With the Cold War in full swing,

Mr. Kollek came to Washington to see his friend Angleton at the CIA buildings,

old World War II barracks on the Reflecting Pool. “I was walking towards

Angleton’s office,” Kollek told me when I interviewed him in Jerusalem, “when

suddenly I spotted a familiar face at the other end of the hallway. There was

no mistake about it. I burst into Angleton’s office and said, ‘Jim, you’ll

never guess whom I saw in the hallway. It was Kim Philby!’ And I told him about

Vienna and the marriage to Litzi Friedman and the suspicion that Philby may

have been recruited by her as a Soviet agent.

And I said, ‘Once a Communist, always a Communist.’

”

Startled, I asked Mr. Kollek if those had been his

exact words. “Yes,” he said. “I told him, ‘Once a Communist, always a

Communist.’ ”

I asked if Angleton had reacted. “No, Jim never reacted

to anything. The subject was dropped and never raised again.”

When Mr. Kollek spotted Philby at the end of the

hallway, he was serving in Washington as liaison between the Brits and their

American counterparts at the CIA and FBI. Kim met with his old pal from London,

Jim Angleton, almost daily. The two regularly lunched together at a Georgetown

watering hole on Fridays.

“What happened after you told Angleton about Philby and

Vienna?” I asked.

I have this memory of Mr. Kollek concentrating on the

ash threatening to drop off the end of his cigar. “Your guess is as good as

mine,” he replied.

My guess is at the heart of Young Philby.

In the course of Angleton’s long career, which ended

when he was fired by CIA Director Colby in 1975, the counter-intelligence

chief was obsessed with the possibility of Soviet penetration. CIA employees

who spoke fluent Russian or had Russian or Polish-sounding names fell under a

cloud. Lie detector tests were administered left and right; not everyone

passed. Careers were ruined by Angleton’s shadow of a doubt. Would-be defectors

were turned away for fear they might be Soviet disinformation agents.

Ultimately the CIA’s entire Soviet Russia division was gutted and its

operations against the Soviet Union crippled because of Angleton’s obsession

with Soviet penetration. Whether Angleton learned about Philby’s suspicious

past (Cambridge Socialist Society, Vienna, Litzi Friedman) from Teddy Kollek,

or knew it already, it is unthinkable that he would have permitted Philby to

set foot inside the CIA’s sanctum unless . . .

Unless he had personally turned Philby, or

Philby had been a British agent feeding disinformation to Moscow all along. In

the end, the best way to penetrate the Soviet Heart of Darkness would be to

make Moscow Centre think it had penetrated Western intelligence agencies. At

which point the British and Americans, in the words of my character The Hajj,

could feed the Soviets disinformation until the cows came home.

When Donald Maclean, on the point of being exposed as a

Soviet agent, fled to Moscow (along with Guy Burgess, who apparently lost his

nerve at the last moment and went with him), Kim Philby’s cover was blown.

Forced by SIS to resign in July of 1951, he ended up working as Middle East

correspondent for two London newspapers, The Observer and The

Economist, in Beirut. After he, in turn, fled to the Soviet Union in

1963, Angleton let drop hints to his CIA colleagues that there was more to the

Philby story than met the eye. The suggestion was obviously self-serving. But

was there more?

Teddy Kollek died on 2 January 2007.

The mystery of Philby’s ultimate loyalty lives on.

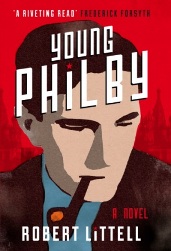

Young Philby By Robert Littell

Published 8th November 2012 £16.99 HBK, Duckworth Publishers

Main Photo © Paris Match

spyware apps for android

link cell spy monitoring software

letter to husband who cheated

femchoice.org why men cheat on beautiful women

i told my husband i cheated

read i want my husband to cheat

free pharmacy discount card

open walgreens in store coupons

coupons prescriptions

site prescription coupon card

discount prescriptions coupons

site discount card for prescription drugs

naprosyn 750 mg

open naprosyn jel nedir

ventolin prospecto

open ventolini cali

prescription discount coupons

abcomke.sk discount coupon for cialis

how long does naltrexone work

link injection for alcohol craving