It used to be that the weather forecast might say

that there was a storm coming our way. Now every storm gets its own name. I

hope we don’t get to a stage where there is a warning about ‘Drizzle Darren’

getting people wet and generating slip hazards.

There is a serious point here. Naming a storm may

make it easier to talk about, but it increases the storm’s perceived impact.

There is an implied threat of greater damage and this generates worry. Words like disaster and crisis are

common place in the news and from our politicians. They think that if they

scare us enough, then we will conform. Warnings and scare

stories generate fear. Fear is designed to provoke an inability to act

independently, which leads to a passive, controlled society.

Our

motorways show how the government thinks. Are they spending money to educate

drivers on road safety or installing miles of ‘smart’ motorways that adjust the

speed limit to slow traffic down if there is some congestion? They don’t trust

drivers to act for themselves, so they control. Compulsory vaccination anyone?

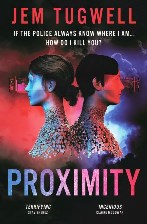

Proximity takes these trends and exaggerates

them, slightly, so that we live in a nanny

state where we are not trusted to make our own decisions.

That’s only

half the story.

When you

look at technology, there is always a particular use it is designed for. The

smart phone, for example, was designed to allow mobile calls and for you to

communicate with the world. However, there is an unintended consequence. Look

around any restaurant and you can see people sitting opposite each other and

not communicating. They are glued to their phones and ignoring each other.

Social media was meant to bring people together, but it generates storms of

abuse when someone says something that others object to - and there’s no

shortage of people being offended by every point of view.

We already have company employees with embedded ID chips.

They give the great convenience of no passwords and no keys to lose or forget.

Sound goods. They should help prevent identity theft. Fitbits and other health

tracking devices should improve health. Excellent. What could go wrong?

If you do a quick count of the possible things an

identity chip could replace, there are loads. Every credit card, tickets for

travel and events, your passport, driving licence, car keys, house and office

keys, every website login. The list goes on and on. Would you really want a

separate embedded chip for every possible use? One centralised chip makes much

more logical sense. Then who runs it? The government would seem more secure

than a company, but what else might they use it for?

When you mix technology and political will, you get

the world of Proximity. The technology in the book was designed to provide the

ultimate in convenience. Then the government used it to track where you are all

the time. This you can argue is an invasion of privacy, but it gives a way to

solve a lot of crime. You know exactly who was at the scene of every murder, abuse,

stabbing, burglary, etc. There’s no hiding. The loss of civil liberty is deemed

worth the cost. Or would you argue that a preventable stabbing is a fair

exchange for your privacy on your morning commute?

The centralised health tracking in Proximity

allows for pre-emptive diagnosis and early detection of illness. Great.

However, as with initiatives like the sugar tax, when the government decides

you are not going to change on your own, they can make the change for you. They

can control your calorie and alcohol intake. You’ll be fitter and healthier. They

can tax your consumption. What’s the problem if you can’t eat that bit of

chocolate?

Like now, Proximity’s world has positives

and negatives, but which is which? The parts I like might scare you. It’s

interesting to see different peoples boundaries and moral dilemmas.

Proximity

is a fast-paced crime thriller, but set in a near-future world where, “You

can’t get away with anything. Least of all murder.”

When you give technology to governments, what could

possibly go wrong?

Proximity

(Serpentine Books) is available in paperback, ebook and audio on the 6th June

2019.

Read Gwen Moffat's review here